William Speirs Bruce facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Speirs Bruce

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 1 August 1867 London, England

|

| Died | 28 October 1921 (aged 54) Edinburgh, Scotland

|

| Resting place | Ashes scattered in the South Atlantic Ocean off the southern shores of South Georgia |

| Nationality | British |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Education | Norfolk County School, University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Naturalist, polar scientist and explorer |

| Spouse(s) | Jessie Bruce, née Mackenzie |

| Children | Eillium Alastair Bruce and Sheila Mackenzie Bruce |

| Parent(s) | Samuel Noble Bruce and Mary Bruce, née Lloyd |

William Speirs Bruce FRSE (1 August 1867 – 28 October 1921) was a British naturalist and oceanographer. He was also a polar scientist and explorer. Bruce led the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE) from 1902 to 1904. This trip went to the South Orkney Islands and the Weddell Sea. A big achievement was setting up the first permanent weather station in Antarctica.

After this, Bruce started the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory in Edinburgh. He had plans for a long walk across Antarctica to the South Pole. But these plans did not happen because he could not get enough public or money support.

In 1892, Bruce stopped his medical studies at the University of Edinburgh. He joined the Dundee Whaling Expedition to Antarctica as a science helper. After this, he went on Arctic trips to places like Novaya Zemlya and Spitsbergen. By 1899, Bruce was Britain's most experienced polar scientist. He wanted to join Robert Falcon Scott's Discovery Expedition. But delays and disagreements led him to start his own Scottish expedition instead. This made some important people in London unhappy with him.

Bruce received many awards for his polar work. He even got an honorary degree from the University of Aberdeen. However, neither he nor his team from the Scottish expedition received the special Polar Medal. This medal was given to other British polar explorers. Between 1907 and 1920, Bruce made many more trips to the Arctic. He went for both science and business. He did not lead any big explorations after his Antarctic trip. This was often because he was not good at public relations. He also had powerful enemies and was very proud of being Scottish. By 1919, his health was getting worse. He died in 1921 and was mostly forgotten for a long time. In recent years, people have started to recognize his important role in polar science.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in London

William Speirs Bruce was born in London on August 1, 1867. He was the fourth child of Samuel Noble Bruce, a Scottish doctor, and Mary Bruce, who was Welsh. His middle name, Speirs, was spelled in an unusual way. This often caused problems for people writing about him. William spent his early years in London. His grandfather taught him at home. They often visited Kensington Gardens and the Natural History Museum. His father said these trips first made William interested in nature.

In 1879, when William was 12, he went to a boarding school called Norfolk County School. He stayed there until 1885. Then he spent two more years at University College School in Hampstead. He was preparing for an exam to get into medical school at University College London (UCL). He passed the exam on his third try and was ready to start medical studies in 1887.

Studying in Edinburgh

In mid-1887, Bruce went to Edinburgh for summer science courses. These six-week courses were at the Scottish Marine Station in Granton. They taught about botany (plants) and zoology (animals). Bruce loved his time at Granton. He met important scientists there. This made him decide to stay in Scotland. He left his spot at UCL and joined the medical school at the University of Edinburgh.

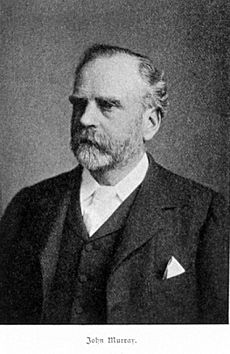

This allowed him to keep working with his teachers. He also worked in Edinburgh labs. Here, scientists were studying specimens from the Challenger expedition. He worked under Dr John Murray. Bruce learned a lot about oceanography and how to do scientific research.

First Journeys to the Poles

The Dundee Whaling Trip

The Dundee Whaling Expedition happened in 1892–93. Its goal was to see if whaling in Antarctic waters could be profitable. They hoped to find right whales. The expedition also planned to do science research. Four whaling ships were used. Bruce was suggested for the expedition by a friend. He quickly joined the Balaena ship as a science helper. The ships left Dundee on September 6, 1892.

The trip was short, and Bruce was back in Scotland by May 1893. It did not find many whales. To save money, the ships hunted many seals for their skins and oil. Bruce did not like this, especially having to help with the killing. He felt the scientific work was poor. He wrote that the ship's captain did not help with science. Bruce could not get maps and was often busy with other tasks. Many specimens were lost because the crew was careless. But Bruce still felt the trip was "instructive and delightful." He wanted to go south again. He soon suggested a science trip to South Georgia, but it did not get support.

Arctic Adventures

From 1895 to 1896, Bruce worked at a weather station on Ben Nevis. This gave him more experience with science tools. In 1896, he joined the Jackson–Harmsworth Expedition in the Arctic. This trip was exploring Franz Josef Land. Bruce sailed on the expedition ship Windward.

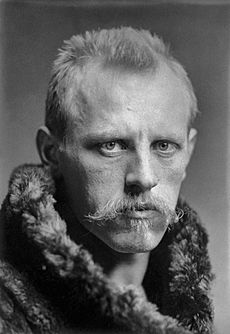

On July 25, the ship arrived at Cape Flora. Bruce met Fridtjof Nansen there. Nansen was a famous Norwegian explorer. He and his friend had been living on the ice for over a year. Meeting Nansen was a lucky chance for Bruce. Nansen later gave Bruce much advice.

During his year at Cape Flora, Bruce collected about 700 animal specimens. He often worked in very cold conditions. The expedition leader, Frederick Jackson, praised Bruce's hard work. Jackson named Cape Bruce after him. But Jackson was not happy that Bruce kept his own specimens instead of giving them to the British Museum. This showed Bruce could be stubborn and not always easy to work with.

More Arctic Trips

After returning from Franz Josef Land in 1897, Bruce worked in Edinburgh. In 1898, he joined Major Andrew Coats on a hunting trip to the Arctic. They sailed on the yacht Blencathra to Novaya Zemlya and Spitsbergen. Bruce took many science measurements on this trip. He checked weather, sea temperature, and water saltiness.

Blencathra tried to sail to Spitsbergen but was stopped by ice. They returned to Norway. There, Bruce met Albert I, Prince of Monaco, a famous oceanographer. Prince Albert invited Bruce to join his research ship, Princesse Alice. Bruce was very happy. He helped with sea surveys around Spitsbergen. He was later put in charge of the science observations.

The next year, Bruce joined Prince Albert again on another trip to Spitsbergen. Bruce climbed the highest peak in the area. The Prince named it "Ben Nevis" after Bruce's earlier work. During this trip, the ship got stuck on a rock. Prince Albert told Bruce to get ready for a winter camp. Luckily, the ship got free and could return for repairs.

Family Life

It is not clear what Bruce did for work after his 1899 Spitsbergen trip. He rarely had a steady job. He usually relied on friends or important people to find him temporary work. In 1901, he felt confident enough to get married. His wife was Jessie Mackenzie, a nurse who had worked for his father. They married on January 20, 1901. Not much is known about their wedding, as Bruce was a private person.

In 1907, the Bruces moved to a house in Joppa, near Edinburgh. They named their house "Antarctica." Their son, Eillium Alastair, was born in April 1902. Their daughter, Sheila Mackenzie, was born seven years later. During these years, Bruce also started the Scottish Ski Club and was its first president. He also helped start Edinburgh Zoo.

Bruce's life as an explorer meant he was often away. His income was not always steady. These things put a lot of stress on his marriage. He and Jessie became distant around 1916. But they continued to live in the same house until Bruce died. Their son, Eillium, became a Merchant Navy officer. He later captained a research ship that, by chance, was named Scotia.

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

Disagreement with Markham

On March 15, 1899, Bruce wrote to Sir Clements Markham. Markham was the head of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS). Bruce offered to join the science team for the National Antarctic Expedition. Markham sent a short reply and Bruce heard nothing for a year. Then he was told to apply for a science assistant job.

On March 21, 1900, Bruce reminded Markham about his earlier application. He also said he hoped to get enough money for a second British ship. A few days later, he said the money for a second ship was sure. This was the first time he spoke about a "Scottish Expedition." Markham was upset. He said a second ship was not needed and that Bruce's plan would hurt the main expedition.

Bruce replied that the money he raised in Scotland would not have been given for any other project. He said he was not trying to compete. Markham wrote back, saying Bruce was "crippling the National Expedition" to start his own. Bruce formally replied that the Scottish funds were only for his plans. They did not write to each other much after this. Markham later sent a short, friendly note, but his actions still showed he was not happy about the Scottish expedition.

The Scotia Voyage

With money from the Coats family, Bruce bought a Norwegian whaling ship. He changed it into a research ship and named it Scotia. He hired an all-Scottish crew and science team. Scotia left Troon on November 2, 1902. It sailed south to Antarctica. Bruce wanted to set up a winter base in the Weddell Sea. On February 22, 1903, the ship reached 70°25′S. But heavy ice stopped them from going further.

They went to Laurie Island in the South Orkney Islands. They spent the winter there in a bay Bruce named Scotia Bay. They built a meteorological station called Omond House. This was part of a full science program.

In November 1903, Scotia went to Buenos Aires for repairs and supplies. In Argentina, Bruce made a deal with the government. Omond House became a permanent weather station under Argentinian control. It was renamed Orcadas Base. This station has been working ever since. It provides the longest weather records for Antarctica.

In January 1904, Scotia sailed south again to explore the Weddell Sea. On March 6, they saw new land. Bruce named it Coats Land after the people who gave money for the expedition. On March 14, the ship was at 74°01′S. It was in danger of getting stuck in the ice. So, Scotia turned north. The long trip back to Scotland, by way of Cape Town, ended on July 21, 1904.

This expedition collected many animal, sea, and plant specimens. It also made many measurements of the sea, magnets, and weather. One hundred years later, people realized the expedition's work helped start "modern climate change studies." Its work showed this part of the world is very important to Earth's climate. The oceanographer Tony Rice said it did more science than any other Antarctic trip of its time. But in Britain, the expedition did not get much attention. Bruce found it hard to get money to publish his science results. He blamed Markham for the lack of national recognition.

After the Expedition

Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory

Bruce had collected many specimens from his trips. He needed a place for them. He also needed a base to write the science reports from the Scotia voyage. He found a building in Edinburgh. There, he set up a lab and museum. He called it the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory. He hoped it would become the Scottish National Oceanographic Institute. Prince Albert of Monaco officially opened it in 1906.

In this lab, Bruce kept his weather and ocean tools for future trips. He also met other explorers there, like Nansen and Shackleton. His main job was to manage the science reports from the Scottish Antarctic Expedition. These reports were published between 1907 and 1920. One volume, Bruce's own log, was not published until 1992. Bruce wrote many letters to other experts. He dedicated his book Polar Exploration to Sir Joseph Hooker, who had explored Antarctica earlier.

In 1914, talks began about finding a permanent home for Bruce's collection. They also wanted a home for the specimens from the Challenger expedition. Bruce suggested a new center to honor Sir John Murray, who had died that year. Everyone agreed, but World War I stopped the project. The Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory stayed open until 1919. Bruce was in poor health and had to close it. He sent his collections to the Royal Scottish Museum, the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS), and the University of Edinburgh.

More Antarctic Plans

On March 17, 1910, Bruce presented new plans to the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS). He wanted to lead another Scottish Antarctic expedition. His plan was for one group to stay near Coats Land. Another group would go to the Ross Sea on the other side of Antarctica. In the second year, the Coats Land group would walk across the continent, going through the South Pole. The Ross Sea group would meet them. The expedition would also do a lot of science work. Bruce thought it would cost about £50,000.

The RSGS and other Scottish groups supported his plans. But the timing was bad. The Royal Geographical Society in London was busy with Robert Scott's Terra Nova Expedition. They were not interested in Bruce's plans. No rich people offered money. Bruce tried hard to get money from the government, but he failed. Bruce thought Markham was still working against him.

Finally, Bruce accepted his trip would not happen. He then gave help and advice to Ernest Shackleton. In 1913, Shackleton announced plans similar to Bruce's. Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition received a lot of money.

Scottish Spitsbergen Syndicate

During his trips to Spitsbergen in 1898 and 1899, Bruce found coal, gypsum, and possibly oil. In 1906 and 1907, he went back with Prince Albert. Their main goal was to map Prince Charles Foreland. Bruce found more coal and signs of iron there. Based on these findings, Bruce started a company in July 1909. It was called the Scottish Spitsbergen Syndicate.

At that time, Spitsbergen was considered unclaimed land. People could claim mining rights by just registering them. Bruce's company claimed land on Prince Charles Foreland and other islands. They raised money for a detailed exploration trip in 1909. The results were "disappointing," and the trip used almost all the company's money.

Bruce visited Spitsbergen two more times, in 1912 and 1914. But World War I stopped further work. In 1919, a new, bigger company took over. Bruce hoped to find oil, but science trips in 1919 and 1920 did not find any. They did find new coal and iron ore. After this, Bruce was too sick to continue his involvement. The company spent most of its money on these trips. It continued until 1952 but never made a profit. Another company eventually bought its claims.

Later Life and Legacy

Polar Medals Not Given

Bruce received many awards during his life. He got gold medals from different geographical societies. He also received an honorary degree from the University of Aberdeen. But he never received the Polar Medal. This medal is given by the King or Queen, based on advice from the Royal Geographical Society. Members of almost every other British Antarctic expedition received this medal, but not the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition.

Bruce and his friends believed Markham was to blame for this. They tried many times to get the medal awarded. Robert Rudmose Brown, who wrote about the Scotia trip, said this was an insult to Scotland. Bruce wrote to his Member of Parliament in 1915. He described Markham's unfairness. He said his brave team members were dying without the medal. But nothing changed.

Almost a century later, in 2002, the issue was raised in the Scottish Parliament. A politician suggested that Bruce should be given the Polar Medal after his death. This was to recognize his important role in polar science.

Final Years

When World War I started in 1914, Bruce's business plans were on hold. He offered to help the Admiralty, but he did not get a job. In 1915, he worked for a whaling company in the Seychelles for four months, but it failed. When he came back to Britain, he finally got a small job at the Admiralty.

Bruce kept trying to get recognition for his work. He pointed out how differently the Scottish expedition was treated compared to English ones. After the war, he tried to restart his projects. But his health was getting worse. He had to close his laboratory. In 1920, he went to Spitsbergen in an advisory role. He was too ill to do much work. He was later in hospitals in Edinburgh. He died on October 28, 1921. As he wished, he was cremated. His ashes were taken to South Georgia and scattered in the southern sea. Even though he often had little money, his estate was worth £7,000 when he died.

How Bruce is Remembered

After Bruce died, his friend Robert Rudmose Brown wrote that Bruce's name would always be remembered among great explorers. Rudmose Brown's book about Bruce was published in 1923. That same year, a prize was created in Edinburgh for young polar scientists. It was called the Bruce Memorial Prize. After this, Bruce was respected by scientists, but the public mostly forgot him. When he was mentioned in books about other explorers, it was often not very accurate.

In the early 2000s, people started to look at Bruce's work again. This was partly because of the 100-year anniversary of the Scottish expedition. Scotland also had a stronger sense of its own identity. In 2003, a modern research ship named "Scotia" used Bruce's old information. They studied climate change in South Georgia. This trip found important things about global warming. They saw their work as a way to honor "Britain's forgotten polar hero, William Speirs Bruce."

A BBC TV show about Bruce in 2011 showed his careful science. It compared it to other explorers who wanted to gain fame for their country. A new writer, Peter Speak (2003), said the Scottish expedition was "the most cost-effective and carefully planned scientific expedition" of its time.

Speak also thought about why Bruce did not get more success after his big trip. He suggested it was because Bruce was shy and not good at public relations. He was also very proud of being Scottish. He did not promote his work like Scott and Shackleton did. A friend said he was "as prickly as the Scottish thistle itself." Sometimes he was not tactful.

Bruce wanted Scotland to be equal with other nations. His national pride was very strong. He wrote that "Science" was the goal of his expedition, but "Scotland" was on its flag. This focus on Scotland could bother some people. But those who worked with him respected him. John Arthur Thomson, who knew Bruce well, wrote that Bruce never complained about himself. But he would fight fiercely if he thought his men, his lab, or his Scotland were treated unfairly.

See also

In Spanish: William Speirs Bruce para niños

In Spanish: William Speirs Bruce para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |