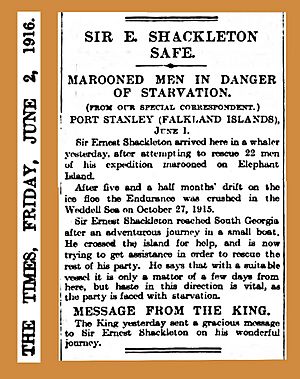

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition facts for kids

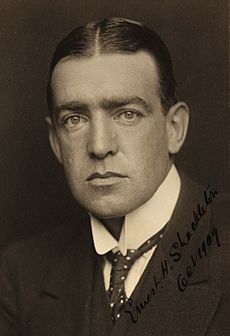

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 was one of the last big adventures from the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. It was planned by Sir Ernest Shackleton. His goal was to be the first to cross the entire Antarctic continent by land. After Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole in 1911, Shackleton felt this crossing was the "one great main object of Antarctic journeyings." Even though Shackleton's expedition didn't achieve this goal, it became famous as an incredible story of survival and bravery.

Shackleton had explored Antarctica before on the Discovery expedition (1901–1904) and led the Nimrod expedition (1907–1909). For this new adventure, he planned to sail to the Weddell Sea. A group would land near Vahsel Bay and then march across the continent, passing the South Pole, to the Ross Sea. Another team, called the Ross Sea party, would set up camp in McMurdo Sound. From there, they would leave supplies along the route to help the crossing party. These supplies were super important because the main group couldn't carry enough food for the whole trip. The expedition needed two ships: Endurance for Shackleton's Weddell Sea team, and Aurora for the Ross Sea party, led by Aeneas Mackintosh.

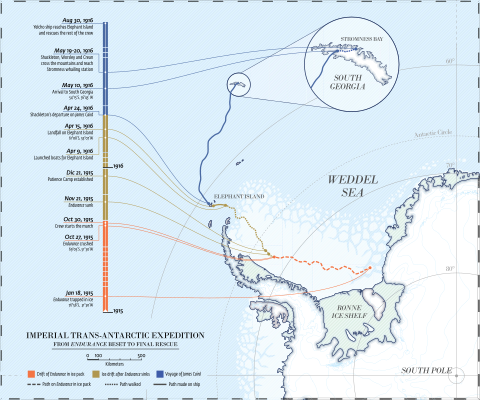

Sadly, the Endurance got stuck in the ice of the Weddell Sea before it could reach Vahsel Bay. It drifted north, trapped in the thick ice, all through the Antarctic winter of 1915. Eventually, the ice crushed the ship, and it sank. This left 28 men stranded on the ice. After months living in temporary camps as the ice kept drifting north, the group used lifeboats saved from the ship. They managed to reach the harsh, empty Elephant Island. Shackleton and five others then made an amazing 800-mile (1,300 km) journey in an open boat called the James Caird. They reached South Georgia. From there, Shackleton finally arranged a rescue for the men left on Elephant Island. Everyone made it home safely. The incredibly well-preserved wreck of Endurance was found on the seafloor in 2022.

On the other side of Antarctica, the Ross Sea party faced huge challenges to complete their mission. The Aurora was blown away from its anchors during a storm and couldn't return. This left the shore party stranded without proper supplies. Even though they still managed to lay the supply depots, three people died before the party was finally rescued.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Adventure

How the Expedition Began

After his previous trip, the Nimrod Expedition, Ernest Shackleton was famous. But he still felt restless. By 1912, his future plans for Antarctica depended on what happened with other expeditions. These included Robert Falcon Scott's Terra Nova'' Expedition and the Norwegian team led by Roald Amundsen.

When Shackleton heard that Amundsen had reached the South Pole in March 1912, he said: "The discovery of the South Pole will not be the end of Antarctic exploration." He believed the next big goal was "a transcontinental journey from sea to sea, crossing the pole." He knew other explorers were also thinking about this.

A German expedition led by Wilhelm Filchner had tried to explore the Weddell Sea in 1911. Filchner didn't manage to set up a base, but his reports about possible landing spots in Vahsel Bay were useful to Shackleton.

In February 1913, news reached London that Scott and his team had died returning from the South Pole. Despite this sad news, Shackleton started preparing his own journey. He asked for money and help from many people. Some, like former Prime Minister Lord Rosebery, weren't interested. But others, like William Speirs Bruce, who had his own plans for a crossing, generously shared his ideas with Shackleton.

On December 29, 1913, Shackleton got his first big financial help: £10,000 from the British government. He then announced his plans to the public.

Shackleton's Big Plan

Shackleton named his new adventure the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. He wanted people from all over the British Empire to support it. In early 1914, he shared a detailed plan. The expedition would have two groups and two ships.

The Weddell Sea party would sail on the Endurance to the Vahsel Bay area. Fourteen men would land there. Six of them, led by Shackleton, would form the transcontinental party. This group would have 69 dogs and two motor sledges. They would travel 1,800-mile (2,900 km) to the Ross Sea. The other eight men would do scientific work.

The Ross Sea party would set up their base in McMurdo Sound, on the other side of the continent. Their job was to lay out supply depots along the route for Shackleton's team. They hoped to meet the transcontinental party near the Beardmore Glacier and help them finish the journey. They would also do scientific observations.

Finding the Money

Shackleton thought he would need about £50,000 to make his plan happen. He preferred to ask wealthy people for money rather than the general public. At first, it was hard to get funding.

The first big help came in December 1913, when the British government offered £10,000. This was on the condition that Shackleton found the same amount from private donors. The Royal Geographical Society gave him £1,000.

In February 1914, The New York Times reported that writer J. M. Barrie secretly gave $50,000 (about £10,000). As time ran out, more money came in during the first half of 1914. Dudley Docker gave £10,000. A rich tobacco heiress, Janet Stancomb-Wills, gave a "generous" amount. In June, Scottish businessman Sir James Key Caird donated £24,000. Shackleton told the Morning Post that this "magnificent gift relieves me of all anxiety."

With enough money, Shackleton bought a 300-ton ship called Polaris for £14,000. He renamed her Endurance, after his family motto: "By endurance we conquer." He also bought Douglas Mawson's ship, Aurora, for £3,200. This ship would be used by the Ross Sea party.

The total cost of the expedition was around £80,000. Shackleton also sold the newspaper rights to the Daily Chronicle and created a film company to make money from the expedition's footage.

The Expedition Team

It's a famous story that Shackleton put an ad in a London paper saying: "Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in event of success." However, no one has ever found this ad, so it's probably just a legend.

Shackleton received over 5,000 applications! This included a letter from "three sporty girls" who offered to wear men's clothes if needed.

Eventually, the crews for both parts of the expedition were chosen, with 28 men for each. Some joined at the last minute. For example, William Lincoln Bakewell joined in Buenos Aires. His friend Perce Blackborow even stowed away when his application was turned down!

Shackleton chose Frank Wild as his second-in-command. Wild had been with Shackleton on two earlier expeditions. For the captain of the Endurance, Shackleton picked Frank Worsley. Tom Crean, a hero from another Antarctic trip, became the Endurance's second officer.

The scientific team on Endurance included two doctors, a geologist, a biologist, a physicist, and a weather expert. Frank Hurley was the photographer, and George Marston was the artist.

The Ross Sea party's team was put together quickly. Only their commander, Mackintosh, and Ernest Joyce had been to Antarctica before.

The Weddell Sea Journey

Trapped in the Ice

The Endurance left Plymouth, England, on August 8, 1914. Shackleton wasn't on board yet because he had other expedition business. He joined the ship later in Buenos Aires. The ship then sailed for South Georgia, arriving on November 5. Shackleton had hoped to cross Antarctica in the first season (1914–1915), but he soon realized this wasn't possible. He forgot to tell the Ross Sea party about this change.

On December 5, the Endurance left South Georgia for Antarctica. Just two days later, Shackleton was surprised to find thick pack ice much further north than expected. The ship had to carefully navigate through it. On December 14, the ice was so thick it stopped the ship for a whole day. Shackleton wrote that he was ready for bad conditions in the Weddell Sea, but he hoped the ice would be loose. Instead, it was "very obstinate."

The Endurance moved very slowly. On January 15, 1915, they saw a huge glacier that looked like a good landing spot. But Shackleton thought it was too far north of Vahsel Bay, so they didn't stop. He later regretted this choice. On January 17, the ship reached 76° 27′S, where they could faintly see land. Shackleton named it Caird Coast.

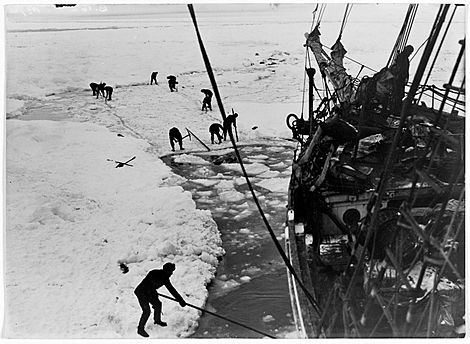

The Endurance was now close to Luitpold Land, where Vahsel Bay was. But the next day, the ship was forced northwest by the ice. It then got completely stuck at 76° 34′S, 31° 30′W. After ten days of being stuck, they turned off the ship's engines to save fuel. The crew tried hard to free the ship with tools, but it was no use. Shackleton started to think they might have to spend the winter trapped in the ice.

Drifting with the Ice

On February 22, 1915, the Endurance reached its furthest south point while still trapped: 76° 58′S. After that, it began drifting north with the ice. On February 24, Shackleton realized they would be stuck all winter. He ordered the dogs off the ship into special ice-kennels. The ship's inside was made into living quarters for the men. They even set up a radio, but they were too far away to send or receive signals.

Shackleton knew about another ship, the Deutschland, which had been trapped in the same area three years earlier. That ship broke free after six months. Shackleton hoped the Endurance would do the same and allow them to try for Vahsel Bay next spring.

In February and March, the ship drifted very slowly. But as winter arrived, the speed picked up, and the ice around them changed. On April 14, Shackleton wrote that the ice was "piling and rafting." If the ship got caught in this, it would be "crushed like an eggshell." By May, the ship was still drifting north. It would be at least four months until spring, and there was no guarantee the Endurance would break free. Shackleton started thinking about finding another landing spot if they could reach the western side of the Weddell Sea. "In the meantime," he wrote, "we must wait."

During the dark winter months, Shackleton focused on keeping his men fit and their spirits high. They exercised the dogs, took walks in the moonlight, and even put on plays. Special days like Empire Day were celebrated. The ice started to break up on July 22. On August 1, a strong storm caused the ice floe around the ship to break apart. The pressure pushed huge ice masses under the ship, making it tilt badly. Shackleton wrote that the pressure was "awe-inspiring." This danger passed, and the next few weeks were calm.

On September 30, the ship got its "worst squeeze" yet. The pressure was so strong that on October 24, the ship's side was forced against a large ice floe. The hull began to bend and splinter, and water poured into the ship. The sounds were like "heavy fireworks and the blasting of guns." Supplies and three lifeboats were moved onto the ice. The crew tried to fix the ship and pump out the water. But on October 27, 1915, in freezing temperatures, Shackleton ordered everyone to abandon ship. The ship was at 69° 05′S, 51° 30′W. The wreckage stayed afloat for a few weeks, allowing the crew to save more supplies, including Frank Hurley's photos and cameras. Hurley chose the best 120 photos and destroyed the rest to save weight. On November 21, the ship finally sank beneath the ice. The Endurance wreck was found on March 5, 2022, almost 107 years later.

Living on the Ice

With the Endurance gone, the plan to cross Antarctica was over. Now, the goal was simply to survive. Shackleton wanted to march the crew west to a safe place. His first idea was Paulet Island, where he knew there was a hut with food. Other options were Snow Hill Island or Robertson Island. Shackleton thought they could reach one of these islands, then cross Graham Land to get to whaling stations. He calculated they were 346 miles (557 km) from Paulet Island. Worsley thought the march was too risky and they should wait for the ice to carry them to open water. Shackleton disagreed.

Before they started marching, Shackleton ordered the weakest dogs to be shot to save food. This included the carpenter Harry McNish's cat, Mrs Chippy. The group set out on October 30, 1915, pulling two lifeboats on sledges. But the sea ice was terrible, full of bumps and ridges. In three days, they only moved two miles (3.2 km). On November 1, Shackleton stopped the march. They would make camp and wait for the ice to break up. They called their camp "Ocean Camp." Parties kept visiting the Endurance wreck, which was still drifting nearby, to get more supplies.

The ice wasn't drifting very fast, but by late November, it was moving seven miles (11 km) a day. By December 5, they had passed 68°S, but the direction was turning slightly east. This made it harder to reach Snow Hill Island. Paulet Island was still a possibility, about 250 miles (400 km) away. Shackleton wanted to shorten the lifeboat journey. So, on December 21, he announced a second march.

However, conditions hadn't improved. Temperatures were warmer, and the men sank to their knees in soft snow while pulling the heavy boats. On December 27, McNish refused to work, arguing that they were no longer under naval law. Shackleton firmly handled the situation, and McNish obeyed. Two days later, after only seven and a half miles (12.1 km) of progress in seven days, Shackleton stopped the march. He said, "It would take us over three hundred days to reach the land." The crew set up their tents and called their new home "Patience Camp." They would stay there for over three months.

Supplies were running low. Hurley and Macklin went back to Ocean Camp to get food they had left behind. Food shortages became serious, and seal meat became their main food. In January, most of the remaining dogs were shot because they ate too much seal meat. The last two dog teams were shot on April 2, and their meat was added to the rations.

The ice drift became unpredictable. By March 17, Patience Camp was at the same latitude as Paulet Island, but 60 nanometres (6.0×10−11 km) to its east. Shackleton said it might as well have been 600 miles away.

The party could now see land in the distance. They were too far north for Snow Hill or Paulet Island. Shackleton's hopes were now on two small islands at the northern tip of Graham Land: Clarence Island and Elephant Island, about 100 nautical miles (190 km) north of their position. He then thought Deception Island might be a better target. It was further west but sometimes visited by whalers, so it might have supplies. Clarence and Elephant Islands were empty. Reaching any of these places would mean a dangerous journey in the lifeboats once the ice floe broke up. The lifeboats were named after the expedition's main sponsors: James Caird, Dudley Docker, and Stancomb Wills.

The Lifeboat Journey to Elephant Island

The end of Patience Camp came on April 8, when the ice floe suddenly split. The camp was now on a small, triangular piece of ice. If it broke up, it would be a disaster. Shackleton got the lifeboats ready. He decided they would try to reach Deception Island, hoping to find wood from a small church there to build a better boat.

At 1 p.m. on April 9, the Dudley Docker was launched, and an hour later, all three boats were on the water. Shackleton commanded the James Caird. Worsley was in charge of the Dudley Docker. Hubert Hudson was supposed to lead the Stancomb Wills, but because he was not well, Tom Crean was the real leader.

The boats were surrounded by ice. Progress was dangerous and slow. Often, the boats were tied to ice floes, or dragged onto them, while the men waited for conditions to improve. Shackleton kept changing his mind about their destination. On April 12, he decided against the islands and aimed for Hope Bay on Graham Land. But conditions in the boats were terrible. Temperatures were sometimes as low as −20 °F (−29 °C), food was scarce, and the men were constantly soaked in icy water. They were becoming exhausted. So, Shackleton decided that Elephant Island, the closest safe place, was their best option.

On April 14, the boats were off the southeast coast of Elephant Island, but they couldn't land because of the steep cliffs. The next day, the James Caird found a narrow shingle beach on the northern side. Soon after, all three boats, which had been separated, reunited there. This beach wasn't safe for a long-term camp. So, the next day, Wild and a crew explored the coast and found a better spot seven miles (11 km) to the west. The men quickly moved to this new location, which they called Cape Wild.

The James Caird Voyage

Elephant Island was far away, empty, and rarely visited by ships. To get help, they needed to adapt one of the lifeboats for an 800-mile (1,300 km) journey across the Southern Ocean to South Georgia. Shackleton decided against the less dangerous trip to Deception Island because many of his men were too weak. Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands was closer, but they couldn't sail there against the strong winds.

Shackleton chose the six men for the boat trip: himself, Worsley, Crean, McNish, and sailors John Vincent and Timothy McCarthy. McNish immediately started preparing the James Caird, using whatever tools and materials he could find. Wild was left in charge of the Elephant Island party. Shackleton took supplies for only four weeks, believing that if they hadn't reached land by then, the boat would be lost.

The 22.5-foot (6.9 m) James Caird was launched on April 24, 1916. The trip depended on Worsley's perfect navigation in terrible conditions. The wind was helpful, but the rough seas quickly soaked everything in icy water. Ice built up thickly on the boat, making it heavy. On May 5, a strong storm almost destroyed the boat. Shackleton said the waves were the biggest he had seen in 26 years at sea. On May 8, after a 14-day struggle, they saw South Georgia. Two days later, after fighting strong winds, the party finally landed at King Haakon Bay.

Crossing South Georgia

After landing at King Haakon Bay, the James Caird party rested. Shackleton then had to decide what to do next. The whaling stations on South Georgia were on the northern coast. To reach them, they could either sail around the island or cross its unexplored interior. The James Caird was damaged, and Vincent and McNish were too weak to sail again. So, crossing the island was the only real choice.

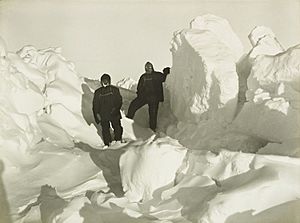

After five days, the party moved the boat a short distance to a deep bay. This would be their starting point for the crossing. Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean would make the land journey. The others would stay at "Peggotty Camp" and be picked up later. A storm on May 18 delayed their start. But at 2 a.m. the next morning, the weather was clear and calm. An hour later, the three men set out.

Their goal was the whaling station at Stromness, which was about 26 miles (40 km) away, across the Allardyce Range. They didn't have a map, so they had to guess their route. By dawn, they had climbed to 3,000 feet (910 m) and could see the northern coast. They realized they were above Possession Bay and needed to go east to reach Stromness. This meant several detours that made the journey longer. At the end of the first day, they slid down a mountainside on a makeshift rope sledge to get to the valley below. They traveled through the night by moonlight, climbing towards a gap in the next mountain ridge.

Early on May 20, they saw Husvik Harbour below them. They knew they were on the right track. At 7 a.m., they heard a steam whistle from Stromness. It was "the first sound created by an outside human agency that had come to our ears since we left Stromness Bay in December 1914." After a difficult descent, including going down a freezing waterfall, they finally reached safety. Shackleton later wrote that he felt "Providence guided us." He said it often felt like there were four people, not three, during their 36-hour march. Worsley and Crean also felt this "Third Man factor."

The Rescue

Shackleton's first job at Stromness was to arrange for his three companions at Peggotty Camp to be picked up. A whaling ship was sent, with Worsley guiding the way. By the evening of May 21, all six men from the James Caird party were safe.

It took four tries for Shackleton to return to Elephant Island to rescue the stranded party. He left South Georgia just three days after arriving, using a large whaling ship called The Southern Sky. But thick pack ice, about 70 miles (110 km) from Elephant Island, blocked their way. The ship wasn't built for breaking ice, so they had to go back to Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

In Port Stanley, Shackleton sent a message to London asking for a suitable rescue ship. He was told nothing would be available until October, which he felt was too late. With help from the British Minister in Montevideo, Shackleton got a tough trawler, Instituto de Pesca No. 1, from the Uruguayan government. It sailed south on June 10, but again, the ice stopped them.

Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean then went to Punta Arenas, Chile. There, they met Allan MacDonald, who owned the schooner Emma. MacDonald prepared his ship for another rescue attempt, which left on July 12. But the ice defeated them again. Shackleton later named a glacier after MacDonald.

By mid-August, it had been over three months since Shackleton left Elephant Island. Shackleton asked the Chilean Navy to lend him Yelcho, a small steam tug. They agreed. On August 25, the Yelcho, captained by Luis Pardo of the Chilean Navy, set out for Elephant Island. This time, luck was on their side. The seas were open, and the ship got close to the island in thick fog. At 11:40 a.m. on August 30, the fog lifted, the camp was spotted, and within an hour, all the Elephant Island party were safely on board, heading for Punta Arenas.

Life on Elephant Island

- The Elephant Island party. Photo by Hurley. Not shown: Blackborow.

- Back row: Greenstreet, McIlroy, Marston, Wordie, James, Holness, Hudson, Stephenson, McLeod, Clark, Orde-Lees, Kerr, Macklin

- Front row: Green, Wild, How, Cheetham, Hussey, Rickinson, Bakewell

After Shackleton left with the James Caird, Wild took charge of the Elephant Island party. Some men were not well, either physically or mentally. Lewis Rickinson had a suspected heart attack, and Perce Blackborow couldn't walk because of frostbite in his feet. Hubert Hudson was very sad.

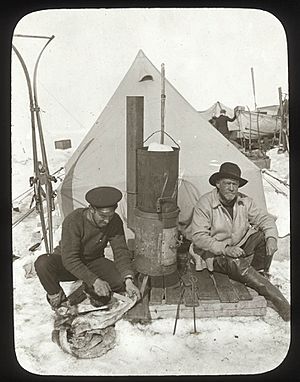

The most important thing for the party was to build a permanent shelter for the coming winter. Following an idea from Marston and Lionel Greenstreet, they made a hut, nicknamed the "Snuggery." They turned the two remaining lifeboats upside down and placed them on low stone walls. This gave them about five feet (1.5 m) of headroom. Using canvas and other materials, they made a simple but effective shelter.

Wild first thought they would only have to wait one month for rescue. He didn't want them to save up too much seal and penguin meat, as he thought that would be giving up hope. This caused some arguments with Orde-Lees, the storekeeper, who wasn't very popular.

As the weeks passed, much longer than Wild's first guess, he set up routines and activities to fight boredom. They kept a constant lookout for the rescue ship. They had cooking and cleaning duties, and went hunting for seals and penguins. They held concerts on Saturdays and celebrated special days. But as time went on with no sign of rescue, people started to feel sadder.

Blackborow's toes on his left foot got gangrene from frostbite. On June 15, the doctors, Macklin and McIlroy, had to amputate them in the candle-lit hut. They used the last of their chloroform. The whole operation took 55 minutes and was a success.

By August 23, it seemed Wild's plan of not saving food had failed. The sea was full of thick ice, which would stop any rescue ship. Food supplies were running out, and no penguins were coming ashore. Orde-Lees joked, "We shall have to eat the one who dies first." Wild was seriously thinking about taking a boat to Deception Island, hoping to find a whaling ship. He planned to leave on October 5. But then, on August 30, 1916, their ordeal suddenly ended when Shackleton and the Yelcho appeared.

The Ross Sea Party's Challenges

The Aurora left Hobart, Australia, on December 24, 1914. It was delayed by money and organization problems. They arrived in McMurdo Sound on January 15, 1915, later than planned. But the party's leader, Aeneas Mackintosh, immediately planned a trip to lay supplies on the Ross Ice Shelf. He thought Shackleton would try to cross Antarctica that first season.

The men and dogs were not used to the cold, and the team was very new to ice conditions. Their first trip on the ice was tough. They lost ten of their 18 dogs, and the men suffered from frostbite. They only managed to lay one incomplete supply depot.

On May 7, the Aurora, anchored at their headquarters at Cape Evans, was ripped from its moorings during a strong storm. It was carried far out to sea with drifting ice. It couldn't return to McMurdo Sound and stayed trapped in the ice for nine months. On February 12, 1916, after drifting about 1,600 miles (2,600 km), it reached open water and slowly made its way to New Zealand.

The Aurora had most of the shore party's fuel, food, clothes, and equipment. Only the special sledging rations for the depots had been unloaded. To continue their mission, the stranded shore party had to find supplies from old expeditions, like Scott's Terra Nova Expedition, which had been based at Cape Evans years earlier. They were able to start laying depots for the second season in September 1915.

In the following months, they laid the needed depots across the Ross Ice Shelf to the Beardmore Glacier. On the way back, the party got scurvy. Arnold Spencer-Smith, the expedition's chaplain and photographer, collapsed and died on the ice. The rest of the group reached the temporary shelter of Hut Point, a leftover from the Discovery Expedition. There, they slowly got better.

On May 8, 1916, Mackintosh and Victor Hayward decided to walk across the unstable sea ice to Cape Evans. They were caught in a blizzard and were never seen again. The survivors eventually reached Cape Evans. They then had to wait eight more months. Finally, on January 10, 1917, the repaired Aurora arrived to take them back to civilization. Shackleton was on the ship as an extra officer. He had been denied command by the governments that funded the rescue.

Coming Home and What Happened Next

The rescued party had not been in contact with civilization since 1914. They didn't know about the Great War happening. News of Shackleton's safe arrival in the Falklands briefly pushed war news off the front pages of British newspapers on June 2, 1916. The Yelcho received a hero's welcome in Punta Arenas. The rescued men were then taken to Valparaíso, Chile, where they also got a warm welcome before going home.

The expedition members returned home in small groups. It was a critical time in the war, so there were no big celebrations. When Shackleton finally arrived in England on May 29, 1917, after a short lecture tour in America, his return was barely noticed.

Despite McNish's hard work on the James Caird voyage, Shackleton recommended that he and three other men not receive the Polar Medal because of McNish's earlier disobedience. Most of the expedition members joined the military or navy. Before the war ended, two men—Tim McCarthy and Alfred Cheetham—were killed in action. Ernest Wild, Frank's younger brother from the Ross Sea party, died of typhoid. Many others were wounded or received awards for bravery.

After the war, Shackleton organized one last Antarctic expedition, the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition on Quest. It left London on September 17, 1921. Many of the Endurance crew joined him again.

Shackleton died of a heart attack on January 5, 1922, while the Quest was anchored at South Georgia. After his death, the expedition's plans were changed. Wild led a short trip that brought them close to Elephant Island. They could see the old landmarks, but the sea conditions made it impossible to land.

It would be over forty years before the first crossing of Antarctica was achieved. This was done by the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition from 1955–1958. This expedition started from Vahsel Bay, the same bay Shackleton had aimed for. They completed the entire journey in 98 days.

For Chile, the rescue of Shackleton's men marked the beginning of the country's official operations in Antarctica.

Images for kids

-

Corporate sponsorship for the expedition; Aurora is loaded with paraffin provided by Shell

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |