Discovery Expedition facts for kids

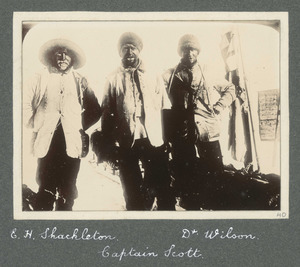

The Discovery Expedition (1901–1904) was the first official British journey to explore Antarctica. It was a big adventure, happening sixty years after James Clark Ross's voyage. This expedition aimed to do important scientific research and explore new parts of the largely unknown continent. Many famous Antarctic explorers started their careers here, including Robert Falcon Scott (who led the trip), Ernest Shackleton, Edward Wilson, Frank Wild, and Tom Crean.

The expedition made many scientific discoveries in biology, zoology, geology, meteorology, and magnetism. They found the only snow-free valleys in Antarctica, which have the continent's longest river. They also discovered a colony of emperor penguins at Cape Crozier, King Edward VII Land, and the Polar Plateau. This plateau is where the South Pole is located. The team tried to reach the South Pole, getting as far south as 82°17′S. The Discovery Expedition was a major step for British Antarctic exploration.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Adventure

Earlier Explorers

Between 1839 and 1843, James Clark Ross, a Royal Navy Captain, sailed to Antarctica. He commanded two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. Ross explored a new part of Antarctica that later British expeditions would also visit.

Ross mapped this area and named many places. These included the Ross Sea, the Great Ice Barrier (now called the Ross Ice Shelf), Ross Island, McMurdo Sound, and the volcanoes Mount Erebus and Mount Terror. He tried to sail through the Ice Barrier but couldn't. His furthest south point was 78°10′ in 1842.

For 50 years after Ross, no one explored this part of Antarctica. Then, in 1895, a Norwegian whaling ship briefly landed at Cape Adare. Four years later, Carsten Borchgrevink, who was on that whaling trip, led his own expedition. He landed at Cape Adare in 1899 and spent the winter there. The next summer, his team sledged south on the Ice Barrier, reaching 78°50′S.

The Discovery Expedition was planned when many countries were interested in Antarctica. Other expeditions were also setting off around the same time. These included German, Swedish, French, and British teams exploring different parts of the continent.

How Scott Was Chosen

After the Napoleonic War, the Royal Navy often led polar explorations. But after a difficult North Pole expedition in 1874–76, the Navy decided polar trips were too risky and costly.

However, Sir Clements Markham, a former naval officer, strongly believed the Navy should return to polar exploration. He was secretary, and later president, of the Royal Geographical Society. In 1893, a famous biologist, Sir John Murray, called for a new, large-scale British expedition to Antarctica. Markham and the Royal Society strongly supported this idea.

Markham had a habit of noticing promising young naval officers. He first saw Midshipman Robert Falcon Scott in 1887. Thirteen years later, Scott was looking for a way to advance his career. A meeting with Sir Clements led Scott to apply to lead the expedition. Markham strongly backed Scott, and he was appointed leader on May 25, 1900. He was quickly promoted to commander.

There was a disagreement about who should be in charge. Markham wanted a naval officer like Scott to have full command. Scientists on the committee wanted a scientist to lead the land exploration. Scott insisted he must have complete control of both the ship and the land parties. Scott and Markham won this argument. The chief scientist, John Walter Gregory, resigned. He felt the scientific work should not be "secondary to naval adventure."

The Team

Markham hoped for a full Royal Navy expedition. But the Navy could only spare a few officers, including Scott, Charles Royds, Michael Barne, and Reginald Skelton. The other officers were from the Merchant Marine. This included Albert Armitage, the second-in-command, and Ernest Shackleton. Shackleton was in charge of supplies and entertainment.

About twenty naval sailors also joined. The rest of the crew were from the merchant service or other jobs. Some of these men became famous Antarctic explorers later. They included Frank Wild, William Lashly, Thomas Crean, Edgar Evans, and Ernest Joyce. Even though it wasn't a formal Navy project, Scott ran the expedition like a naval ship.

The scientific team was quite new to this kind of work. The geologist, Hartley Ferrar, was only 22. The marine biologist, Thomas Vere Hodgson, was more experienced. The senior doctor, Reginald Koettlitz, was 39 and had been on an Arctic expedition before. The junior doctor and zoologist was Edward Adrian Wilson. He became a close friend of Scott's.

Planning the Trip

Money and Ship

The expedition cost about £90,000 (a lot of money back then!). The British Government offered half the money if the two societies (Royal Society and Royal Geographical Society) could raise the other half. They did, thanks to a large donation from Llewellyn W. Longstaff. Other groups and people also contributed.

Many companies also helped by giving supplies. Colman's gave mustard and flour, Cadbury's gave chocolate, and Bird's gave baking powders. Jaeger gave a big discount on special clothes.

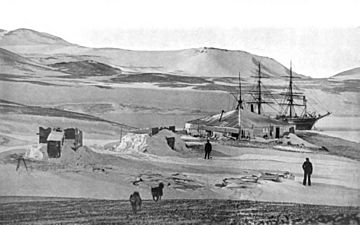

The expedition's ship was built in Dundee, Scotland. It was a special research vessel designed for Antarctic waters. It was one of the last three-masted wooden sailing ships built in Britain. The ship was named S.Y. Discovery and launched in March 1901.

Dogs and Goals

Scott asked Fridtjof Nansen, a famous Norwegian explorer, for advice on equipment. Following Nansen's advice, the team ordered 25 Siberian sledge-dogs.

The Discovery Expedition was to work in the Ross Sea area of Antarctica. This was the same area Ross and Borchgrevink had explored. The main goals were to map the unknown parts of the south polar lands and to do a magnetic survey. They also wanted to study the weather, oceans, geology, and biology. The instructions said that neither of these goals should be more important than the other.

The geographical goals included exploring the Ice Barrier to its end. They also wanted to find land that Ross thought might be east of the Barrier. If they had to spend the winter there, they were to explore the western mountains, go south, and explore the volcanic area.

The Expedition Begins

First Year's Journey

The Discovery left England on August 6, 1901. It arrived in New Zealand on November 29. The expedition's dogs were kept on Quail Island for a while. After three weeks of final preparations, the ship was ready. On December 21, as the ship left Lyttelton, a young sailor named Charles Bonner fell from the mainmast and died. He was buried two days later.

Discovery sailed south, reaching Cape Adare on January 9, 1902. After a quick stop, the ship continued along the Victoria Land coast. At McMurdo Sound, Discovery turned east. They landed at Cape Crozier and set up a message point for future relief ships. On January 30, they confirmed the land Ross had predicted, naming it King Edward VII Land.

On February 4, Scott landed on the Ice Barrier. He used an observation balloon to look around. Scott went up over 600 feet (180 m). Shackleton also took a flight. All they could see was endless ice. Wilson thought the flights were "perfect madness."

Winter Camp

Discovery then sailed west to find a permanent winter home. On February 8, they entered McMurdo Sound and anchored in Winter Quarters Bay. Wilson felt lucky to find such a safe place for the ship. Work began ashore to build huts on a rocky area called Hut Point. Scott decided the team would live on the ship, letting it freeze into the sea ice. The main hut was used for storage.

No one on the team was a skilled skier, and few had experience with dog sledges. The early attempts to learn were not good. This made Scott prefer man-hauling (pulling sledges themselves). The dangers of the new environment became clear on March 11. A group returning from Cape Crozier got stuck in a blizzard. One sailor, George Vince, fell off a cliff and died. A cross in his memory still stands at Hut Point.

During the winter months (May–August), the scientists worked in their labs. Equipment and supplies were prepared for the next season. For fun, there were plays and lectures. Shackleton edited a newspaper called the South Polar Times. Outside, they played football on the ice. They also kept up with weather observations. As winter ended, they practiced sledge runs. This was to test gear for the big southern journey Scott, Wilson, and Shackleton planned.

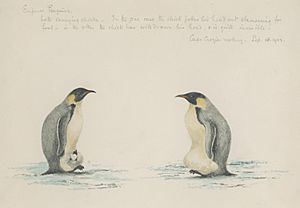

Meanwhile, a team led by Royds went to Cape Crozier. They found a colony of emperor penguins. Another group, led by Armitage, explored the western mountains. They returned in October with the first signs of scurvy. Armitage blamed it on Scott not wanting to kill animals for fresh meat. The expedition's diet was quickly changed, and the problem was controlled.

Journey to the South

Scott, Wilson, and Shackleton left on November 2, 1902, with dogs and support teams. Their goal was to go "as far south... as we can, reach the Pole if possible, or find some new land." On November 11, they passed Borchgrevink's furthest south record of 78°50′. But they were not good with dogs, so progress was slow.

After the support teams left, Scott's group started relaying their loads. This meant they traveled three miles for every mile they gained southward. They had problems with dog food, and as the dogs weakened, Wilson had to kill some for the others to eat. The men also struggled with snow blindness, frostbite, and early scurvy symptoms. But they kept going south.

On December 30, 1902, they reached their furthest south point at 82°17′S. The journey back was harder. The remaining dogs died, and Shackleton became very ill with scurvy. Wilson wrote that they all had "slight, though definite symptoms of scurvy." Scott and Wilson struggled on, with Shackleton walking beside them or sometimes being carried on the sledge. They finally reached the ship on February 3, 1903. They had traveled about 960 miles in 93 days.

Help Arrives

While the southern team was away, the relief ship Morning arrived with fresh supplies. The expedition leaders thought Discovery would be free from the ice in early 1903. This would let Scott do more sea exploration. But Discovery was stuck fast in the ice.

Markham had expected this. Morning's captain, William Colbeck, had a secret letter allowing Discovery to stay another year. Since the ship was stuck, some people could go home on Morning. Scott sent the sick Shackleton home, saying he "ought not to risk further hardships." Some stories say Scott and Shackleton had a big argument, but other evidence shows they stayed on good terms for a while.

The Second Year

After the winter of 1903, Scott prepared for the expedition's second main journey. This was to climb the western mountains and explore Victoria Land. An earlier team had reached 8,900 feet (2,700 m). Scott wanted to go west from there, possibly to the South Magnetic Pole. On October 26, 1903, Scott, Lashly, and Edgar Evans set out.

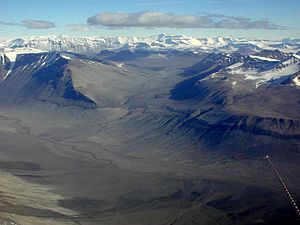

They climbed the Ferrar Glacier, named after the expedition's geologist. They reached 7,000 feet (2,100 m) but were stuck in a blizzard for a week. They finally reached the glacier summit on November 13. They then marched beyond where the earlier team had gone. They discovered the Polar Plateau and were the first to travel on it.

After other teams returned, Scott, Evans, and Lashly continued west across the flat plain for eight more days. They covered about 150 miles. They had lost their navigation tables in a storm, so they didn't know exactly where they were. The journey back was very slow, with supplies running low. On the way down the glacier, Scott and Evans fell into a crevasse but survived. They also discovered a snow-free area, a rare Antarctic "dry valley." Lashly called it "a splendid place for growing spuds." The team reached Discovery on December 24. They had traveled 700 miles in 59 days. This man-hauling journey was much faster than their dog-sledging trip, which made Scott dislike dogs even more.

Other journeys happened while Scott was away. Royds and Bernacchi traveled on the Ice Barrier, taking magnetic readings. Another team explored the Koettlitz Glacier. Wilson went to Cape Crozier to study the emperor penguin colony up close.

Second Rescue Mission

Scott hoped Discovery would be free when he returned, but it was still stuck. They tried to cut the ice with saws, but after 12 days, the ship was still 20 miles (32 km) from open water. On January 5, 1904, the relief ship Morning returned, this time with a second ship, the Terra Nova.

The Admiralty (the British Navy's leaders) had given strict orders. If Discovery couldn't be freed by a certain date, it had to be abandoned. The crew would come home on the two relief ships. This was because the expedition had run out of money. The deadline was February 25. It became a race against time. Explosives were used to break the ice, and the sawing continued.

By the end of January, Discovery was still stuck, two miles (3 km) from the rescuers. On February 10, Scott accepted he might have to leave the ship. But on February 14, most of the ice suddenly broke up! Morning and Terra Nova could finally sail next to Discovery. A final explosive charge cleared the last ice on February 16. The next day, after a brief scare when it got stuck on a sandbar, Discovery began its journey back to New Zealand.

Coming Home and Discoveries

When the expedition returned to Britain, the welcome was quiet at first. Some reporters were surprised the men looked so healthy, as they had heard about scurvy problems. Markham met the ship in Portsmouth on September 10, 1904. But no important people greeted them in London a few days later.

However, the public was very excited. Official recognition soon followed. Scott was quickly promoted to captain. He met King Edward VII and received many medals from Britain and other countries. Other officers and crew also received Polar Medals and promotions.

The main geographical discoveries were:

- King Edward VII Land.

- The Polar Plateau (discovered by climbing the western mountains).

- The first sledge journey on the plateau.

- The journey on the Ice Barrier to a furthest south of 82°17′S.

- They confirmed Ross Island was an island.

- They mapped the Transantarctic Mountains and calculated the heights of over 200 mountains.

- They identified and named many other features.

There were also important scientific discoveries:

- The snow-free Dry Valleys in the western mountains.

- The emperor penguin colony at Cape Crozier.

- Proof that the Ice Barrier was a floating ice shelf.

- A leaf fossil that showed Antarctica was once connected to the super-continent Gondwana.

- Thousands of geological and biological samples were collected, and new sea creatures found.

- The location of the South Magnetic Pole was calculated.

- Wilson found that fresh seal meat helped prevent scurvy. This was important for future expeditions.

The expedition successfully fought scurvy by eating fresh seal meat. Scott recommended this for future polar trips. At the time, doctors knew fresh meat could cure scurvy, but they didn't know it was caused by a lack of vitamin C. So, fresh seal meat was taken on the southern journey "in case we find ourselves attacked by scurvy." Scurvy remained a danger until its causes were fully understood many years later.

What Happened Next

Scott took time off from the Navy to write a book about the expedition, The Voyage of the Discovery. It was published in 1905 and sold well. However, Scott's description of Shackleton's illness during the southern journey caused a disagreement between them.

Scott later returned to his naval career. He became a national hero. The expedition was seen as a great success. Scott's praise for man-hauling (pulling sledges themselves) made people distrust other methods like skis and dogs. This idea was carried into later expeditions.

The Discovery Expedition started the Antarctic careers of many explorers. Besides Scott and Shackleton, Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce returned to Antarctica many times. William Lashly and Edgar Evans became Scott's regular sledging partners. Tom Crean joined both Scott and Shackleton on later trips. Lieutenant "Teddy" Evans, an officer on the relief ship Morning, later joined Scott's next expedition.

Soon after returning to the Navy, Scott planned to go back to Antarctica. But Ernest Shackleton announced his own plans in 1907. He wanted to reach the geographic and magnetic South Poles. Shackleton agreed not to work from McMurdo Sound, which Scott considered his area. But Shackleton couldn't find a safe landing elsewhere and had to break this promise. His expedition was very successful. His southern team got within 100 miles of the South Pole, and his northern team reached the South Magnetic Pole. But Shackleton breaking his promise caused a big rift between the two men.

Scott's plans for a new expedition slowly came together. It would be a large scientific and geographical trip, with the main goal of reaching the South Pole. Scott wanted to avoid any problems with the scientific work this time. He chose Edward Wilson as his chief scientist. The expedition set off in June 1910 on the Terra Nova, one of Discovery's relief ships. Their plans became more complex when Roald Amundsen's Norwegian expedition also arrived in Antarctica. Amundsen's team reached the South Pole on December 14, 1911, and returned safely. Scott and four companions, including Wilson, reached the Pole on January 17, 1912. All five died on the journey back.

See also

- Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

- List of Antarctic expeditions

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |