Terra Nova Expedition facts for kids

The Terra Nova Expedition, also known as the British Antarctic Expedition, was a journey to Antarctica between 1910 and 1913. It was led by Captain Robert Falcon Scott. The expedition had two main goals: to do important scientific research and to be the first to reach the geographic South Pole.

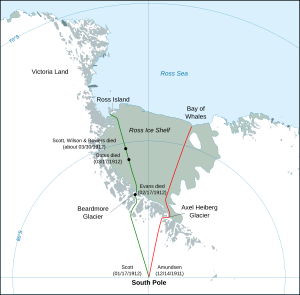

Scott and four friends reached the South Pole on January 17, 1912. However, they discovered that a Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen had arrived 34 days earlier. Sadly, Scott's group of five died on their way back from the Pole. A search party found some of their bodies, diaries, and photos eight months later.

The expedition was named after its supply ship, the Terra Nova. It was a private project, funded by public donations and some money from the government. The British Admiralty (the navy) helped by letting experienced sailors join. The Royal Geographical Society also supported the trip. Scientists on the expedition did a lot of research. Other groups explored Victoria Land and the Western Mountains. They tried to land and explore King Edward VII Land, but it didn't work out. A trip to Cape Crozier in June and July 1911 was the first long sledging journey ever made in the middle of the Antarctic winter.

For many years after Scott's death, people saw him as a sad hero. Few questioned why his polar team faced such a disaster. But in the late 1900s, people looked more closely at the expedition. They started to question how it was planned and managed. It is still debated how much Scott was to blame, and more recently, how much other team members were responsible.

Contents

Preparing for the Journey

Why Scott Returned to Antarctica

After his ship, the RRS Discovery, came back from Antarctica in 1904, Captain Robert Falcon Scott went back to his navy job. But he still dreamed of going south again. His main goal was to conquer the South Pole. His first trip, the Discovery Expedition, had taught the world a lot about Antarctic science and geography. But they had only reached 82° 17' South and had not crossed the huge Great Ice Barrier.

In 1909, Scott heard that Ernest Shackleton's Nimrod expedition had almost reached the Pole. Shackleton had started from a base near Scott's old spot in McMurdo Sound. He crossed the Great Ice Barrier, found the Beardmore Glacier route to the Polar Plateau, and headed for the Pole. He had to turn back at 88° 23' S, less than 100 geographical miles (about 185 km) from his goal. Scott felt that McMurdo Sound was his "field of work." Shackleton using it broke a promise he had made to Scott. This made relations between the two explorers difficult. It also made Scott even more determined to do better than Shackleton.

As Scott got ready for his new expedition, he knew about other trips planned for the Pole. A Japanese expedition was being prepared. The Australasian Antarctic Expedition under Douglas Mawson was leaving in 1911, but it would work in a different part of the continent. And Roald Amundsen, a possible rival from Norway, had also announced plans for an Arctic journey.

Who Joined the Team?

The Terra Nova Expedition had 65 men, including replacements, for both the shore and ship teams. They were chosen from 8,000 people who applied! Seven men had been on Scott's Discovery trip, and five had been with Shackleton. Lieutenant Edward Evans was Scott's second-in-command. He had been a navigating officer on the Morning, a ship that helped Scott's first expedition. Evans had planned his own trip but decided to join Scott instead.

Other navy officers joined, like Lieutenant Harry Pennell, who would navigate the Terra Nova. Two navy doctors, George Murray Levick and Edward L. Atkinson, also came along. Victor Campbell, nicknamed "The Wicked Mate," was good at skiing. He was chosen to lead the group exploring King Edward VII Land. Two non-navy officers were Henry Robertson Bowers ("Birdie") from the Indian Marine, and Lawrence Oates ("Titus"), an Army captain. Oates was wealthy and gave £1,000 to the expedition, plus his own help.

The navy also provided many sailors. These included Antarctic veterans Edgar Evans (not related to Edward Evans), Tom Crean, and William Lashly. Other sailors were Patrick Keohane, Robert Forde, Thomas Clissold (the cook), and Frederick Hooper (the steward). Two foreign members also landed: Dimitri Gerov, a Russian dog driver, and Anton Omelchenko, a Ukrainian groom.

Edward Wilson was the chief scientist. He was Scott's closest friend on the trip. On the Discovery Expedition, Wilson had gone with Scott on the Farthest South march. He was a doctor, a zoologist (animal scientist), and a great artist. Scott's biographer, David Crane, said Wilson's science team was "as impressive a group of scientists as had ever been on a polar expedition." This team included meteorologist George Simpson, physicist Charles Wright, and geologists Frank Debenham and Raymond Priestley. Other members were geologist T. Griffith Taylor, biologists Edward W. Nelson and Denis G. Lillie, and assistant zoologist Apsley Cherry-Garrard.

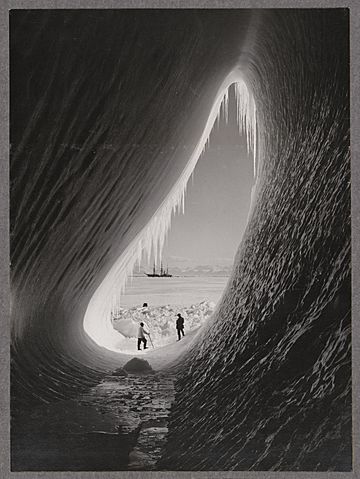

Cherry-Garrard had no science training but was a friend of Wilson's. Like Oates, he gave £1,000 to the expedition. Scott first turned him down, but Cherry-Garrard still let his money stay with the expedition. This impressed Scott, who then changed his mind. Crane called Cherry-Garrard "the future interpreter, historian and conscience of the expedition." Herbert Ponting was the expedition's photographer. His pictures give us a clear look at the journey. Scott also hired a young Norwegian ski expert, Tryggve Gran, after advice from explorer Fridtjof Nansen.

How They Traveled

Scott decided to use a mix of transport methods: dogs, motor sledges, and ponies. He put Cecil Meares in charge of the dog teams. Bernard Day, who had worked with Shackleton's motors, was in charge of the motor sledges. Oates was supposed to manage the ponies, but he couldn't join until May 1910. So Scott told Meares, who knew nothing about horses, to buy them. This led to problems with the ponies' quality and how well they performed.

Shackleton had tried a "polarised" motor car on his 1907–1909 trip, but it didn't work well. However, his use of ponies helped him get as far as the Beardmore Glacier. Scott thought ponies had worked for Shackleton. He also believed he could solve the motor problem by creating a tracked snow "motor," which was like an early Snowcat or tank. Scott always planned to use man-hauling (pulling sledges themselves) on the Polar Plateau. He thought it was impossible to climb the Beardmore Glacier with motors or animals. The motors and animals would only carry heavy loads across the Barrier. This would save the men's strength for the later Glacier and Plateau parts of the journey. In reality, the motor sledges were only useful for a short time. The ponies didn't perform well because they were old and not in good shape. Scott had doubts about dogs from his Discovery trip, but he knew they could be effective if handled well. As the expedition went on, he became more and more impressed with what dogs could do.

Paying for the Trip

Unlike the Discovery Expedition, which got money from the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), the Terra Nova Expedition was a private project. It didn't have much support from big organizations. Scott thought the trip would cost £40,000. The government eventually paid half of this. The rest was raised by public donations and loans. Many companies also helped by giving food and equipment for free. Scott spent a lot of time and energy raising money. He continued fundraising in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand even after the Terra Nova had left Britain.

The biggest cost was buying the ship Terra Nova for £12,500. The Terra Nova had been to Antarctica before, helping with the second Discovery rescue. Scott wanted to sail her as a navy ship. To do this, he joined the Royal Yacht Squadron for £100. This allowed him to run the expedition with navy rules. As a registered yacht, the Terra Nova didn't have to follow some Board of Trade rules that might have said she wasn't fit to sail.

What They Hoped to Achieve

Scott explained the expedition's main goals in his first public appeal: "The main objective of this expedition is to reach the South Pole, and to secure for the British Empire the honour of this achievement." But there were other goals too, both scientific and geographical. Wilson, the chief scientist, thought the science work was the most important part. He said, "No one can say that it will have only been a Pole-hunt... We want the scientific work to make the bagging of the Pole merely an item in the results." He wanted to continue studying the emperor penguin colony at Cape Crozier, which he had started on the Discovery Expedition. He also planned to do a lot of geology, magnetic, and weather studies. There were also plans to explore King Edward VII Land and Victoria Land.

First Season: 1910–1911

Journey to Antarctica

The Terra Nova sailed from Cardiff on June 15, 1910. Scott, who was busy with expedition matters, sailed later on a faster passenger ship and met the Terra Nova in South Africa. In Melbourne, he left the ship to continue fundraising while the ship went to New Zealand. In Melbourne, Scott received a telegram from Amundsen. It said the Norwegian was "proceeding south." This was the first time Scott knew he was in a race. When reporters asked for his reaction, Scott said his plans wouldn't change. He would not give up the expedition's science goals just to win the race to the Pole. In his diary, he wrote that Amundsen had a good chance and probably deserved to succeed if he did.

Scott rejoined the Terra Nova in New Zealand. More supplies were loaded, including 34 dogs, 19 Siberian ponies, and three motorized sledges. The ship was very heavy when it finally left Port Chalmers on November 29. In early December, a big storm hit the ship. At one point, the ship was taking on a lot of water, and the pumps had broken. The crew had to bail water out with buckets. The storm caused the loss of two ponies, one dog, 10 tons of coal, and 65 gallons (295 liters) of petrol. On December 10, the Terra Nova met the southern pack ice and got stuck for 20 days. This delay, which Scott blamed on "sheer bad luck," used up 6.1 tons of coal.

Setting Up Base at Cape Evans

The Terra Nova arrived at Ross Island on January 4, 1911. They looked for places to land near Cape Crozier on the east side of the island. Then they went to McMurdo Sound on the west, where both the Discovery and Nimrod had landed before.

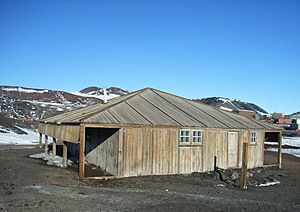

Scott looked at different places to spend the winter. He chose a cape he remembered from the Discovery days, called the "Skuary." It was about 15 miles (24 km) north of Scott's 1902 base at Hut Point. Scott hoped this spot, which he renamed Cape Evans after his second-in-command, would be free of ice in the short Antarctic summer. This would let the ship come and go easily. As the seas to the south froze, the expedition would have easy access over the ice to Hut Point and the Barrier.

At Cape Evans, the shore parties got off the ship. They brought the ponies, dogs, three motorized sledges (one was lost during unloading), and most of the supplies. Scott was "astonished at the strength of the ponies" as they moved supplies from the ship to shore. A pre-made hut, 50 by 25 feet (15 by 7.6 meters), was put up and ready to live in by January 18.

Amundsen's Discovery

Scott's plan included exploring and doing science work in King Edward VII Land, east of the Barrier. A group led by Campbell was set up for this. If King Edward VII Land was too hard to reach, they could explore Victoria Land to the north-west. On January 26, Campbell's group left on the ship and headed east. After several tries to land his group on King Edward VII Land, Campbell decided to sail to Victoria Land. On its way back west along the edge of the Barrier, the Terra Nova found Amundsen's expedition camped in the Bay of Whales, an inlet in the Barrier.

Amundsen was friendly and welcoming. He offered Campbell help with his dogs and was fine with Campbell camping nearby. Campbell politely said no and returned with his group to Cape Evans to tell Scott what had happened. Scott heard the news on February 22, during his first trip to set up supply depots. Cherry-Garrard said Scott and his group first wanted to rush to the Bay of Whales and "have it out" with Amundsen. But Scott wrote calmly in his diary: "One thing only fixes itself in my mind. The proper, as well as the wiser, course is for us to proceed exactly as though this had not happened. To go forward and do our best for the honour of our country without fear or panic."

Setting Up Supply Depots

The goal of the first season's depot-laying was to place supply points on the Barrier. These would go from its edge (Safety Camp) down to 80°S. They would be used for the polar journey starting the next spring. The last depot would be the biggest, called One Ton Depot. Twelve men, the eight strongest ponies, and two dog teams were to do this work. Ice conditions stopped them from using the motor sledges.

The journey started on January 27, "in a state of hurry bordering on panic," according to Cherry-Garrard. They moved slower than expected. The ponies didn't perform well because Oates didn't want to use Norwegian snowshoes and had left them at Cape Evans. On February 4, the group set up Corner Camp, 40 miles (64 km) from Hut Point. A blizzard kept them there for three days.

A few days later, after they started marching again, Scott sent the three weakest ponies back home (two died on the way). As the depot-laying group got close to 80°, Scott worried that the remaining ponies wouldn't make it back to base unless they turned north right away. Oates wanted to keep going, killing the ponies for meat as they collapsed. But Scott decided to put One Ton Depot at 79°29′S, more than 30 miles (48 km) short of where it was planned.

Scott returned to Safety Camp with the dogs. He risked his own life to save a dog-team that had fallen into a crevasse. When the slower pony group arrived, one animal was very sick and died soon after. Later, as the remaining ponies crossed the sea ice near Hut Point, the ice broke. Despite a strong rescue attempt, three more ponies died. Out of the eight ponies that started the depot-laying journey, only two made it back.

Winter Life at Base Camp

On April 23, the sun set for the winter months, and the group settled into the Cape Evans hut. Scott ran the hut like a navy ship. The hut was divided by a wall made of packing cases. Officers and men lived mostly separate lives. Scientists were considered "officers." Everyone stayed busy. Science work continued, observations and measurements were taken, and equipment was fixed for future trips. The remaining ponies needed daily exercise, and the dogs needed regular care. Scott spent a lot of time figuring out food and weights for the polar march. Their routine included regular talks on many topics: Ponting on Japan, Wilson on drawing, Oates on managing horses, and geologist Debenham on volcanoes.

To stay fit, they often played football in the dim light outside the hut. Scott wrote that, "Atkinson is by far the best player, but Hooper, P.O. Evans and Crean are also quite good." The South Polar Times, a newspaper Shackleton had made on the Discovery Expedition, was brought back. Cherry-Garrard was the editor. On June 6, they had a big meal for Scott's 43rd birthday. A second celebration on June 21 marked Midwinter Day, the middle of the long polar night.

Main Journeys: 1911–1912

Northern Party's Adventures

After telling Scott about Amundsen's arrival at Cape Evans, Campbell's Eastern party (Campbell, Priestley, Levick, George P. Abbott, Harry Dickason, and Frank V. Browning) became the "Northern Party." On February 9, 1911, they sailed north. They reached Robertson Bay, near Cape Adare, on February 17. There, they built a hut close to Norwegian explorer Carstens Borchgrevink's old camp.

The Northern Party spent the winter of 1911 in their hut. They couldn't fully carry out their exploration plans for the summer of 1911–1912. This was partly because of the sea ice and because they couldn't find a way into the land. The Terra Nova returned from New Zealand on January 4, 1912. It moved the party to Evans Cove, about 250 miles (400 km) south of Cape Adare and 200 miles (320 km) northwest of Cape Evans. They were supposed to be picked up on February 18 after finishing more geology work. But heavy pack ice stopped the ship from reaching them. The group had very little food. They had to eat fish and seal meat to survive. They were forced to spend the winter of 1912 in a snow cave they dug on Inexpressible Island. Here, they suffered greatly from frostbite, dysentery, and hunger. They also faced extreme winds and low temperatures, and the discomfort of a blubber stove in a small space.

On April 17, 1912, a group led by Atkinson (who was in charge at Cape Evans while the polar party was away) went to rescue Campbell's party. But bad weather forced them back. The Northern Party survived the winter in their icy cave. They set out for the base camp on September 30, 1912. Even though they were physically weak, the whole group managed to reach Cape Evans on November 7. They had a dangerous journey, including crossing the difficult Drygalski Ice Tongue. The Terra Nova picked up the rocks and other samples collected by the Northern Party from Cape Adare and Evans Cove in January 1913.

Western Geology Trips

First Geology Trip: January–March 1911

This trip aimed to explore the geology of the coast west of McMurdo Sound. This area was between the McMurdo Dry Valleys and the Koettlitz Glacier. A group with Taylor, Debenham, Wright, and Edgar Evans did this work. They landed from the Terra Nova on January 26 at Butter Point, across from Cape Evans on the Victoria Land shore. On January 30, the group set up their main supply point in the Ferrar Glacier area. Then they explored and mapped the Dry Valley and Taylor Glacier areas. After that, they moved south to the Koettlitz Glacier. After more work there, they started heading home on March 2. They took a southern route to Hut Point, arriving on March 14.

Second Geology Trip: November 1911 – February 1912

This trip continued the work from the earlier journey. This time, they focused on the Granite Harbour region, about 50 miles (80 km) north of Butter Point. Taylor's companions this time were Debenham, Gran, and Forde. The main journey started on November 14. It involved difficult travel over sea ice to Granite Harbour, which they reached on November 26. They set up their headquarters at a place they called Geology Point and built a stone hut. In the following weeks, they explored and mapped the Mackay Glacier. They also found and named many features north of the glacier.

The Terra Nova was supposed to pick up the group on January 15, 1912, but the ship couldn't reach them. The group waited until February 5 before walking south. They were finally rescued from the ice when the ship spotted them on February 18. The Terra Nova picked up the rock samples from both Western Mountains expeditions in January 1913.

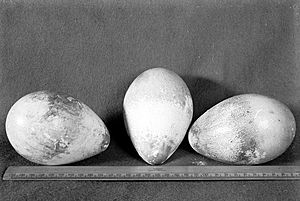

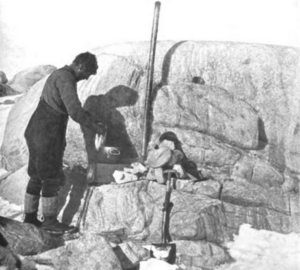

Winter Journey to Cape Crozier

Wilson came up with this journey. He had suggested it in the science reports from the Discovery Expedition and wanted to continue his earlier research. The trip's science goal was to get emperor penguin eggs from the colony near Cape Crozier at an early stage of development. This would allow scientists to study how the birds developed. This meant a trip in the middle of winter to get eggs at the right time. A second goal was to test food and equipment before the polar journey that summer. Scott approved, and a group of Wilson, Bowers, and Cherry-Garrard set out on June 27, 1911.

No one had ever traveled in the Antarctic winter before. Scott wrote that it was "a bold venture, but the right men have gone to attempt it." Cherry-Garrard later described how terrible the 19 days were to travel the 60 miles (97 km) to Cape Crozier. Their gear, clothes, and sleeping bags were always covered in ice. On July 5, the temperature dropped below -77°F (-61°C). Cherry-Garrard wrote it was "109 degrees of frost—as cold as anyone would want to endure in darkness and iced up clothes." Often, they traveled little more than one mile a day.

After reaching Cape Crozier on July 15, the group built an igloo from snow blocks, stone, and a wooden sheet they brought for the roof. They then visited the penguin colony and collected several emperor penguin eggs. Later, a blizzard with winds of force 11 on the Beaufort scale almost destroyed their igloo. The storm also blew away their tent, which they needed to survive the return journey. Luckily, they found it half a mile away. The group started their return journey to Cape Evans, arriving on August 1. The three eggs that survived the trip first went to the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. After that, Cossar Stewart at the University of Edinburgh wrote a report about them. The eggs did not support Wilson's ideas.

Cherry-Garrard later called this the "worst journey in the world." He used this as the title of the book he wrote about the expedition. Scott called the Winter Journey "a very wonderful performance." He was very happy with the tests of food and equipment, saying, "We are as near perfection as experience can direct."

The South Pole Journey

Across the Barrier: Heading South

Scott, Bowers, Wilson, and Edgar Evans at Amundsen's base at the South Pole

|

|

| Leader | Robert Falcon Scott |

|---|---|

| Start | Cape Evans base 1 November 1911 |

| End | 11 mi (18 km) S of One Ton Depot 29 March 1912 |

| Goal | First to reach the South Pole |

| Crew |

|

| Fatalities | 5 |

| Route | |

Scott's route compared to Amundsen's |

|

On September 13, 1911, Scott told his team his plans for the South Pole march. Sixteen men would start. They would use the two remaining motor sledges, ponies, and dogs for the Barrier part of the journey. This would take them to the Beardmore Glacier. At this point, the dogs would return to base, and the ponies would be killed for food. After that, 12 men in three groups would climb the glacier and start crossing the polar plateau, pulling the sledges themselves. Only one of these groups would continue to the Pole. The other groups would be sent back at certain points. Scott would decide who would be in the final polar group during the journey. For the return trip, Scott ordered that the dog teams leave the base camp again. They were to restock supply depots and meet the polar party between 82° and 82°30' latitude on March 1 to help them get home.

The motor party, including Lieutenant Evans, Day, Lashly, and Hooper, started from Cape Evans on October 24. They had two motor sledges. Their goal was to pull loads to 80° 30' S and wait there for the others. By November 1, both motor sledges had broken down after traveling little more than 50 miles (80 km). So, the party pulled 740 pounds (336 kg) of supplies themselves for the remaining 150 miles (240 km). They reached their assigned latitude two weeks later. Scott's main party, which had left Cape Evans on November 1 with the dogs and ponies, caught up with them on November 21.

Scott's first plan was for the dogs to return to base at this stage. But because they were moving slower than expected, he decided to take the dogs further. Day and Hooper were sent back to Cape Evans with a message for Simpson, who was in charge there. On December 4, the expedition reached the Gateway. This was the name Shackleton gave to the route from the Barrier onto the Beardmore Glacier. At this point, a blizzard hit, forcing the men to camp until December 9. They had to start using food meant for the Glacier journey. When the blizzard stopped, the remaining ponies were shot as planned. Their meat was left as food for the groups returning later. On December 11, Meares and Dimitri turned back with the dogs. They carried a message back to base saying that "things were not as rosy as they might be, but we keep our spirits up and say the luck must turn."

Climbing the Beardmore Glacier

The group started climbing the Beardmore. On December 20, they reached the start of the polar plateau. There, they set up the Upper Glacier Depot. Scott still hadn't hinted who would be in the final polar party. On December 22, at 85° 20' S, Scott made his decision. Atkinson, Cherry-Garrard, Wright, and Keohane would return. Scott reminded Atkinson "to take the two dog-teams south in the event of Meares having to return home, as seemed likely" to help the polar party on its way back the following March.

The remaining eight men continued south. Conditions were better, which helped them make up some time lost on the Barrier. By December 30, they were on Shackleton's 1908–1909 schedule. On January 3, 1912, at 87° 32' S, Scott decided who would go to the Pole: five men (Scott, Wilson, Oates, Bowers, and Edgar Evans) would go forward. Lieutenant Evans, Lashly, and Crean would return to Cape Evans. The decision to take five men meant they had to recalculate weights and food, as everything had been planned for four-man teams.

Reaching the South Pole

The polar group kept going towards the Pole. They passed Shackleton's Farthest South (88° 23' S) on January 9. Seven days later, about 15 miles (24 km) from their goal, they saw Amundsen's black flag. The party knew they had been beaten. They reached the Pole the next day, January 17: "The Pole. Yes, but under very different circumstances from those expected... Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority. Well, it is something to have got here."

Scott still hoped to race Amundsen to the telegraph cable in Australia: "Now for a desperate struggle to get the news through first. I wonder if we can do it." On January 18, they found Amundsen's tent, some supplies, a letter to King Haakon VII of Norway (which Amundsen politely asked Scott to deliver), and a note saying Amundsen had arrived there with four friends on December 14, 1911.

The Last March

After confirming their location and planting their flag, Scott's party turned for home. For the next three weeks, they made good progress. Scott's diary noted several "excellent marches." Still, Scott started to worry about his team's physical state, especially Edgar Evans. Evans was suffering from severe frostbite and was, Scott wrote, "a good deal run down." The condition of Oates's feet became a growing concern as the group neared the top of the Beardmore Glacier and got ready to go down to the Barrier. On February 7, they began their descent. They had serious trouble finding a supply depot. During a short period of good weather, Scott ordered a half-day's rest. This allowed Wilson to "geologise" (study rocks). Thirty pounds (14 kg) of fossil-filled samples were added to the sledges. These plant fossils later helped support the idea of continental drift. Evans's health was getting worse. A hand injury wasn't healing, he had bad frostbite, and he might have hurt his head after several falls on the ice. "He is absolutely changed from his normal self-reliant self," Scott wrote. Near the bottom of the glacier, Evans collapsed and died on February 17.

On the Barrier part of the march home, Scott reached the 82° 30' S meeting point for the dog teams, three days early. He wrote in his diary for February 27, 1912: "We are naturally always discussing possibility of meeting dogs, where and when, etc. It is a critical position. We may find ourselves in safety at the next depot, but there is a horrid element of doubt." The party then faced three major problems: the dog teams didn't appear, the temperature dropped unexpectedly low, and there was not enough fuel in the supply depots. The low temperatures created bad surfaces that Scott compared to "pulling over desert sand." He described the surface as "coated with a thin layer of woolly crystals, formed by radiation no doubt. These are too firmly fixed to be removed by the wind and cause impossible friction on the [sledge] runners." The low temperatures also meant there was no wind, which Scott had expected to help them on their journey north.

The party was also slowed down by frostbite in Oates's left foot. Daily marches were now less than 5 miles (8 km), which was not enough given the lack of oil. By March 10, it became clear the dog teams were not coming: "The dogs which would have been our salvation have evidently failed. Meares [the dog-driver] had a bad trip home I suppose." In a farewell letter to Sir Edgar Speyer, dated March 16, Scott wondered if he had gone past the meeting point. He fought the growing feeling that the dog teams had left them. "We very nearly came through, and it's a pity to have missed it, but lately I have felt that we have overshot our mark. No-one is to blame and I hope no attempt will be made to suggest that we had lacked support." On the same day, Oates, whose "hands as well as feet [were] pretty well useless," chose to leave the tent, knowing it meant he would not survive. Scott wrote that Oates's last words were, "I am just going outside and may be some time."

Eleven Miles from Safety

Oates's sacrifice made the team move faster, but it was too late to save them. Scott's right toes were now getting frostbitten. Scott, Wilson, and Bowers struggled on to a point 11 miles (18 km) south of One Ton Depot. But they were stopped on March 20 by a fierce blizzard. Although they tried to move forward each day, they couldn't. Scott's last diary entry, dated March 29, 1912 (the likely date of their deaths), ends with these words:

Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity but I do not think I can write more. R. Scott. Last entry. For God's sake look after our people.

Attempts to Help the Polar Party, 1912

Orders for Dog Teams

Before starting the South Pole journey, Scott had made plans to help the polar party return using dogs. Meares, who was expected back at Cape Evans by December 19, was told that in late December or early January he should take supplies to One Ton Depot. These supplies included "Five XS rations [Extra Summit Ration, food for four men for one week], 3 cases of biscuit, 5 gallons of oil and as much dog food as you can conveniently carry." If dogs couldn't do this, then a man-hauling team had to carry the XS rations to the depot "at all hazard." Meares was also told that around the first week of February, depending on news from returning groups, he should set out with dogs. His goal was to meet the returning polar party between latitudes 82° or 82°30' around March 1. The purpose of these orders was to get the party back to Cape Evans quickly before the Terra Nova left. This way, news of reaching the Pole could be sent to New Zealand right away. Scott thought the second journey (meeting the polar party) was more important than the first (supplying One Ton Depot). He said, "Whilst the object of your third journey is important, that of the second is vital." Atkinson was reminded of these orders when he left Scott at the top of the Beardmore Glacier on December 22, 1911.

Several things happened that made these orders unclear and eventually stopped them from being carried out. Meares turned back from the polar march much later than planned. He didn't return to Cape Evans until January 5. Some suggest he quit because he was "disgusted" with Scott's expedition. However, Fiennes quotes a letter from Cherry-Garrard in 1938. It said Meares was ready at Cape Evans to resupply One Ton Depot as ordered. But he thought he saw the ship arrive in the bay and so stayed at base. This "ship" turned out to be a mirage, and the real ship didn't arrive until mid-February. According to Fiennes, Meares was busy with his late father's estate and wanted to leave on the ship as soon as possible. Three of the XS rations needed for One Ton Depot had been pulled there by men who left Cape Evans on December 26. But neither Meares nor anyone else brought the missing rations or dog food to One Ton Depot.

Atkinson's Stopped Journey to Meet Scott

When Atkinson returned to Cape Evans from the Beardmore Glacier at the end of January, he was the highest-ranking officer there. So, he was in charge of the base camp, a role he wasn't used to. The Terra Nova arrived from its winter spot in New Zealand on February 9. Instead of leaving to find Scott, Atkinson used the shore party for the hard job of unloading the ship. Cherry-Garrard thought this was a mistake, as these men might be needed for sledging again. Finally, on February 13, Atkinson set out with Dimitri Gerov and the dog teams. They were going to meet Scott on the Barrier as planned. They reached Hut Point 13 miles (21 km) south before bad weather delayed them.

During the journey of the last returning party, Lieutenant Evans had become very sick with scurvy. After One Ton Depot, he couldn't walk. Crean and Lashly carried him on the sledge to a point 35 miles (56 km) south of Hut Point. At that point, he seemed likely to die. On February 18, Crean walked alone to reach Hut Point. He covered 35 miles (56 km) of difficult land in only 18 hours. There, he found Atkinson and Dimitri with their dogs, pausing on their journey to meet Scott. Atkinson changed his focus to rescuing Evans. He brought Evans to Hut Point, barely alive, on February 22. From then on, Atkinson's main goal was to get Evans safely to the ship.

Cherry-Garrard's Trip to One Ton Depot

With Atkinson busy, another plan to pick up Scott was needed. Meares was "not available for work." The most qualified person to meet Scott's party was the physicist Wright. He was an experienced traveler and navigator. But the chief scientist Simpson insisted Wright's science work was more important. So Atkinson chose Cherry-Garrard. Lieutenant Evans later wrote that he thought Scott would have approved the decision to keep Wright at the base camp. Cherry-Garrard would be joined by Dimitri.

In his 1922 book The Worst Journey, Cherry-Garrard remembered the controversial verbal orders Atkinson gave him. He was to travel to One Ton Depot as fast as possible. There, he was to leave food for the returning polar party. If Scott had not arrived before him, Cherry-Garrard should decide "what to do." Atkinson also stressed that this was not a rescue party. He added that Scott had given instructions that the dogs were "not to be risked in view of the sledging plans for next season." In the regular edition of his book, Cherry-Garrard didn't mention Scott's request to be picked up at 82° or 82°30' on March 1. But after Atkinson's and Lady Scott's deaths in 1929 and 1947, in a postscript to his privately published 1948 edition, Cherry-Garrard admitted Scott's order existed. He gave reasons why Atkinson, and later he himself, didn't follow it. Atkinson was too tired in early February to leave to meet Scott. Also, there was not enough dog food at One Ton Depot to start on time. Karen May of the Scott Polar Research Institute suggests that the instruction about saving the dogs for the next season was Atkinson's own idea.

Cherry-Garrard left Hut Point with Dimitri and two dog teams on February 26. They arrived at One Ton Depot on March 4 and left the extra food. Scott was not there. With supplies for themselves and the dogs for 24 days, they had about eight days before they had to return to Hut Point. The choice was to wait or move south for another four days. Any travel beyond that, without the dog food depot, would mean killing dogs for food as they went. This would break Atkinson's "not to be risked" order. Cherry-Garrard argued that the weather was too bad for more travel, with daytime temperatures as low as -37°F (-38°C). He also thought he might miss Scott if he left the depot. So he decided to wait for Scott. On March 10, with worsening weather and his own supplies running low, Cherry-Garrard turned for home. Meanwhile, Scott's team was fighting for their lives less than 70 miles (110 km) away. Atkinson would later write, "I am satisfied that no other officer of the expedition could have done better." Cherry-Garrard was troubled for the rest of his life, thinking he might have done something different to save the polar party.

Atkinson's Last Rescue Attempt

When Cherry-Garrard returned from One Ton Depot without Scott's party, worries grew. Atkinson, now in charge at Cape Evans as the highest-ranking naval officer present, decided to try again to reach the polar party when the weather allowed. On March 26, he set out with Keohane, pulling a sledge with 18 days' worth of food. In very cold temperatures (-40°F/-40°C), they reached Corner Camp by March 30. At that point, Atkinson felt the weather, the cold, and the time of year made it impossible to go further south. Atkinson wrote, "In my own mind I was morally certain that the [polar] party had perished."

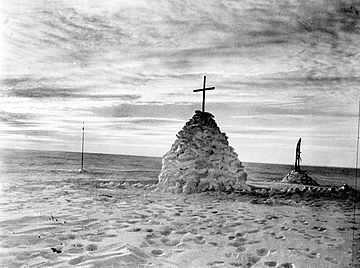

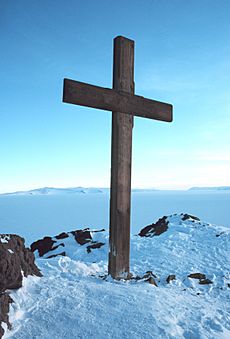

Search Party, October 1912

The remaining expedition members at Cape Evans waited through the winter, continuing their science work. In the spring, Atkinson had to decide whether to first rescue Campbell's Northern Party or find out what happened to the polar party. A meeting of the whole group decided they should first search for signs of Scott. The party set out on October 29. They were joined by a team of mules that had been brought from the Terra Nova during its supply visit the previous summer. On November 12, the party found the tent with the frozen bodies of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers, 11 miles (18 km) south of One Ton Depot. Atkinson read parts of Scott's diaries, and the details of the disaster became clear. After collecting diaries, personal items, and records, the tent was collapsed over the bodies. A cairn (a pile of stones) of snow was built, topped by a cross made from Gran's skis. The party searched further south for Oates's body, but only found his sleeping bag. On November 15, they built a cairn near where they believed he had died.

When they returned to Hut Point on November 25, the search party found that the Northern Party had rescued themselves and returned safely to base. Early on February 10, 1913, Atkinson and Pennell rowed into the New Zealand port of Oamaru. From there, they sent a coded message to the expedition's New Zealand agent, Joseph Kinsey, telling him what happened to Scott and his party. Atkinson and Pennell then took a train to meet the Terra Nova in Lyttelton near Christchurch.

After the Expedition

The loss of Scott and his party overshadowed everything else for the British public. This included Amundsen's success in being first at the Pole. For many years, Scott was seen as a tragic hero, beyond criticism. Even though there were disagreements among some people close to the expedition, these were not made public. Public opinion didn't really change until the 1970s, by which time almost everyone directly involved with the expedition had passed away.

Controversy started with the publication of Roland Huntford's book Scott and Amundsen (1979, later shown on TV in 1985 as The Last Place on Earth). Huntford criticized Scott's leadership style and his poor judgment of people. He blamed Scott for a series of organizational failures that led to the deaths of everyone in the polar party. Scott's public image suffered from these attacks. Efforts to restore his reputation include Ranulph Fiennes's account (which directly disagreed with Huntford's version), Susan Solomon's scientific study of the weather conditions that ultimately defeated Scott, David Cranes's 2005 biography of Scott, and Karen May's new look at Scott's disobeyed orders about the dog teams.

When comparing Scott's and Amundsen's achievements, most polar historians agree that Amundsen's skills with skis and dogs, his knowledge of ice conditions, and his clear focus on a non-scientific expedition gave him big advantages in the race for the Pole. Scott's own thoughts on the disaster, written when he was close to death, list several problems. These include the early loss of pony transport, bad weather, "a shortage of fuel in our depots for which I cannot account," and Evans and Oates getting sick. But Scott finally concluded that "our wreck is certainly due to this sudden advent of severe weather... on the Barrier... -30°F (-34°C) in the day, -47°F (-44°C) at night." Regarding the dog teams not meeting them on March 1, 1912, Scott wrote, "No-one is to blame and I hope no attempt will be made to suggest that we have lacked support." Cherry-Garrard, whom Atkinson put in charge of the dog teams that started late and didn't meet Scott, noted that "the whole business simply bristles with 'ifs'." He meant that many decisions and situations could have turned out differently, but they all led to the disaster. Still, he said, "we were as wise as anyone can be before the event."

After being badly damaged while carrying supplies to bases in Greenland, the Terra Nova was set on fire and later sunk by gunfire off the southern coast of Greenland on September 13, 1943, at 60°15′15″N 45°55′45″W / 60.25417°N 45.92917°W. Its remains were found underwater in 2012.

Scientific Discoveries

The scientific contributions of the expedition were for a long time overshadowed by the deaths of Scott and his party. The 12 scientists who took part—the largest Antarctic science team of its time—made important discoveries in zoology (animal science), botany (plant science), geology (earth science), glaciology (ice science), and meteorology (weather science). The Terra Nova returned to England with over 2,100 plants, animals, and fossils. More than 400 of these were new to science. Discoveries of the fossil plant Glossopteris—also found in Australia, New Zealand, Africa, and India—supported the idea that Antarctica's climate used to be warm enough for trees. It also showed that Antarctica was once connected to other landmasses. Before this expedition, glaciers had only been studied in Europe. The weather data collected was the longest continuous weather record in the early 1900s. This data helps us understand climate change today. In 1920, former Terra Nova geographer Frank Debenham and geologist Raymond Priestley founded the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge. This institute now holds the largest collection of polar research.

See also

- Comparison of the Amundsen and Scott Expeditions

- Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

- List of Antarctic expeditions

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |