RRS Discovery facts for kids

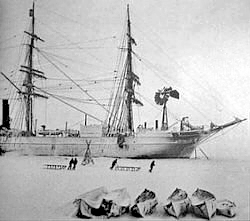

RRS Discovery in Antarctica c. 1923

|

|

| History | |

|---|---|

| Owner | Dundee Heritage Trust (since 1985) |

| Builder | Dundee Shipbuilders Company, Dundee |

| Laid down | 1900 |

| Launched | 21 March 1901 |

| Sponsored by | Lady Markham |

| Christened | Lady Markham |

| Status | Museum ship in Dundee, Scotland |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Wooden barque; 1 funnel, 3 masts |

| Tonnage | 736 GRT |

| Displacement | 1,570 tonnes |

| Length | 172 ft (52 m) |

| Beam | 33 ft (10 m) |

| Propulsion | Coal-fired 450 hp (340 kW) steam engine and sail |

| Speed | 8 knots (15 km/h) |

| Crew | 11 officers and 36 men |

The RRS Discovery is a famous ship built in Dundee, Scotland, for exploring the cold lands of Antarctica. Launched in 1901, she was the very last traditional wooden three-masted ship ever built in the United Kingdom. Her first big adventure was the British National Antarctic Expedition. On this trip, she carried famous explorers like Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton on their first successful journey to Antarctica. This journey is known as the Discovery Expedition.

After her first mission, Discovery worked as a merchant ship during World War I. In 1923, the British government took her over for more science work in the Southern Ocean. She became the first official Royal Research Ship. The ship went on a two-year trip called the Discovery Investigations. During this time, she gathered important information about the oceans, sea creatures, and even studied whale populations for the first time. From 1929 to 1931, Discovery was the main ship for the British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE). This was a huge science mission to explore and claim land in what is now the Australian Antarctic Territory.

When she returned from BANZARE, Discovery stayed in London. She was used as a training ship and a place for visitors to explore until 1979. Later, she became a museum ship and was moved back to Dundee in 1986, the city where she was built. After a lot of careful repair work, Discovery is now a main attraction for visitors in Dundee. She is one of only two expedition ships from the exciting Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration that still exists today. The other is the Norwegian ship Fram.

Contents

Building a Ship for Antarctic Adventures

In the late 1800s, many scientists and governments became very interested in Antarctica. This huge continent was mostly unknown. The Royal Navy had explored Antarctica before, discovering the Ross Ice Shelf in 1839. Now, people wanted to send another British expedition to the South Pole.

The British government and the Admiralty agreed to help fund a project. Two main science groups, the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Society, led the effort. The Admiralty helped design the special ship and find a crew. The Royal Geographical Society owned the ship.

Designing a Strong Ship

Early ideas for the ship included copying Fridtjof Nansen's ship Fram. But Fram was built for the icy Arctic. The British ship needed to cross thousands of miles of open ocean to reach Antarctica. So, a more traditional design was chosen. W.E. Smith, a top naval architect from the Admiralty, was in charge of the design. Philip Marrack designed the ship's engine and other machinery.

Smith used ideas from another Dundee-built whaling ship, HMS Discovery, which had been used for an Arctic expedition. By 1900, only a few shipyards in the United Kingdom could build large wooden ships. It was important for the ship to be made of wood. Wood was strong, easy to fix, and didn't interfere with magnetic compasses. This was crucial for accurate navigation and mapping.

The main compass was placed in the middle of the ship. No steel or iron parts were allowed within 30 feet of it. Even the buttons on some cushions had to be changed because they had steel backs! The engine and boilers were placed at the back of the ship. This left more space for equipment and supplies. A special lab was built for measuring magnetic fields.

Building in Dundee

The ship committee thought about having the ship built in Norway. But many believed British money should be spent in a British shipyard. So, the new Discovery was built by the Dundee Shipbuilders Company. This company usually made smaller boats like trawlers and tugboats. They had also built the Terra Nova, which Scott later used for his last expedition.

The Discovery cost about £34,050 to build. The engines and machinery cost another £10,322, and other equipment added over £6000. The total cost was around £51,000, which is like £4.1 million today. Robert Falcon Scott and the ship's engineer, Reginald Skelton, personally oversaw many of the details for fitting out the ship.

Power and Sails

Discovery had a 450-horsepower coal-fired steam engine. But she mostly relied on her sails because she couldn't carry enough coal for very long journeys. At her best speed of 6 knots, she could only steam for about 7,700 nautical miles. The trip to New Zealand was over 12,000 nautical miles!

The ship was mainly a sailing vessel with a steam engine for backup. When first registered in 1900, she was called a sailing ship. She was rigged as a barque, meaning she had square sails on her front and middle masts, and a fore-and-aft sail on her back mast. Her total sail area was huge, about 12,296 square feet. The ship was actually a bit faster under sail than with her engine. She once traveled 223 nautical miles in 24 hours, which is about 9.2 knots.

A Hull Built for Ice

The ship's wooden hull was built incredibly strong to survive being frozen in thick ice. When she was launched, many believed Discovery was the strongest wooden ship ever made. Her hull frames, made of thick oak, were placed very close together. The outer hull had two layers of wood, one 6 inches thick and another 5 inches thick.

A third layer was added inside, making some parts of the hull over 2 feet thick! This made the ship incredibly strong and also kept the crew warm. Because the hull was so thick, there were no portholes. Air and light came in through special 'mushroom vents' on the deck.

Different types of wood were used for different parts of the hull. The inner layer was Scots pine, while the 6-inch skin used pitch pine, Honduras mahogany, or oak. The outer hull was made of English elm and Greenheart. Strong oak beams formed three decks. Seven wooden bulkheads added more strength and helped prevent the whole ship from flooding if ice caused damage.

To protect against ice, the two-blade propeller could be lifted out of the water. The rudder could also be easily removed and stored on board. A spare rudder and propeller blades were carried. The ship's bow was covered in iron and shaped to ride up over ice and crush it.

The ship also had steel compartments on each side that could hold 60 tons of fresh water. For the Antarctic trip, these tanks were filled with extra coal. Ice and snow could be melted daily for water. These metal tanks also made the lower hull stronger around the engine area.

Construction of Discovery began on March 16, 1900. She was launched into the Firth of Tay on March 21, 1901. Lady Markham, wife of Sir Clements Markham, who was president of the Royal Geographical Society, officially launched the ship.

History of the Discovery

First Antarctic Expedition (1901-1904)

The British National Antarctic Expedition left the UK less than five months after Discovery was launched. There wasn't much time to test the ship fully. Her speed under steam was good, reaching 9 knots instead of the planned 8. But her performance under sail was not fully tested.

The long journey to New Zealand, stopping at Madeira and Cape Town, became the ship's real test. Before reaching London, a leak was found near the rudder. There was no time for a full repair, so extra caulking was applied.

The ship loaded supplies in London until July 1901. Then she sailed to Cowes on the Isle of Wight. She was visited by important people, including King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra on August 5. The expedition officially left Cowes the next day, August 6, 1901.

At first, Scott thought the ship was slow and hard to steer. She rolled a lot in the open sea, sometimes by 94 degrees! But once they reached the Roaring Forties, the ship proved to be excellent in rough weather. She was heavy and didn't carry too much sail, so she could make good progress in strong winds. Her rounded stern protected the rudder and kept the decks dry.

The expedition stopped in Lyttelton, New Zealand, for supplies. Here, the ship was put in dry dock for the first time. The carpenter found many problems, including badly sealed joints that had let 6 feet of water into the ship's bilges. These were repaired, and Discovery left for Antarctica on December 21, 1901.

They saw the Antarctic coast on January 8, 1902. Scott spent the first month mapping the coastline. For winter, he anchored in McMurdo Sound. On February 8, Discovery was surrounded by ice. The ship became their home, and a hut on shore was used as a lab. The strong wooden hull protected the ship from the ice.

By late March, Discovery was completely frozen in. She stayed icebound for two years! The crew continued their scientific work. They discovered that Antarctica was a continent and found the South magnetic pole. Scott, Shackleton, and Edward Wilson also reached a new "Furthest South" point.

Discovery was a great place to live, even though the officers' cabins were very cold. Ice often formed on the walls. In January 1903, the relief ship Morning arrived with supplies. Everyone hoped Discovery would break free, but she remained stuck. The crew had to spend a second winter in the ice.

In January 1904, a second relief expedition arrived with Morning and the Terra Nova. They had orders to get everyone out and abandon Discovery if she wasn't free by February 25. The relief ships slowly broke through the ice, and Scott's crew used saws and pickaxes to cut ice around Discovery.

On February 16, 1904, the ice suddenly began to break up. After some controlled explosions, Discovery was free! The relief ships came alongside. Fifty tons of coal were transferred from Terra Nova and 25 tons from Morning.

On February 17, a gale blew up. Discovery dragged her anchor and almost crashed back onto the ice shelf. Scott tried to leave, but the ship ran aground on an unknown shoal. She was stuck for nearly ten hours, being slammed by waves and wind. Scott called it "truly the most dreadful" evening. At 3 AM on February 18, the wind calmed, and the ship slid free. Inspections showed she had almost no damage, only losing some outer wood and minor rudder damage.

With the extra coal, Scott didn't have to go straight back to New Zealand. He explored north, proving some charted land didn't exist. Near Cape Adare, the damaged rudder broke, and the spare had to be fitted. The three ships met at the Auckland Islands and docked in Lyttelton on April 1. Discovery then sailed east, taking ocean measurements and searching for a 'phantom' island. She stopped at the Falkland Islands for magnetic surveys. Discovery arrived back in Spithead on September 10, 1904, after 1131 days away.

Working as a Cargo Ship (1905-1923)

After her famous expedition, Discovery was in financial trouble. In 1905, she was sold to the Hudson's Bay Company for £10,000. This was much less than she cost to build. The company used her as a cargo ship between London and Hudson Bay, Canada. They changed her a lot, removing cabins to make more space for cargo.

From 1905 to 1911, Discovery made yearly trips across the Atlantic. She carried food, fuel, and building materials from London to Canada. On the way back, she was filled with fur hides. Each trip took about two months in the summer. She often had to break through ice in the Davis and Hudson Straights.

In 1912, a new, larger icebreaker replaced Discovery. She was then laid up in London. In 1913, she was almost sold to Joseph Foster Stackhouse for another Antarctic expedition, but he couldn't raise enough money.

World War I and Beyond (1914-1923)

When World War I started, Stackhouse's expedition was put on hold. He died in 1915 when the Lusitania sank. Discovery was then used by the Hudson's Bay Company to carry wartime supplies. She sailed from London to New York, then to French ports, carrying things like caustic soda and corduroy. She had many leaks and mechanical problems.

In 1915, she sailed to Arkhangelsk in Russia, carrying French munitions to help the Russian Empire. This journey was difficult, with more leaks and damage. Her return cargo was methanol, which also caused problems due to her rolling in heavy seas.

In 1916, Discovery was loaned to the British government to rescue Shackleton's party who were stranded on Elephant Island. She was refitted and left on August 11, 1916. But Shackleton's crew rescued themselves before Discovery arrived. To cover costs, Discovery carried a cargo of wheat back to Plymouth.

Between 1917 and 1918, Discovery carried cargo along the French coast. In June 1918, she made her last transatlantic trip, sailing from Cardiff to Charlton Island. She got stuck in ice twice. Her condition was so poor that she couldn't carry valuable furs on the return trip.

In July 1919, the British government used Discovery again. This time, she supported the White Russians in the Russian Civil War. She sailed to ports on the Black Sea, carrying supplies and then cement. She returned to London in March 1920.

After this, Discovery was no longer needed by the Hudson's Bay Company. She was laid up in London, and her equipment was removed. In 1922, she was loaned as a temporary headquarters for the 16th Stepney Sea Scouts.

The Discovery Investigations (1923-1927)

In 1923, Discovery got a new life. The Colonial Office of the British government bought her for more research. They paid £5000. The government wanted to study whale populations in the Southern Ocean.

Discovery underwent a huge £114,000 refit. This was almost like rebuilding her. The Government of the Falkland Islands paid much of the cost. Whaling was very important to their economy, and this research would help manage whale stocks. So, Discovery became owned by the Falkland Islands and was registered in Port Stanley. She was also officially named a Royal Research Ship.

To improve her sailing, her front and middle masts were moved forward. New sails were added to make her faster. A second steering wheel was added on the bridge, connected to a new steam-powered steering engine. Her hull was extensively re-planked, and parts of her keel were replaced. New labs, a library, and cabins were built.

The ship was fitted with special winches for taking soundings and deep-water trawling nets. An early echo sounder was also installed. This allowed her to map the ocean depth and collect samples of the seabed and deep-sea fish. She also got electric lighting and a refrigerated store.

Stanley Wells Kemp led the research, and Joseph Stenhouse became captain. The ship left Portsmouth in July 1925. The refit had been rushed, so she had to stop in Dartmouth for two months of repairs. She finally left on September 24 and reached Cape Town on December 20.

Discovery stopped regularly to take oceanographic surveys. These could take up to six hours each. She reached South Georgia on February 20. For two months, scientists studied whales with whalers. Discovery also mapped the seas around South Georgia.

The ship's rolling and limited engine power made work difficult in the South Atlantic winter. On April 17, 1926, Discovery sailed to the Falkland Islands and then back to Cape Town. She spent three months in dry dock getting bilge keels to improve stability. Some masts were removed to reduce weight and make her steadier.

For the next season, Discovery was joined by a new research steamer, RRS William Scoresby. She returned to South Georgia on December 15. The changes had greatly improved her stability. She studied plankton until February 1927, then went to the South Shetland Islands to 'tag' whales.

In March, Discovery visited Deception Island, a natural harbor for whaling ships. She then explored the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, mapping the area. Discovery Sound was explored and named after the ship. Discovery was the first ship to take oceanographic readings in the stormy Drake Passage. This helped create the first complete map of Antarctic currents. She arrived at Port Stanley on May 6, 1927.

After a final trip to Cape Town, Discovery sailed for Britain, arriving at Falmouth on September 29, 1927. This voyage was called "the most important scientific expedition" since the famous Challenger trip.

The BANZARE Expedition (1929-1931)

In 1926, British leaders discussed claiming more land in Antarctica. At the time, only the Falkland Islands and the Ross Dependency were officially part of the British Empire. Seven other areas could be claimed. An expedition was needed to formalize these claims and do more science. This became the British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE).

The Australian government was in charge, and they chose Discovery as the best ship. The ship was leased to Australia for free. Antarctic veteran Douglas Mawson led BANZARE, and John King Davis became captain of Discovery.

Discovery left London on August 1, 1929. She carried 25 officers and men, scientific equipment, and a small de Havilland DH.60 Moth aircraft for aerial surveys. After loading coal in Cardiff, she sailed to Cape Town, where Mawson and the scientists joined the ship.

Like Scott, Captain Davis was not impressed with Discovery as a sailing ship at first. She was slow in light winds. But in strong winds, she performed well, once traveling at 10 knots. She reached Cape Town on October 5, three days faster than Scott's first voyage.

For the expedition, some yards and topmasts were removed from the mainmast to make the ship more stable. Two new boats were added, along with 40 tons of food, a library, scientific equipment, and over 300 tons of coal. Twelve scientists, including zoologists and a photographer, joined the ship.

Discovery left Cape Town on October 19. She stopped at Île de la Possession, the Kerguelen Islands, and Heard Island to study wildlife and map the areas. The weather was often stormy. On December 8, Discovery reached the Antarctic ice field.

The aircraft, fitted as a seaplane, was used for scouting. It was the first aircraft used in Antarctica. On January 1, 1930, Mawson spotted new land and mountains, named Mac. Robertson Land. On January 13, the first landing was made on Proclamation Island, where the Union Jack flag was planted.

Two days later, Discovery met the Norwegian expedition ship Norvegia. The meeting point, 44°38′E, became the boundary for future Australian and Norwegian territorial claims. After the ships parted, Discovery was caught in a fierce storm, again proving her strength.

Captain Davis worried about coal supplies, leading to disagreements with Mawson, who wanted to continue scientific work. Working eastward, the expedition surveyed Cape Ann. On January 25, Mawson flew over Enderby Land and dropped a second flag.

The next day, Davis said only 120 tons of coal were left, and they had to turn back. Mawson reluctantly agreed. After some oceanographic work, they reached the Kerguelen Islands, took on coal, and cleaned the boilers. Discovery then sailed to Australia, arriving in Adelaide on April 1, 1930.

A second year of research was approved. Mawson remained in command, and Kenneth N. MacKenzie became captain. The second expedition left Hobart on November 22, 1930. She carried 73 tons of supplies, including 20 live sheep, two tons of butter, and 430 tons of coal. With this heavy load, she sat much lower in the water.

On December 1, the ship anchored off Macquarie Island to study wildlife. On December 15, they met a whaling ship and took on 100 tons of coal and 25 tons of fresh water. The expedition headed towards Adélie Land. The summer of 1930 had very heavy ice. On December 31, a violent storm hit, driving the ship against thick ice. For eight hours, Discovery was battered, but MacKenzie managed to get her offshore.

The ship found shelter at Mawson's old base camp at Cape Denison. Here, magnetic field readings were taken, showing the South Magnetic Pole had moved. On January 5, 1931, Mawson claimed the newly surveyed coast as George V Land for the British Empire. Discovery continued westward, with aircraft doing most of the survey work due to heavy ice.

The aerial team found a coastline first seen in 1840 and renamed it the Banzare Coast. Storms often interrupted their work. On February 11, the weather cleared, allowing Discovery to get closer to the coast. This unknown land was named Princess Elizabeth Land, claimed by dropping a flag from the air. The Murray Monolith was discovered and claimed a few days later.

By February 18, only 100 tons of fuel were left, the minimum for the return trip. The next day, the ship was prepared for the ocean crossing. The journey north started with another furious gale. Even with only two sails, Discovery averaged 8.5 knots in waves over 100 feet high. MacKenzie called Discovery "my wonderful little ship." The weather eased, and Discovery arrived back at Hobart on March 19, 1931.

The ship and most of her crew then returned to Britain via Cape Horn, arriving in London on August 1, 1931, exactly two years after she left.

Training Ship in London (1936-1985)

After returning to Britain, Discovery was no longer needed for research. A newer ship, RRS Discovery II, had been launched in 1929. The original Discovery was old and had limitations. She was slow, rolled a lot, and it was hard to find crews experienced in traditional sailing ships.

During the Great Depression, no expeditions could afford to use her. In 1936, she was given to the Boy Scouts Association to be a static training ship for Sea Scouts in London. She was moored near Westminster Bridge.

During the Second World War, Discovery served as a headquarters for the River Emergency Service. In 1941, a barrage balloon got tangled in her main mast, and it was found that the wood was rotten. All her yards and spars were removed. In 1943, her boilers and machinery were taken out. To keep her stable, her lower parts were filled with small rocks. The old engine room became a mess hall, and the boiler room became a classroom.

In 1951, during the Festival of Britain, Discovery hosted an exhibition about Antarctica. In the 1950s, she became too expensive for the Scout Association. In 1954, she was transferred to the Admiralty and became HMS Discovery. She was used as a drill ship for the Royal Naval Reserve and a training ship for the Westminster Sea Cadet Corps.

The Navy refitted her, removing or changing most of her original fittings. In 1960, she became the flagship of the Admiral Commanding, Reserves. She was one of only two sailing ships to fly the White Ensign and an Admiral's flag in the 20th century.

As the wooden ship got older, her condition worsened. In 1979, The Maritime Trust saved her from being scrapped. She became a museum ship and was open to the public. The Maritime Trust spent about £500,000 on repairs. In 1985, she was given to the Dundee Heritage Trust.

Journey Home to Dundee

On March 28, 1986, Discovery left London. She was carried on a special ship called Happy Mariner. She arrived at Victoria Dock on the River Tay on April 3. This was the first time she had been back to Dundee since she was built.

Discovery Point, Dundee

In 1992, Discovery was placed in a custom-built dock. She is now the main attraction at Dundee's visitor center, Discovery Point.

The ship is displayed as close as possible to how she looked in 1923 after her big refit. She is part of the National Historic Fleet. Discovery Point is a highly-rated museum that has won many awards. In 2008, Discovery and her polar collections were recognized as a Collection of National Significance.

Since the 1990s, the museum has focused on all of Discovery's voyages. It shows personal items from the crew and information about her scientific work. You can see games played by the crew, examples of sea creatures, and even Captain Scott's rifle and pipe.

The museum explores Discovery's three main voyages: the National Antarctic Expedition (1901–1904), the Discovery Oceanographic Expedition (1925–1927), and the BANZARE expedition (1929–31). It uses films, photos, and artifacts from each time period. The museum also has items from Scott's later Terra Nova expedition and Shackleton's Endurance expedition.

The ship also appears on the crest of the coat of arms of the British Antarctic Territory.

Other Ships Named Discovery

Three other Royal Research Ships have been named Discovery. The second, RRS Discovery II (built in 1929), and the third, RRS Discovery (built in 1962), are no longer in service. The fourth and current ship is RRS Discovery, built in 2013.

The spaceship Discovery One in Arthur C. Clarke's 1968 book 2001: A Space Odyssey was named after RRS Discovery. Clarke used to eat lunch on her when she was moored near his office in London.

The Space Shuttle Discovery was also named after RRS Discovery, as well as other famous ships like Captain Cook's HMS Discovery and Henry Hudson's Discovery.

See also

In Spanish: RRS Discovery para niños

In Spanish: RRS Discovery para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |