History of modern Greece facts for kids

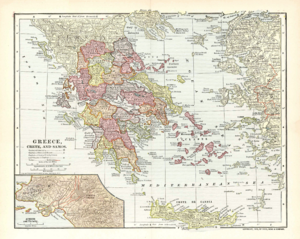

The history of modern Greece tells the story of Greece from when it became an independent country in 1828 until today. Powerful nations like Britain, France, and Russia helped Greece gain freedom from the Ottoman Empire.

Contents

- How Greece Became Independent

- Ioannis Kapodistrias: Greece's First Leader

- The First King of Greece

- King George I and a Growing Greece (1864–1913)

- World War I and Big Changes (1914-1922)

- Republic and Monarchy (1922–1940)

- Greece in World War II

- Greek Civil War (1944–1949)

- Postwar Greece (1950–1973)

- Transition to Democracy (1973–2009)

- Greece's Economic Challenges (2009–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

How Greece Became Independent

For a long time, the Byzantine Empire ruled most Greek-speaking lands. But after many invasions and a big attack on Constantinople in 1204, the empire became weak. Most of Greece slowly came under the control of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Some parts of Greece, like the Ionian Islands, stayed free from Ottoman rule, often controlled by Venice. In the mountains, many Greeks found refuge and kept their traditions alive.

A big uprising against the Ottomans happened in the 1770s, but it was put down. However, around this time, new ideas about freedom and nationhood spread in Greece. Greeks who studied in Europe brought back modern thoughts, and Greek merchants became wealthy.

In 1821, Greeks started a major war for independence against the Ottoman Empire. Even with some internal disagreements, the fight continued. This led the Great Powers (Britain, Russia, and France) to step in. They recognized the Greek rebels' right to have their own state.

Greece was first meant to be a self-governing state under the Ottomans. But by 1832, it was recognized as a fully independent kingdom. During this time, Ioannis Kapodistrias, a former Russian foreign minister, was chosen to lead the new Greek state in 1827.

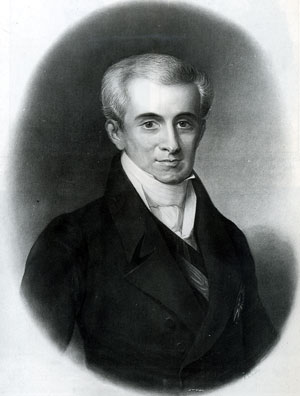

Ioannis Kapodistrias: Greece's First Leader

When Kapodistrias arrived, he started many important changes to modernize Greece. He brought peace after a civil war and reorganized the army. He also set up the first modern health system, which helped control diseases like typhoid fever.

Kapodistrias worked with other countries to set Greece's borders and its level of independence. He signed the peace treaty that ended the War of Independence. He also introduced the phoenix, Greece's first modern money, and organized local government. To help people, he even brought the potato to Greece for farming!

However, Kapodistrias tried to reduce the power of old, powerful families who had led the revolution. These families, called capetanei, expected to have a big role in the new government. When a conflict broke out in Laconia, he called in Russian troops to restore order.

Some people, especially rich merchants, grew to dislike Kapodistrias's rule. They felt he was acting too much like a dictator and not calling a National Assembly. In 1831, some rebels seized part of the Greek navy. Kapodistrias asked for British and French help, but they refused. Russian ships helped put down the rebellion, but some of Greece's best ships were destroyed. This weakened Kapodistrias's position and led to his downfall.

The First King of Greece

In 1831, Kapodistrias ordered the arrest of Petros Mavromichalis, a powerful leader from the Mani region. This deeply offended the Mavromichalis family. On October 9, 1831, Kapodistrias was assassinated by Petros's brother and son on the steps of a church in Nafplio.

His younger brother, Augustinos Kapodistrias, took over but only for six months. During this time, Greece was in chaos. In 1832, other European powers decided that Greece would be an independent kingdom. They chose Otto of Bavaria, a young German prince, to be the first King of Greece.

King Otto's Rule (1833–1863)

King Otto's rule was difficult. At first, Bavarian regents ruled for him, which made them unpopular because they tried to impose German ways and kept Greeks out of important government jobs. However, they did help set up Greece's administration, army, justice, and education systems.

Otto became king in his own right in 1835. He wanted to govern Greece well, but he faced challenges. He was Roman Catholic, so he couldn't be crowned under the Orthodox faith. Also, he had no children, meaning he couldn't start a royal family line.

Greeks became unhappy with the continued Bavarian influence. In 1843, a revolution broke out in Athens. Otto agreed to grant a constitution and create a parliament with two houses. This gave more power to Greek politicians, many of whom had fought in the War of Independence.

During the 19th century, Greek politics focused on the "national question." Many Greeks still lived under Ottoman rule. The dream was to free all Greek lands and create a larger state with Constantinople as its capital. This dream was called the Great Idea (Megali Idea).

In 1854, during the Crimean War, Greece tried to gain Ottoman territory with large Greek populations. Greece invaded Thessaly and Epirus. But Britain and France occupied Greece's main port, Piraeus, to stop further moves. The revolts failed, and Greece gained nothing.

A new generation of politicians grew tired of King Otto's interference. In 1862, the King dismissed his prime minister, leading to a military rebellion. Otto was forced to leave the country.

The Greeks then asked Britain for Prince Alfred to be their new king, but this was not allowed. Instead, a young Danish prince became King George I. He was a popular choice and agreed that his children would be raised Greek Orthodox. As a reward, Britain gave the Ionian Islands to Greece.

King George I and a Growing Greece (1864–1913)

With encouragement from Britain and King George, Greece adopted a more democratic constitution in 1864. The King's powers were reduced, and all adult men could vote. Greek politics, however, remained influenced by powerful families.

Two main political groups emerged: liberals, led by Charilaos Trikoupis, and conservatives, led by Theodoros Deligiannis. Trikoupis wanted to work with Britain, build infrastructure, and develop industries. Deligiannis focused on Greek nationalism and the Megali Idea.

Greece remained a very poor country. It lacked raw materials and capital. Farming was mostly for survival, and main exports were currants and tobacco. Some Greeks became rich as merchants and shipowners, but this wealth didn't reach most farmers. Greece was heavily in debt to foreign banks.

By the 1890s, Greece was almost bankrupt. Many people moved to the United States to find work. Despite this, there was progress in building roads and public buildings in Athens. The city even hosted the first modern Olympic Games in 1896, which was a big success.

A big issue in 19th-century Greece was the language. Most Greeks spoke a form called Demotic. But educated people wanted to use Katharevousa, a "purified" form closer to Ancient Greek, which most ordinary Greeks couldn't understand. This caused arguments and even riots.

Greeks were united in their desire to free Greek-speaking areas still under Ottoman rule, especially Crete. In 1881, parts of Thessaly and Epirus were given to Greece.

In 1897, Greece declared war on the Ottomans due to popular pressure. The Greek army was defeated, but the Great Powers intervened. Greece lost little territory, and Crete became a self-governing state.

Nationalist feelings grew among Greeks in the Ottoman Empire. In Macedonia, Greeks competed with Bulgarians for influence. In 1908, the Young Turk Revolution happened in the Ottoman Empire. Taking advantage, Austria-Hungary took over Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Bulgaria declared independence. On Crete, a young politician named Eleftherios Venizelos declared union with Greece.

Many Greeks, especially young military officers, were upset that their government couldn't bring Crete into Greece. They formed a secret society, the "Military League," to push for reforms.

The Goudi coup in 1909 was a turning point. The military leaders asked Venizelos to come to Greece as their political advisor. Venizelos quickly became a powerful figure. He became prime minister in 1910, and his influence shaped Greek politics for the next 25 years.

Venizelos started a major reform program, including a new, more liberal constitution. He invited French and British military experts to train the army and navy.

Balkan Wars: Expanding Greece

In 1912, Christian Balkan states (Greece, Bulgaria, Montenegro, and Serbia) formed the Balkan League and declared war on the Ottoman Empire. In the First Balkan War, the Ottomans were defeated. The Greeks captured Thessaloniki just before the Bulgarians and also took much of Epirus, Crete, and the Aegean Islands.

The war ended in 1913, but the allies soon fought over how to divide Macedonia. In June 1913, Bulgaria attacked Greece and Serbia, starting the Second Balkan War. Bulgaria was defeated. The peace treaty left Greece with southern Epirus, southern Macedonia, Crete, and most Aegean islands. These gains nearly doubled Greece's size and population.

In March 1913, King George was assassinated. His son became King Constantine I. Constantine was the first Greek king born in Greece and the first to be Greek Orthodox. He was very popular as a military commander, almost as popular as Venizelos.

World War I and Big Changes (1914-1922)

When World War I started in 1914, King Constantine and Prime Minister Venizelos disagreed on what Greece should do. Constantine, who had German ties, wanted to stay neutral. Venizelos, who liked Britain, wanted Greece to join the Allies.

Greece, being a sea nation, couldn't go against the strong British navy. King Constantine favored neutrality, saying Greece needed a break after two wars. Venizelos wanted Greece to join the Allies. Venizelos resigned but won the 1915 elections and formed a new government. When Bulgaria joined Germany in the war, Venizelos invited Allied forces into Greece. Constantine dismissed him again.

In 1916, Venizelist officers in Allied-controlled Thessaloniki formed a separate government. Constantine ruled only "Old Greece." His government faced humiliations from the Allies. In November 1916, the French occupied Piraeus and forced the Greek fleet to surrender. There were also riots against Venizelos's supporters in Athens.

In June 1917, King Constantine was forced to leave the country. His second son, Alexander, became King. Venizelos now led a united Greece into the war on the Allied side. But Greek society was deeply divided between Venizelists and anti-Venizelists, a split called the National Schism.

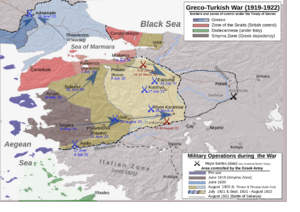

War with Turkey (1919–1922)

After World War I ended in 1918, the Ottoman Empire was ready to be divided. Greece expected the Allies to keep their promises. Thanks to Venizelos's efforts, Greece gained Western Thrace in 1919 and Eastern Thrace and a zone around Smyrna in western Anatolia in 1920.

At the same time, a Turkish national movement rose in Turkey, led by Mustafa Kemal. He set up a rival government and fought the Greek army.

It seemed the Megali Idea was close to coming true. But the deep divisions in Greece continued. An assassination attempt was made on Venizelos. Even more surprisingly, Venizelos's party lost the 1920 elections. Greeks voted for King Constantine to return from exile after King Alexander's sudden death.

The new government, which had promised to end the war in Anatolia, instead intensified it. But the return of King Constantine had bad results. Many experienced Venizelist officers were dismissed. Italy and France used Constantine's return as an excuse to support Kemal. In August 1922, the Turkish army defeated the Greek front and took Smyrna, leading to a terrible fire.

The Greek army had to leave Anatolia, Eastern Thrace, and some islands. A population exchange between Greece and Turkey was agreed upon, forcing over 1.5 million Christians and almost half a million Muslims to move. This disaster ended the Megali Idea and left Greece exhausted, demoralized, and with a huge number of Greek refugees to house and feed.

Republic and Monarchy (1922–1940)

The disaster deepened Greece's political crisis. The returning army, led by Venizelist officers, forced King Constantine to step down again in September 1922. His son, George II, became king. A "Revolutionary Committee" punished royalists, leading to the "Trial of the Six".

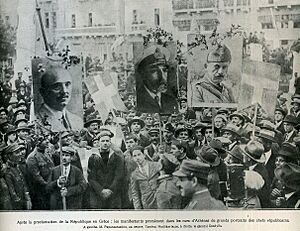

In 1923, an election was held to create a new constitution. King George II was asked to leave the country. On March 25, 1924, the Second Hellenic Republic was declared, confirmed by a public vote a month later.

However, the new Republic was unstable. The National Schism continued, as monarchists didn't accept the Republic. The army, which had a lot of power, often interfered in politics.

Greece was isolated and vulnerable. The economy was in ruins after a decade of war and a sudden increase in population due to refugees. However, the refugees also brought new energy. Many were entrepreneurs and educated, becoming strong supporters of Venizelos and the Republic.

In 1925, General Theodoros Pangalos took power in a coup and ruled as a dictator for a year. He was overthrown by another general, Georgios Kondylis, who restored the Republic.

In 1928, Venizelos returned from exile. His party won the election, and he formed a government that lasted its full four-year term. He made many domestic reforms and improved Greece's international relations, even making peace with Turkey.

The Great Depression hit Greece hard, as it was a poor country relying on farm exports. High unemployment and social unrest followed. The Communist Party of Greece grew quickly. Venizelos had to stop paying Greece's national debt in 1932 and lost power.

Two failed military coups by Venizelos's supporters in 1933 and 1935 tried to save the Republic but had the opposite effect. In October 1935, Georgios Kondylis abolished the Republic and restored the monarchy. A rigged public vote confirmed the change, and King George II returned.

King George II appointed Ioannis Metaxas, a retired general, as interim prime minister. Metaxas believed a strong government was needed to prevent social conflict and stop the Communists. On August 4, 1936, with the King's support, he suspended parliament and established the 4th of August Regime. Communists were suppressed, and liberal leaders were exiled.

Metaxas's regime adopted some ideas from Fascist Italy, like promoting a "Third Hellenic Civilization" and the Roman salute. It also introduced social programs like the Greek Social Insurance Institute (IKA), which is still Greece's biggest social security system.

The regime didn't have widespread popular support, but people were generally apathetic. Metaxas also improved Greece's defenses, building the "Metaxas Line" in preparation for war. Despite his admiration for Fascism and economic ties with Nazi Germany, Metaxas followed a policy of neutrality. Britain guaranteed Greece's borders in 1939. So, when World War II began in September 1939, Greece remained neutral.

Greece in World War II

Despite its neutrality, Greece became a target for Mussolini's Italy. Italian troops crossed the border on October 28, 1940, starting the Greco-Italian War. But the determined Greek defense pushed them back into Albania.

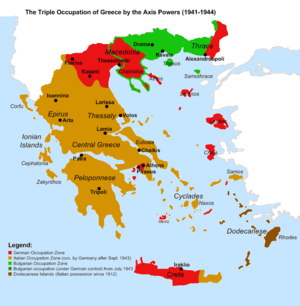

Metaxas died suddenly in January 1941. King George kept the authoritarian government in place. Adolf Hitler was forced to send German troops to help Italy. Germany attacked Greece through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria on April 6, 1941. Despite British help, the Germans quickly took over most of the country by the end of May. The King and government escaped to Crete, then to Egypt, where a Greek government in exile was formed.

Greece was divided into German, Italian, and Bulgarian zones. A puppet government was set up in Athens. Greece suffered terribly during the occupation. The Germans took most of the country's food, leading to the Great Greek Famine. Hundreds of thousands of Greeks died, especially in the winter of 1941–1942.

In the mountains, several Greek resistance movements emerged. By mid-1943, the Axis forces only controlled major towns and roads, while a "Free Greece" was set up in the mountains. In September 1943, after Italy joined the Allies, German forces invaded the Italian occupation zones in Greece.

The largest resistance group, the National Liberation Front (EAM), was controlled by the Communist Party of Greece. Its armed wing, ELAS, soon fought against non-Communist groups. The exiled government in Cairo had little influence in occupied Greece, partly because King George II was unpopular.

As Germany's defeat neared, Greek political groups met in Lebanon in May 1944 and formed a government of national unity.

Greek Civil War (1944–1949)

German forces left Greece on October 12, 1944, and the government in exile returned to Athens. After the Germans left, the EAM-ELAS guerrilla army controlled most of Greece. But their leaders were hesitant to take full control, knowing that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had agreed that Greece would be in the British sphere of influence.

Tensions between the British-backed government and EAM grew, especially over disarming the armed groups. This led to EAM ministers resigning from the government.

On December 3, 1944, a large pro-EAM protest in Athens turned violent. This started an intense street-by-street fight with British and monarchist forces. After three weeks, the Communists were defeated. An agreement ended the conflict and disarmed ELAS. An unstable government was formed. However, a "White Terror" against anti-EAM groups made tensions worse.

The Communists boycotted the March 1946 elections, and fighting broke out again on the same day. By the end of 1946, the Communist Democratic Army of Greece was formed, fighting against the government's National Army. The National Army was supported first by Britain and then by the United States after 1947.

Communist forces had successes in 1947–1948, moving freely across much of mainland Greece. But with major reorganization, forced movement of rural populations, and American support, the National Army slowly regained control. In 1949, the Communists suffered a big blow when Yugoslavia closed its borders after a split with the Soviet Union. Finally, in August 1949, the National Army launched an offensive that forced the remaining rebels to surrender or flee.

The civil war killed 100,000 people and caused huge economic damage. Many Greeks were forced to leave their homes, and many emigrated to other countries like Australia.

The postwar agreements ended Greece's territorial expansion. In 1947, Italy gave the Dodecanese islands to Greece. These were the last majority-Greek-speaking areas to join Greece, except for Cyprus.

Postwar Greece (1950–1973)

After the civil war, Greece wanted to join Western democracies and became a member of NATO in 1952.

In the early 1950s, center parties gained power. These governments were often influenced by the United States. The Left, which had been excluded from politics, found a voice through the EDA party in 1951.

The 1960s were a time of fast economic growth for Greece. A major event was Greece joining the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1962, aiming for a common market.

Greece's economy grew quickly, especially in manufacturing (textiles, chemicals, metals) and construction. A unique Greek system called antiparochi allowed landowners to give their land to developers in exchange for apartments in the new buildings. This helped housing but also led to the demolition of many old, beautiful buildings.

During this decade, youth culture became more prominent. Young people pushed for social rights and education reforms. The independence of Cyprus also became a major focus for young activists.

Military Rule (1967–1974)

Greece fell into a long political crisis. On April 21, 1967, a group of right-wing colonels led by Georgios Papadopoulos seized power in a coup d'état. This started the Regime of the Colonels.

Civil liberties were taken away, military courts were set up, and political parties were banned. Thousands of suspected communists and political opponents were jailed or sent to remote islands. The junta's early years saw economic growth and large infrastructure projects. However, the regime was widely criticized abroad. Inside Greece, unhappiness grew after 1970 when the economy slowed down.

Even the military, the regime's base, was affected. In May 1973, a planned coup by the navy was stopped, but some officers sought political asylum in Italy. In response, Papadopoulos tried to move towards a controlled democracy. He abolished the monarchy and declared himself President.

Transition to Democracy (1973–2009)

On November 25, 1973, after a bloody student uprising in Athens, a hardliner named Dimitrios Ioannides overthrew Papadopoulos. He tried to continue the dictatorship, but the uprising had triggered popular unrest. Ioannides's attempt in July 1974 to overthrow the President of Cyprus brought Greece to the brink of war with Turkey. Turkey then invaded Cyprus and occupied part of the island.

Senior Greek military officers then withdrew their support from the junta, and it collapsed. Constantine Karamanlis returned from exile in France to form a government of national unity until elections could be held. Karamanlis worked to prevent war with Turkey and also made the Communist Party legal again. His new party, New Democracy, won the November 1974 elections, and he became prime minister.

After a public vote in 1974 abolished the monarchy, a new constitution was approved in 1975. Parliament elected Constantine Tsatsos as President. In 1980, Prime Minister Karamanlis was elected president.

On January 1, 1981, Greece became the tenth member of the European Community (now the European Union). In 1981, Greece elected its first socialist government when the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), led by Andreas Papandreou, won the elections.

Greece had two parliamentary elections in 1989, both resulting in weak coalition governments. In 1990, New Democracy, led by Constantine Mitsotakis, won. However, a split within his party led to the government's collapse. In new elections in 1993, Papandreou returned to power.

In 1996, Papandreou resigned due to illness, and Costas Simitis became prime minister. Simitis won re-election in 1996 and 2000. In 2004, Simitis retired, and George Papandreou became PASOK leader.

In the March 2004 elections, PASOK was defeated by New Democracy, led by Kostas Karamanlis, the nephew of the former president. New Democracy also won the 2007 elections. In the 2009 elections, PASOK became the majority party, and George Papandreou became Prime Minister. Later, New Democracy and PASOK formed a grand coalition government.

Greece's Economic Challenges (2009–Present)

Government-Debt Crisis (2009–2018)

From late 2009, people worried that Greece might not be able to pay its debts because government debt levels had increased a lot. This led to a crisis of confidence. Greece's debt was downgraded to "junk bonds," causing alarm in financial markets.

On May 2, 2010, Eurozone countries and the International Monetary Fund agreed to a €110 billion loan for Greece. This loan came with strict conditions: Greece had to implement harsh austerity measures, which meant cutting government spending and raising taxes. These measures were very unpopular and led to many protests and unrest.

There were fears that if Greece couldn't pay its debts, it would affect many other countries in the European Union and threaten the stability of the euro currency. Some even thought Greece might have to leave the euro and go back to its old currency, the drachma. In 2014, Greece returned to the global bond market, showing some recovery.

Coalition Government and SYRIZA (2012–2019)

After the May 2012 elections, no party could form a government. New elections were called for June 2012. New Democracy won more seats this time. On June 20, 2012, Antonis Samaras, the leader of New Democracy, formed a coalition government with PASOK and DIMAR.

Due to the unpopular austerity measures, Greeks voted the anti-austerity, left-wing SYRIZA party into power in January 2015. Samaras accepted defeat.

SYRIZA lost its majority in August 2015 when some MPs withdrew support. SYRIZA won the September 2015 elections again but didn't get an outright majority. They formed a coalition with the Independent Greeks, a right-wing party.

SYRIZA suffered big defeats in the 2019 European Parliament election. Prime Minister and SYRIZA leader, Alexis Tsipras, resigned and called for a snap election. This resulted in a majority for New Democracy.

New Democracy Returns to Power (2019–Present)

On July 7, 2019, Kyriakos Mitsotakis was sworn in as the new Prime Minister of Greece. He formed a center-right government after his New Democracy party won the 2019 election by a large margin.

In March 2020, Greece's parliament elected Katerina Sakellaropoulou as the first female President of Greece.

In June 2023, the conservative New Democracy party won the legislative election again. This meant another four-year term as prime minister for Kyriakos Mitsotakis.

Images for kids

-

The symbolic start of the Occupation: German soldiers raising the German War Flag over the Acropolis. It would be taken down in one of the first acts of the Greek Resistance.

-

Workmen grade the street in front of new housing constructed with the help of Marshall Plan funds in Greece.

See also

- Timeline of Greek history

- Timeline of modern Greek history