Eleftherios Venizelos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Eleftherios Venizelos

|

|

|---|---|

| Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος | |

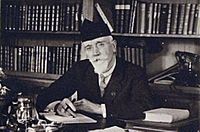

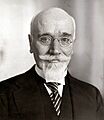

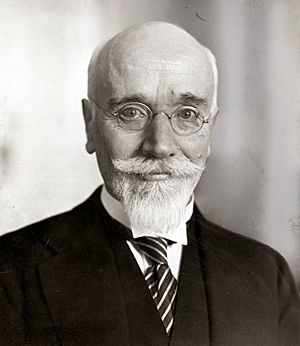

Eleftherios Venizelos in 1935

|

|

| Prime Minister of Greece | |

| In office 16 January 1933 – 6 March 1933 |

|

| President | Alexandros Zaimis |

| Preceded by | Panagis Tsaldaris |

| Succeeded by | Alexandros Othonaios |

| In office 5 June 1932 – 4 November 1932 |

|

| President | Alexandros Zaimis |

| Preceded by | Alexandros Papanastasiou |

| Succeeded by | Panagis Tsaldaris |

| In office 4 July 1928 – 26 May 1932 |

|

| President | Pavlos Kountouriotis Alexandros Zaimis |

| Preceded by | Alexandros Zaimis |

| Succeeded by | Alexandros Papanastasiou |

| In office 24 January 1924 – 19 February 1924 |

|

| Monarch | George II |

| Preceded by | Stylianos Gonatas |

| Succeeded by | Georgios Kafantaris |

| In office 14 June 1917 – 4 November 1920 |

|

| Monarch | Alexander |

| Preceded by | Alexandros Zaimis |

| Succeeded by | Dimitrios Rallis |

| In office 10 August 1915 – 24 September 1915 |

|

| Monarch | Constantine I |

| Preceded by | Dimitrios Gounaris |

| Succeeded by | Alexandros Zaimis |

| In office 6 October 1910 – 25 February 1915 |

|

| Monarch | George I Constantine I |

| Preceded by | Stefanos Dragoumis |

| Succeeded by | Dimitrios Gounaris |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 23 August 1864 Mournies, Crete, Ottoman Empire (now Eleftherios Venizelos, Crete, Greece) |

| Died | 18 March 1936 (aged 71) Paris, France |

| Political party | Liberal Party |

| Spouses | Maria Katelouzou (1891–1894) Helena Schilizzi (1921–1936) |

| Relations | Konstantinos Mitsotakis (nephew) Kyriakos Mitsotakis (grand-nephew) |

| Children | Kyriakos Venizelos Sophoklis Venizelos |

| Alma mater | National and Kapodistrian University of Athens |

| Profession | Politician Revolutionary Legislator Lawyer Jurist Journalist Translator |

| Signature | |

| Website | National Foundation Research "Eleftherios K. Venizelos" |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | Greco-Turkish War (1897)

|

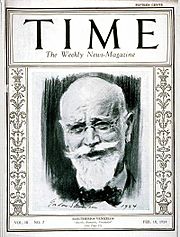

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos (born August 23, 1864 – died March 18, 1936) was a very important Greek leader and politician. He helped Greece grow bigger and promoted ideas about democracy. As the head of the Liberal Party, he was the prime minister for over 12 years, serving eight times between 1910 and 1933. People often call him "The Maker of Modern Greece" because he changed the country so much. He is also known as the "Ethnarch", which means a national leader.

Venizelos first became known internationally for his big role in making Crete an independent state. Later, he helped unite Crete with Greece. In 1909, he was asked to come to Athens to fix political problems and became the country's Prime Minister. He started important changes to the constitution and the economy, which helped modernize Greek society. He also made the army and navy stronger for future fights.

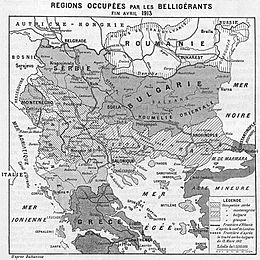

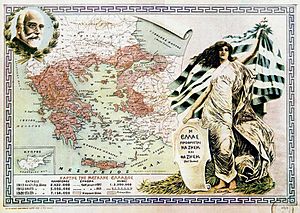

Before the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), Venizelos helped Greece join the Balkan League. This was an alliance of Balkan countries against the Ottoman Empire. Thanks to his smart diplomacy, Greece doubled its size and population. It gained Macedonia, Epirus, and many Aegean islands.

During World War I (1914–1918), he brought Greece to the side of the Allies. This helped Greece expand its borders even more. However, his choice caused a big disagreement with Constantine I of Greece, the King. This led to the "National Schism", which divided the Greek people into two main groups: those who supported the King (royalists) and those who supported Venizelos (Venizelists). This power struggle affected Greece for many years.

After the Allies won the war, Venizelos gained more land for Greece, especially in Anatolia. He was very close to achieving the "Megali Idea", a dream of a larger Greece. But he lost the 1920 election. This loss contributed to Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22). Venizelos then went into exile. He later represented Greece in talks that led to the Treaty of Lausanne. This treaty also arranged for a population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

In his later times as prime minister, Venizelos improved relations with Greece's neighbors. He also continued his constitutional and economic reforms. In 1935, he supported a military coup. But the coup failed, which weakened the Second Hellenic Republic.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Family Background and Childhood

Eleftherios Venizelos was born in Mournies, a place near Chania in Crete. At that time, Crete was part of the Ottoman Empire. His father, Kyriakos Venizelos, was a merchant and a revolutionary. His mother was Styliani Ploumidaki.

When the Cretan revolution of 1866 started, Venizelos' family had to leave Crete. This was because his father was involved in the revolution. They went to the island of Syros and stayed there until 1872, when they were allowed to return to Crete.

School and University Years

Eleftherios finished his secondary education in Ermoupolis, Syros, in 1880. In 1881, he started studying law at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. He graduated with excellent grades.

After finishing his studies in 1886, he returned to Crete and worked as a lawyer in Chania. He loved reading and always worked to improve his skills in English, Italian, German, and French.

Starting in Politics

Crete was a very unstable place when Venizelos was young. The Ottoman Empire was not keeping its promises for reforms. Many Cretans wanted to unite with Greece.

In these difficult times, Venizelos entered politics in 1889. He was part of the island's liberal party. As a representative, he was known for his strong speeches and new ideas.

Political Career in Crete

The Cretan Uprising

Why the Uprising Happened

Crete had many revolutions because Cretans wanted to unite with Greece. After the 1866 revolution, an agreement called the Pact of Chalepa gave Cretans more self-rule. This was meant to stop them from rebelling against the Ottomans.

However, the Ottoman Empire did not follow the rules of the Pact. This made tensions worse between the Christian Greek population and the Muslim population on the island. Violence increased, especially against Christians in 1897.

The Greek government sent warships and soldiers to protect the Cretan Greeks. Other powerful countries, called the Great Powers, decided to take over the island. But they were too late. A Greek force landed in Crete and announced that Crete was uniting with Greece. This led to a big uprising across the island.

Venizelos at Akrotiri

Venizelos was traveling around Crete for elections when he saw Chania burning. He quickly went to Malaxa, near Chania, where about 2,000 rebels had gathered. He became their leader.

Venizelos and the rebels attacked the Turkish forces at Akrotiri. They raised a Greek flag. The Ottoman forces asked for help from foreign admirals. The ships of the Great Powers started firing at the rebel positions. When a shell knocked down the flag, it was immediately raised again.

Venizelos wrote a strong protest letter to the foreign admirals. He said the rebels would stay until they were all killed, rather than let the Turks stay in Crete. This letter was shared with international newspapers. It made many people in Greece and Europe angry that Christian ships were firing on Christians who wanted freedom.

The War in Thessaly

The Great Powers suggested that Crete become an independent state under the Ottoman Sultan. The Greek government refused, insisting on union with Greece.

Venizelos met with the admirals of the Great Powers. He convinced them to let him tour the island to see what people wanted. Most Cretans initially wanted union with Greece.

Because of the rebellion in Crete, the Ottomans moved their army to Thessaly, near Greece's borders. Greece also sent more soldiers. However, some unofficial Greek groups attacked Turkish outposts. This led the Ottoman Empire to declare war on Greece in April 1897.

The war was a disaster for Greece. The Turkish army was much better prepared. The Greek army quickly retreated. The Great Powers stepped in again, and a ceasefire was signed.

The Outcome for Crete

Even though Greece lost the war, it was a diplomatic win for Crete. The Great Powers (Britain, France, Russia, and Italy) decided that Crete would become an autonomous state. This meant it would govern itself but still be under the Ottoman Sultan.

Venizelos played a key role in this solution. He was not only a rebel leader but also a skilled diplomat. He talked often with the admirals of the Great Powers. The four Great Powers took over the administration of Crete. Prince George of Greece, the son of King George I of Greece, became the High Commissioner. Venizelos served as his Minister of Justice from 1899 to 1901.

Autonomous Cretan State

Prince George of Greece was appointed High Commissioner of the Cretan State for three years. In April 1899, he created an Executive Committee with Cretan leaders. Venizelos became the Minister of Justice. They started to organize the state and create a "Cretan constitution." Venizelos made sure the constitution did not mention religion, so all residents felt represented.

However, disagreements started between Venizelos and Prince George. The Prince wanted to build a palace, but Venizelos was against it. He believed it would make the governorship permanent, while Cretans saw it as temporary until union with Greece.

Venizelos believed that Crete was not truly independent because foreign troops were still there. He thought that once the Prince's term ended, the Great Powers should be asked to let the Committee elect a new ruler. This would make it easier to unite with Greece later. His opponents used this idea against him, saying he wanted Crete to be a separate kingdom.

Venizelos resigned many times. Finally, on March 6, 1901, he explained his reasons for resigning in a report that was leaked to the press. On March 20, Venizelos was officially dismissed. He then became the leader of the opposition against the Prince. Their conflict grew, and the island's government almost stopped working. This led to the Theriso revolt in March 1905, which Venizelos led.

The Theriso Revolution

On March 10, 1905, rebels gathered in Theriso and declared that Crete was politically uniting with Greece. They sent this resolution to the Great Powers, arguing that the current setup was hurting Crete's economy. They said that uniting with Greece was the only real solution.

The High Commissioner and the Great Powers threatened to use military force against the rebels. But more and more people joined Venizelos in Theriso. The Great Powers' representatives met with Venizelos, but they couldn't reach an agreement.

The revolutionary government asked for Crete to have a similar government to Eastern Rumelia. On July 18, the Great Powers declared martial law, but this did not stop the rebels. On August 15, the assembly in Chania voted for most of Venizelos' proposed changes. The Great Powers' representatives met Venizelos again and accepted his reforms.

This led to the end of the Theriso revolt. Prince George resigned as High Commissioner. The Great Powers allowed King George I of Greece to choose the new High Commissioner. This basically ended Ottoman rule over Crete. Alexandros Zaimis, a former Greek Prime Minister, was chosen. Greek officers were allowed to organize the Cretan Gendarmerie (police force). Once the police were organized, foreign troops started leaving the island. This was a big win for Venizelos, making him famous in Greece and Europe.

After the Young Turk Revolution in 1908, Bulgaria declared independence from the Ottoman Empire. Austria also took over Bosnia-Herzegovina. Encouraged by these events, Cretans also rose up on the same day. Thousands gathered in Chania, and Venizelos declared the union of Crete with Greece.

An assembly was called and declared Crete's independence. Government workers swore loyalty to King George I of Greece. A five-member committee was set up to control the island for the King. Venizelos became Minister of Justice and Foreign Affairs. By April 1910, Venizelos was elected chairman and then Prime Minister. All foreign troops left Crete, and Venizelos' government took full control.

Political Career in Greece

The Goudi Military Revolution of 1909

In May 1909, some Greek army officers, inspired by the Young Turks, wanted to reform the government and army. They formed the Military League. In August 1909, they camped in Goudi, Athens, and forced the government to resign. A new government was formed.

The League put pressure on the Parliament. But public support for the League quickly faded because the officers didn't know how to make their demands happen. The political problem continued until the League invited Venizelos from Crete to lead them.

Venizelos came to Athens. After talking with the Military League and politicians, he suggested a new government and changes to the Parliament. The King and Greek politicians thought his ideas were too risky. However, King George I feared things would get worse. He advised political leaders to accept Venizelos' ideas.

After some delays, the King agreed to let Stephanos Dragoumis (Venizelos' choice) form a new government. This government would hold elections after the League was disbanded. In the elections of August 8, 1910, almost half the seats in Parliament were won by new, independent politicians. Venizelos, even without campaigning, was at the top of the list in Attica. He was quickly recognized as the leader of the independents and founded the Komma Fileleftheron (Liberal Party).

Soon after, he called for new elections, hoping to win a clear majority. The old parties boycotted the election in protest. On December 11, 1910, Venizelos' party won 307 out of 362 seats. Most of the elected members were new to politics. Venizelos formed a government and began to reorganize Greece's economy, politics, and national affairs.

Reforms (1910–1914)

Venizelos worked to improve Greece's political and social systems, education, and literature. He tried to find practical solutions between different ideas. For example, in education, there was a debate about using the common spoken language, dimotiki. Conservatives preferred a more formal, "purified" language, katharevousa. The constitution (Article 107) ended up supporting the formal language.

On May 20, 1911, the Constitution was updated. It focused on making individual freedoms stronger. It also made it easier for Parliament to pass laws. It introduced mandatory elementary education and the right for the government to take private land for public use. It ensured civil servants had permanent jobs and allowed foreign experts to help reorganize the government and military. The goal was to make the country safer, ensure fair laws, and help the economy grow.

A new "Ministry of National Economy" was created in early 1911. It was led by Emmanuel Benakis, a rich Greek merchant and friend of Venizelos. Between 1911 and 1912, several laws were passed to start labor legislation in Greece. These laws banned child labor and night shifts for women. They also set working hours and Sunday holidays, and allowed for labor organizations. Venizelos also improved government management, justice, and security. He helped landless farmers in Thessaly get land.

Balkan Wars

Before the Wars

At this time, there were talks with the Ottoman Empire to improve life for Christians in Macedonia and Thrace, which were under Ottoman control. Many Balkan countries believed that if these reforms failed, the Ottoman Empire would have to leave the Balkans. Venizelos thought this was possible because the Ottoman Empire was weak and disorganized. Also, the Greek navy was strong in the Aegean Sea.

Venizelos wanted to wait until the Greek army and navy were stronger and the economy was better before starting any major actions. He suggested to the Ottoman Empire that Cretans should be allowed to send representatives to the Greek Parliament. This would solve the "Cretan Question." However, the Young Turks (who felt confident after the 1897 war) threatened to attack Athens if Greece insisted on these demands.

Forming the Balkan League

Venizelos saw that talks with the Turks were not working. He also did not want Greece to stay out of important events, as it had in the 1877 Russo-Turkish War. He decided that the only way to deal with the Ottoman Empire was to join other Balkan countries: Serbia, Bulgaria, and Montenegro. This alliance became known as the Balkan League.

Crown Prince Constantine went to Sofia to represent Greece at a royal event. In 1911, Bulgarian students were invited to Athens. These events helped relations. On May 30, 1912, Greece and Bulgaria signed a treaty promising to support each other if Turkey attacked. Venizelos also started talks with Serbia, leading to a friendship treaty in early 1913.

Montenegro started fighting the Ottoman Empire on October 8, 1912. On October 17, Greece and its Balkan allies declared war on the Ottoman Empire, joining the First Balkan War. On October 1, Venizelos announced the war to Parliament and accepted the Cretan representatives, finally uniting Crete with Greece. The Greek people were very excited about these events.

First Balkan War: Conflict with Prince Constantine

The First Balkan War caused problems between Venizelos and Crown Prince Constantine. Constantine was the Prince and future King, but he was also the army commander, reporting to the Ministry of Military Affairs, and thus to Venizelos. However, his father, King George, was the undisputed leader of the country. This made Venizelos' authority over Constantine less clear.

The Greek army began a successful march into Macedonia under Constantine's command. Soon, the first disagreement between Venizelos and Constantine appeared. It was about the army's goals. Constantine wanted to focus on defeating the Ottoman army, wherever it was. Venizelos was more practical. He wanted to free as many areas and cities as quickly as possible, especially Macedonia and Thessaloniki. He wanted the army to head east.

This disagreement became clear after the Greek army won the Battle of Sarantaporo. Venizelos stepped in and insisted that Thessaloniki, a major city and important port, must be captured. He said the army needed to turn east.

Venizelos kept in close contact with the King to stop Constantine from marching north. Even though the Greek army won the Battle of Giannitsa (west of Thessaloniki), Constantine hesitated to capture the city for a week. This led to an open conflict with Venizelos. Venizelos had information that the Bulgarian army was moving towards Thessaloniki. He sent a strong telegram to Constantine, holding him responsible if Thessaloniki was lost. This telegram and Constantine's reply are seen as the start of their conflict, which would lead to the National Schism during World War I.

Finally, on October 26, 1912, the Greek army entered Thessaloniki, just before the Bulgarians. But a new problem arose when Constantine allowed a small Bulgarian unit to enter the city. This unit soon became a full division and tried to share control of the city. Venizelos protested. Constantine asked him to take responsibility as prime minister and force them out. Venizelos felt that Constantine was trying to blame him for a problem Constantine had created. Most historians agree that Constantine did not understand the political importance of his decisions. These events increased their misunderstanding.

After the campaign in Macedonia, a large part of the Greek army, led by the Crown Prince, moved to Epirus. In the Battle of Bizani, the Ottomans were defeated, and Ioannina was taken on February 22, 1913. Meanwhile, the Greek navy quickly took over the Aegean islands still under Ottoman rule. The Greek fleet won two victories, gaining control of the Aegean Sea and preventing the Turks from sending more soldiers to the Balkans.

On November 20, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria signed a truce with Turkey. A conference was held in London, where Greece also took part. This conference led to the Treaty of London between the Balkan countries and Turkey. These talks showed Venizelos' diplomatic skill. During the negotiations, he built strong relations with the Serbs to counter Bulgarian demands. A Serbian-Greek military agreement was signed on June 1, 1913, promising mutual protection if Bulgaria attacked.

Second Balkan War

Despite all this, Bulgaria still wanted to be the main power in the Balkans. It made huge demands for territory. Serbia also wanted more land than originally agreed with Bulgaria. Serbia had lost northern Albania because the Great Powers decided to create the state of Albania. Bulgaria also claimed Thessaloniki and most of Macedonia. In the London conference, Venizelos rejected these claims. He pointed out that the Greek army had occupied Thessaloniki.

The disagreements between the allies were too big, and Bulgaria ended up fighting against Greece and Serbia. On May 19, 1913, Greece and Serbia signed an alliance pact in Thessaloniki. On June 19, the Second Balkan War began with a surprise Bulgarian attack on Serbian and Greek positions. Constantine, who was now King after his father's assassination in March, defeated the Bulgarian forces in Thessaloniki. He pushed the Bulgarian army back with many hard-won victories.

Bulgaria was overwhelmed by the Greek and Serbian armies. Meanwhile, Romania joined against Bulgaria, and the Romanian army marched towards Sofia. The Ottomans also took advantage and recaptured most of the land Bulgaria had taken. The Bulgarians asked for a truce. Venizelos went to the Greek headquarters to discuss Greece's land claims for the peace conference. Then he went to Bucharest, where a peace conference was held.

On June 28, 1913, a peace treaty was signed. Greece, Montenegro, Serbia, and Romania were on one side, and Bulgaria on the other. After two successful wars, Greece had doubled its territory. It gained most of Macedonia, Epirus, Crete, and the rest of the Aegean Islands. However, the status of the Aegean islands was still unclear, causing tension with the Ottomans.

World War I and Greece

Dispute Over Greece's Role

When World War I started and Austria-Hungary invaded Serbia, a big question arose: should Greece and Bulgaria join the war? Greece had a treaty with Serbia from the 1913 Bulgarian attack. However, King Constantine and his advisors argued that this treaty was only for Balkan conflicts and did not apply to Austria-Hungary.

The situation changed when the Allies offered Bulgaria parts of Serbia and Greek Eastern Macedonia (Kavala and Drama areas) if Bulgaria joined the Allies. Venizelos, who was promised land in Asia Minor if Greece joined, agreed to give the land to Bulgaria.

But King Constantine was strongly against Bulgaria and refused this deal. The two leaders disagreed. As a result, Bulgaria joined the Central Powers and invaded Serbia, leading to Serbia's defeat. Greece remained neutral.

King Constantine favored the Central Powers and wanted Greece to stay neutral. He believed in Germany's military strength. His German wife, Queen Sophia, and his pro-German court also influenced him. He tried to keep Greece neutral in a way that would help Germany and Austria.

In 1915, Winston Churchill suggested that Greece take action in the Dardanelles for the Allies. Venizelos saw this as a chance for Greece to join the Allies. However, the King and the Hellenic Army General Staff disagreed. Venizelos resigned on February 21, 1915. Venizelos' party won the next elections and formed a new government.

The National Schism

Even though Venizelos promised to stay neutral after the 1915 elections, he said that Bulgaria's attack on Serbia (with whom Greece had a treaty) forced him to change his policy. The Greek army began a small mobilization.

The disagreement between Venizelos and the King became very intense. The King used a constitutional rule that allowed him to dismiss a government. Meanwhile, in October 1915, the Allies landed an army in Thessaloniki, invited by Venizelos, to help Serbia. This action by Venizelos angered King Constantine.

The dispute continued. In December 1915, King Constantine forced Venizelos to resign a second time. He dissolved the Parliament, which was mostly controlled by Venizelos' party, and called for new elections. Venizelos left Athens and went back to Crete. He did not participate in the elections, believing the dissolution of Parliament was against the constitution.

On May 26, 1916, Fort Roupel in Macedonia was given up to German-Bulgarian forces by the royalist government. This caused a very bad impression. The Allies feared a secret alliance between the royalist government and the Central Powers. This would put their armies in Macedonia in danger. For Venizelos and his supporters, giving up Fort Rupel meant the start of the destruction of Greek Macedonia. Despite German promises, the Bulgarian forces started moving Greek people out of the area. By September 4, Kavala was occupied.

On August 16, 1916, during a rally in Athens, Venizelos publicly announced his complete disagreement with the King's policies. He had the support of the Allied army that had landed in Thessaloniki. This further divided the people into royalists (who supported the King) and Venizelists (who supported Venizelos). On August 30, 1916, Venizelist army officers organized a military coup in Thessaloniki. They declared a "Provisional Government of National Defence".

Venizelos, along with Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis and General Panagiotis Danglis, agreed to form this temporary government. On October 9, they moved to Thessaloniki and took command of the National Defence. Their goal was to oversee Greece's participation in the Allied war effort. These three men, known as the triumvirate, formed this government in direct opposition to the Athens government. They created a separate "provisional state" that included Northern Greece, Crete, and the Aegean Islands. These areas were the "New Lands" won during the Balkan Wars, where Venizelos had strong support. "Old Greece" was mostly pro-royalist. However, Venizelos declared, "we are not against the King, but against the Bulgarians." He did not want to end the monarchy. He kept trying to convince the King to join the Allies, blaming the King's "bad advisors" for his stance.

The National Defence government began forming an army for the Macedonian front. Soon, they were fighting against the Central Powers.

"Noemvriana" – Greece Enters World War I

In the months after the provisional government was created in Thessaloniki, talks between the Allies and the King became more intense. The Allies wanted the Greek army to reduce its size. They also wanted the military to leave Thessaly to keep their troops in Macedonia safe. This was a response to the royalist government giving up Fort Rupel.

The King, on the other hand, wanted promises that the Allies would not officially recognize Venizelos' government. He also wanted guarantees that Greece's independence and neutrality would be respected. He wanted a promise that any war materials given to the Allies would be returned after the war.

The French and British used Greek territory with Venizelos' government's help throughout 1916. This was opposed by royalists and increased Constantine's popularity. It also caused many anti-Allied protests in Athens. A growing movement in the army, led by officers like Ioannis Metaxas, was determined to resist disarming or giving war materials to the Allies.

The Allies continued to pressure the Athens government. On November 24, Admiral du Fournet gave a new ultimatum, demanding the immediate surrender of at least ten mountain batteries by December 1. The admiral tried one last time to convince the King to accept France's demands. He told the King that he would land Allied soldiers to occupy certain positions in Athens until his demands were met.

The King claimed that the army and people were pressuring him not to disarm. He refused to make any promises. However, he promised that Greek forces would not fire on the Allied soldiers. Despite how serious the situation was, both the royalist government and the Allies let events unfold. The royalist government decided to reject the admiral's demands on November 29. They organized armed resistance. By November 30, military units and royalist volunteers (over 20,000 men) gathered in and around Athens. They took strategic positions with orders not to fire unless fired upon. The Allied leaders, however, misjudged the situation. They believed the Greeks were bluffing and would give in easily.

The Allies landed a small group of soldiers in Athens on December 1, 1916. But they met organized resistance. An armed fight took place for a day until a compromise was reached. After the Allied soldiers left Athens the next day, a royalist mob attacked Venizelos' supporters for three days. This event became known as the "Noemvriana" in Greece. It created a deep divide between Venizelists and their opponents, making the National Schism even worse.

After the fighting in Athens, on December 2, 1916, Britain and France officially recognized Venizelos' government as the legal government. This effectively split Greece into two separate parts. On December 7, 1916, Venizelos' provisional government officially declared war on the Central Powers. In response, the King issued an order for Venizelos' arrest. The Archbishop of Athens, under pressure from the royal family, also condemned him.

The Allies did not want another failure. They decided to solve the problem by setting up a naval blockade around southern Greece, which was still loyal to the King. This caused extreme hardship for people in those areas. In June 1917, France and Great Britain decided to use their power as "protecting powers" (who had promised to guarantee a constitutional government for Greece) to demand the King's resignation. Constantine accepted and went into exile on June 15, 1917. He left his son Alexander on the throne, as the Allies wanted. His older son and crown prince, George, was not chosen. Many important royalists, especially army officers like Ioannis Metaxas, were also sent into exile in France and Italy.

These events cleared the way for Venizelos to return to Athens on May 29, 1917. Greece, now united, officially joined the war on the side of the Allies. The entire Greek army was then mobilized. Despite some tensions between supporters of the monarchy and Venizelos, the army began to participate in military operations against the Central Powers on the Macedonian front.

End of World War I

By the fall of 1918, the Greek army had 300,000 soldiers. It was the largest single group in the Allied army on the Macedonian front. The Greek army's presence changed the balance of power on the front. Under the command of French General Franchet d'Espèrey, a combined Greek, Serbian, French, and British force launched a major attack on September 14, 1918.

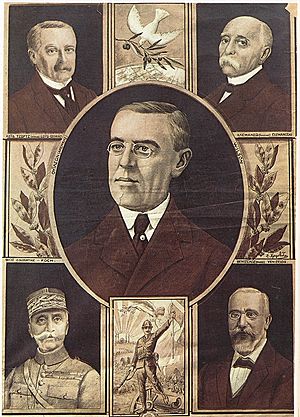

After heavy fighting (like the Battle of Skra), the Bulgarians gave up their defenses and started retreating. On September 24, the Bulgarian government asked for an armistice, which was signed five days later. The Allied army then pushed north and defeated the remaining German and Austrian forces. By October 1918, the Allied armies had recaptured all of Serbia and were preparing to invade Hungary. The attack stopped when the Hungarian leaders offered to surrender in November 1918, leading to the end of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The breakthrough on the Macedonian front was a key moment that helped end the war. Greece was given a seat at the Paris Peace Conference with Venizelos representing the country.

Treaty of Sèvres and Assassination Attempt

After World War I, Venizelos was Greece's main representative at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. He was away from Greece for almost two years. During this time, he became known as a very important international leader. President Woodrow Wilson reportedly said Venizelos was the most capable delegate in Paris.

In July 1919, Venizelos made an agreement with the Italians about the Dodecanese islands. He also secured more Greek land around Smyrna. The Treaty of Neuilly with Bulgaria (November 27, 1919) and the Treaty of Sèvres with the Ottoman Empire (August 10, 1920) were huge successes for both Venizelos and Greece. Because of these treaties, Greece gained Western Thrace, Eastern Thrace, Smyrna, and the Aegean islands of Imvros and Tenedos, and the Dodecanese (except Rhodes).

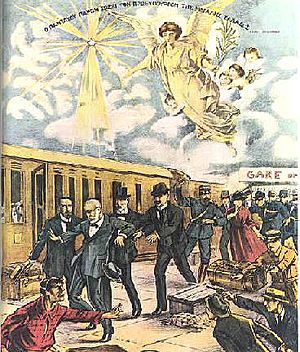

Despite these achievements, strong disagreements continued between political groups. On his way home on August 12, 1920, Venizelos survived an assassination attempt by two royalist soldiers at the Gare de Lyon railway station in Paris. This event caused unrest in Greece. Venizelos' supporters attacked known anti-Venizelists. The persecution of Venizelos' opponents reached a peak with the killing of the anti-Venizelist Ion Dragoumis by Venizelist paramilitary groups on August 13. After recovering, Venizelos returned to Greece. He was welcomed as a hero because he had freed areas with Greek populations and created a larger state.

1920 Election Loss and Exile

King Alexander of Greece died from blood poisoning after a monkey bite on October 25, 1920, two months after the treaty was signed. His death brought back the question of whether Greece should be a monarchy (ruled by a king) or a republic (ruled by elected officials). The November elections became a contest between Venizelos and the return of the exiled King Constantine I of Greece, Alexander's father.

In the elections, anti-Venizelists, mostly supporters of Constantine, won 246 out of 370 seats. This defeat surprised many. Venizelos himself did not even get elected as a Member of Parliament. He believed this happened because the Greek people were tired of war, having been fighting almost constantly since 1912. Venizelists thought that promises of ending the war and leaving Asia Minor were the opposition's strongest weapons. Also, Venizelists had misused their power between 1917 and 1920 and had prosecuted their opponents. This also made people vote for the opposition. So, on December 6, 1920, King Constantine was called back by a public vote. This made the newly freed populations in Asia Minor very unhappy. The Great Powers also opposed Constantine's return. Because of his defeat, Venizelos left for Paris and stopped being involved in politics.

Once the anti-Venizelists came to power, they decided to continue the campaign in Asia Minor. However, they dismissed experienced pro-Venizelist military officers for political reasons. They also underestimated the Turkish army. This affected the war's outcome. Italy and France used the King's return as an excuse to make peace with Mustafa Kemal, the Turkish leader. By April 1921, all Great Powers had declared their neutrality. Greece was alone in continuing the war.

Mustafa Kemal launched a massive attack on August 26, 1922. The Greek forces were defeated and retreated to Smyrna, which soon fell to the Turks on September 8, 1922 (see Great Fire of Smyrna).

After the Greek army's defeat by the Turks in 1922, an armed uprising led by Colonels Nikolaos Plastiras and Stylianos Gonatas took place. King Constantine was removed from the throne and replaced by his eldest son, George. Six royalist leaders were executed. Venizelos then led the Greek team that negotiated peace with the Turks. He signed the Treaty of Lausanne with Turkey on July 24, 1923. This treaty meant that over a million Greeks (Christians) were forced to leave Turkey. In exchange, over 500,000 Turks (Muslims) were forced to leave Greece. Greece also had to give up claims to eastern Thrace, Imbros, and Tenedos to Turkey.

After a failed pro-royalist uprising, King George II of Greece was forced into exile. Venizelos returned to Greece and served as prime minister until 1924. Disagreements with anti-monarchists forced him back into exile.

During his time away from power, he translated Thucydides into modern Greek. This translation was published in 1940, after his death.

Return to Power (1928–32)

In the elections held on July 5, 1928, Venizelos' party won power again. They forced the government to hold new elections on August 19 of the same year. This time, his party won 228 out of 250 seats in Parliament. During this time, Venizelos tried to end Greece's isolation by improving relations with its neighbors. He succeeded with the newly formed Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Italy.

First, Venizelos signed an agreement with Benito Mussolini in Rome on September 23, 1928. Then, he started talks with Yugoslavia, which led to a Treaty of Friendship signed on March 27, 1929. An additional agreement settled the status of the Yugoslav free trade zone of Thessaloniki in a way that helped Greece. However, despite British efforts, full peace with Bulgaria was not achieved during his time as prime minister. Venizelos was also careful with Albania. Although relations were good, no major steps were taken to solve issues, mainly concerning the Greek minority in South Albania.

Venizelos' biggest success in foreign policy during this period was making peace with Turkey. He had expressed his wish to improve Greek–Turkish relations even before his election victory. Eleven days after forming his government, he sent letters to the prime minister and foreign minister of Turkey, saying that Greece had no claims on their country's land. Turkey's response was positive, and Italy was eager to help the two countries agree.

However, talks stalled because of the complicated issue of properties belonging to the exchanged populations. Finally, the two sides reached an agreement on April 30, 1930. On October 25, Venizelos visited Turkey and signed a treaty of friendship. Venizelos even nominated Atatürk for the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize, showing the mutual respect between the two leaders. The German Chancellor Hermann Müller called the Greek-Turkish peace the "greatest achievement seen in Europe since the end of the Great War." However, Venizelos' actions were criticized in Greece, even by members of his own party who represented Greek refugees from Turkey. They accused him of giving up too much on naval weapons and the properties of Greeks who were forced to leave Turkey.

In 1929, Venizelos' government introduced a law called the Idionymon. This law limited civil liberties and started to repress unionism, left-wing supporters, and communists. This was done to avoid reactions from lower-income groups whose conditions had worsened due to immigration.

His position in Greece weakened because of the Great Depression in the early 1930s. In the 1932 elections, he was defeated by the People's Party led by Panagis Tsaldaris. The political atmosphere became more tense. In 1933, Venizelos was the target of a second assassination attempt. The new government's pro-royalist views led to two attempts by General Nikolaos Plastiras to overthrow the government: one in 1933 and another in 1935. The failure of the second coup was very important for the future of the Second Hellenic Republic. After the coup failed, Venizelos left Greece again. In Greece, trials and executions of important Venizelists took place, and he himself was sentenced to death in his absence. The weakened Republic was ended by another coup in October 1935, led by General Georgios Kondylis. George II returned to the throne after a rigged referendum in November.

Death

Venizelos went to Paris. On March 12, 1936, he wrote his last letter to Alexandros Zannas. He had a stroke on the morning of March 13 and died five days later in his apartment in Paris. His body was taken by the destroyer Pavlos Kountouriotis to Chania, avoiding Athens to prevent unrest. A large public ceremony accompanied his burial at Akrotiri, Crete.

Legacy

One of Venizelos' most important contributions to Greek politics was creating the Liberal Party in 1910. This was different from earlier Greek parties, which were often based on foreign powers or a single political leader. The Liberal Party was built around Venizelos' ideas, and it continued even after his death.

The creation of a leading party also led to the birth of an opposing party. This opposing party was linked to the King, but it also continued even when the monarchy was abolished. Venizelism was a liberal movement that opposed the royalist and conservative ideas. These two groups competed for power throughout the period between the two World Wars.

The main ideas of Venizelism, inspired by Venizelos, included:

- Opposing the monarchy.

- Supporting the Megali Idea (the dream of a larger Greece).

- Forming alliances with Western democratic countries, especially the United Kingdom and France, against Germany during the World Wars. Later, it supported alliances with the United States against the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

- Having an economic policy that protected local industries.

Themistoklis Sofoulis became the leader of the Liberal Party after Venizelos in the 1920s. The party survived many challenges. In 1950, Venizelos' son, Sophoklis Venizelos, became the head of the Liberal Party. Later, the Center Union (Enosis Kendrou), founded in 1961 by Georgios Papandreou, became the ideological successor of the Liberal Party. The Center Union eventually faded, replaced by the Panhellenic Socialist Movement of Andreas Papandreou in the late 1970s.

Venizelos was one of the few Greek politicians who became famous worldwide during his lifetime. Between 1915 and 1921, five biographies about him were published in English, along with many newspaper articles. The character of Constantine Karolides, the smart and charming prime minister of Greece in John Buchan's 1915 spy novel The Thirty-Nine Steps, is based on Venizelos. Venizelos' efforts to create an alliance of Balkan states made the press, especially in Britain, see him as a wise leader who brought peace and stability to the Balkans.

Athens International Airport is named after Venizelos.

Personal Life and Family

In December 1891, Venizelos married Maria Katelouzou. They lived in the upper floor of a house in Chalepa. His mother, brother, and sisters lived on the ground floor. They had two children: Kyriakos Venizelos in 1892 and Sophoklis Venizelos in 1894. Their marriage was short and sad. Maria died in November 1894 after the birth of their second child. Her death deeply affected Venizelos. As a sign of mourning, he grew his famous beard and mustache, which he kept for the rest of his life.

After losing the November 1920 elections, he went into exile in Nice and Paris. In September 1921, twenty-seven years after Maria's death, he married Helena Schilizzi in London. Police advised them to be careful of assassination attempts. They had a private religious ceremony at Witanhurst, the home of a family friend. There, Venizelos met important figures like Arthur Balfour and David Lloyd George.

The couple settled in an apartment in Paris. He lived there until 1927 when he returned to Chania.

Venizelos/Mitsotakis family tree

| Main members of the Venizelos/Mitsotakis/Bakoyannis family. Prime Ministers of Greece are highlighted in light blue. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Images for kids

-

Venizelos' father's shop in Chania.

-

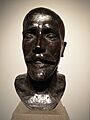

A statue in Thessaloniki (sculpted by Giannis Pappas).

See also

In Spanish: Eleftherios Venizelos para niños

In Spanish: Eleftherios Venizelos para niños