Guy Burgess facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

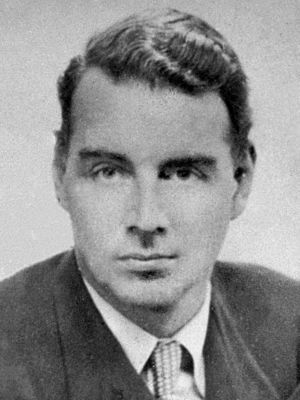

Guy Burgess

|

|

|---|---|

Photo portrait, before 1951

|

|

| Born | 16 April 1911 Devonport, Devon, England

|

| Died | 30 August 1963 (aged 52) Moscow, Soviet Union

|

| Other names | Codenames "Mädchen", "Hicks" |

| Known for | Member of "Cambridge Five" spy ring; defected to Soviet Union 1951 |

Guy Francis de Moncy Burgess (born April 16, 1911 – died August 30, 1963) was a British diplomat and a secret agent for the Soviet Union. He was part of a group known as the Cambridge Five spy ring. This group worked secretly from the mid-1930s until the early years of the Cold War.

In 1951, Burgess moved to the Soviet Union with another spy, Donald Maclean. This event caused big problems for the intelligence sharing between Britain and the United States. It also created a lot of trouble and low morale within Britain's foreign and diplomatic services for a long time.

Guy Burgess came from a middle-class family. He went to famous schools like Eton College and Trinity College, Cambridge. At Cambridge, he became interested in left-wing politics and joined the British Communist Party. In 1935, Soviet intelligence recruited him. This happened because Harold "Kim" Philby, who later became a double-agent, suggested him.

After leaving Cambridge, Burgess worked for the BBC as a producer. For a short time, he also worked as a full-time intelligence officer for MI6. Then, in 1944, he joined the Foreign Office.

At the Foreign Office, Burgess worked as a private secretary for Hector McNeil. McNeil was the deputy to Ernest Bevin, who was the Foreign Secretary. This job gave Burgess access to many secret documents about Britain's foreign policy after 1945. It is thought that he gave thousands of these documents to his Soviet contacts. In 1950, he became the second secretary at the British Embassy in Washington. He was sent home from this job because of repeated problems with his conduct. Even though he was not suspected of being a spy at this time, Burgess went with Maclean when Maclean had to flee to Moscow in May 1951 because he was about to be caught.

No one in the West knew where Burgess was until 1956. Then, he appeared with Maclean at a short press conference in Moscow. He said his reason for leaving was to help improve relations between the Soviet Union and the West. He never left the Soviet Union. Friends and journalists from Britain often visited him. Most of them said he lived a lonely life. He never regretted his actions and did not believe his activities were treason. He had enough money and things he needed, but his health got worse due to his habits. He died in 1963.

Experts find it hard to know how much damage Burgess's spying caused. However, they believe that the problems he caused in relations between Britain and America were perhaps more helpful to the Soviets than any secret information he provided. Guy Burgess's life has often been used in books and plays. Famous examples include the 1981 play Another Country by Julian Mitchell and its 1984 film version.

Burgess also told the Soviets about the Information Research Department (IRD). This was a secret part of the Foreign Office. It dealt with Cold War and pro-colonial propaganda. However, Burgess was quickly fired from the IRD for breaking rules.

Contents

Life Story

Early Years and School

The Burgess family's history in England goes back to 1592. That's when Abraham de Bourgeous de Chantilly came to Britain. He was a refugee from religious troubles in France. The family settled in Kent and became wealthy, mostly as bankers. Later, some family members joined the military. Guy Burgess's grandfather, Henry Miles Burgess, was an officer in the Royal Artillery. He served mostly in the Middle East.

His youngest son, Malcolm Kingsford de Moncy Burgess, was born in Aden in 1881. Malcolm had a regular career in the Royal Navy. He eventually became a commander. In 1907, he married Evelyn Gillman, whose father was a rich banker from Portsmouth. The couple lived in Devonport. Their first son, Guy Francis de Moncy, was born there on April 16, 1911. His brother, Nigel, was born two years later.

The Gillman family's wealth made sure Guy's home life was comfortable. Guy probably had a governess for his first schooling. At age nine, he became a boarder at Lockers Park School. This was a private preparatory school near Hemel Hempstead. He did well there, getting good grades and playing for the school's football team. He finished the Lockers curriculum a year early. He was too young to go straight to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth. Instead, he spent a year at Eton College starting in January 1924.

After his father retired from the navy, the family moved to West Meon in Hampshire. On September 15, 1924, Malcolm died suddenly from a heart attack. Despite this sad event, Guy's education continued as planned. In January 1925, he started at Dartmouth. At Dartmouth, there were strict rules and a strong focus on order. Burgess did well in this environment, both in his studies and in sports. The college thought he would make an "excellent officer." However, an eye test in 1927 showed a problem. This meant he could not have a career in the navy's main officer branch. Burgess was not interested in other navy jobs, so he left Dartmouth in July 1927 and went back to Eton.

Burgess's second time at Eton, from 1927 to 1930, was mostly good. He did well in his studies and made many friends. He started to build a network of contacts that would be helpful later in his life. People remembered Burgess as lively and a bit unusual because of his left-wing political ideas. In January 1930, he won a history scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge. He finished school with more awards in history and drawing. He always remembered Eton fondly. His biographers said he was never embarrassed about being educated in such a privileged school.

Time at Cambridge University

Student Life

Burgess arrived at Cambridge in October 1930. He quickly got involved in many student activities. Not everyone liked him; some found him self-centered and unreliable. But others thought he was funny and good company. After one term, he joined the Trinity Historical Society. This group was for the brightest students in history. Here, he met Harold ("Kim") Philby and Jim Lees. Lees was a former miner studying on a scholarship. Burgess found his working-class views interesting.

In June 1931, Burgess designed the stage sets for a student play. It was Bernard Shaw's Captain Brassbound's Conversion, with Michael Redgrave as the main actor. Redgrave thought Burgess was "one of the bright stars of the university scene." He had a reputation for being able to do anything.

In 1931, Burgess met Anthony Blunt, who was four years older and a postgraduate student at Trinity. They shared interests in art and became friends. Blunt was a member of an intellectual group called the "Apostles". In 1932, he helped Burgess get elected to this group. This gave Burgess many more chances to meet important people. Being an Apostle was for life, so he met many leading thinkers of the time. These included G. M. Trevelyan, a history professor, the writer E. M. Forster, and the economist John Maynard Keynes.

In the early 1930s, the world's political situation was very unstable. In Britain, the financial crisis of 1931 showed that capitalism had problems. In Germany, the rise of Nazism caused growing worry. These events made people in Cambridge and elsewhere more radical. Burgess's interest in Marxism grew deeper. He had learned about it from friends like Lees. He also heard the historian Maurice Dobb talk about "Communism: a Political and Historical Theory." Another influence was David Guest, who led the Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS). Under Guest's influence, Burgess began studying the works of Marx and Lenin.

In 1932, Burgess earned first-class honours in the first part of his history degree. He was expected to get similar honors the next year. But political activities took up too much of his time. By his final exams in 1933, he was not ready. He fell ill during the exams and could not finish them. The examiners gave him an aegrotat. This is an unclassified degree given to students who deserve honors but cannot finish their exams due to illness.

Postgraduate Studies and Political Action

Even with his disappointing degree, Burgess returned to Cambridge in October 1933. He became a postgraduate student and teaching assistant. His research topic was "Bourgeois Revolution in Seventeenth-Century England." But he spent most of his time on political activism. That winter, he officially joined the British Communist Party. He became part of its group within CUSS.

On November 11, 1933, he joined a large protest against the city's Armistice Day celebrations. The protesters wanted to lay a wreath with a peace message at the Cambridge War Memorial. They succeeded, even with attacks and counter-protests. These included "a hail of pro-war eggs and tomatoes." Next to Burgess was Donald Maclean. Maclean was a language student and an active CUSS member. In February 1934, Burgess, Maclean, and other CUSS members welcomed groups from Tyneside and Tees-side. These groups were part of the National Hunger March as they passed through Cambridge on their way to London.

When not in Cambridge, Burgess often visited Oxford to meet like-minded people. He became friends with Goronwy Rees, a young Fellow at All Souls College. Rees had planned to visit the Soviet Union in the summer of 1934 but couldn't go. Burgess took his place. During this trip in June–July 1934, Burgess met some important people. He might have met Nikolai Bukharin, a former secretary of the Comintern. When he returned, Burgess didn't have much to say. He only mentioned the "appalling" housing but praised the country for having no unemployment.

Becoming a Soviet Agent

When Burgess came back to Cambridge in October 1934, his chances of becoming a college fellow and having an academic career were fading. He stopped his research because he found out that a new book by Basil Willey covered the same topic. He started a new study on the Indian Rebellion of 1857. However, he spent most of his time on politics.

In early 1934, Arnold Deutsch, a long-time Soviet secret agent, arrived in London. He pretended to be doing research at University College, London. Known as "Otto," his job was to recruit the smartest students from Britain's best universities. These students might later hold important positions in British institutions. In June 1934, he recruited Philby. Philby had caught the Soviets' attention earlier that year in Vienna. Philby recommended several of his Cambridge friends to Deutsch. These included Maclean, who was already working in the Foreign Office. He also recommended Burgess, though he had some doubts because Burgess was sometimes unpredictable.

Deutsch thought Burgess was worth the risk. He described him as "an extremely well-educated fellow, with valuable social connections, and the inclinations of an adventurer." Burgess was given the codename "Mädchen," meaning "Girl." Later, it was changed to "Hicks." Burgess then convinced Blunt that working for the Soviets was the best way to fight fascism. A few years later, another Apostle, John Cairncross, was recruited by Burgess and Blunt. This completed the spy ring often called the "Cambridge Five".

Finally, realizing he had no future at Cambridge, Burgess left in April 1935. The Soviet intelligence services wanted Burgess to join British intelligence. To do this, he needed to publicly show that he was no longer a communist. So, he resigned from the Communist Party. He publicly said he was no longer a communist, which surprised his former friends. He then looked for a job. He applied for positions with the Conservative Research Department and Conservative Central Office but was not successful. He also tried to get a teaching job at Eton but was rejected.

In late 1935, Burgess took a temporary job. He became a personal assistant to John Macnamara. Macnamara was a recently elected Conservative Member of Parliament (MP). Macnamara was on the right side of his party. He and Burgess joined the Anglo-German Fellowship. This group promoted friendship with Nazi Germany. This allowed Burgess to hide his political past very well. It also helped him gather important information about Germany's foreign policy plans. Within the Fellowship, Burgess would say that fascism was "the wave of the future." But in other places, like with the Apostles, he was more careful. His work with Macnamara involved several trips to Germany.

In the autumn of 1936, Burgess met Jack Hewit in a bar in The Strand. Hewit was nineteen and wanted to be a dancer in London. Hewit became Burgess's friend and helper for the next fourteen years. He usually lived with Burgess in his London homes. These were Chester Square from 1936 to 1941, Bentinck Street from 1941 to 1947, and New Bond Street from 1947 until 1951.

Working for the BBC and MI6

First Time at the BBC

In July 1936, after two failed attempts, Burgess got a job at the BBC. He became an assistant producer in the Talks Department. His job was to find and interview people for current affairs and cultural shows. He used his many personal contacts and rarely faced rejection. His relationships at the BBC were difficult. He argued with managers about his pay. Colleagues found him annoying because he was opportunistic and messy. One colleague remembered him as "a snob and a slob."

Burgess invited many people to broadcast. These included Blunt, the writer Harold Nicolson, the poet John Betjeman, and Kim Philby's father, St John Philby. Burgess also tried to get Winston Churchill to speak. Churchill was a strong opponent of the government's policy of appeasement at the time. On October 1, 1938, during the Munich crisis, Burgess visited Churchill at his home. He tried to convince Churchill to join a series of talks about Mediterranean countries. According to a biography, they talked about many things. Burgess urged Churchill to use his speaking skills to help solve the crisis. The meeting ended with Churchill giving Burgess a signed copy of his book. But the broadcast did not happen.

Burgess's Soviet handlers wanted him to join British intelligence. They asked him to become friends with David Footman, an MI6 officer. Footman introduced Burgess to his boss, Valentine Vivian. For the next eighteen months, Burgess did small, unpaid jobs for MI6. He was trusted enough to be a secret messenger. He passed messages between the British prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, and the French leader Edouard Daladier. This happened before the 1938 Munich summit.

At the BBC, Burgess felt his choices of speakers were being controlled by the government. He thought this was why Churchill didn't broadcast. In November 1938, after another speaker was removed at the prime minister's request, he resigned. MI6 was now sure he would be useful. He accepted a job with their new propaganda division, called Section D. Like other members of the Cambridge Five, he joined British intelligence without a full background check. His social standing and personal recommendations were enough.

Section D and Second Time at the BBC

MI6 created Section D in March 1938. It was a secret group that looked into ways to attack enemies without military action. Burgess worked as Section D's representative on the Joint Broadcasting Committee (JBC). This group was set up by the Foreign Office to work with the BBC. They planned anti-Hitler broadcasts to Germany. His contacts with senior government officials helped him keep Moscow informed about government plans. He told them that the British government did not think they needed an agreement with the Soviets. They believed Britain could defeat Germany alone. This information made the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin more suspicious of Britain. It may have helped speed up the Nazi-Soviet Pact, signed between Germany and the Soviet Union in August 1939.

After World War II started in September 1939, Burgess and Philby ran a training course. Philby had joined Section D because Burgess recommended him. The course was for people who wanted to cause trouble behind enemy lines. Philby later doubted how useful this training was. Neither he nor Burgess knew what these agents would actually do in German-occupied Europe. In 1940, Section D became part of the new Special Operations Executive (SOE). Philby went to a SOE training school. Burgess, who had been arrested for dangerous driving in September, found himself without a job at the end of the year.

In mid-January 1941, Burgess rejoined the BBC Talks Department. He also continued to do freelance intelligence work for both MI6 and MI5. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the BBC asked Burgess to find speakers who would show Britain's new Soviet ally in a good way. He again turned to Blunt and his old Cambridge friend Jim Lees. In 1942, he arranged a broadcast by Ernst Henri, a Soviet agent pretending to be a journalist. No record of Henri's talk exists, but listeners remembered it as pure Soviet propaganda.

In October 1941, Burgess took charge of The Week in Westminster. This important political show gave him almost unlimited access to Parliament. He regularly met MPs for drinks and lunches. The information he gathered from these talks was very valuable to the Soviets. Burgess tried to keep a political balance in his shows. Quintin Hogg, a future Conservative leader, was a regular speaker. So was Hector McNeil, a former journalist who became a Labour MP in 1941.

Burgess had lived in a flat in Chester Square since 1935. From Easter 1941, he shared a house with Blunt and others at No. 5 Bentinck Street. Here, Burgess had an active social life with his many friends. Goronwy Rees said the atmosphere at Bentinck Street was like a French play. He described "Bedroom doors opened and shut, strange faces appeared and disappeared down the stairs." Blunt disagreed, saying such casual visits were against house rules.

Burgess's casual work for MI5 and MI6 helped prevent officials from suspecting his true loyalties. But he constantly feared being exposed. He had told Rees the truth when trying to recruit him in 1937. Rees had since stopped being a communist and was serving as an officer. Burgess worried Rees might expose him and others. He suggested to his handlers that they should kill Rees, or that he should do it himself. Nothing came of this idea. Burgess always looked for ways to get closer to power. In June 1944, he was offered a job in the News Department of the Foreign Office, and he accepted it. The BBC reluctantly let him go, saying his departure would be "a serious loss."

Working for the Foreign Office

In London

As a press officer in the Foreign Office News Department, Burgess's job was to explain government policy. He talked to foreign editors and diplomatic reporters. He had access to secret information. This allowed him to send Moscow important details about allied policy. This included information before and during the March 1945 Yalta Conference. He passed on information about the future of Poland and Germany after the war. He also shared secret plans for "Operation Unthinkable," which imagined a future war with the Soviet Union. His Soviet bosses gave him a £250 bonus for his efforts. Burgess's work habits were often messy. He also talked too much. A colleague said that when he had too much to drink, he openly talked about working for the Russians.

Burgess stayed in touch with McNeil. After the Labour Party won the 1945 General Election, McNeil became Minister of State at the Foreign Office. He was effectively Ernest Bevin's deputy. McNeil was strongly against communism and did not suspect Burgess. He admired Burgess for his intelligence. In December 1946, McNeil arranged for Burgess to be an extra private secretary. This appointment broke normal Foreign Office rules, and there were complaints. But McNeil insisted. Burgess quickly became very important to McNeil. In one six-month period, he sent Moscow the contents of 693 files. This was over 2,000 photographed pages. For this, he received another £200 cash reward.

In early 1948, Burgess was temporarily moved to the Foreign Office's new Information Research Department (IRD). This department was set up to fight Soviet propaganda. The move was not successful. He was careless with secrets, and his new colleagues thought he was messy and lazy. He was quickly sent back to McNeil's office. In March 1948, he went with McNeil and Bevin to Brussels. They were there for the signing of the Treaty of Brussels. This treaty later led to the creation of the Western European Union and NATO. He stayed with McNeil until October 1948. Then, he was sent to the Foreign Office's Far East Department. Burgess worked on China issues. This was when the Chinese Civil War was ending, and a communist victory was coming. Britain and the U.S. had different ideas about future relations with the new communist state. Burgess strongly supported recognizing communist China. He may have influenced Britain's decision to recognize communist China in 1949.

In February 1949, Burgess had an accident. He fell downstairs and suffered serious head injuries. He was in the hospital for several weeks. His recovery was slow. According to one source, he never fully recovered after that.

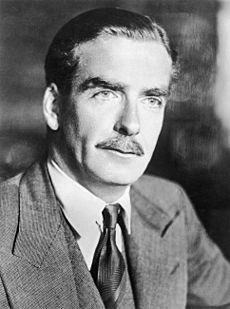

In Washington

Philby had gone to Washington before Burgess. He was the head of MI6 there. Maclean had also worked as the embassy's first secretary from 1944 to 1948. Burgess soon returned to his unpredictable and difficult habits. This often caused embarrassment in British diplomatic circles. Despite this, he was given very secret work. One of his jobs was on the international board for the Korean War. This gave him access to America's secret war plans. His frequent bad behavior did not stop him from being chosen to escort Anthony Eden. Eden, who would later become British prime minister, visited Washington in November 1950. The visit went smoothly. The two men, both from Eton, got along well. Burgess received a warm thank-you letter from Eden.

Burgess became increasingly unhappy with his job. He thought about leaving the diplomatic service completely. He started asking his Eton friend Michael Berry about a journalism job at The Daily Telegraph. In early 1951, he made several mistakes, including three speeding tickets in one day. This made his position at the embassy impossible. The ambassador, Sir Oliver Franks, ordered him to return to London.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Army's Venona counterintelligence project was investigating a Soviet spy called "Homer." This spy had been active in Washington a few years earlier. The project found strong evidence pointing to Donald Maclean. Philby and his Soviet spy masters believed that Maclean might break down if caught by British intelligence. This could expose the entire Cambridge spy ring. So, Burgess was given the task of arranging Maclean's escape to the Soviet Union once he reached London.

Leaving for the Soviet Union

The Escape

Burgess returned to England on May 7, 1951. He and Blunt then contacted Yuri Modin. Modin was the Soviet spymaster in charge of the Cambridge spy ring. Modin began making arrangements with Moscow to receive Maclean. Burgess did not seem to be in a hurry. He took time to deal with his personal matters and attend a dinner in Cambridge. On May 11, he was called to the Foreign Office to answer for his bad behavior in Washington. According to one account, he was fired. Other sources say he was asked to resign or "retire" and given time to think about it.

Burgess's diplomatic career was over. However, he was not suspected of being a traitor at this point. He met with Maclean several times. According to Burgess's 1956 account, the idea of going to Moscow was not brought up until their third meeting. That's when Maclean said he was leaving and asked for Burgess's help. Burgess had promised Philby that he would not go with Maclean. A double escape would put Philby's own position in serious danger. Blunt's private writings say that Moscow decided to send Burgess with Maclean. They thought Maclean would not be able to handle the escape alone. Burgess told a biographer that he agreed to go with Maclean because he was leaving the Foreign Office anyway. He also said he probably wouldn't like the job at the Daily Telegraph.

Meanwhile, the Foreign Office had set Monday, May 28, as the date to confront Maclean with their suspicions. Philby told Burgess. On Friday, May 25, Burgess bought two tickets for a weekend cruise on the steamship Falaise. These short cruises stopped at the French port of St Malo. Passengers could get off for a few hours without passport checks. Burgess also rented a car. That evening, he drove to Maclean's house in Surrey. He introduced himself to Maclean's wife, Melinda, as "Roger Styles." After dinner, Burgess and Maclean quickly drove to Southampton. They boarded the Falaise just before it left at midnight. The rented car was left abandoned at the dock.

The pair's later movements were revealed later. When they arrived in St Malo, they took a taxi to Rennes. Then they traveled by train to Paris and on to Berne in Switzerland. There, as planned, they received papers at the Soviet embassy. Then they traveled to Zurich, where they caught a flight to Prague. Once safely behind the Iron Curtain, they could easily continue their journey to Moscow.

What Happened Next

On Saturday, May 26, Hewit told a friend that Burgess had not come home the night before. Burgess never left without telling his mother, so his absence caused worry. Maclean's absence from his desk the following Monday raised concerns that he might have run away. Worry grew when officials realized Burgess was also missing. The discovery of the abandoned car, rented in Burgess's name, and Melinda Maclean's information about "Roger Styles," confirmed that both had fled. Blunt quickly visited Burgess's flat and removed any damaging materials. An MI6 search of the flat found papers that implicated another member of the Cambridge ring, Cairncross. He was later forced to resign from his government job.

The news of the double escape worried the Americans. This followed the recent conviction of atomic spy Klaus Fuchs and the defection of physicist Bruno Pontecorvo the year before. Philby knew his own position was now risky. He recovered various spying tools from Burgess's old Washington living quarters and buried them in a nearby wood. He was called to London in June 1951 and questioned by MI6 for several days. There were strong suspicions that he had warned Maclean through Burgess. But without clear evidence, he faced no action and was allowed to quietly leave MI6.

The Foreign Office did not make anything public right away. In private, many rumors spread. Some said the pair had been kidnapped by the Russians or Americans. Others thought they were on a secret peace mission. The press was suspicious, and the story finally broke in the Daily Express on June 7. A careful Foreign Office statement then confirmed that Maclean and Burgess were missing. They were considered absent without leave. In the House of Commons, the Foreign Secretary, Herbert Morrison, said there was no sign that the missing diplomats had taken secret documents. He also said he would not guess where they had gone.

On June 30, the Express offered a £1,000 reward for information on the diplomats' location. The Daily Mail soon offered £10,000. Many false sightings followed in the next months. Some news reports guessed that Burgess and Maclean were held in Moscow's Lubyanka prison. Just before Christmas 1953, Burgess's mother received a letter from her son. It was postmarked in South London. The letter was full of affection and messages for his friends. It did not reveal his location or situation.

Evidence against Burgess was not strong when he left. But it became clear with more investigation. Files from the KGB's Mitrokhin Archive, released in July 2014, showed that he had given over 389 top secret documents to the KGB in the first half of 1945. He also gave 168 more files in late 1949.

In April 1954, a senior officer, Vladmir Petrov, left his post in Australia. He brought papers showing that Burgess and Maclean had been Soviet agents since their Cambridge days. The MGB had planned their escape, and they were alive and well in the Soviet Union.

Life in the Soviet Union

After a short time in Moscow, Burgess and Maclean were sent to Kuybyshev. This was an industrial city that Burgess described as "permanently like Glasgow on a Saturday night." They became Soviet citizens in October 1951. Burgess took a new identity as "Jim Andreyevitch." Unlike Maclean, who learned the language and quickly found useful work, Burgess spent much of his time reading and complaining to the authorities. He had not planned for his stay to be permanent. He expected to be allowed to return to England. He thought he could handle any questioning from MI5. By early 1956, Burgess had moved back to Moscow. He lived in a flat on Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Street. He worked part-time at the Foreign Literature Publishing House. His job was to promote the translation of classic British novels.

In February 1956, the Soviet government allowed Burgess and Maclean to hold a short press conference. Two Western journalists were there: Richard Hughes from The Sunday Times and Sydney Weiland from Reuters. This was the first clear proof to the West that the missing diplomats were alive. In a short statement, they denied being communist spies. They said they had come to Moscow "to achieve better understanding between the Soviet Union and the West." In Britain, people strongly condemned their reappearance. Articles in The People, supposedly written by Burgess's former friend Rees, called Burgess "the greatest traitor in our history."

In July 1956, the Soviet authorities allowed Burgess's mother to visit her son. She stayed for a month, mostly at the holiday resort of Sochi. In August, the journalist and politician Tom Driberg flew to Moscow to interview Burgess. Driberg later wrote a book that showed Burgess in a somewhat positive light. Some thought the KGB had approved the book as propaganda. Others thought its purpose was to trick Burgess into revealing information that could lead to his arrest if he returned to Britain.

Over the next few years, Burgess had many visitors from England. Redgrave came with the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre Company in February 1959. This visit led to Burgess meeting the actress Coral Browne. Their friendship later became the subject of Alan Bennett's play An Englishman Abroad. In the same year, Burgess gave a filmed interview to the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). In it, Burgess said that while he wanted to keep living in Russia, he still loved his home country. When the British prime minister, Harold Macmillan, visited Moscow in 1959, Burgess offered his help to the visiting group. His offer was declined. But he used this chance to ask officials for permission to visit Britain. He said his mother was sick. The Foreign Office knew that a successful case against Burgess would be difficult. However, they issued statements implying he would be arrested immediately in Britain. In the end, Burgess chose not to test this.

Decline and Death

Burgess's health got worse. In 1960 and 1961, he was treated in the hospital for hardening of the arteries and ulcers. In 1961, he was close to death. In April 1962, he wrote to his friend Esther Whitfield. He told her how his belongings should be given away if he died. Blunt, Philby, and Chisekov were all named as people who would receive something.

In January 1963, Philby moved to Moscow. He had finally been revealed as a spy, after being cleared by Macmillan in November 1955. Philby and Burgess kept their distance. They might have met briefly when Burgess was dying in August 1963. Burgess died on August 30, 1963, from hardening of the arteries and severe liver failure. He was cremated five days later. Nigel Burgess represented the family. Maclean gave a speech, calling his fellow defector "a gifted and courageous man who devoted his life to the cause of a better world." Burgess's ashes were returned to England. On October 5, 1963, they were buried in the family plot at St. John the Evangelist Churchyard in West Meon.

Impact of His Actions

Modin, a Soviet spymaster, thought Burgess was the leader of the Cambridge spies. He said, "He held the group together, infused it with his energy and led it into battle." Burgess sent a lot of information to Moscow. This included thousands of documents, like policy papers and notes from important meetings. According to one historian, "Burgess and Maclean ensured that hardly anything done by the British Foreign Office was not known to the Soviet foreign intelligence services."

However, opinions differ on how useful this information was to the Soviets. Some wonder if they even trusted it. Released papers from Russian intelligence services show that "of particular value was the information [he] obtained about the positions of Western countries on the postwar settlement in Europe, Britain's military strategy, NATO [and] the activities of British and American intelligence agencies." But the easy way Burgess and his friends got and sent so much data also made Moscow suspicious. They wondered if they were being given false information. So, how much damage Burgess's spying caused to British interests is still debated. One biographer concluded that there is "too little evidence on the effects of [Burgess's] espionage and his influence upon international politics for a credible assessment to be feasible."

The British government found it hard to understand how someone from Burgess's background could betray his country. According to Rebecca West, the sadness and panic caused by Burgess's defection were more valuable to the Soviets than the information he passed. The damage to intelligence sharing between Britain and the U.S. was severe. All atomic intelligence cooperation between the two countries was stopped for several years. The Foreign Office became less relaxed about hiring and security. Even though background checks were later introduced, the diplomatic service suffered from "a culture of suspicion and mistrust." This lasted for half a century after the 1951 escape.

Against the popular labels of "traitor" and "spy," Burgess was, in one historian's words, a revolutionary and an idealist. He agreed with those who thought their society "was deeply unjust." He never changed the reason he gave for his actions in 1956. He believed that in the twentieth century, the clear choice was between America and the Soviet Union. One writer said that Burgess "was a true Stalinist who hated liberals more than imperialists." He "simply believed that Britain's future lay with Russia not America." Burgess insisted there was no strong legal case against him in England. This was a view secretly shared by British authorities. But he would not visit Britain. He said he might be stopped from returning to Moscow, where he wanted to live "because I am a socialist and this is a socialist country."

One biographer says that Burgess's life can only be understood by looking at "the intellectual maelstrom of the 1930s." This was especially true for young and impressionable people. Yet, he points out that most of his fellow Cambridge communists did not work for the Russians. Many even changed their views after the Nazi-Soviet Pact. Another historian emphasizes the high cost of Burgess's continued political commitment. It "cost him everything else he valued: the possibility of fulfilling intimate relationships, the social life that revolved around the BBC, Fleet Street and Whitehall, even the chance to be with his mother as she lay dying."

Of the other Cambridge spies, Maclean and Philby lived their lives in Moscow. They died in 1983 and 1988. Blunt was questioned many times. He finally confessed in 1964. But this was not made public until 1979. He died four years later. Cairncross made a partial confession in 1964. He continued to work with British authorities. He worked as a writer and historian before his death in 1995.

Parts of Burgess's life have been used in several books and plays. An early novel was The Troubled Midnight (1954) by Rodney Garland. Others include Nicholas Monsarrat's Smith and Jones (1963) and Michael Dobbs's Winston's War (2003). This last book builds on the pre-war meeting between Burgess and Churchill. Plays and films include Bennett's An Englishman Abroad. There was also Granada TV's 1987 drama Philby, Burgess and Maclean (1977). The 2003 BBC miniseries Cambridge Spies also covered their story. John Morrison's 2011 play A Morning with Guy Burgess is set in his last months. It looks at themes of loyalty and betrayal.

Two biographies of Guy Burgess were published in 2016. This happened after secret files were released to the National Archives. The conclusions in both books support what Andrew Lownie said. He stated "that it was Burgess, rather than the notorious Philby, who was the real ringleader of the traitorous circle, and that Guy was a world-class networker."

See also

In Spanish: Guy Burgess para niños

In Spanish: Guy Burgess para niños

- Mitrokhin Archive

- Information Research Department

Images for kids

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |