Greek genocide facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Greek genocide |

|

|---|---|

| Part of World War I, the aftermath of World War I and the late Ottoman genocides | |

| Location | Ottoman Empire |

| Date | 1913–1923 |

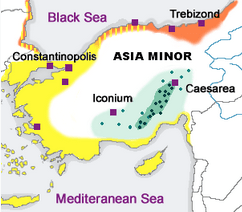

| Target | Greek population, particularly from Pontus, Cappadocia, Ionia and Eastern Thrace |

|

Attack type

|

Deportation, genocide, ethnic cleansing, death marches |

| Deaths | 300,000–900,000 (see casualties section below) |

| Perpetrators | Ottoman Empire, Turkish National Movement |

| Trials | Ottoman Special Military Tribunal |

| Motive | Anti-Greek sentiment, Turkification, Anti-Eastern Orthodox sentiment |

The Greek genocide (Greek: Γενοκτονία των Ελλήνων, romanized: Genoktonía ton Ellínon) was a terrible time when many Greek people living in the Ottoman Empire were killed or forced to leave their homes. This happened mostly during and after World War I, from 1914 to 1922. It also continued during the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1923).

The killings were carried out because of people's religion and where they came from. The Ottoman government, first led by the Three Pashas and later by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, was responsible. Many Greeks were killed in massacres, forced to march long distances into deserts, or simply kicked out of their homes. Important Eastern Orthodox churches and historical sites were also destroyed. Hundreds of thousands of Ottoman Greeks died during this period.

Most of the people who survived fled to Greece. This added a lot to Greece's population. Some Greeks, especially those in the eastern parts of the empire, found safety in the nearby Russian Empire. By late 1922, most Greeks in Asia Minor had either fled or been killed. Those who remained were later moved to Greece in 1923 as part of a population exchange between Greece and Turkey. This agreement made it official that refugees could not return.

Other groups, like the Assyrians and Armenians, were also attacked by the Ottoman Empire around the same time. Many experts and groups agree that these events were all part of the same plan to remove Christian minorities. Countries like Greece, Cyprus, and the United States have officially recognized these events as genocide.

Contents

Why it Happened: The Background

When World War I started, Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) was home to many different groups of people. There were Turks, Azeris, and older groups like Greeks, Armenians, Kurds, and Assyrians.

One reason for the attacks on Greek Christians was fear. Some Turkish leaders worried that these Greeks would support the Ottoman Empire's enemies. They also believed that to create a modern Turkish country, they needed to remove all minorities who might threaten a purely Turkish nation.

In 1915, a German military officer reported that the Ottoman Minister of War, Enver Pasha, wanted to "solve the Greek problem" just like he had "solved the Armenian problem." This was a clear reference to the Armenian genocide. Germany and the Ottoman Empire were allies during World War I. In 1917, the German Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, said that the Turks planned to remove the Greek people. He noted that the Turks were forcing Greeks to move to inland areas without enough food or care. Their homes were then looted and burned. He said, "Whatever was done to the Armenians is being repeated with the Greeks."

Greeks in Asia Minor: A Long History

Greeks have lived in Asia Minor for a very long time, since at least 1450 BC. The famous Greek poet Homer lived there around 800 BC. Many ancient Greek thinkers, like the mathematician Thales and the philosopher Heraclitus, were from Anatolia. Greeks called the Black Sea the "Euxinos Pontos," meaning "hospitable sea." From the 8th century BC, they started settling along its coasts. Important Greek cities there included Trebizond and Sinope.

After Alexander the Great's conquests, Greek culture and language became very strong in Asia Minor. By the early centuries AD, the local languages were replaced by Koine Greek. From then until the late Middle Ages, most people in Asia Minor were Greek Orthodox Christians and spoke Greek.

Greek culture thrived for a thousand years under the Eastern Roman Empire, which was mainly Greek-speaking. Many famous Greeks, like Saint Nicholas and the architect of Hagia Sophia, came from Asia Minor.

When the Turkic people started taking over Asia Minor in the late Middle Ages, Byzantine Greeks were the largest group living there. Even after the Turks conquered the inner lands, the Black Sea coast remained a Greek Christian state, the Empire of Trebizond. It was finally conquered by the Ottomans in 1461. Over the next four centuries, the Greek people in Asia Minor slowly became a minority as Turkish culture became dominant.

Events Leading to the Genocide

Before World War I (1913-1914)

Starting in 1913, the Ottomans began a plan to expel and forcibly move Greeks. This focused on Greeks in the Aegean region and eastern Thrace. The government used a "dual-track" method. This meant official actions were combined with secret, violent acts by groups supported by the state. This allowed the government to pretend they were not responsible.

Local military and government officials were sometimes involved in planning attacks and looting against Greeks. The Greek ambassador and the Ecumenical Patriarchate (the head of the Greek Orthodox Church) complained to the Ottoman government. In protest, the Patriarchate closed Greek churches and schools in June 1914.

Talat Pasha, a key Ottoman leader, visited the areas to investigate. He claimed he knew nothing about the events. However, he secretly advised the head of the "cleansing" operation to be careful not to be "visible." There were also organized boycotts of Greek businesses, started by the Ottoman Interior Ministry. The British ambassador said these boycotts were directly caused by the Committee of Union and Progress, a powerful political group. He noted that anyone, Greek or Muslim, who entered a non-Muslim shop was beaten.

One of the worst attacks happened in Phocaea on June 12, 1914. This town in western Anatolia was destroyed by Turkish irregular troops. Many civilians were killed, and the people fled to Greece. A French witness said these attacks were organized to remove Christian villagers. In another attack, villagers in Serenkieuy tried to fight back but were outnumbered.

In the summer of 1914, the Special Organization forced Greek men of military age into Labour Battalions. Hundreds of thousands died in these groups. They were sent hundreds of miles inland to do hard labor like building roads. Many died from harsh conditions, mistreatment, and outright killings by their guards.

The forced removal of Christians, especially Greeks, from western Anatolia was very similar to the policy against the Armenians. US ambassador Henry Morgenthau, Sr. and historian Arnold J. Toynbee noted this. Both involved the Special Organization and labour battalions. Both used a plan of unofficial violence combined with official population policies. This policy of persecution spread to other Greek communities, including those in Pontus and Cappadocia.

During World War I (1914-1918)

In November 1914, Turkish troops destroyed Christian properties and killed several Christians in Trabzon. After this, the Ottoman policy changed slightly. The government focused on moving Greeks from coastal areas, especially the Black Sea region, to inland Anatolia. This was because Germany demanded that the persecution of Greeks stop. Greece's leader, Eleftherios Venizelos, had made this a condition for Greece to remain neutral in the war. He also threatened to do the same to Muslims living in Greece if the Ottoman policy did not change.

Even with this change, attacks and murders continued in the provinces. Local officials often did not punish these crimes. Violence and demands for money increased, which made many Greeks want their country to join the Allies.

In July 1915, the Greek representative said that the deportations were "an annihilation war against the Greek nation in Turkey." He believed the goal was to convert Greeks to Islam so that fewer Christians would be left if European countries tried to protect them after the war. By 1918, a British official named George W. Rendel reported that "over 500,000 Greeks were deported of whom comparatively few survived." The US ambassador to the Ottoman Empire said that between 200,000 and 1,000,000 Greeks were forced to move inland, mostly on foot.

The forced movement of Greek settlements continued, though on a smaller scale. It targeted areas that were important for military reasons. An account from 1919 said that many villages were looted and people were murdered during these evacuations. Many died because they were not given time to prepare or were sent to places where they could not live.

Ottoman policy towards Greeks changed again in late 1916. With Allied forces occupying Greek islands and Russia advancing in Anatolia, the Ottomans prepared to deport Greeks from border areas. In January 1917, Talat Pasha ordered the deportation of Greeks from the Samsun district. He said there should be "no assaults on any persons or property." However, this was not followed. Men were taken to labour battalions, women and children were attacked, and villages were looted by Muslim neighbors.

In March 1917, the people of Ayvalık, a town of about 30,000, were forcibly deported inland. This operation included death marches, looting, and massacres. The bishop of Samsun reported that 30,000 people were deported to the Ankara region, and many were killed.

A Swedish ambassador reported in 1917 that the deportations were not just for men but also for women and children. He believed this was done to make it easier to take their property. An Ottoman official named Rafet Bey was involved in the genocide of Greeks. In November 1916, he reportedly said, "We must finish off the Greeks as we did with the Armenians."

Greeks in the Pontus region fought back by forming armed groups. They used weapons from World War I battlefields or supplied by the Russian army. By 1920, these groups had about 18,000 men. A Greek division was formed from ethnic Greeks in the Russian army and local recruits. This division fought against the Ottoman army and other groups, helping Greek refugees escape to Russian-held areas.

Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922)

After the Ottoman Empire surrendered in 1918, it was controlled by the winning Allied Powers. However, they did not punish those responsible for the genocide. Killings and deportations continued under the new Turkish national movement led by Mustafa Kemal.

The planned killing and deportation of Greeks in Asia Minor, which started in 1914, led to more terrible events during the Greco-Turkish War. This war began when Greece landed troops in Smyrna in May 1919 and ended when the Turks recaptured Smyrna in September 1922. The Great Fire of Smyrna followed. Some estimates say 10,000 to 100,000 Greeks and Armenians died in the fire and related massacres. About 150,000 to 200,000 Greeks were forced out after the fire. Around 30,000 Greek and Armenian men were sent to inland Asia Minor, where most were killed or died from harsh conditions.

British historian Arnold J. Toynbee noted that the Greek landing in Smyrna actually helped create the Turkish National Movement. He suggested that the Greeks of Pontus and the Turks in Greek-occupied areas were victims of miscalculations by Greek and British leaders.

Help for Victims

In 1917, a group called the Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor was formed. It worked with the Near East Relief to help Ottoman Greeks. They provided aid to Greeks in Thrace and Asia Minor. The group stopped its work in 1921, but other organizations continued to help.

How Many People Died?

Experts like Benny Morris and Dror Ze'evi say that "several hundred thousand Ottoman Greeks had died" because of Ottoman and Turkish government policies.

For the entire period between 1914 and 1922, estimates of the death toll range from 289,000 to 750,000 people. The Greek government and the Patriarchate claimed that a total of one million people were killed.

What Happened Next?

After World War I, the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres called the wartime Turkish government "terrorist." It included plans to fix the wrongs done to people during the massacres. However, the Turkish government never approved this treaty. It was later replaced by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. This new treaty included an "Amnesty Declaration," meaning no one was punished for war crimes.

In 1923, a population exchange between Greece and Turkey took place. This meant that almost all Greeks in Turkey were moved to Greece, and most Turks in Greece were moved to Turkey. It is hard to know exactly how many Greeks died between 1914 and 1923, or how many were forced to move to Greece or fled to the Soviet Union.

Later, in 1955, the Istanbul Pogrom caused most of the remaining Greeks in Istanbul to flee the country. Some historians say this event was a crime against humanity. They believe the forced flight of Greeks fits the definition of genocide.

Remembering the Greek Genocide

Many memorials have been built to remember the suffering of Ottoman Greeks. These memorials can be found in Greece and other countries like Australia, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and the United States.

See also

- Armenian genocide

- Sayfo

- Burning of Smyrna

- Deportations of Kurds (1916–1934)

- Greek refugees

- Republic of Pontus

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |