Scottish National Antarctic Expedition facts for kids

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE), from 1902 to 1904, was a big adventure led by William Speirs Bruce. He was a scientist from the University of Edinburgh. Even though another famous explorer, Robert Falcon Scott, was on his own expedition at the same time, the SNAE did a lot of important scientific work.

The expedition achieved many things. They set up the first weather station in Antarctica, which was staffed by people. They also discovered new land east of the Weddell Sea. They collected many animal and geological samples. These discoveries helped start the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory in 1906.

Bruce was very experienced in polar regions, having traveled to the Antarctic and Arctic in the 1890s. He wanted to join Scott's expedition but also suggested using a second ship to explore the Weddell Sea. This idea was not liked by Sir Clements Markham, who was in charge of the Royal Geographical Society. So, Bruce found his own money and support from the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

Many people have said this expedition was "the most cost-effective and carefully planned scientific expedition" of its time. However, Bruce and his team did not get any special awards or recognition from the British Government, like the Polar Medal. After this expedition, Bruce didn't go back to Antarctica, but he kept exploring the Arctic. His focus on pure science was not as popular as the adventures of explorers like Scott, Shackleton, and Amundsen. Because of this, his achievements were often forgotten. But the weather station they built, called "Omond House" on Laurie Island in 1903, is still working today as the Orcadas Base.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Adventure

William Speirs Bruce spent many years learning about natural sciences and oceanography in the 1880s and 1890s. He even volunteered to help a famous oceanographer, Dr John Murray, sort out specimens from the Challenger expedition. In 1892, Bruce went on a trip to the Antarctic on a whaler ship called Balaena. He loved it so much that he wanted to lead his own expedition, but he couldn't find money for it.

Later, he worked at a weather station and joined other trips to the Arctic. He even became friends with Prince Albert of Monaco, who was also a famous oceanographer.

In 1899, Bruce wanted to join a big Antarctic expedition that the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) was planning. He was very qualified. But he also suggested using a second ship, funded by Scotland, to explore a different part of Antarctica. The RGS president, Sir Clements Markham, called this idea "mischievous." After some arguments, Bruce decided to go on his own. This is how the idea for a Scottish expedition began. A rich family, the Coats family, gave a lot of money to support Bruce's Scottish expedition. But this also made Sir Clements Markham dislike Bruce.

The Ship: Scotia

In 1901, Bruce bought a Norwegian whaling ship for £2,620. Over the next few months, this ship was completely rebuilt to become an Antarctic research vessel. It got two laboratories, a darkroom, and lots of special equipment. They added huge spinning machines to the deck to pull up marine samples from deep in the sea. Other tools were put in place to measure sea depth, collect water and seabed samples, and observe weather and magnetism.

The ship's body was made stronger to handle the thick Antarctic ice. It was also changed into a barque (a type of sailing ship) with extra engines. All this work made the ship cost £16,700. The Coats family paid for most of this, giving £30,000 out of the total expedition cost of £36,000. The ship was renamed Scotia and was ready for testing in August 1902.

The Team

The expedition had six scientists, including Bruce himself. David Wilton was the zoologist; he had lived in Russia and knew how to ski and use dog sleds. Robert Rudmose-Brown was the botanist, studying plants. Dr James Harvie Pirie was the geologist, bacteriologist, and doctor for the expedition. Robert Mossman was in charge of weather and magnetic studies. Alastair Ross, a medical student, prepared animal specimens.

Bruce chose Thomas Robertson to be Scotia's captain. Robertson was an experienced sailor in icy waters. The rest of the 25 officers and crew were all Scotsmen, many of whom had worked on whaling ships in cold seas. They signed up for three years.

What They Wanted to Do

The goals of the expedition were published in magazines in October 1902. They wanted to set up a winter station "as close to the South Pole as possible." They also planned to do deep-sea research in the Antarctic Ocean and study weather, geology, biology, and the land.

The expedition was very Scottish. A newspaper called The Scotsman wrote that "The leader and all the scientific and nautical members of the expedition are Scots; the funds have been collected for the most part on this side of the Border." This meant it was a Scottish effort, unlike other expeditions that got government help.

Since most of the work would be at sea or at the winter station, they only took a few dogs for short sledging trips. The dogs were good at pulling, but their paws sometimes got cut on rough ice.

The Journey Begins

First Trip, 1902–1903

Scotia left Troon, Scotland, on November 2, 1902. On its way south, it stopped at ports in Ireland, Madeira, and the Cape Verde Isles. They tried to land at a tiny group of rocks called St Paul's Rocks, but it was dangerous. The expedition's doctor, James Harvie Pirie, almost got eaten by sharks! Scotia reached Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands on January 6, 1903, to get more supplies.

On January 26, Scotia sailed into Antarctic waters. They had to navigate through heavy pack ice near the South Orkney Islands. On February 4, they landed on Saddle Island, South Orkney Islands, and collected many plant and rock samples. The ship then continued south into the Weddell Sea, reaching 70°25′S. But new ice started to form, so Captain Robertson had to turn the ship north.

Since they hadn't found land to winter on, they needed to decide quickly where to stay. Bruce chose to go back to the South Orkneys. Even though it was far from the South Pole, it was a good spot for a weather station because it was closer to South America.

It took a month to reach the islands. After several tries and with the ship's rudder damaged by ice, Scotia finally found a safe bay on Laurie Island. On March 25, the ship anchored in the ice. They quickly turned it into a winter home. Bruce started a full program of work, including weather readings, collecting sea samples, and gathering plants and rocks.

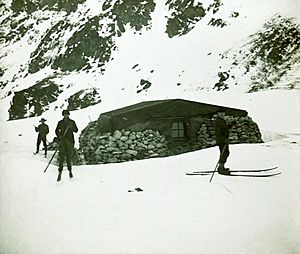

Their biggest task was building a house for the people who would stay on Laurie Island to run the weather station. The building was 20 by 20 feet, made from local stones, with a roof of wood and canvas. It had two windows and could fit six people. They named it "Omond House" after Robert Omond, a supporter of the expedition. One of the team members wrote that it was a "wonderfully fine house and very lasting."

Everyone stayed healthy except for the ship's engineer, Allan Ramsay, who had a heart condition. He sadly died on August 6 and was buried on the island.

As winter ended, the team did more activities, including sledge trips to nearby islands. They built a wooden hut for magnetic observations and a tall stone pile with the Union Flag and the Scottish flag on top. Scotia was ready to sail again, but it was stuck in ice until November 23. Four days later, it left for Port Stanley, leaving six people at Omond House to run the weather station.

Buenos Aires, 1903–1904

On December 2, 1903, the expedition reached Port Stanley. They finally got news from the outside world. After a week's rest, Scotia sailed to Buenos Aires for repairs and supplies. Bruce also wanted to convince the Argentine government to take over the Laurie Island weather station after the expedition left. On the way, Scotia got stuck in the Río de la Plata river for several days before a tugboat helped it into port on December 24.

For the next four weeks, while the ship was being fixed, Bruce talked with the Argentine government about the weather station. On January 20, 1904, they made an agreement. Three Argentine scientists would go back to Laurie Island to work with Robert Mossman for a year. Bruce officially gave Omond House, its furniture, supplies, and all the weather instruments to the Argentine government. The station, renamed Orcadas Base, has been working ever since.

Some of the original crew left in Buenos Aires, and new people were hired. Scotia left for Laurie Island on January 21, arriving on February 14. A week later, after settling the weather team, Scotia set off for its second trip into the Weddell Sea.

Second Trip, 1904

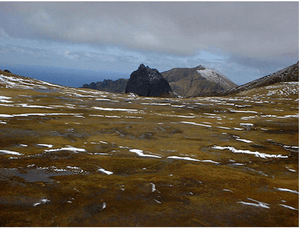

Scotia sailed south-east into the Weddell Sea. They didn't see any heavy ice until March 3, when they were stopped at 72°18'S, 17°59'W. They measured the sea depth, and it was much shallower than expected, suggesting land was nearby. A few hours later, they reached an ice barrier that blocked their way. They followed this barrier south for about 150 miles. Another depth measurement close to the barrier showed it was very shallow, meaning there was land behind it. Soon, they could faintly see the land, and Bruce named it Coats Land after his main supporters. This was the first time anyone had seen the eastern edge of the Weddell Sea so far south.

On March 9, 1904, Scotia reached its furthest south point at 74°01'S. The ship got stuck in the ice, and it looked like they might be trapped for the winter. During this time, the ship's bagpiper, Gilbert Kerr, was famously photographed playing for a penguin! On March 13, the ship broke free and slowly moved north-east. Throughout this journey, they continued to measure depths and collect samples, learning a lot about the ocean and sea life in the Weddell Sea.

Scotia then headed for Cape Town, stopping at Gough Island, a remote volcanic island that no scientists had ever visited. On April 21, Bruce and five others spent a day collecting specimens there. The ship arrived in Cape Town on May 6. After more research, Scotia sailed for home on May 21.

On the way home, they visited Saint Helena and saw Napoleon's old house. They also stopped at Ascension Island and were amazed by giant turtles. Their last stop was in the Azores before heading back to Scotland.

Back Home

The expedition received a warm welcome when it returned to the Clyde in Scotland on July 21, 1904. A big party was held, and King Edward VII sent a congratulatory message. Bruce received a gold medal from the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, and Captain Robertson received a silver medal.

After the expedition, scientists cataloged over 1,100 species of animals, with 212 of them being new to science! However, the British government in London did not officially recognize their work. Members of the SNAE were not given the special RGS Polar Medals, which were given to Scott's expedition members. Bruce fought for years to get this recognition, feeling it was unfair to his country and his expedition. Some people think this was because Bruce was very proud of being Scottish and showed it openly.

A very important result of the expedition was Bruce setting up the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory in Edinburgh. Prince Albert of Monaco officially opened it in 1906. This lab stored all the amazing biological, animal, and rock samples collected during the Scotia voyages and Bruce's earlier trips. It was also where the scientific reports from the SNAE were prepared. Famous polar explorers like Nansen, Amundsen, and Shackleton even visited the lab.

Bruce continued to visit the Arctic for science and business, but he never led another Antarctic expedition. His plans for a trip across Antarctica didn't happen because he couldn't get enough money. The SNAE scientific reports took many years to finish, with most published between 1907 and 1920. Bruce had to close his laboratory in 1919 because of money problems. He died two years later, at 54.

By then, the Scotia expedition was almost forgotten, even in Scotland. It was overshadowed by the more exciting adventures of Scott and Shackleton. Bruce was not very good at public relations and sometimes made powerful enemies. But Professor Tony Rice, an oceanographer, said that Bruce's expedition did "a more comprehensive programme than that of any previous or contemporary Antarctic expedition."

The expedition ship Scotia was used as a cargo ship during World War I. On January 18, 1916, it caught fire and was destroyed in the Bristol Channel. One hundred years after Bruce, in 2003, a new expedition used the information collected by the SNAE to study climate change in South Georgia. This modern expedition said that their work on global warming would be a great tribute to the SNAE's amazing early research.

See also

- Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

- List of Antarctic expeditions

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |