Michael Doheny facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

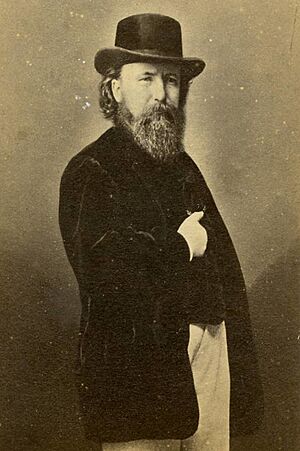

Michael Doheny

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 22 May 1805 Brookhill, near Fethard, County Tipperary |

| Died | 1 April 1862 (aged 56) New York City, United States |

| Allegiance | Young Ireland Irish Republican Brotherhood |

| Battles/wars | Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848 Fenian Rising |

Michael Doheny (born May 22, 1805 – died April 1, 1862) was an Irish writer and lawyer. He was a key member of the Young Ireland movement. He also helped start the Irish Republican Brotherhood. This was a secret Irish group. They aimed to make Ireland independent from Britain. They later launched important events like the Fenian Raids on Canada and the Easter Rising of 1916.

Contents

Michael Doheny's Early Life and Education

Michael Doheny was born in Brookhill, near Fethard, County Tipperary. He was the third son of a small farmer. He got a basic education from a traveling teacher. He worked on his family's farm while learning. As he grew up, he also taught local children. Michael wanted to become a lawyer. He hoped to help poor people in his community.

Both of Michael's parents died when he was a teenager. His oldest brother, also a teenager, became head of the family. Michael got sick with typhus at age 14 but recovered. When he was 20, his older brother died. Michael then took over the family farm. He decided to sell it to focus on his studies.

Michael studied law in London and Dublin. He became a lawyer in Ireland in 1838. He opened his law practice in Cashel, County Tipperary. He was chosen to be a legal advisor for Cashel. This allowed him to stop former town officials from misusing money and property. This made him well-known and respected.

Michael Doheny Enters Politics

In 1830, Michael Doheny helped with an election campaign in Tipperary. This led him to join Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association. This group wanted to cancel the Act of Union. This law had ended Ireland's own parliament. Michael officially joined the Repeal Association in 1841. He was soon part of their main committee. However, O'Connell found Michael hard to control. He also worried about Michael asking questions about the group's money.

By 1842, Michael was a successful lawyer in Cashel. That year, he married Mary Jane O'Dwyer. They moved into a new house with Mary Jane's mother. Michael and Mary Jane had four children: Morgan, Michael, Edmond, and Jane.

Also in 1842, Michael started working with more radical members of the repeal movement. One of these was Thomas Davis. Michael was different from many of Davis's friends. They were often from a higher social class. But many admired Michael's passion. One friend said he was "rough, generous, bold, a son of the soil." Michael helped start The Nation newspaper. This paper shared the ideas of the Young Irelanders. Michael was sometimes frustrated when his articles were not published. He also wrote a history of the American Revolution for the paper.

Historians believe Michael was a better speaker than a writer. He was very good at public meetings in Tipperary and Dublin. In 1843, he saw huge crowds at these "monster" meetings. He began to think these people could form a military force. Michael later claimed he and others planned these meetings to prepare Irish farmers for a war with Britain. However, historians now doubt this claim.

In 1845, the Repeal Association asked Michael for legal advice. They wanted to know if Irish Members of Parliament could legally leave the British Parliament. Michael reluctantly said that they could face legal trouble if they did. This was not what Daniel O'Connell wanted to hear. Their relationship became strained. Tensions grew when Michael disagreed with O'Connell about university education. Michael believed it should be open to all religions. Later in 1845, a political seat became open in Tipperary. Michael would have been a good choice. But O'Connell's party chose someone else.

In April 1846, William Smith O'Brien was jailed for a month. He refused to serve on a parliamentary committee. This caused a big split between the new Young Ireland movement and O'Connell's Repealers. Michael and the Young Irelanders supported O'Brien. They became more open about their radical ideas. The two groups officially split in July 1846. Michael was one of the strong supporters who did not want to make up. He then helped found the Irish Confederation on January 13, 1847.

The 1848 Rebellion and Escape

In the summer of 1847, Michael Doheny started "Confederate Clubs" in Tipperary. He also helped James Fintan Lalor create a group for farmers in Holycross.

Michael was one of the few Young Irelanders who liked Lalor's ideas about farmers' rights. But in January 1848, he supported Smith O'Brien over John Mitchel. Mitchel had called for a revolution. Michael's mind changed after Mitchel was found guilty of a serious crime in May. Michael was now ready to support a full rebellion. On July 12, he was arrested in Cashel for giving rebellious speeches. He was released on bail on July 20. This was nine days before the Young Ireland rebellion began. Michael tried to gather men in Tipperary. But William Smith O'Brien's hesitation held back his efforts.

After the fighting in Ballingarry on July 31 failed, Michael fled to the Mountain of Slievenamon. For the next two months, he avoided the police. He traveled across Munster with James Stephens. Michael finally escaped Ireland by dressing as a priest. He boarded a cattle ship from Cork to Bristol. From there, Michael went to Paris, France. He met Stephens again there. Another rebel, John O'Mahony, joined them. The three stayed in Paris for two months. Then they left for New York City.

Life in the United States

When Michael Doheny moved to the United States, he started working as a lawyer again. This helped him support himself. But he stayed active in Irish Republican groups. Many other Young Irelanders had also moved to New York. There were some disagreements between conservative and radical Young Irelanders in New York. One story tells of an argument between Michael and Thomas D'Arcy McGee. Some say McGee accused Michael of bragging and being clumsy. Michael then tried to push McGee down a cellar. Other accounts say Michael challenged McGee to a duel, but McGee refused. Michael then attacked McGee.

Michael also had another public fight in his first year in America. He argued with Patrick H. O’Conner about Daniel O'Connell's policies. After the event, they got into a fistfight in the street. A duel was planned, but O'Conner left for Ireland before it could happen.

In 1849, Michael wrote a book called The Felon's Track. It told the story of the repeal movement and the 1848 rebellion. Michael was very critical of O'Connell in the book. The book was quite popular and was printed many times. Michael became a popular speaker at Irish-American clubs. He also wrote a memoir about Geoffrey Keating. Keating was a 17th-century Irish historian from Michael's home county of Tipperary. Michael also helped John O'Mahony with his translation of a historical book called Foras Feasa ar Éirinn.

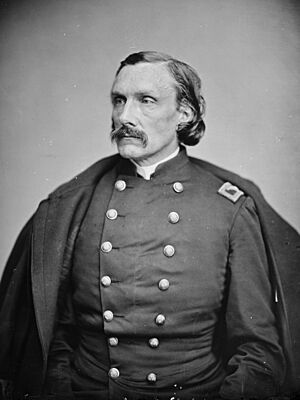

From the time he arrived in New York, Michael joined the city's Irish militias. In November 1851, he was elected a leader of the 69th New York Infantry Regiment. In September 1852, he became a leader of a new group called the Irish Republican Rifles. These Irish militias wanted Irish Independence. But they often had arguments about their plans and who should lead.

In February 1856, Michael Doheny and O'Mahony started the Emmet Monument Association. This group publicly said it wanted to fund a monument to Irish rebel leader Robert Emmet. But their secret goal was to unite Irish Republicans in America. When the Crimean War started in March 1857, Michael and O'Mahony met with the Russian consul in New York. They wanted Russia to support another rebellion in Ireland. They asked for transport for 2,000 men and weapons for 5,000 more. The request was sent to Russia. There was some interest, but Russia decided the plan was too expensive. This failure made many Irish-American groups lose hope. Some of them broke apart.

Michael Doheny and O'Mahony then contacted James Stephens in late 1857. Stephens agreed to help them. But he asked to be the undisputed leader of any new group. Stephens had just founded the Irish Republican Brotherhood on March 17, 1858. Michael and O'Mahony agreed to organize its American branch, the Fenian Brotherhood, in early 1859. At the same time, Michael started a short-lived newspaper called The Phoenix. It spread the ideas of the new Fenian movement.

Michael helped arrange the funeral for Terence Bellew MacManus in Ireland. He was one of the pallbearers at a ceremony in New York. Michael traveled to Ireland in October 1861 with the body. He was very happy to see large crowds. They honored MacManus and cheered for "Colonel" Doheny. Michael was so encouraged that he argued for another rebellion in Ireland. But James Stephens overruled this idea. After the funeral, Michael made an emotional visit to Cashel in Tipperary. He received a hero's welcome there.

Michael Doheny's Death

Not long after the MacManus funeral, Michael Doheny died suddenly on April 1, 1862. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York.

Michael Doheny's Writings

Michael Doheny is best known for his book, The Felon's Track. You can read it online here: Text at Project Gutenberg. He also wrote two poems: "Achusha gal machree" and "The Outlaw's Wife."