Shackleton–Rowett Expedition facts for kids

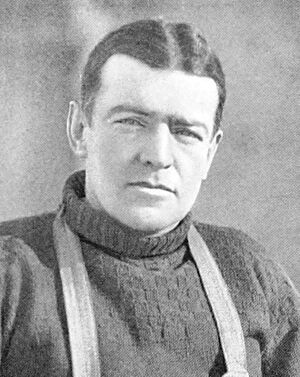

The Shackleton–Rowett Expedition (1921–22) was the last big adventure for Sir Ernest Shackleton. It was also the very end of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, a time when brave explorers pushed into the icy lands of the South Pole.

This trip was paid for by John Quiller Rowett. Because of its ship, the Quest, it's often called the Quest Expedition. The Quest was a small ship, once used for seal hunting. Shackleton first wanted to explore the Arctic and the Beaufort Sea. But the Canadian government didn't give him money, so he changed his plans and headed for the Antarctic instead. The Quest was too small and had many engine problems. It was not ready for such a tough journey. Sadly, before the expedition could really begin, Shackleton died on board the ship. This happened right after they arrived at South Georgia.

After Shackleton's death, Frank Wild, his second-in-command, took over. The expedition continued with a three-month trip to the eastern Antarctic. The Quest still had problems: it was slow, used a lot of fuel, rolled a lot in big waves, and leaked. The ship couldn't go as far east as they hoped. Its engine wasn't strong enough to break through the thick pack ice. After trying many times, Wild turned the ship back to South Georgia. On the way, they visited Elephant Island. This was where Wild and 21 other men had been stuck after their ship, the Endurance, sank six years earlier. That happened during Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

Wild thought about trying for a second, better season in the ice. He took the ship to Cape Town for repairs. But in June 1922, he got a message from Rowett. Rowett told him to bring the ship back to England. So, the expedition quietly ended. The Quest voyage is not well-known in history books. This is because Shackleton's death overshadowed everything else that happened.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Antarctic

What Was the Plan?

Even before his problems with the Canadian government, Shackleton thought about going south. He talked about exploring the South Atlantic and South Pacific islands. By June 1921, this plan grew. It included sailing all around the Antarctic continent. They also wanted to map about 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of unknown coastline.

The team also hoped to find "lost" islands. These included Dougherty Island, Tuanaki, and the Nimrod Islands. They would also look for valuable minerals on these lands. A science program was planned too. It included visiting Gough Island. They also wanted to study if there was a land connection under the ocean between Africa and America.

This expedition was a mix of old and new ways of exploring. Shackleton called it "pioneering." This was because they brought an airplane, though it was never used. Many new gadgets were on board. The ship's crow's nest (a lookout spot) was heated. Lookouts had heated clothes. There was a wireless radio and a device to automatically map the ship's path. Photography was very important, so they had many cameras. They also had a special machine to measure the deep sea.

All this equipment was possible because of John Quiller Rowett. He paid for most of the expedition. The exact amount is not known. But thanks to Rowett, the expedition came home without any debt. This was rare for Antarctic trips back then. Rowett was a businessman who also helped fund science research. He did this for science and because he was Shackleton's friend. His only reward was having his name in the expedition's title.

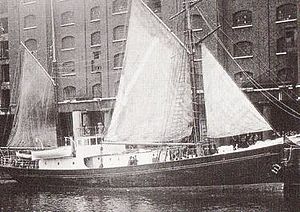

About the Ship: Quest

In March 1921, Shackleton named his ship Quest. It was a small ship, about 125 tons. It had sails and an engine. It was supposed to go eight knots (about 9 miles per hour). But it usually went only five and a half knots (about 6 miles per hour). The ship was not good in big waves. It was also not suited for long ocean trips. Shackleton himself said it wasn't ready for even a small storm.

One writer said that if the ship had gone to the Arctic, it would have been crushed by the ice. On its way south, the Quest often broke down. It needed repairs at almost every port.

Who Was on Board?

The Quest left London with 20 men. Eight of them had been with Shackleton on his Endurance expedition. One man, James Dell, had even been on Shackleton's Discovery trip 20 years before. Some of the old crew had not been fully paid from the Endurance trip. But they still joined Shackleton because they believed in him.

Frank Wild was the second-in-command, just like on the Endurance. This was his fourth trip with Shackleton. Frank Worsley, the Endurance's old captain, became the captain of the Quest. Other old friends included doctors Alexander Macklin and James McIlroy. There was also meteorologist Leonard Hussey, engineer Alexander Kerr, seaman Tom McLeod, and cook Charles Green. Shackleton thought Tom Crean would join. But Crean had retired to be with his family.

Some new people joined too. Roderick Carr was a pilot from New Zealand. He was supposed to fly the expedition's airplane. The plane was a special seaplane. But some parts were missing, so the plane was never used. Carr helped with science work instead. Other scientists included biologist Hubert Wilkins and geologist Vibert Douglas.

Two young Boy Scouts also joined, which got a lot of public attention. Norman Mooney and James Marr were chosen from about 1,700 Scouts. Mooney got very seasick and left the ship early. But Marr, an 18-year-old from Aberdeen, stayed for the whole trip. Shackleton and Wild praised him for his hard work and toughness.

The Expedition's Journey

Sailing South

The Quest sailed from St Katharine Docks, London, on September 17, 1921. King George V came to see them off. Huge crowds gathered to watch. James Marr wrote that it felt like "all London" was saying goodbye.

Shackleton first planned to sail to Cape Town. On the way, they would visit islands in the South Atlantic. From Cape Town, the Quest would go to Enderby Land in Antarctica. There, they would explore the coastline. After the summer, they would visit South Georgia. Then they would return to Cape Town for repairs.

But the ship's problems changed everything. Serious engine issues meant they had to stop for a week in Lisbon. They also stopped in Madeira and the Cape Verde Islands. These delays and the ship's slow speed made Shackleton change his mind. He decided to skip the island visits. Instead, he turned the ship towards Rio de Janeiro. There, the engine could get a full repair. The Quest reached Rio on November 22, 1921.

The engine repairs took four weeks in Rio. This meant they couldn't go to Cape Town and then to the ice. Shackleton decided to sail straight to Grytviken harbor in South Georgia. Equipment sent to Cape Town had to be left behind. Shackleton hoped they could find what they needed in South Georgia. He wasn't sure what they would do after South Georgia. Doctor Macklin wrote that Shackleton "does not know what he will do."

Shackleton's Death

On December 17, 1921, the day before the Quest was to leave Rio, Shackleton became ill. He might have had a heart attack. Doctor Macklin was called, but Shackleton refused to be checked. He said he was "better" the next morning. On the way to South Georgia, his shipmates noticed he was quiet and tired.

A big storm ruined their Christmas plans. Then, a new problem with the engine's furnace slowed them down. This caused Shackleton more stress. By January 1, 1922, the weather was calm. Shackleton wrote in his diary, "The year has begun kindly for us."

On January 4, they saw South Georgia. Later that morning, the Quest anchored at Grytviken. Shackleton visited the whaling station ashore. He seemed refreshed when he came back to the ship. He told Frank Wild they would celebrate Christmas the next day. He went to his cabin to write in his diary. "The old smell of dead whale permeates everything," he wrote. "It is a strange and curious place... A wonderful evening. In the darkening twilight I saw a lone star hover, gem like above the bay." He then went to sleep.

Shortly after 2:00 AM on January 5, Doctor Macklin was called to Shackleton's cabin. Shackleton complained of back pain and severe face pain. He asked for medicine. Shackleton died soon after. The cause was a very severe heart attack.

The death certificate said he died from heart problems. Later that morning, Wild, now in charge, told the shocked crew. He said the expedition would continue. Shackleton's body was taken ashore to be prepared for return to England. On January 19, Leonard Hussey took the body on a ship to Montevideo. But there, he found a message from Shackleton's wife, Emily. She asked for his body to be buried in South Georgia.

Hussey took the body back to Grytviken. Shackleton was buried on March 5 in the Norwegian cemetery. The Quest had already sailed. So, only Hussey was there from Shackleton's old friends. A simple cross marked the grave. Six years later, a tall granite column replaced it.

Journey to the Ice

As the new leader, Wild had to decide where the expedition would go. The ship's furnace problem was manageable. After getting more supplies, Wild decided to follow Shackleton's original plan. They would go east towards Bouvet Island. Then they would turn south to enter the ice near Enderby Land. There, they would start mapping the coast. They would also look for land that James Clark Ross had reported in 1842. How far they went depended on the weather, ice, and the ship.

The Quest left South Georgia on January 18. It headed southeast towards the South Sandwich Islands. The waves were huge. The ship was so full that water often washed over the sides. Wild wrote that the Quest rolled like a log, leaked, and used a lot of coal. It was also very slow. Because of this, he changed his plan at the end of January. They skipped Bouvet Island. Instead, they took a more southerly path. This brought them to the edge of the pack ice on February 4.

"Now the little Quest can really try her mettle," Wild wrote. The ship entered the loose ice. He noted that the Quest was the smallest ship to try to go through the heavy Antarctic ice. He wondered if they would escape or join other ships lost in the sea. As they went south, the ice got thicker. On February 12, they reached their furthest south point, 69°17'S. They were also at their furthest east, 17°9'E. This was still far from Enderby Land. Wild saw the ice and feared getting stuck. So, he turned the ship north and west.

He still hoped to break through the thick ice to the hidden land. On February 18, he turned the ship south again. But they had no more luck. On February 24, after many tries, Wild set a course west. They sailed across the mouth of the Weddell Sea towards Elephant Island. This was where Wild and 21 others had been stranded during Shackleton's expedition six years earlier. They would then return to South Georgia before winter.

The long trip across the Weddell Sea was mostly calm. But some crew members became restless. They were disappointed that the trip seemed to have no clear goal. Captain Worsley was especially critical of Wild's leadership. Wild wrote that he dealt with this by threatening "drastic treatment." On March 12, they reached 64°11'S, 46°4'W. This was where Ross had seen land in 1842. But there was no land, and the water was very deep. From March 15 to 21, the Quest was stuck in the ice. Running out of coal became a big worry. Wild hoped to get more fuel by using blubber from seals at Elephant Island.

On March 25, they saw Elephant Island. Wild wanted to visit Cape Wild, their old camp from the Endurance expedition. But bad weather stopped them. They looked at the site through binoculars. Then they landed on the western coast to hunt for elephant seals. They got enough blubber to mix with their coal. With a good wind, they reached South Georgia on April 6.

Coming Home

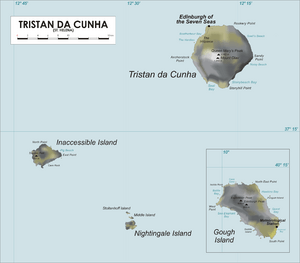

The Quest stayed in South Georgia for a month. During this time, Shackleton's old friends built a memorial to him. It was on a headland overlooking Grytviken harbor. On May 8, 1922, the Quest sailed for Cape Town. Wild hoped to get the ship repaired there for a better second season in the ice. Their first stop was Tristan da Cunha. This is a remote island west and south of Cape Town. After a rough trip through the "Roaring Forties" (windy seas), the Quest arrived on May 20. Following orders from Robert Baden-Powell, James Marr gave a flag to the local Scout Troop.

During their five-day stay, the expedition made short landings on Inaccessible Island and Nightingale Island. They collected plant and rock samples. Wild was not very impressed with Tristan da Cunha. He saw a lot of poverty. He said the people were "ignorant, shut off almost completely from the world."

After the Scout parade, the Quest sailed to Gough Island. This was 200 miles (320 km) to the east. There, they collected more samples. They arrived at Cape Town on June 18. Enthusiastic crowds greeted them. South African Prime Minister Jan Smuts held a reception. Local groups honored them with dinners.

They also met Rowett's agent. He had a message: they should return to England. Wild wrote that he would have liked "one more season in the Enderby Quadrant." He thought they could do a lot by starting from Cape Town. On July 19, they left Cape Town and sailed north. Their last stops were Saint Helena, Ascension Island, and São Vicente. On September 16, exactly one year after they left, they arrived at Plymouth harbor.

What Happened Next?

How Was the Expedition Seen?

Wild said the expedition ended quietly. But his biographer said there were excited crowds in Plymouth. Wild hoped the information they brought back would "prove of value."

The scientific results were summarized in five short parts of Wild's book. These showed the work of the scientists. They collected data and samples at every stop. Carr and Douglas also did geology work on South Georgia. A few science papers came from this. But it was "little enough to show for a year's work."

The expedition didn't have a clear goal. This was made worse by not stopping in Cape Town on the way south. Important equipment was missed. On South Georgia, Wild found little to make up for this. There were no dogs, so they couldn't use sleds. This stopped Wild's idea of exploring Graham Land.

Shackleton's death before the main work was a big blow. Some people wondered if Wild was a good enough replacement.

The airplane was a disappointment. Shackleton had hoped to be the first to use planes in Antarctica. But essential parts for the plane were sent to Cape Town and never picked up. The long-range radio didn't work well. The smaller radio only worked within 250 miles (400 km). Wild tried to install a new radio at Tristan da Cunha, but it also failed.

The End of an Era

After the Quest returned, there were no major expeditions to Antarctica for seven years. The expeditions that came after were different. They belonged to the "mechanical age," not the Heroic Age.

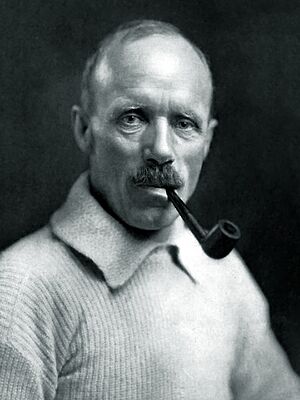

At the end of his story, Wild wrote about Antarctica: "I think that my work there is done." He never returned. His career, like Shackleton's, covered the whole Heroic Age. In 1923, he moved to South Africa. He had many business failures and health problems. He worked low-paying jobs.

In 1939, he was given a small yearly pension. Wild died on August 19, 1939, at age 66.

None of the other Endurance veterans went back to Antarctica. But Worsley did sail to the Arctic in 1925. Other Quest crew members continued exploring. Australian naturalist Hubert Wilkins became a pioneer pilot in the Arctic and Antarctic. He flew from Alaska to Spitsbergen in 1928. He also tried to fly to the South Pole in the 1930s. James Marr became a marine biologist. He joined several Australian expeditions in the late 1920s and 1930s. Roderick Carr became an Air Marshal in the Royal Air Force.

Images for kids

-

Dense pack ice in the Beaufort Sea

See also

In Spanish: Expedición Shackleton–Rowett para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |