Apsley Cherry-Garrard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Apsley Cherry-Garrard

|

|

|---|---|

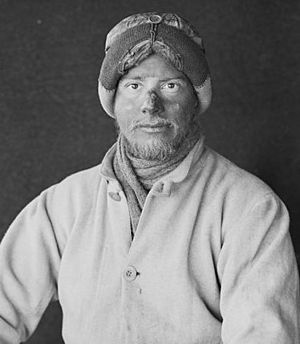

Cherry-Garrard in January 1912

|

|

| Born |

Apsley George Benet Cherry

2 January 1886 Bedford, Bedfordshire, England

|

| Died | 18 May 1959 (aged 73) Piccadilly, London, England

|

| Education | |

| Occupation | Zoologist, explorer, author |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | Royal Naval Reserve |

| Service years | 1914–1916 |

| Wars | World War I |

Apsley George Benet Cherry-Garrard (born January 2, 1886 – died May 18, 1959) was an English explorer who traveled to Antarctica. He was part of the famous Terra Nova Expedition and is well-known for his book, The Worst Journey in the World, which he wrote in 1922 about his experiences.

Contents

A Young Explorer's Start

Apsley George Benet Cherry was born in Bedford, England. He was the oldest child of Apsley Cherry and Evelyn Edith. He went to Winchester College and then to Christ Church, Oxford University, where he studied old languages and modern history. While at Oxford, he was a strong rower and his team won a big race called the Grand Challenge Cup in 1908.

His last name changed to Cherry-Garrard because of his great-aunt's will. His father inherited a large estate called Lamer Park, and Apsley inherited it when his father died in 1907.

Apsley always admired his father's brave stories from fighting in India and China with the British Army. He wanted to do something just as important. In 1907, he met Robert Falcon Scott and Edward Adrian Wilson, who were planning another trip to Antarctica. Apsley decided to join them.

Adventures in Antarctica

At 24 years old, 'Cherry' was one of the youngest members of the Terra Nova expedition. This was Scott's second and last trip to Antarctica. Cherry-Garrard first tried to join the expedition, but Scott said no because he wanted scientists. Cherry-Garrard tried again and offered to donate GB£1,000 (equivalent to £73,000 in 2021) to help pay for the trip.

Scott was impressed by this generous offer and by what Edward Adrian Wilson said about Cherry-Garrard. So, Scott agreed to let him join as an assistant zoologist, someone who studies animals. The expedition arrived in Antarctica on January 4, 1911. For the next few months, Cherry-Garrard helped set up supply points with food and fuel along the path the team would take to reach the South Pole.

The Winter Journey

In July 1911, during the Antarctic winter, Cherry-Garrard went on a special trip with Wilson and Henry Robertson Bowers. They traveled to Cape Crozier on Ross Island to collect unhatched emperor penguin eggs. Scientists hoped these eggs would help prove how all birds are related to reptiles. Cherry-Garrard had very bad eyesight and could barely see without his glasses, which he couldn't wear while pulling the sledge.

It was almost completely dark, and temperatures were incredibly cold, from −40 to −77.5 °F (−40.0 to −60.8 °C). They pulled their sledge 60 miles (100 km) from Scott's base at Cape Evans to the other side of Ross Island. They had two sledges, but the ice was so rough and the cold so extreme that they couldn't pull both at once. They had to "relay," meaning they would pull one sledge a certain distance, then go back for the other. This made them walk three miles (4.8 km) for every one mile they moved forward. Sometimes, they only traveled a couple of miles a day.

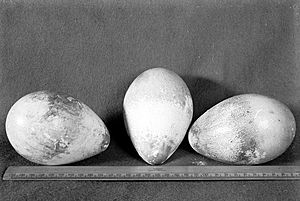

After 19 days, frozen and tired, they reached their goal. They built a simple shelter from rocks and canvas near the penguin colony. They managed to collect three penguin eggs. Then, a huge blizzard, a very strong snowstorm, hit on July 22. It tore their tent away and blew it far off. The roof of their rock shelter also blew away the next day. The men were left in their sleeping bags, covered in snow, singing songs to keep their spirits up.

When the storm finally stopped on July 24, they were incredibly lucky to find their tent stuck in a snowdrift half a mile away. Cherry-Garrard was so cold that his teeth chattered so hard they broke. Exhausted and sleep-deprived, they left everything they didn't need and started their journey back. Some days they only moved a mile and a half. They finally got back to Cape Evans just before midnight on August 1. Cherry-Garrard later called this trip "the worst journey in the world," a name suggested by his friend George Bernard Shaw. He used this title for his book about the expedition.

The Polar Journey

On November 1, 1911, Cherry-Garrard joined the team that would try to reach the South Pole. He went with three other groups, who used men, dogs, and horses to carry supplies. At the bottom of the Beardmore Glacier, the horses were killed for food, and the dog teams went back to base. At the top of the Beardmore Glacier, on December 22, Cherry-Garrard was in the second support group sent back. He arrived at base on January 26, 1912.

One Ton Depot

Scott had given instructions for dog handler Meares and doctor Edward L. Atkinson to take the dog teams south in early February 1912. They were supposed to meet Scott's group on March 1 at a certain latitude and help them on their way back. But Meares was not available, Atkinson had a medical emergency, and George Simpson was busy. So, Cherry-Garrard was chosen for this important task. On February 26, 1912, Cherry-Garrard and dog handler Dimitri Gerov finally headed south. They reached One Ton Depot on March 3 and left more food there.

They waited there for seven days, hoping to meet Scott's South Pole team. Cherry-Garrard and Dimitri then turned back on March 10. Scott's team was only 55 miles (89 km) (about three days' dog travel) south of One Ton Depot at that time. Scott and his companions eventually died from starvation or freezing, just 11 miles (18 km) south of One Ton Depot. Cherry-Garrard later wrote that their main goal was to help Scott's team get home, not to rescue them.

He explained his decision to wait a week and then turn back. He said the terrible weather, with temperatures as low as −37 °F (−38 °C) during the day, made it impossible to go further south. Also, they didn't have enough dog food, and he would have had to kill dogs for food, which Atkinson had told him not to do. They returned to base on March 16 without Scott's team, which made everyone worried about Scott's fate.

Two days later, Cherry-Garrard fainted and was sick for several days. Atkinson then went to look for Scott, but on March 30, he had to turn back because of the extreme cold. He realized that Scott's team must have died.

The Search Journey

Cherry-Garrard was later put in charge of keeping records and continued his animal studies. The scientific work went on through the winter. It wasn't until October 1912 that a team led by Atkinson, including Cherry-Garrard, could go south to find out what happened to the South Pole team.

On November 12, they found the bodies of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers in their tent. They also found their diaries, records, and rock samples they had brought back from the mountains. Cherry-Garrard was very sad, especially about the deaths of Wilson and Bowers, who had been with him on the difficult trip to Cape Crozier.

Later Life

After returning home in February 1913, Cherry-Garrard went with Edward Atkinson to China. Atkinson was investigating a type of parasitic worm that was making British sailors sick. When World War I started, Cherry-Garrard, with his mother and sisters, turned his family estate, Lamer, into a hospital for wounded soldiers. In August 1914, Cherry-Garrard went to Belgium with Major Edwin Richardson, a dog trainer. He helped with a group of bloodhounds that were trained to find wounded soldiers. Cherry-Garrard volunteered because he had experience handling dogs in Antarctica.

After this, Cherry-Garrard returned to England. He joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and led a group of armored cars in Flanders. In 1916, he had to leave the military because of his health. He suffered from depression and a stomach illness that started after his Antarctica trip. At the time, doctors didn't know about what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder.

Even though his mental health problems were never fully cured, writing about his experiences helped him. He spent many years sick in bed. He also needed a lot of dental work because the extreme cold had damaged his teeth. He often thought about what could have been done differently to save the South Pole team. He wrote about these thoughts in his 1922 book, The Worst Journey in the World.

On September 6, 1939, Cherry-Garrard married Angela Katherine Turner. They had no children. After World War II, his poor health and taxes forced him to sell his family estate. He moved to a flat in London, where he died in Piccadilly on May 18, 1959. He is buried in the churchyard of St Helen's Church, Wheathampstead.

His Writings

In 1922, with encouragement from his friend George Bernard Shaw, Cherry-Garrard wrote The Worst Journey in the World. More than 80 years later, this book is still being printed. It is often called a classic of travel literature and one of the greatest true adventure stories ever written. It was the 100th book published by Penguin Books. When the book first came out, some people criticized Cherry-Garrard for describing Scott's negative qualities, because Scott was still seen as a hero in Britain after the war. One critic wrote that Cherry-Garrard "resolved to say what he thinks and emphasize the 'heroism' of the story as little as possible."

Cherry-Garrard also wrote an essay remembering T. E. Lawrence for a book edited by Lawrence's brother. In this essay, Cherry-Garrard suggested that Lawrence did amazing things because he felt insecure and needed to prove himself. He also thought that writing, both Lawrence's and his own, helped them deal with the emotional stress of the events they described.

His Legacy

The rock shelter (igloo) that Cherry-Garrard and his team built on Cape Crozier was found by another expedition in 1957–1958. Only about 18 to 24 inches (46 to 61 cm) of the stone walls were still standing. Items found there were taken to museums in New Zealand.

The three penguin eggs that Cherry-Garrard brought back from Cape Crozier are now kept at the Natural History Museum, London.

See also

In Spanish: Apsley Cherry-Garrard para niños

In Spanish: Apsley Cherry-Garrard para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |