Thomas Devin Reilly facts for kids

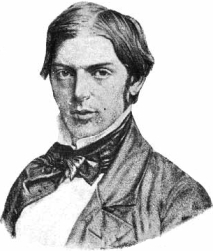

Thomas Devin Reilly (also known as Tomás Damhán Ó Raghailligh) was an Irish revolutionary, a member of the Young Irelander movement, and a journalist. He lived from 1824 to 1854 and played an important role in Irish politics during his short life.

Contents

Early Life and the Young Ireland Movement

Thomas Devin Reilly was born in Monaghan Town on March 30, 1824. His father, Thomas Reilly, was a lawyer. Thomas Devin Reilly went to school in Dublin and later studied at Trinity College, Dublin in 1842.

When he was 21, in 1845, Devin Reilly started working for a newspaper called The Nation. He wrote many articles for them. The editor, Charles Gavan Duffy, described him as a strong, honest, and smart young man. He said Devin Reilly was "a big, clumsy, careless, explosive boy in appearance, but he possessed a range of ideas and a vigour of expression which made him a companion for men."

Devin Reilly wrote a well-known review of a book by French historian Louis Blanc. Another writer, John Savage, said Devin Reilly's writing was so powerful it put him "into a front rank."

Joining the Irish Confederation

Devin Reilly was a founding member of the Irish Confederation. This group wanted to achieve more independence for Ireland. He left Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association in 1846 because he felt they weren't doing enough.

He gave two strong speeches to the Confederation. James Fintan Lalor was very impressed by these speeches. He wrote that Devin Reilly "ought to be the foremost man in the Confederation."

Working with John Mitchel

Devin Reilly became very close friends with John Mitchel, another Young Irelander. Both of them felt that the Confederation's peaceful approach wasn't working. In late 1847, Mitchel left The Nation and the Confederation. Devin Reilly quickly followed him.

In February 1848, Devin Reilly joined Mitchel's new newspaper, The United Irishman. This newspaper supported using force to gain Irish independence. One of Devin Reilly's most famous articles was "The French Fashion." Mitchel called it "one of the most telling revolutionary documents ever penned."

The United Irishman only lasted for 16 issues before the government shut it down. Mitchel was arrested. Devin Reilly was also briefly arrested but was released without charges.

The 1848 Rebellion

After The United Irishman was closed, Devin Reilly wrote for John Martin's newspaper, The Irish Felon. He continued to support the idea of using force for Irish freedom until this newspaper was also shut down.

In July 1848, Devin Reilly was chosen to be part of a five-person group leading the Confederate Clubs. They were planning a rebellion. He traveled through Kilkenny and Tipperary with leaders like William Smith O'Brien and Michael Doheny. He helped gather men for the Young Ireland Rebellion in Ballingarry, County Tipperary.

After the rebellion failed, Devin Reilly secretly escaped to America. He left Dublin disguised as a groom and arrived in New York City in December 1848.

Life in America

When he arrived in New York, Thomas Devin Reilly quickly became involved in American politics. He continued to support Irish independence from afar.

He is believed to have started a newspaper called The People in New York City in 1849. However, it only lasted for six months.

Some sources say Devin Reilly was an editor for the United States Magazine And Democratic Review and later the Washington Union. He was seen as a pioneer in American labor journalism, writing about workers' rights.

Thomas Devin Reilly died in 1854 when he was only 30 years old. He is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, D.C.. His infant child, Mollie, and his wife, Jennie Miller, are buried with him.

Important Ideas

Thomas Devin Reilly was a powerful speaker and writer. He believed that the Irish people were being treated unfairly.

In a speech in 1847, he told the Irish Confederation that they were "slaves" and needed to "open your eyes to your own abasement." He urged them to fight for their freedom and dignity. He said that even if they failed, their brave fight would be remembered as a "grand example of patriotism and manhood."

In 1848, writing in The Irish Felon, he discussed the workers' uprising in France. He stated that people willing to work should not be forced to starve. He believed that workers would keep fighting until they achieved true equality.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |