Clements Markham facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Clements Markham

|

|

|---|---|

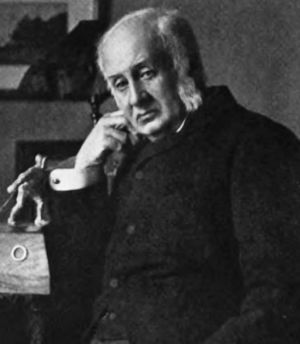

Markham in 1905

|

|

| President of the Royal Geographical Society | |

| In office 29 May 1893 – 22 May 1905 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir Mountstuart Duff |

| Succeeded by | Sir George Goldie |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Clements Robert Markham

20 July 1830 Stillingfleet, York, England |

| Died | 30 January 1916 (aged 85) London, Middlesex, England |

| Spouse |

Minna Chichester

(m. 1857) |

| Parent | David Frederick Markham |

| Relatives | Sir Albert Markham (cousin) |

| Education |

|

| Occupation | Explorer, geographer, writer |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch | Royal Navy |

| Service years | 1844–1852 |

| Rank | Midshipman |

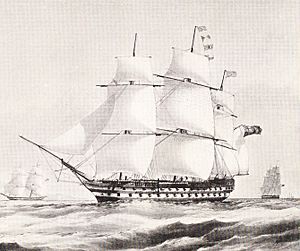

| Ships | Collingwood, Assistance |

| Expeditions | Austin expedition (1850) |

Sir Clements Robert Markham (born July 20, 1830 – died January 30, 1916) was an English geographer, explorer, and writer. He worked for the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) for many years. First, he was its secretary from 1863 to 1888. Later, he became the Society's president for 12 more years.

As president, he helped plan the British National Antarctic Expedition (1901–1904). He also played a big part in starting the polar career of Robert Falcon Scott. Markham began his career in the Royal Navy as a midshipman. He even went to the Arctic to search for the lost expedition of Sir John Franklin.

Later, Markham worked as a geographer for the India Office. He brought cinchona plants from Peru to India. These plants were important because they provided quinine, a medicine for malaria. Markham also joined Sir Robert Napier's trip to Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) in 1868. He was there when the city of Magdala fell.

One of Markham's biggest achievements as RGS president was bringing back British interest in exploring the Antarctic. This happened after about 50 years of no major expeditions. He strongly believed the National Antarctic Expedition should be a naval mission. He wanted it led by Scott, even though many scientists disagreed. After the expedition, he kept supporting Scott's career. He sometimes overlooked what other explorers achieved.

Markham traveled a lot and wrote many books. His writings included histories, travel stories, and biographies. He also wrote many papers for the RGS. He translated and edited many works for the Hakluyt Society, where he also became president. He received many awards for his work in geography. Mount Markham in Antarctica is named after him. Scott named it in 1902.

Contents

Early Life & Education

Clements Markham was born on July 20, 1830, in Stillingfleet, Yorkshire, England. His father, Reverend David Frederick Markham, was a vicar. His family had connections to the royal court. This helped his father become a canon at Windsor.

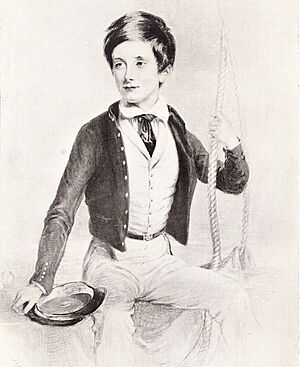

In 1838, his family moved to Great Horkesley. Clements started school at Cheam School and then went to Westminster School. He was a good student and loved geology and astronomy. He also enjoyed writing a lot in his free time. At Westminster, he especially liked boating on the River Thames. He often helped steer boats in races.

In May 1844, Clements Markham met Rear Admiral Sir George Seymour. This meeting led to him joining the Royal Navy as a cadet. On June 28, 1844, Markham joined Seymour's ship, HMS Collingwood. This ship was getting ready for a long trip to the Pacific Ocean.

The journey lasted almost four years. They visited Rio de Janeiro and the Falkland Islands. On December 15, 1844, they reached Valparaíso, Chile. Markham had a comfortable time because of his family's connections. He often ate with the admiral and his family.

After a short break, Collingwood sailed to Callao, Peru. This was Markham's first visit to Peru, a country that would be very important to him later. For the next two years, Collingwood sailed around the Pacific. They visited the Sandwich Islands, Mexico, and Tahiti. In Tahiti, Markham tried to help local rebels against the French.

On June 25, 1846, Markham passed his exam to become a midshipman. He was third out of ten students. He also learned Spanish during his time in Chilean and Peruvian ports. Towards the end of the trip, Markham started to have doubts about a naval career. He wanted to be an explorer and geographer instead.

When he returned to Portsmouth in July 1848, he told his father he wanted to leave the navy. But his father convinced him to stay. He spent months doing nothing, which made him even less interested in the navy. However, in 1850, he heard about a new search for Sir John Franklin's lost Arctic expedition. Markham used his family's influence to join. In April 1850, he was assigned to HMS Assistance.

First Arctic Journey: 1850–1851

Sir John Franklin had left England in May 1845 to find the Northwest Passage. His ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, were last seen in Baffin Bay in July 1845. The search for them began two years later. Markham joined the rescue group led by Captain Horatio Austin. Markham's ship, Assistance, was captained by Erasmus Ommanney.

As the youngest member, Markham had a small role. But he wrote down everything in his journal. The ships sailed on May 4, 1850. They reached Melville Bay on June 25 and were stuck in ice until August 18. Then, they sailed into Lancaster Sound, Franklin's known route.

On August 23, Ommanney found a cairn (a pile of stones) and supplies with "Goldner" written on them. Goldner was Franklin's canned meat supplier. These were the first signs of Franklin's expedition. A few days later, on Beechey Island, they found three graves. These were for Franklin's crew members who died in 1846.

The search continued until the ships had to stop for the long Arctic winter. During this time, the crew had lectures and plays. Markham was very good at acting. He read a lot about Arctic history and thought about returning to Peru. When spring came, they went on sledging trips. Markham joined these trips, but they found no more signs of Franklin. They did map hundreds of miles of new coast. The expedition returned to England in October 1851.

Right after returning, Markham told his father he wanted to leave the navy. He disliked the harsh punishments given for small mistakes. He had even gotten into trouble for trying to stop a crewman from being whipped. He also hated the long periods of doing nothing. His father sadly agreed. After passing an exam, Markham left the navy at the end of 1851.

Journeys to Peru

First Trip to Peru: 1852–1853

In the summer of 1852, Markham planned a long trip to Peru. His father gave him £500 (a lot of money back then) for his expenses. Markham sailed from Liverpool on August 20. He traveled through Halifax, Nova Scotia, then by land to Boston and New York. From there, he took a steamer to Panama. After crossing Panama, he sailed to Callao, Peru, arriving on October 16.

On December 7, 1852, he started his journey into the Peruvian mountains. His goal was the ancient Inca city of Cuzco. On his way, Markham stayed for almost a month in Ayacucho. He studied the local culture and learned more about the Quechua people. He then continued towards Cuzco. He crossed a swinging bridge over the Apurímac River. Finally, he reached Cuzco on March 20, 1853.

Markham stayed in Cuzco for several weeks. He studied Inca history and wrote about the many old buildings he visited. He also went on trips to nearby towns. In the San Miguel area, he first learned about the cinchona plant. This plant was a source of quinine, a medicine. He left Cuzco on May 18, heading back to Lima.

Their journey took them south to Arequipa. This was an old Spanish city with a mix of local and European buildings. The city is overlooked by the volcano Mount Misti. Markham thought it looked like Mount Fuji in Japan. On June 23, they reached Lima. There, Markham learned his father had died. He sailed back to England, arriving on September 17.

The Cinchona Mission: 1859–1861

The idea of bringing cinchona plants to India started in 1813. In 1859, Markham, who worked for the India Office, suggested a plan. He wanted to collect cinchona trees from Peru and Bolivia. Then, he would plant them in India. Cinchona bark was the first known treatment for malaria. His plan was approved, and Markham was put in charge.

Markham and his team left England for Peru in December 1859. They arrived in Lima in January 1860. Their work was dangerous. Peru and Bolivia were close to war. Also, Peruvians who controlled the cinchona trade were not friendly. This made it hard for Markham to get the best plants. But he managed to get the needed export licenses.

Markham returned to England briefly. Then he sailed to India to find good places for cinchona farms. He also looked in Burma (now Myanmar) and Ceylon. Many of the Indian farms failed due to insects. But others survived. They were helped by new plants that were better for India. Twenty years later, India was producing a lot of cinchona bark. For his work, Markham received £3,000 from the British Government. This was a very large sum of money.

Civil Servant, Geographer, & Traveler

Working for the India Office: 1857–1867

After his father died in 1853, Markham needed a job. In December 1853, he got a small job in the Legacy Duty Office. He earned £90 a year. He found the work boring. But after six months, he moved to the India Office in 1857. This new job was interesting. It also gave him time to travel and study geography.

In April 1857, Markham married Minna Chichester. She went with him on the cinchona mission to Peru and India. Their only child, a daughter named Mary Louise, was born in 1859. At the India Office, Markham studied many things. He looked into growing Peruvian cotton in India. He also researched a medicinal plant called ipecacuanha from Brazil. He even studied the future of the pearl industry in India. He also tried to move Brazilian rubber trees to India, but this plan did not work out.

Trip to Abyssinia: 1867–1868

In 1867, Markham was chosen to go with Sir Robert Napier's army to Abyssinia. Markham went as the expedition's geographer. The British government sent this army because the Abyssinian King Theodore had imprisoned British people. The king was upset because the British had not replied to his letters.

Napier's soldiers arrived in Annesley Bay in early 1868. Markham worked with the army's leaders. He helped survey the land and choose the best route to Magdala. Magdala was the king's mountain fortress. Markham also studied the wildlife during their 400-mile march.

He went with Napier to Magdala, which was attacked on April 10, 1868. Markham wrote about the battle. He said the British rifles were too strong for the Abyssinian troops. He noted that King Theodore died as a hero, even though he had done many cruel things. After the battle, Magdala was burned down. Its guns were destroyed, and treasures were taken. Markham returned to England in July 1868. For his help, he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1871.

Second Arctic Journey: 1875–1876

Markham knew many important people. In the early 1870s, he used his connections to ask for a new Royal Navy Arctic expedition. Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli agreed. When the expedition was ready, Markham was invited to go as far as Greenland. He sailed on HMS Alert, one of the expedition's ships. Markham accepted and left on March 29, 1875. He was gone for three months. He stayed with Alert until Disko Island in Baffin Bay.

He wrote that it was a very happy trip with "noble fellows." He returned to England on the support ship HMS Valorous. His long absence from the India Office and his many other interests led his bosses to ask him to resign. Markham retired in 1877, after 22 years of service. He received a pension.

Meanwhile, the main expedition, led by Captain George Nares, went north. They used two ships, HMS Discovery and HMS Alert. On September 1, 1875, they reached 82° 24' North. This was the farthest north any ship had gone at that time. The next spring, Markham's cousin, Commander Albert Hastings Markham, led a sledging team. They reached a new Farthest North record at 83° 20'.

Leading the Royal Geographical Society

Honorary Secretary: 1863–1888

In November 1854, Markham became a member of the Royal Geographical Society. This society became the main focus of his geographical work. In 1863, he was made its honorary secretary. He held this job for 25 years.

Besides promoting the Nares Arctic expedition, Markham also followed other Arctic explorers. In 1880, he organized a party for the Swedish explorer Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld. Nordenskiöld had successfully sailed through the North-East Passage. Markham also kept track of American expeditions. Leaving the India Office gave Markham more time to travel. He often went to Europe. In 1885, he visited America and met President Grover Cleveland.

Throughout his time as secretary, Markham wrote many travel books and biographies. He also wrote many papers for the RGS. He wrote the "Progress of Geographical Discovery" article for the Encyclopædia Britannica. He also wrote popular history books. For the RGS, Markham updated their guide, Hints to Travellers. He also made the journal Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society more lively. Markham also ran the Geographical Magazine from 1872 to 1878.

At the same time, Markham was secretary of the Hakluyt Society until 1886. Then he became its president. For this society, Markham translated many old Spanish travel stories into English. Many of these were about Peru. Later, some scholars questioned how accurate some of his translations were. They thought he did them too quickly. Still, he translated 22 volumes for the society. In 1873, Markham became a Fellow of the Royal Society. He also received awards from other countries. He thought about becoming a politician but decided not to.

Markham stayed interested in the navy, especially in training officers. He often visited training ships like HMS Conway and HMS Worcester. In 1887, he joined his cousin Albert Markham's training squadron in the West Indies. Markham spent three months on the ship HMS Active. On March 1, 1887, he met Robert Falcon Scott for the first time. Scott was a midshipman on another ship. Markham noticed Scott when he won a boat race.

RGS President: 1893–1905

In May 1888, Markham left his job as RGS Secretary. He disagreed with the Society's new focus on education over exploration. When he retired, he received the Society's Founder's Medal. They praised his "incomparable services to the Society."

The next few years, he traveled and wrote a lot. He went on more trips with the training squadron. He also visited the Baltic and the Mediterranean. In 1893, while he was away, Markham was elected president of the society. This was a surprise. It happened because of a disagreement within the Society about allowing women members. Markham had stayed quiet about this issue.

In July 1893, the idea of admitting women was voted on. It was narrowly defeated, even though most members had voted for it by mail. Because of this, the Society's President, Sir M. E. Grant Duff, resigned. The 22 women who were already members could stay. But no new women were allowed until January 1913.

Markham was not the first choice for president. But he had avoided the women's issue, so most members accepted him. Soon after becoming president, he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath. He became Sir Clements Markham.

Markham later said that he felt he needed to "restore the Society's good name" after the women's dispute. He decided to do this by focusing on a big project: Antarctic exploration. No country had explored the Antarctic much since Sir James Clark Ross's trip 50 years before. In 1893, oceanographer John Murray gave a speech to the RGS. He called for an expedition to answer questions about the South Pole. The RGS and the Royal Society formed a committee to push for a British Antarctic expedition.

The National Antarctic Expedition: 1895–1904

Murray's call for Antarctic exploration was repeated in 1895. The RGS hosted the sixth International Geographical Congress. This meeting agreed that exploring the Antarctic was the biggest geographical challenge left. They said it would bring new scientific knowledge. They asked societies worldwide to support this work before the century ended.

The committee planning the British expedition had different ideas. Murray and the Royal Society wanted a civilian expedition, led by scientists. But Markham and most of the RGS wanted a naval expedition. Markham wanted to bring back the glory of naval exploration. Markham finally won. In 1900, he chose his favorite, Robert Falcon Scott, to lead the expedition. Scott was a torpedo lieutenant at the time. Markham stopped a plan to have a professor lead the expedition instead.

Some critics said this meant science was less important than naval adventure. But Markham's instructions for the expedition commander said both geography and science were equally important. The arguments about "science versus adventure" came up again after the expedition. Some of its scientific results were criticized.

Markham also had trouble getting money for the expedition. By 1898, after three years, he had only a small part of the money needed. Meanwhile, explorer Carsten Borchgrevink got £40,000 from a publisher for his own Antarctic trip. Markham was very angry. He thought Borchgrevink was taking money away from his project. He called Borchgrevink "a liar and a fraud."

He was also angry at William Speirs Bruce, a Scottish explorer. Bruce had asked to join Markham's expedition but got no reply. So Bruce got money from a Scottish family and started his own expedition. Markham accused Bruce of trying to "cripple the National Expedition." The Scottish expedition sailed anyway. But Markham remained unforgiving. He used his influence to make sure Bruce's team did not get Polar Medals.

A large private donation and government money finally allowed the National Antarctic Expedition to go ahead. A new ship, the Discovery, was built. A mostly naval crew was chosen, along with a small science team. Discovery sailed on August 5, 1901. King Edward VII inspected the ship, and Markham introduced Scott and the officers. The ship was gone for over three years. They explored a large part of Antarctica and did much scientific work.

The Times newspaper called it "one of the most successful expeditions." But the government largely ignored it. Markham was criticized for allowing a second season in the Antarctic without permission. He then could not raise money for the ship's rescue in 1904. The government had to pay for it.

Later Years

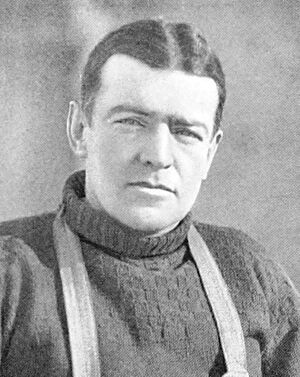

Shackleton and Scott

A few months after the Discovery returned, Markham retired as RGS president. He was 75 years old. He felt his active exploring life was over. He had been president for 12 years, the longest ever. He stayed on the RGS Council and remained interested in Antarctic exploration. He followed the two British expeditions that started after he retired. These were led by Ernest Shackleton and Scott.

Markham had agreed to Shackleton joining the Discovery expedition. He supported Shackleton after he returned early due to illness. He also backed Shackleton's try to join the Royal Navy. Later, when Shackleton planned his own expedition, Markham wrote a strong letter of support. He said Shackleton was "well-fitted to have charge of men in an enterprise involving hardship and peril."

He strongly supported Shackleton's 1907–1909 Nimrod expedition. When he heard Shackleton reached a new Farthest South record, Markham said he would propose Shackleton for the RGS Patron's Medal.

However, Markham changed his mind. He began to doubt Shackleton's claims and told Scott his concerns. Historians think Markham favored Scott and did not want others to get polar fame. Markham became bitter towards Shackleton for the rest of his life. He removed all good comments about Shackleton from his notes. He barely mentioned Shackleton's achievements in a 1912 speech. He also ignored Shackleton in his book The Lands of Silence, published after his death.

In contrast, Markham remained close friends with Scott. He was even godfather to Scott's son, Peter Markham Scott. In his tribute to Scott, Markham called him "among the most remarkable men of our time." Scott, in one of his last letters, wrote: "Tell Sir Clements I thought much of him, and never regretted his putting me in command of the 'Discovery'."

Retirement Activities

After retiring from the RGS presidency, Markham continued to write and travel. He wrote biographies of English kings Edward IV and Richard III. He also wrote about his old navy friend, Admiral Sir Leopold McClintock. He kept editing and translating books. He continued to write papers for the RGS. He remained president of the Hakluyt Society until 1910.

Markham traveled widely in Europe. In 1906, he sailed with the Mediterranean squadron. Scott was a captain on one of the ships. In 1909, Scott announced his new Antarctic trip, the Terra Nova expedition. Markham helped raise money and served on the planning committee. He helped arrange for Lieutenant "Teddy" Evans to be second-in-command.

Markham received honorary degrees from the University of Cambridge and University of Leeds. At Leeds, he was called "a veteran in the service of mankind." He was praised for being "the inspiration of English geographical science for sixty years." However, Markham sometimes caused arguments. In 1912, when Roald Amundsen, who conquered the South Pole, was invited to dine with the RGS, Markham resigned from the council in protest.

Markham heard about the deaths of Scott and his team in February 1913. He was in Estoril at the time. He returned to England and helped prepare Scott's journals for publication. Scott's death was a big shock. But Markham kept writing and traveling. In 1915, he attended a service where a window was dedicated to Scott. Later that year, he helped unveil Scott's statue in London. Markham gave his last paper to the RGS on June 10, 1915. It was about the history of geographical science.

Death and Legacy

On January 29, 1916, Markham was reading in bed by candlelight. The bedclothes caught fire, and he was overcome by smoke. He died the next day. His last diary entry, a few days before, mentioned a visit from Peter Markham Scott.

His family received many tributes. King George V thanked Markham for his life's work. The Royal Geographical Society and other groups also sent messages. So did explorers like Fridtjof Nansen. Messages came from many countries, including Peru.

Later, people looked at Markham's work more critically. Hugh Robert Mill, a historian and RGS librarian, said Markham ran the Society like a dictator. Some of his translations were questioned for being too fast and not accurate enough. He also made enemies. Geologist Frank Debenham called Markham "a dangerous old man." William Speirs Bruce said Markham had "malicious opposition" to his Scottish expedition.

Bruce's colleague, Robert Rudmose-Brown, called Markham "that old fool and humbug." These comments show Markham's strong protection of Scott. Bruce believed Markham thought he had to put Scott first, even if it meant ignoring others. Bruce added that he and Scott were always friends, despite Markham. Markham's writings on naval history have also been criticized. Some say he exaggerated English sailors' achievements.

It is thought that Markham's ideas about polar travel, especially his belief in the "nobility" of pulling sledges by hand, influenced Scott. This might have harmed later British expeditions. Mill's idea that Markham was "an enthusiast rather than a scholar" is a good summary of his strengths and weaknesses. It also explains his influence on geography in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Markham is remembered by Mount Markham, a mountain in Antarctica. Scott discovered and named it in 1902. The Markham River in Papua New Guinea is also named after him. Carsten Borchgrevink named Markham Island in the Ross Sea after him in 1900. In Lima, Peru, there is a school called Markham College. Minna Bluff, a landform in Antarctica, was named by Scott for Lady Markham. The plant group Markhamia was named after him in 1863.

Markham's estate was valued at £7,740. He was survived by his wife, Minna. His only child, May, avoided public life. She worked for the church in London. She died in 1926.

Portrayal in Media

Clements Markham was played by actor Geoffrey Chater in the 1983 BBC TV show Shackleton.

Writings

Markham wrote a lot. His first book, about his Arctic journey, came out in 1853. After he retired in 1877, writing became his main way to earn money. Besides papers for the Royal Geographical Society, he wrote histories, biographies, and travel books. He also translated many works from Spanish to English. He even created a grammar and dictionary for the Quechua language of Peru.

Here are some of his books:

- Franklin's Footsteps (1852)

- Cuzco ... and Lima (1856)

- Travels in Peru and India (1862)

- Contribution Toward a Grammar and Dictionary of Quichua (1864)

- A History of the Abyssinian Expedition (1869)

- A Life of the Great Lord Fairfax (1870)

- Ollanta: an ancient Ynca drama (1871)

- A memoir of the Lady Ana de Osorio, countess of Chinchon and vice-queen of Peru (A. D. 1629–39) with a plea for the correct spelling of the Chinchona genus (1874)

- General Sketch of the History of Persia (1874)

- The Threshold of the Unknown Regions(1875)

- Narrative of the mission of George Bogle to Tibet (1877)

- A Memoir of the Indian Surveys (1878)

- Peruvian Bark (1880)

- The Voyages of William Baffin, 1612–1622 (1881)

- The War between Peru and Chile, 1879–1882 (1882)

- A narrative of the life of Admiral John Markham (1883)

- The Sea Fathers (1885)

- Life of Robert Fairfax of Steeton, Vice-admiral (1885)

- The Fighting Veres (1888)

- The Life of John Davis the Navigator (1889)

- The Life of Christopher Columbus (1892)

- The History of Peru (1892)

- Major James Rennel and the Rise of Modern English Geography (1895)

- The paladins of Edwin the Great (1896)

- Richard III: his life and character (1906)

- The Story of Minorca and Majorca (1909)

- The Incas of Peru (1912)

- The Lands of Silence (completed by F.H.H. Guillemard, 1921)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Clements R. Markham para niños

In Spanish: Clements R. Markham para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |