Umberto Nobile facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Umberto Nobile

|

|

|---|---|

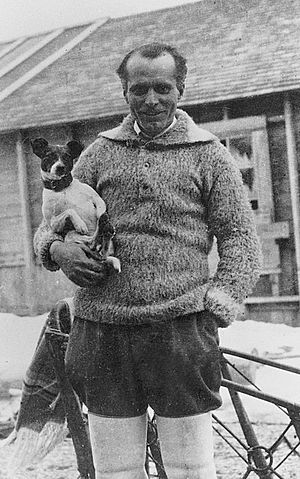

Umberto Nobile c. 1923

|

|

| Member of the Italian Constituent Assembly | |

| In office 25 June 1946 – 31 January 1948 |

|

| Parliamentary group | Communist |

| Constituency | Lazio |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 January 1885 Lauro, Italy |

| Died | 30 July 1978 (aged 93) Rome, Italy |

| Resting place | Cimitero Flaminio, Rome |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | Maria |

| Alma mater | University of Naples Federico II |

| Occupation | Aviator, university professor |

| Known for | Polar expeditions of Norge and Italia |

| Committees | Committee for the Constitution |

| Awards |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Italy |

| Branch/service | Royal Italian Air Force |

| Years of service | 1911-1929 |

| Rank | Generale di divisione area |

Umberto Nobile (born January 21, 1885 – died July 30, 1978) was an Italian aviator, engineer, and explorer. He was famous for his work with airships and his daring trips to the Arctic.

Nobile was a key person in developing and promoting semi-rigid airships between the two World Wars. He is best known for designing and flying the airship Norge. This airship might have been the first aircraft to reach the North Pole. It was definitely the first to fly across the polar ice cap from Europe to America. Nobile also designed and flew a second polar airship, the Italia. This second trip ended in a difficult crash, leading to a huge international rescue effort.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Umberto Nobile was born in Lauro, Italy. His family were small landowners. After finishing his engineering degree at the University of Naples Federico II in 1908, Nobile started working for the Italian state railways.

In 1911, he became interested in aeronautical engineering. He joined a course offered by the Italian Army. During World War I, he worked as a military engineer. He designed airships used for finding submarines. He also taught courses for future officers. In 1918, he designed Italy's first parachute. From 1919 to 1927, he was the director of the Military Factory for Aeronautical Construction and Experience in Rome.

Nobile also taught at the University of Naples. He earned his test pilot's license and wrote a textbook called Elements of Aerodynamics.

He believed that medium-sized, semi-rigid airships were better than other designs. He focused on creating them. One of his early projects was the T-34, an airship made for a trip across the Atlantic Ocean. The United States Army bought this airship in 1921 and named it the Roma. In February 1922, the hydrogen-fueled Roma crashed in Norfolk, Virginia, after hitting power lines. This was a major aviation disaster at the time.

In the same year, Nobile worked with Gianni Caproni on the first Italian all-metal aircraft, the Caproni Ca.73. He also traveled to the United States to work as a consultant for Goodyear. In 1923, he began designing a new airship, the N-1. This airship was built for countries like the United States, Spain, Argentina, and Japan. He even went to Japan in 1927 to help assemble the N-3 airship for the Imperial Japanese Navy. He took part in several test flights there.

Arctic Expeditions

Nobile is most famous for his adventures in the Arctic.

The Norge Expedition

In late 1925, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen asked Nobile to help with a flight to the North Pole. At that time, no one had flown over the North Pole yet. Amundsen had tried before in 1925 but had to land his planes on the ice.

The Italian State Airship Factory provided Nobile's N-1 airship for the expedition. Amundsen insisted that Nobile be the pilot and that five of the crew members be Italian. Amundsen named the airship Norge (meaning Norway). On April 14, 1926, the airship left Italy. It stopped in England and Norway on its way to Ny-Ålesund in Svalbard, which was its starting point for the Arctic flight.

On May 11, 1926, the Norge expedition left Svalbard. About 15 and a half hours later, the airship flew over the North Pole. It landed two days later in Teller, Alaska. Strong winds made it impossible to land at the planned spot in Nome, Alaska. Later, it was confirmed that the Norge crew was likely the first to fly over the North Pole. Another American flight that claimed to be first was later found to have had problems with its navigation records.

The Norge flight from "Rome to Nome" was seen as a huge achievement in aviation. However, disagreements soon started between Nobile (the designer and pilot) and Amundsen (the expedition leader). They argued about who deserved more credit for the success. The Italian government also praised Nobile's work, which made the disagreement worse.

The Italia Expedition

Despite the arguments, Nobile kept good relationships with other polar scientists. He began planning a new expedition, this time completely under Italian control. The new airship, the Italia, was very similar to the Norge. It was prepared for polar flight between 1927 and 1928. The city of Milan helped pay for the expedition. The Italian government provided the airship and a support ship called Città di Milano.

On May 23, 1928, after a long flight to the Siberian Arctic islands, the Italia began its flight to the North Pole. Nobile was both the pilot and the expedition leader. On May 24, the ship reached the Pole. It was on its way back to Svalbard when it flew into a storm. On May 25, the Italia crashed onto the ice. Ten of the 16 crew members were thrown onto the ice. The other six were trapped in the airship's upper part as it floated away. Their fate was never known. One of the ten men on the ice died from the crash. Nobile and others were injured.

The crew on the ice managed to save some important items from the crashed airship. These included a radio, a tent (which they painted red to be seen easily), and boxes of food and survival gear. An engineer named Ettore Arduino quickly threw these items onto the ice before he and his companions were carried away by the floating airship. As days passed, the ice they were on drifted.

A few days after the crash, the meteorologist Finn Malmgren and Nobile's two Italian companions decided to try walking towards land. Malmgren, who was injured and weak, asked the two Italians to go on without him. These two were later picked up by a Soviet icebreaker.

A movie called The Red Tent (1969) was made about these events. It was a joint Italian and Soviet film.

The Rescue Mission

After the crash, many countries, including the Soviet Union, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Italy, started a huge air and sea rescue effort. Even Roald Amundsen, who had argued with Nobile before, joined the rescue. He flew in a French seaplane towards the rescue headquarters. Sadly, his plane disappeared, and he and his crew were never found.

After a month on the ice, the first rescue plane, a Swedish ski plane, landed near the crash site. The pilot, Lieutenant Einar Lundborg, would only take Nobile. He said his plane could only carry one survivor, and the other injured men were too heavy. Nobile was flown to a base camp. When Lundborg returned alone to pick up another survivor, his plane crashed, and he became trapped with the others.

Nobile eventually reached the support ship Città di Milano. He felt that the rescue efforts were not well organized. His attempts to help were blocked, and his messages to the survivors were censored. Italian newspapers wrongly reported that his rescue was a sign of cowardice. After 48 days on the ice, the last five men of his crew were rescued by the Soviet icebreaker Krasin. Nobile wanted to keep searching for the six crew members who had floated away with the airship, but he was ordered back to Rome.

When Nobile and his crew arrived in Rome on July 31, two hundred thousand cheering Italians met them. This popularity surprised those who had been criticizing Nobile. An official investigation blamed Nobile for the disaster. He was accused of abandoning his men. He spent the rest of his life trying to clear his name. Because of the findings, General Nobile resigned from the air force in March 1929.

Later Life

In July 1931, Nobile joined a Soviet icebreaker expedition to the Arctic. In January 1932, he moved to the Soviet Union and lived there for almost five years. He worked on the Soviet airship program. He oversaw the building of three airships and designed two more for military use.

He returned to Italy in December 1936. He was appointed a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. For a few months, he also worked on aviation projects with Caproni.

Because of difficulties with the Italian government, he moved to the United States in 1939. He taught at Lewis University in Illinois. He was allowed to stay even after Italy declared war on the United States, but he chose to return to Europe in May 1942. After a short time in Rome, he moved to Spain. He stayed there until the Italian leader was removed from power. Then he returned to Italy for good.

In 1945, the Italian air force cleared Nobile of all charges related to the Italia crash. They gave him back his rank as major general and promoted him to lieutenant general. He also received back pay from 1928. The next year, he was elected to the Italian Constituent Assembly. He was part of the committee that wrote the main draft of the Italian Constitution.

In 1948, Nobile returned to teaching at the University of Naples. He studied and taught about aviation and space travel. He continued to give interviews and write books until he died. He passed away in Rome on July 30, 1978, at the age of 93. This was shortly after celebrations for the fiftieth anniversary of his two Arctic expeditions. The Italian Air Force Museum has a large exhibition about his achievements. There is also a museum in his hometown of Lauro that collects his documents and items.

|

See also

In Spanish: Umberto Nobile para niños

In Spanish: Umberto Nobile para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |