Henry Robertson Bowers facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Robertson Bowers

|

|

|---|---|

Bowers (seated, left) at the South Pole, January 1912

|

|

| Born | July 29, 1883 |

| Died | March 29, 1912 (aged 28) Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica

|

| Known for | Part of the Terra Nova expedition |

Henry Robertson Bowers (born 29 July 1883 – died around 29 March 1912) was a brave explorer who joined Robert Falcon Scott's famous Terra Nova expedition to Antarctica. This journey, from 1910 to 1913, aimed to reach the South Pole. Sadly, Henry and the rest of Scott's team died on their way back from the Pole.

Contents

Early Life and Adventures

Henry Bowers was born in Greenock, Scotland, on 29 July 1883. His father was a naval captain, but he died when Henry was only three years old. Henry's mother raised him and his two older sisters by herself. The family later moved to Streatham in South London.

Henry started his sea adventures as a cadet, training on a ship called HMS Worcester. He sailed around the world four times! In 1905, he joined the Royal Indian Marine Service. He became a sub-lieutenant and worked in places like Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Burma (now Myanmar). He even commanded a river gunboat on the Irrawaddy River. Later, he served on HMS Fox, helping to stop illegal gun trading in the Persian Gulf.

Joining the Terra Nova Expedition

Henry Bowers joined Robert Falcon Scott's Terra Nova expedition in 1910. He had read about Scott's earlier Discovery expedition and Ernest Shackleton's journey. Even though Henry had no experience in polar regions, a respected explorer named Sir Clements Markham recommended him to Scott. Scott was so impressed that he invited Henry to join without even an interview!

At first, Scott wasn't too sure about Henry. Henry was short and stout, and he even fell into a ship's hold while loading supplies. But Scott soon changed his mind. Henry was originally meant to be a junior officer in charge of ship supplies. However, he quickly showed how hardworking and organized he was. By the time the Terra Nova left New Zealand, Scott had promoted him. Henry became a key member of the shore party, managing supplies, navigation, and food for sledging trips. His amazing memory was a great help to Scott.

The Winter Journey to Cape Crozier

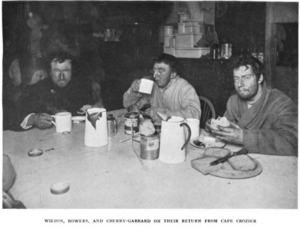

Six months after arriving in Antarctica, Henry took part in a very tough winter journey. In July 1911, he traveled to the emperor penguin breeding grounds at Cape Crozier with Edward Adrian Wilson and Apsley Cherry-Garrard. Their goal was to collect an unhatched penguin egg for science.

It was almost completely dark, and temperatures dropped to a freezing −40 to −70 °F (−40 to −57 °C). They pulled their sledge 60 miles (97 km) from Scott's base at Cape Evans across Ross Island. They were frozen and exhausted when they reached their goal. Then, a terrible blizzard hit. Their tent was ripped away by the wind, leaving them in their sleeping bags under a growing pile of snow. Luckily, they found their tent later, stuck in some rocks.

After successfully collecting three eggs, they were completely worn out. They finally returned to Cape Evans on 1 August 1911, five weeks after they started. Cherry-Garrard later called this trip The Worst Journey in the World. This became the title of his famous book about the expedition.

The Race to the South Pole

On 1 November 1911, the long journey to the South Pole began. Scott had not originally planned for Henry to be in his final polar team. Henry was part of a support team led by Lieutenant Edward Evans, 1st Baron Mountevans. But on 4 January 1912, just as Evans's group was about to turn back, Scott added Henry to the polar party.

Some people think this was a sudden decision by Scott. However, others, like explorer Ranulph Fiennes, believe it made sense. Adding Henry, who was very strong, could help them travel faster.

Just days before, Scott had told Evans's men to leave their skis behind. This meant Henry had to walk to the Pole while the others were still on skis. Also, adding a fifth person meant squeezing into a tent made for four and splitting up food meant for four men. Scott likely added Henry because he needed another skilled navigator. Henry could confirm their exact location at the South Pole. This was important to avoid arguments, like those about who reached the North Pole first. Henry was the one who took the measurements to find the exact spot of the South Pole. He also took most of the famous photos at the Pole and at Amundsen's tent.

On 16 January 1912, as Scott's team got close to the Pole, Henry was the first to spot a black flag. It was left by Roald Amundsen's polar party over a month earlier. They knew then that they had lost the race to be first to the South Pole. On 18 January, they reached the South Pole. They found a tent left by Amundsen's team. Inside, a note said Amundsen had reached the Pole on 14 December 1911. He had beaten Scott's party by 35 days.

The Return Journey and Legacy

On the way back, the team faced terrible conditions. P.O. Edgar Evans died on 17 February. By the end of February, temperatures dropped sharply. The dog team that was supposed to meet them with supplies did not show up. Oates's foot became severely frostbitten, slowing them down. In a brave attempt to save his friends, Oates walked out of their tent to his death on 16 March.

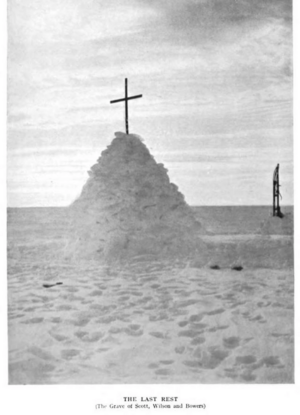

Scott, Henry Bowers, and Wilson continued for three more days, traveling another 20 miles (32 km). But they were stopped 11 miles (18 km) short of their next food depot by a blizzard on 20 March. The blizzard lasted for days, longer than they had fuel and food. Too weak, cold, and hungry to go on, they died in their tent on or soon after 29 March. This was 148 miles (238 km) from their base camp.

A search party found their bodies the following spring on 12 November 1912. The searchers collapsed the tent over them, burying them under a snow pile with a cross made from skis. They found Henry's camera film with the photos from the South Pole. They also found geological rock samples. These samples later helped prove the Gondwana theory, which explains how continents move.

The Bowers Hills in Antarctica, later renamed the Bowers Mountains, were named in Henry's honor.

Character and Nickname

Henry Bowers was short, about five feet four inches tall. He had red hair and a distinctive nose that looked like a bird's beak. This quickly earned him the nickname "Birdie" among his fellow explorers. He was known for being tough, reliable, and always cheerful.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, who was on the expedition with him, said that Henry's "capacity for work was prodigious" (meaning he could do an amazing amount of work). He also said Henry was "transparently simple, straightforward, and unselfish." Scott wrote in his diary that Henry was "the hardest traveller that ever undertook a Polar journey as well as one of the most undaunted."

In a letter to Henry's mother, found in the tent where they died, Scott wrote: "I write when we are very near the end of our journey, and I am finishing it in company with two gallant, noble gentlemen. One of these is your son. He had come to be one of my closest and soundest friends, and I appreciate his wonderful upright nature, his ability and energy. As the troubles have thickened his dauntless spirit ever shone brighter and he has remained cheerful, hopeful, and indomitable to the end."

Archives

Henry Bowers's life is remembered with a small display at Rothesay Museum on the Isle of Bute. His mother and sister lived there, and he loved visiting them and walking in the Scottish Highlands. Copies of the photographs Henry took on the last part of the South Pole journey were shown widely during the 100-year anniversary of the expedition. These photos are kept at the Scott Polar Research Institute and other archives.

See also

In Spanish: Henry Robertson Bowers para niños

In Spanish: Henry Robertson Bowers para niños

- List of solved missing person cases

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |