History of Slovakia facts for kids

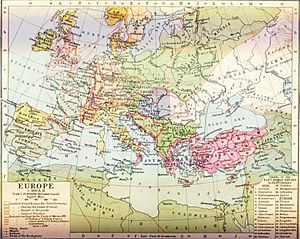

The history of Slovakia tells the story of this country from ancient times to today. It's a journey through many different periods, showing how the land and its people changed over thousands of years.

Contents

Ancient Times

People have lived in Slovakia for a very long time. Tools found near Nové Mesto nad Váhom show that humans were here during the Stone Age. Other old discoveries include stone tools near Bojnice and a Neanderthal site near Gánovce. A famous ancient artwork, the Venus of Moravany, was found in Moravany nad Váhom.

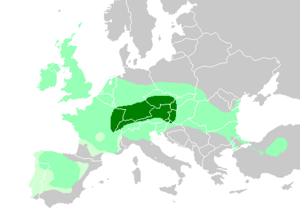

Later, during the New Stone Age, people lived in places like Želiezovce and the Domica cave. The Bronze Age saw different cultures, like the Unetice culture and Lusatian culture. The early Iron Age brought the Hallstatt culture.

Celts and Romans

The Celts were the first people in Slovakia that we know about from written records. They arrived from the west around 400 BC. They settled in the lowlands near the Danube river. Some Celtic towns became important centers for trade and administration. For example, Zemplín was known for iron, and Liptovská Mara had glassworks. Coins were even made in Bratislava and Liptovská Mara.

Around 60 BC, Burebista, the King of the Dacians, took over many Celtic tribes. But his empire fell apart after he died. Later, Romans and Germanic tribes started to move into the area. Roman soldiers crossed the Danube to fight the Germanic Quadi tribe.

The Danube River was the border between the Roman Empire and the "Barbaricum" (lands outside the empire). But the Romans still built small forts on the other side, like at Iža and Devín. During the Marcomannic Wars (160-180 AD), Roman troops crossed the Danube many times. Emperor Marcus Aurelius even wrote part of his famous book, Meditations, while on a campaign near the Hron River in 172 AD.

Medieval History

New Peoples Arrive

In the 4th century AD, the Roman Empire became weaker. The Huns, a powerful nomadic group, took control of the Carpathian Basin in the early 5th century. Many Germanic tribes, like the Quadi, had to leave their homes. The Huns, led by Attila the Hun, ruled the area.

After Attila died in 453 AD, his empire broke apart. The Germanic peoples either became free or left the region. Graves from this time show many weapons, meaning there was a lot of fighting.

Arrival of the Slavs

Historians believe the first Slavic groups settled in eastern Slovakia as early as the 4th century. By the 6th century, new Slavic settlements appeared, often with small huts and handmade pottery. These settlements are linked to the spread of the early Slavs.

The Longobards, another Germanic tribe, moved into the Middle Danube region in the early 6th century. They mostly avoided Slovakia, settling only in the northwest (Záhorie). This meant that Slovakia, unlike nearby Moravia, was not part of a German empire at this time.

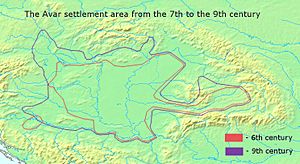

Avar Khaganate

In 568 AD, the Avars, a group of nomadic warriors, invaded the Carpathian Basin. The Longobards left for Italy. By this time, Slavs had settled in most of what is now Slovakia. The Avars took control, and the Slavs became their subjects.

The Chronicle of Fredegar tells us that the Slavs rebelled against the Avars in 623 or 624 AD. They chose a Frankish merchant named Samo as their king. Samo ruled for 35 years, and his kingdom was likely near the Danube and Morava rivers. After Samo's death, his kingdom fell apart.

In the 8th century, the Slavs in Slovakia improved their farming and crafts. They started building strong, fortified settlements called hradisko (large forts) with thick walls and trenches. This shows that a Slavic upper class was forming, which would later become the core of Great Moravia.

The Franks fought a series of wars against the Avars (788–803 AD), leading to the Avars' political decline. The Slavs also attacked Avar centers like Devín and Komárno, pushing the Avars out of some areas.

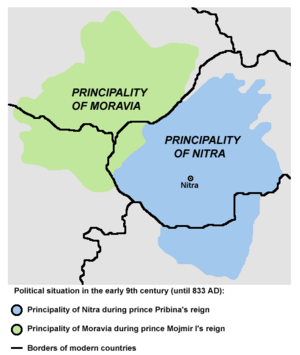

Principality of Nitra

Around 870 AD, a text called the Conversio Bagoariorum et Carantanorum mentions that Mojmir, the leader of the Moravians, expelled a ruler named Pribina. Pribina then joined Radbod in the Carolingian Empire.

Some historians believe that Pribina had his own church consecrated in a place called "Nitrava," which is thought to be Nitra in modern-day Slovakia. When Mojmir I took over Pribina's Principality of Nitra, it led to the creation of a new state called "Great Moravia".

Archaeological findings show that several important forts in Slovakia fell around the time Pribina was expelled. It's not fully clear if this was due to internal changes or Moravian expansion.

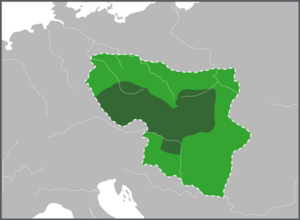

Great Moravia

Great Moravia began around 830 AD when Mojmír I united Slavic tribes north of the Danube. When Mojmír I tried to become fully independent from the Frankish king in 846, King Louis the German replaced him with his nephew, Rastislav.

Rastislav wanted to be independent. He asked the Byzantine Emperor Michael III to send teachers who could explain Christianity in the Slavic language. So, in 863 AD, two brothers, Saints Cyril and Methodius, arrived. Cyril created the first Slavic alphabet and translated the Bible into Old Church Slavonic. Rastislav also built many fortified castles to protect his state.

During Rastislav's rule, his nephew Svätopluk was given the Principality of Nitra. Svätopluk later allied with the Franks and overthrew his uncle in 870. Svätopluk I (871–894) became king and expanded Great Moravia to its largest size. It included not only present-day Moravia and Slovakia but also parts of Hungary, Austria, Bohemia, and Poland.

In 880, Pope John VIII created an independent church region in Great Moravia. After King Svätopluk died in 894, his sons, Mojmír II and Svatopluk II, fought for control. This weakened the empire.

Around 896, the Hungarian tribes, after being defeated by the Pechenegs, moved into the Pannonian Basin and started to take over the territory. Both Mojmír II and Svätopluk II likely died fighting the Hungarians between 904 and 907. In 907, the Hungarians defeated Bavarian armies in three battles near Bratislava. This year is usually seen as the end of the Great Moravian Empire.

Great Moravia left a lasting impact. The Glagolitic script and its later version, Cyrillic, spread to other Slavic countries.

High Middle Ages

Hungarian Settlement in the 10th Century

From 895 to 902, the Hungarians gradually took control of the Pannonian Basin. Even though some sources say Great Moravia disappeared, archaeological findings show that Slavic people continued to live in the river valleys of the Carpathian Mountains.

The oldest Hungarian graves in Slovakia are from the late 9th and early 10th centuries. By 930-940, larger groups of Hungarians moved into southern Slovakia. They did not cross a line from Bratislava to Nitra and other towns further east. In southern Slovakia, Hungarians often built their villages near older Slavic settlements. They sometimes joined them and used the same cemeteries.

Principality of Nitra (11th Century)

The future Kingdom of Hungary began to form under Grand Prince Géza (before 972–997). He expanded his rule over parts of present-day Slovakia. His son, Stephen, became the first King of Hungary in 1000 or 1001.

King Stephen set up at least eight counties in what is now Slovakia, including Nitra and Zemplín. He also established church areas (dioceses). In the 11th century, parts of Slovakia were under the Archdiocese of Esztergom.

After King Stephen died, his kingdom faced internal conflicts. In 1048, King Andrew I of Hungary gave one-third of his kingdom, called Tercia pars regni, to his brother, Duke Béla. This area was centered around Nitra. For the next 60 years, this part of the kingdom was governed separately by members of the royal family. The history of Tercia pars regni ended in 1107 when King Coloman of Hungary took control of its territories.

Mongol Invasion (1241–1242)

In 1241, the Mongols invaded and destroyed parts of the kingdom. The Mongolian army crossed into Moravia and plundered areas along the Váh and Nitra rivers. Only strong castles like Trenčín Castle, Nitra, and Fiľakovo could resist. Many people died from famine and disease.

After the Mongols left, King Béla IV of Hungary ordered many castles to be built or strengthened, such as Komárno and Zvolen. Towns also became more important for both economy and defense.

Development of Counties and Towns

Slovakia was rich in materials like gold, silver, copper, iron, and salt. This led to the growth of mining. Many towns received special rights from the kings, like Trnava (1238) and Košice (before 1248).

People from other areas, like Walloons, Germans, and Poles, came to settle in the less populated northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary. German settlers played a big role in developing towns, bringing new ways of production and legal systems.

In the Middle Ages, Slovakia was one of the most urbanized and economically important regions of the Kingdom of Hungary. Many royal towns and mining towns were located here. For example, Kremnica produced a lot of gold, and Banská Štiavnica and Banská Bystrica produced much of the kingdom's silver.

Towns formed unions to protect their rights. The most important were the Community of Saxons of Spiš and the Lower Hungarian Mining Towns. The people in these towns were mainly German, but also Slovaks and Hungarians.

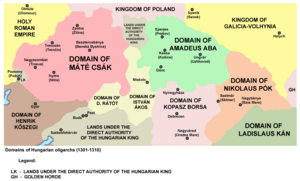

Period of the Oligarchs (1290–1321)

The late 13th century saw conflicts within the royal family and among powerful nobles. This led to a decline in royal power and the rise of "oligarchs" – powerful aristocrats who controlled large territories.

In Slovakia, most castles were owned by two powerful nobles: Amade Aba and Matthew III Csák. They ruled their lands almost independently. Amade Aba controlled eastern Slovakia, but he was killed in Košice in 1311.

Matthew III Csák ruled western Slovakia from Trenčín. He fought against King Charles I of Hungary, but the king's armies defeated him in the Battle of Rozgony in 1312. However, Matthew kept control of his areas until he died in 1321.

Late Middle Ages (14th–15th Centuries)

King Charles I strengthened the central power in the kingdom. He made trade agreements that helped towns like Košice and Žilina. The king confirmed the rights of many towns, and some, like Bratislava and Košice, became "free royal cities". This meant they had special rights and could send representatives to royal assemblies.

The population in northern Slovakia grew, and new counties like Orava and Liptov were formed. In 1412, King Sigismund mortgaged 13 "Saxon" towns in Spiš to Poland. They remained under Polish control until 1769.

Most of the land in Slovakia was owned by the kings, but also by church leaders and noble families. After King Albert died in 1439, a civil war started. Mercenaries from Bohemia, led by Jan Jiskra, captured several towns in Slovakia. He held them until 1462 when he surrendered to King Matthias Corvinus.

Modern Era

Early Modern Period

Habsburg and Ottoman Rule

The Ottoman Empire conquered the central part of the Kingdom of Hungary. This meant that much of present-day Slovakia became part of the Habsburg monarchy. This remaining part was still called the Kingdom of Hungary, but some historians call it "Royal Hungary".

After the Ottomans took Buda in 1541, Bratislava became the capital and coronation city of the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary. Many Habsburg rulers were crowned here.

For almost 200 years, Slovakia was a battleground in wars against the Ottoman expansion. The region suffered greatly, losing many lives and much property. Natural resources like gold and silver were used to pay for the wars.

Parts of Slovakia were even included in Ottoman provinces. For example, the Uyvar Eyalet had its center in Nové Zámky. In the late 17th century, a vassal Ottoman principality was set up in eastern Hungary, led by Prince Imre Thököly.

After the Ottomans were pushed out of Buda in 1686, Buda (later Budapest) became the capital again. Even after centuries under Hungarian, Habsburg, and Ottoman rule, the Slovak people managed to keep their language and culture.

Late Modern Period

Slovak National Movement

In the 18th century, the Slovak National Movement began. It aimed to create a stronger sense of national identity among Slovaks. This movement grew in the 19th century, led mainly by Slovak religious leaders. However, Hungarian control remained strong, and the policy of magyarization (making things more Hungarian) limited the movement.

The first official Slovak language was created by Anton Bernolák in the 1780s. Later, in the 1840s, Ľudovít Štúr developed a new standard language based on central Slovak dialects. This version was accepted by both Catholics and Lutherans in 1847 and is the basis of modern Slovak.

Hungarian Revolution of 1848

In the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Slovak leaders supported the Austrians. They hoped to separate from the Kingdom of Hungary and gain more freedom within the Austrian monarchy. The Slovak National Council even organized an uprising.

After the Hungarian Revolution was defeated, the Austrian authorities divided the Kingdom of Hungary into five military districts. Two of these had administrative centers in Slovakia: Bratislava and Košice.

In 1863, the cultural association Matica slovenská was founded in Martin, which became a center for the Slovak National Movement.

Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

In 1867, the Habsburg lands became the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Slovakia was part of the Hungarian side, where the Hungarian elite did not trust Slovak leaders because of their Pan-Slavism (unity of all Slavs) and desire for separation. Matica slovenská was closed down in 1875, and other Slovak institutions faced similar problems.

By the end of the 19th century, Slovaks realized they needed allies. They worked with Czechs to support the idea of Slovaks leaving the Kingdom of Hungary.

In the early 20th century, there was a growing call for universal suffrage (the right to vote for everyone). Slovaks hoped this would ease ethnic oppression. The Slovak political movement split into different groups.

One important event was the Černová tragedy in 1907, where 15 Slovaks were killed during a riot. This incident drew international attention to the violation of rights for non-Hungarian minorities.

Before World War I, Archduke Franz Ferdinand had a plan to federalize the monarchy, which included Slovak autonomy. However, his assassination triggered World War I, and the plan was abandoned.

Czechoslovakia

Formation of Czechoslovakia

After World War I (1914–1918), Slovaks decided to leave the Dual Monarchy and form an independent republic with the Czechs. Slovaks living abroad, especially in the United States, strongly supported this idea.

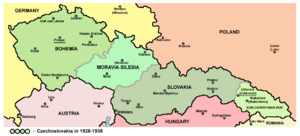

Milan Rastislav Štefánik, a Slovak who was a French general, played a key role in creating the new state. On October 28, 1918, the Prague National Committee declared the independent republic of Czechoslovakia. Two days later, the Slovak National Council in Martin joined this declaration. The new republic included the Czech lands, Slovakia, and Subcarpathian Ruthenia, with its capital in Prague.

In May–June 1919, the Hungarian Red Army attacked, pushing Czech troops out of central and eastern Slovakia. A short-lived Slovak Soviet Republic was set up in Prešov. However, the Hungarian army later withdrew.

The Treaty of Trianon in 1920 set the southern border of Czechoslovakia. Some areas with mostly Hungarian populations were included in Czechoslovakia for strategic and economic reasons.

First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938)

Slovaks were outnumbered by Czechs in the new state. Slovakia was more agricultural and less developed than the Czech lands. Most Slovaks were Catholic, while fewer Czechs followed traditional religions. Slovaks also had less education and experience with self-government. These differences, along with centralized control from Prague, caused some unhappiness among Slovaks.

Czechoslovakia remained a parliamentary democracy during this time. However, it faced problems with minorities, especially the large German population. Many Slovaks wanted more autonomy for Slovakia. This movement grew until Slovakia declared independence in 1939.

The Czechoslovak government tried to industrialize Slovakia between the world wars, but these efforts were not very successful, partly due to the Great Depression. Slovak resentment over Czech economic and political control led to more support for independence. Many Slovaks joined Father Andrej Hlinka and Jozef Tiso in calling for equality and greater autonomy for Slovakia.

Towards Autonomy of Slovakia (1938–1939)

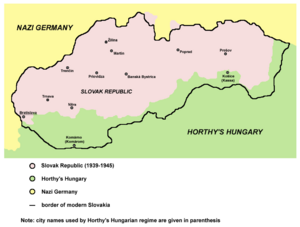

In September 1938, the Munich Agreement forced Czechoslovakia to give the German-speaking Sudetenland region to Nazi Germany. In November, the First Vienna Award forced Czechoslovakia to give southern Slovakia, which had many Hungarian speakers, to Hungary.

On March 14, 1939, the Slovak Republic declared its independence. It became a state under Nazi German control. Jozef Tiso became Prime Minister and later President.

On March 15, Nazi Germany invaded the rest of the Czech lands, creating the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Hungary also invaded and took over Carpatho-Ukraine and parts of eastern Slovakia. This led to a short conflict called the Slovak-Hungarian War.

World War II

The independent Slovak Republic was an Axis ally. It took part in the wars against Poland and the Soviet Union. Its contribution to the German war effort was small, but the number of Slovak troops was significant for a country of its size.

Under Jozef Tiso's government, measures were taken against the 90,000 Jews in the country. The Hlinka Guard attacked Jews, and the "Jewish Code" was passed in September 1941. This code was similar to the Nuremberg Laws and forced Jews to wear a yellow armband and banned them from many jobs. More than 64,000 Jews lost their livelihoods. Between March and October 1942, about 57,000 Jews were sent to German-occupied Poland, where most were killed in Extermination camps. Later, in 1944, German forces deported 12,600 more Jews after the Slovak National Uprising.

On August 29, 1944, 60,000 Slovak troops and 18,000 partisans rebelled against the Nazis. This was the Slovak National Uprising. Slovakia was heavily damaged by the German counter-attack, but guerrilla fighting continued. The uprising was important because it allowed Slovaks to be seen as contributing to the Allied victory.

In late 1944, Soviet attacks increased. The Red Army, with Romanian help, gradually pushed the German army out of Slovakia. On April 4, 1945, Soviet troops entered Bratislava, the capital.

Czechoslovakia After World War II

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was restored in 1945, but without Carpathian Ruthenia, which went to the Soviet Union. The Beneš decrees led to the persecution of the Hungarian minority and the expulsion of the German minority in Slovakia.

Elections were held in 1946. The Democratic Party won in Slovakia, but the Czechoslovak Communist Party won in the Czech part. In February 1948, the Communists took power, making Czechoslovakia a satellite state of the Soviet Union.

The next four decades were under strict Communist control. There was a brief period of reform in 1968, known as the Prague Spring, when Alexander Dubček (a Slovak) tried to create "socialism with a human face". However, other Warsaw Pact countries worried he went too far. On August 21, 1968, Soviet, Hungarian, Bulgarian, East German, and Polish troops invaded and occupied Czechoslovakia. Another Slovak, Gustáv Husák, replaced Dubček as Communist Party leader.

The 1970s and 1980s were called "normalization". During this time, the government suppressed any opposition. Slovakia experienced this period less harshly than the Czech lands and saw some economic growth.

A dissident movement developed in the 1970s, especially in the Czech Republic. In 1977, over 250 human rights activists signed Charter 77, criticizing the government for not respecting human rights.

Velvet Revolution (1989)

On November 17, 1989, public protests known as the "Velvet Revolution" began. These protests led to the end of Communist Party rule in Czechoslovakia. A new government was formed in December 1989, and the first free elections since 1948 took place in June 1990.

