Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920) facts for kids

The Paris Peace Conference was a very important meeting held in 1919 and 1920. It happened after World War I ended. The countries that won the war, called the Allies, met to decide the peace terms for the countries that lost, known as the Central Powers.

Leaders from Britain, France, the United States, and Italy were the most powerful at this conference. They created five treaties that changed the maps of Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Pacific Islands. They also made the losing countries pay a lot of money. Germany and the other defeated nations were not allowed to speak or give their opinions. This made them feel angry and resentful for many years.

Diplomats from 32 different countries and groups attended the conference. The main things they decided were to create the League of Nations, sign five peace treaties, and divide up Germany's and the Ottoman Empire's overseas lands as "mandates" (like territories managed by other countries), mostly given to Britain and France. They also made Germany pay for the war's damage (called reparations) and drew new country borders. These new borders sometimes involved plebiscites (votes by the people) to better match where different ethnic groups lived.

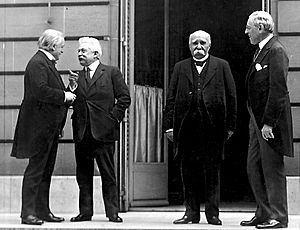

The most important treaty was the Treaty of Versailles with Germany. A part of this treaty, Article 231, said that Germany and its allies were entirely to blame for the war. This was very humiliating for Germany. It also set the stage for huge payments Germany was supposed to make, though it only paid a small part before payments stopped in 1931. The "Big Four" leaders were Georges Clemenceau (France), David Lloyd George (Britain), Woodrow Wilson (United States), and Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (Italy). They met many times and made all the big decisions before they were officially approved.

The conference started on January 18, 1919. Even though the main leaders finished their work in June 1919, the official peace process didn't truly end until July 1923, when the Treaty of Lausanne was signed. People often call it the "Versailles Conference" because the first treaty was signed at the historic Palace of Versailles. However, most of the talks happened in Paris at the Quai d'Orsay.

Contents

Key Decisions and Treaties

The conference officially started on January 18, 1919, in Paris. This date was chosen because it was the anniversary of William I becoming German Emperor in 1871. That happened in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, right after the Siege of Paris.

Delegates from 27 nations worked in 52 different groups. They held 1,646 meetings to prepare reports on many topics. These topics ranged from prisoners of war to undersea cables and even international aviation. Their main recommendations were included in the Treaty of Versailles with Germany, which had 15 chapters and 440 rules. Treaties for the other defeated nations were also created.

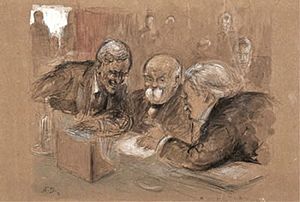

The five main powers were France, Britain, Italy, the U.S., and Japan. Japan played a smaller role, so the "Big Four" leaders truly ran the conference. They met informally 145 times and made all the major decisions. The other delegations then approved these decisions in open meetings. The conference ended on January 21, 1920, when the League of Nations held its first meeting.

Five major peace treaties came out of the Paris Peace Conference:

- The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, with Germany.

- The Treaty of Saint-Germain, signed on September 10, 1919, with Austria.

- The Treaty of Neuilly, signed on November 27, 1919, with Bulgaria.

- The Treaty of Trianon, signed on June 4, 1920, with Hungary.

- The Treaty of Sèvres, signed on August 10, 1920, with the Ottoman Empire. This treaty was later changed by the Treaty of Lausanne on July 24, 1923, with the Republic of Turkey.

The main outcomes were the creation of the League of Nations, the five peace treaties, and the division of German and Ottoman lands into "mandates." Germany also had to pay reparations, and new national borders were drawn. The Treaty of Versailles blamed Germany for the war, which was very humiliating and led to huge reparation demands.

Because the "Big Four" made most decisions, Paris became like a center of world government during the conference. The Treaty of Versailles greatly weakened Germany's military and blamed Germany entirely for the war. This caused anger and resentment in Germany, which some historians believe helped the Nazi Party gain power and contributed to World War II. The League of Nations was controversial in the United States. Critics said it would take away the US Congress's power to declare war. So, the U.S. Senate never approved the peace treaties, and the United States never joined the League.

Dividing Colonial Lands: Mandates

A big topic at the conference was what to do with Germany's overseas colonies. Austria-Hungary didn't have many colonies, and the Ottoman Empire was handled separately.

The British dominions (like Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa) wanted rewards for their help in the war. Australia wanted New Guinea, New Zealand wanted Samoa, and South Africa wanted South West Africa. President Wilson wanted the League of Nations to manage all German colonies until they could become independent.

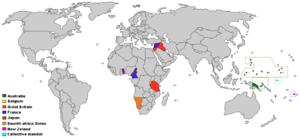

British Prime Minister Lloyd George suggested a compromise: three types of mandates. Mandates for the Turkish areas would be split between Britain and France. New Guinea, Samoa, and South West Africa were close to Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, so these countries would manage them. Finally, the African colonies needed careful supervision as "Class B" mandates, which Britain, France, and Belgium would provide. Italy and Portugal also received small areas. Wilson and the others eventually agreed. Japan got mandates over German lands north of the Equator.

Wilson didn't want any mandates for the United States. He had some strong disagreements with Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes. Wilson once said to Hughes, "But after all, you speak for only five million people." Hughes famously replied, "I represent sixty thousand dead."

Britain's Goals

The British delegates mainly wanted to keep the British Empire strong and safe. They also had specific goals:

- Make sure France was safe from future attacks.

- Remove the threat of the German High Seas Fleet (Germany's navy).

- Settle disagreements over land.

- Support the new League of Nations.

Japan's idea for racial equality didn't directly conflict with Britain's interests at first. However, it became a big problem because of how it might affect immigration to British dominions, especially Australia. Britain decided to drop its support for the racial equality proposal to keep Australia happy and maintain the empire's unity.

Britain also didn't allow representatives from the newly declared Irish Republic to present their case for independence at the conference. Irish nationalists were not popular with the Allies in 1919 because they had opposed the war.

David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, joked that he did "not do badly" at the conference, "considering I was seated between Jesus Christ and Napoleon." He was referring to Wilson's strong desire for a gentle peace with Germany and Clemenceau's firm demand for Germany to be punished.

Dominion Representation

At first, the British dominions were not invited separately. They were expected to send representatives as part of the British team. However, Canada's Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, insisted that Canada should have its own seat. He argued that Canada had lost nearly 60,000 soldiers, more than the 50,000 American soldiers lost. Lloyd George eventually agreed, and Canada, India, Australia, Newfoundland, New Zealand, and South Africa got their own seats at the conference and in the League of Nations.

Canada, despite its huge losses, did not ask for money or mandates. The Australian delegation, led by Prime Minister Billy Hughes, strongly pushed for reparations, control of German New Guinea, and the rejection of the Racial Equality Proposal. Hughes was worried about Japan's growing power.

France's Goals

French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau led his country's delegation. His main goal was to make Germany much weaker in military, strategy, and economy. He had seen Germany attack France twice in 40 years and was determined to prevent it from happening again. Clemenceau especially wanted the U.S. and Britain to promise to protect France if Germany attacked again.

Clemenceau was also doubtful about Wilson's Fourteen Points. He famously complained, "Mr. Wilson bores me with his fourteen points. Why, God Almighty has only ten!" Wilson did sign a defense treaty with France, but the U.S. Senate never approved it, so it never took effect.

Some French officials also considered trying to make friends with Germany. In May 1919, a diplomat named René Massigli secretly went to Berlin. He offered to change parts of the peace treaty. Massigli suggested that France and Germany should work together and warned that fighting between them would only benefit the "Anglo-Saxon powers" (the U.S. and Britain). However, the Germans rejected these offers, thinking it was a trick. They also believed the United States would be more likely to make the treaty less harsh than France. In the end, it was Lloyd George who pushed for better terms for Germany.

Italy's Goals

In 1914, Italy stayed neutral even though it was allied with Germany and Austria-Hungary. In 1915, Italy joined the Allies. They did this to gain territories promised in a secret agreement called the Treaty of London. These lands included Trentino, Tyrol up to Brenner, Trieste, Istria, most of the Dalmatian Coast, Valona, and a protectorate over Albania.

Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando tried to get all these promised lands. Italy had lost 700,000 soldiers and spent a lot of money, so both the government and the people felt they deserved these territories and even more, like Fiume. Orlando, who couldn't speak English, worked with his Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino.

At the conference, Italy gained Istria, Trieste, Trentino, and South Tyrol. However, most of Dalmatia went to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and Fiume remained a disputed area. This caused great anger among Italian nationalists. Orlando also secured Italy's permanent membership in the League of Nations and promises for some African territories. But nationalists felt the war was a "mutilated victory" because Italy didn't get everything it wanted. Orlando was eventually forced to leave the conference and resign.

This disappointment in Italy was used by nationalists and fascists to claim that Italy had been betrayed. This helped lead to the rise of Italian fascism.

Japan's Goals

Japan sent a large group, led by former Prime Minister Marquis Saionji Kinmochi. Japan was one of the "big five" powers but didn't care much about European issues. Instead, Japan focused on two main demands:

- Including a racial equality clause in the League of Nations agreement.

- Gaining control of former German colonies: Shantung (including Kiaochow) and Pacific islands north of the Equator (like the Marshall Islands and Carolines).

The Japanese delegation became unhappy when they only received half of what they wanted from Germany's former rights. They then left the conference.

Racial Equality Proposal

On February 13, the leader of the Japanese delegation, Saionji Kinmochi, suggested adding a "racial equality clause" to the Covenant of the League of Nations. This clause stated that all nations in the League should treat all foreign citizens equally, without distinction based on their race or nationality.

This idea caused problems for the American and British teams. While it fit Britain's general idea of equality for all British subjects, it strongly conflicted with the views of its dominions, especially Australia and South Africa. These dominions were against the clause and pressured Britain to oppose it. Britain eventually gave in to this pressure and did not vote for the clause. President Wilson was neutral about the clause, but there was strong public opposition in America. He ruled that the proposal needed a unanimous vote to pass. In the end, only 11 of 17 delegates voted for it, so it failed. This failure influenced Japan to turn away from working with Western countries and towards more nationalist and militarist policies.

Territorial Claims

Japan's claim to Shantung faced strong opposition from Chinese student groups. In 1914, Japan had taken control of this territory from Germany. Japan had also secretly agreed with Britain, France, and Italy in 1917 that it would keep these territories. Despite American support for China, Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles gave the German concessions in China to Japan instead of returning them to China. The Chinese delegation refused to sign the treaty because of this. Chinese anger led to protests known as the May Fourth Movement. The Pacific Islands north of the equator became a mandate managed by Japan.

America's Goals

Before President Wilson arrived in Europe in December 1918, no sitting American president had ever visited the continent. Wilson's Fourteen Points, announced in 1917, had gained a lot of support as the war ended. Wilson felt it was his duty to be a key figure in the peace talks. People had high hopes that he would deliver what he had promised for the world after the war.

However, once Wilson arrived, he found "rivalries, and conflicting claims." He mostly tried to influence France and Britain, led by Clemenceau and Lloyd George, regarding Germany and the former Ottoman Empire. Wilson's efforts to get his Fourteen Points accepted mostly failed because France and Britain refused to adopt some of his key ideas.

In Europe, several of his Fourteen Points clashed with what other powers wanted. The United States did not believe that Germany alone should be blamed for the war, as Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles stated. It wasn't until 1921, under U.S. President Warren Harding, that the United States finally signed separate peace treaties with Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

In the Middle East, talks were complicated by many different goals and claims. The United States hoped to create a more liberal and diplomatic world, as outlined in the Fourteen Points, where democracy and self-determination would be respected. France and Britain, however, already had large empires and wanted to remain powerful colonial nations.

France and Britain tried to please Wilson by agreeing to create his League of Nations. However, many Americans wanted the U.S. to stay out of international affairs. Also, some parts of the League's rules conflicted with the US Constitution. Because of this, the United States never approved the Treaty of Versailles or joined the League of Nations, which Wilson had helped create to promote peace through diplomacy.

Other Nations' Approaches

Baltic States

Delegations from the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania also attended the conference. They successfully gained international recognition for their independence.

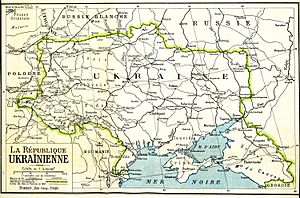

Ukraine

Ukraine had its best chance to gain recognition and support from foreign powers at the conference. However, the Allies largely ignored Ukraine. British Prime Minister Lloyd George called the Ukrainian leader an adventurer. The British government was unsure whether to support a united or divided Russia. The United States wanted a strong, united Russia to balance Japan's power. Ukraine was effectively ignored.

Belarus

A delegation from the Belarusian Democratic Republic also participated. They tried to gain international recognition for Belarus's independence.

Minority Rights

At Wilson's insistence, the "Big Four" required Poland to sign a treaty on June 28, 1919. This treaty guaranteed minority rights for groups like Germans, Jews, and Ukrainians in the new nation. Poland signed under protest and didn't do much to enforce these rights. Similar treaties were signed by Czechoslovakia, Romania, Yugoslavia, Greece, Austria, Hungary, and Bulgaria.

These treaties meant that the new country had to protect the life and liberty of all people, regardless of their background, nationality, language, race, or religion. Freedom of religion was guaranteed. The treaty also ensured basic civil, political, and cultural rights, stating that all citizens should be equal before the law. While Polish was the national language, the treaty allowed minority languages to be used freely in private, business, religion, and public meetings. Minorities could also set up their own charities, churches, and schools.

Caucasus

The three South Caucasian republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia all sent groups to the conference. They tried to get protection from the ongoing Russian Civil War. However, none of the major powers wanted to take control of these areas. After many delays, these three countries eventually gained official recognition from the Allied powers. The Allied leaders decided to only provide arms, supplies, and food to these republics.

Korea

A group of Koreans from China and Hawaii, including a representative from the Korean Provisional Government, made it to Paris. They were helped by the Chinese, who wanted to embarrass Japan. However, no nation at the conference took the Koreans seriously because Korea was already a Japanese colony. The failure of Korean nationalists to get support ended their hopes for foreign help.

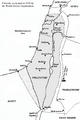

Palestine

After the conference decided to separate the Arab areas from the Ottoman Empire and apply the new mandate system, the World Zionist Organization presented its plans. They wanted recognition of Jewish rights to the land, clear borders, and for the League of Nations to oversee it under a British mandate. A follow-up conference in San Remo in 1920 led to the creation of the Mandate for Palestine, which started in 1923.

Assyrians

Many Assyrians had died during the Assyrian genocide before the conference. Several Assyrian groups came to the conference hoping for a free Assyria. They came from different parts of the world, but their wishes for self-rule were not recognized.

Aromanians

A group of Aromanians also participated in the Peace Conference. They wanted their people to have self-rule, similar to an earlier attempt to create the Principality of the Pindus. However, they failed to get any recognition for their desires.

Women's Influence

An unusual part of the conference was the strong pressure from a committee of women. They wanted to establish women's basic social, economic, and political rights, like the right to vote, within the new peace agreements. Even though they weren't given official seats, the leader, Marguerite de Witt-Schlumberger, organized an Inter-Allied Women's Conference (IAWC). This group met from February to April 1919.

The IAWC pushed President Wilson and other delegates to allow women into the conference's committees. They succeeded in getting a hearing from the commissions dealing with international labor and the League of Nations. A key result of the IAWC's work was Article 7 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. It stated: "All positions under or in connection with the League, including the Secretariat, shall be open equally to men and women." More generally, the IAWC made women's rights a central issue in the new world order created in Paris.

Historical Views

The way the world map was redrawn at the conference created many problems that would later contribute to World War II. Historian Eric Hobsbawm said that no other attempt had been made to divide Europe into countries based on single ethnic and language groups. He argued that this idea could lead to the forced removal or killing of minorities, which was sadly shown in the 1940s.

Some historians, like Hobsbawm, believe that Wilson's Fourteen Points, especially the idea of self-determination, were meant to stop the spread of communism after the Russian Revolution. They thought that creating many small nation-states would act as a "quarantine belt" against the "Red virus."

Historian Antony Lentin saw Lloyd George's role in Paris as a big success. He was a skilled negotiator who used charm, cleverness, and determination. While he understood France's desire to control Germany, he also worked to prevent France from becoming too powerful. He helped include the "war-guilt clause" and tried to keep a balanced view of the postwar world.

Images for kids

- Commission of Responsibilities

- Congress of Vienna

- Czech Corridor

- Reparation Commission

- The Inquiry

- Minority Treaties

- Congress of Oppressed Nationalities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

See also

In Spanish: Conferencia de Paz de París (1919) para niños

In Spanish: Conferencia de Paz de París (1919) para niños