In 1992, talks about a new federal constitution failed over the issue of Slovak autonomy. An agreement was reached to peacefully dissolve Czechoslovakia. On January 1, 1993, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic became independent countries. Both states were immediately recognized by other nations.

After the Velvet Revolution, groups like Charter 77 formed the Civic Forum, which pushed for reforms and civil liberties. Its leader, Václav Havel, became President of Czechoslovakia. The Slovak group, Public Against Violence, shared similar goals.

In the 1990 elections, Civic Forum and Public Against Violence won by a lot. However, they found it harder to govern than to overthrow the old system. In the 1992 elections, new parties replaced them.

Contemporary Period

Independent Slovakia

In the election in June 1992, Václav Klaus's party won in Czechia, and Vladimír Mečiar's Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS) became the leading party in Slovakia, supporting Slovak autonomy. Mečiar and Klaus agreed to divide Czechoslovakia. Mečiar's party ruled Slovakia for most of its first five years as an independent state.

The first president of independent Slovakia was Michal Kováč. The first prime minister, Mečiar, had been prime minister of the Slovak part of Czechoslovakia since 1992.

Rudolf Schuster won the presidential election in May 1999. Mečiar's government was replaced after the 1998 parliamentary elections by a coalition led by Mikuláš Dzurinda.

Dzurinda's first government made many political and economic reforms. These reforms helped Slovakia join the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and become a strong candidate for joining the European Union (EU) and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

In the September 2002 parliamentary election, Prime Minister Dzurinda's party, the Slovak Democratic and Christian Union (SDKÚ), gained enough support for a second term. He formed a government with three other parties. This new government focused on joining NATO and the EU, attracting foreign investment, and reforming social services.

Slovakia joined NATO on March 29, 2004, and the EU on May 1, 2004. In 2005, Slovakia was elected to a two-year term on the UN Security Council.

The election in June 2010 was won by the leftist Smer party, but its leader, Robert Fico, could not form a government. A coalition of other parties took over, with Iveta Radičová becoming Slovakia's first woman prime minister. This government fell after a vote related to the European Financial Stability Fund.

Smer won the election in 2012 with a large majority. Fico formed his Second Cabinet, a single-party government. It supported the EU's position during the Russian military invasion of Ukraine but sometimes questioned the effectiveness of EU sanctions against Russia. In 2015, the leaders of the four Visegrád Group states rejected the EU's proposal to reallocate refugees.

The election in March 2016 saw Fico form his Third Cabinet, made up of four parties.

Fico resigned as prime minister in March 2018 after large street protests. These protests followed the murder of Ján Kuciak, an investigative journalist who was looking into high-level political corruption. President Andrej Kiska appointed Peter Pellegrini to replace Fico.

In March 2019, Zuzana Čaputová was elected as the first female president of Slovakia.

After the 2020 Slovak parliamentary election, the Ordinary People and Independent Personalities party won, and Igor Matovič became prime minister in March 2020. In April 2021, Eduard Heger became prime minister after Matovič resigned. In May 2023, Heger resigned, and Ľudovít Ódor became caretaker prime minister.

In September 2023, the populist left-wing Smer-SSD party, led by former prime minister Robert Fico, won the general election. Fico became prime minister again on October 25, 2023. He announced that the new government would stop Slovakia's military aid to Ukraine and would not support further sanctions against Russia. In April 2024, Peter Pellegrini, a close ally of Fico, won the presidential election.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Eslovaquia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Eslovaquia para niños

- Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

- History of Bratislava

- History of Czechoslovakia

- History of the Czech Republic

- History of the Jews in Slovakia

- History of the Slovak language

- Politics of Slovakia

- Slovaks in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

Lists:

- List of presidents of Czechoslovakia

- List of prime ministers of Czechoslovakia

- List of presidents of Slovakia

- List of prime ministers of Slovakia

General:

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |