Battle of Assaye facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Assaye |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Anglo-Maratha War | |||||||

Major General Wellesley (mounted) commanding his troops at the Battle of Assaye (J.C. Stadler after W. Heath) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Arthur Wellesley | Anthony Pohlmann Raghoji II Bhonsle Daulatrao Scindia |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,500 (including two British infantry regiments and one cavalry regiment) 17 cannon |

10,800 European trained Indian infantry 10,000–20,000 Irregular Infantry 30,000–40,000 Irregular Cavalry 100+ cannon |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 428 killed 1,138 wounded 18 missing |

Total casualties of 6,000 killed and wounded or 1,200 confirmed killed and many more wounded, 98 cannons lost |

||||||

The Battle of Assaye was a very important battle during the Second Anglo-Maratha War. It happened on September 23, 1803, near a place called Assaye in western India. In this battle, a smaller force of Indian and British soldiers, led by Major General Arthur Wellesley, defeated a much larger Maratha army. Wellesley later became the famous Duke of Wellington.

This battle was Wellesley's first big victory. He even said it was his greatest achievement on the battlefield. He felt it was more impressive than his later wins in the Peninsular War or even defeating Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo.

For several weeks before the battle, Wellesley's army chased the Maratha army. The Marathas were known for their fast cavalry (soldiers on horseback). They had been threatening to attack the region of Hyderabad. The Maratha army then got stronger when their leader, Scindia, added modern infantry and artillery.

Wellesley found out where the Maratha camp was on September 21. He planned for his two armies to attack together a few days later. However, Wellesley's force found the main Maratha Army sooner than expected. It was led by Colonel Anthony Pohlmann, a German who used to work for the British. Even though Wellesley's army was outnumbered, he decided to attack right away. He thought the Maratha army might leave if he waited. Both sides suffered many losses. Maratha artillery (big guns) caused many casualties for Wellesley's troops. But the large number of Maratha cavalry did not help much. Finally, a mix of bayonet (knives on rifles) and cavalry charges made the Maratha army retreat. They lost most of their guns. However, Wellesley's army was too tired to chase them.

Wellesley's win at Assaye, along with other victories, led to the defeat of the Maratha armies in the Deccan region. These wins helped the British become the most powerful force in the heart of India.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

At the start of the 1800s, two powerful groups within the Maratha Empire were fighting each other. These were led by Yashwant Rao Holkar and Daulat Rao Scindia. Their fighting led to a civil war. In October 1802, Holkar defeated Scindia and Baji Rao II, who was the leader of the Maratha Empire.

Baji Rao ran away and asked the East India Company for help. He offered to let the Company control his foreign affairs if they put him back in power. Lord Mornington, who was the Governor-General of British India, saw this as a chance. He wanted to expand British power in India.

A treaty was signed in December 1802, called the Treaty of Bassein. The Company agreed to help Baji Rao. In return, they would control his foreign matters and keep 6,000 Company soldiers in Poona. Lord Mornington's younger brother, Major General Arthur Wellesley, led the troops to put Baji Rao back on his throne. Wellesley entered Poona without a fight in April 1803.

Other Maratha leaders were not happy about this treaty. They felt it was the British interfering too much. Tensions grew when Holkar attacked Hyderabad, a British ally. Wellesley, who was in charge of British military and political matters in central India, demanded that Scindia explain his actions. He told Scindia to pull back his troops or face war. After long talks, Scindia refused. So, Wellesley declared war on Scindia and the Raja of Berar. He said it was "to secure the interests of the British government and its allies."

Getting Ready for Battle

The East India Company decided to attack the two main Maratha forces. These were led by Scindia and the Raja of Berar. British forces attacked from both the north and the south. Another Maratha leader, Holkar, stayed out of the fight.

In the south, Major General Arthur Wellesley faced a combined army of Scindia and Berar. Wellesley wanted to attack first. He told his officer, Colonel James Stevenson, that a long defensive war would be bad for them.

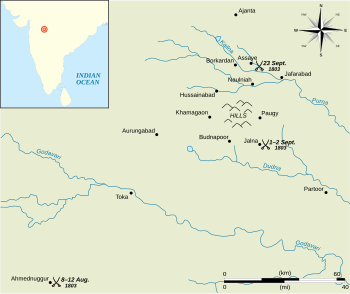

The Maratha army in the Deccan was mostly fast-moving cavalry. Wellesley planned to work with Colonel Stevenson's separate force. This would help his slower troops outmaneuver the Maratha army. He wanted to force them into a big battle they could not avoid. Stevenson went to Jafarabad to stop Scindia and Berar from attacking the Nizam's land.

Meanwhile, Wellesley moved north from the Godavari River in August. He had about 13,500 troops. He headed towards Scindia's stronghold, the town and fort of Ahmednagar. Most of his soldiers were from the Company. These included Indian infantry (foot soldiers) and cavalry. He also had British Army soldiers, like cavalry and Scottish infantry. Allies from Mysore and the Marathas provided light cavalry.

Wellesley reached Ahmednagar the same day. He immediately ordered an attack on the town walls. The town was defended by 1,000 Arab fighters and many cannons. It was captured quickly with few losses. The nearby fort surrendered four days later. With Ahmednagar as a supply base, Wellesley moved north. He captured Scindia's other lands south of the Godavari River. He also set up bridges and ferries to keep his supplies moving.

Maratha Army Gets Stronger

The Marathas managed to get past Stevenson and moved towards Hyderabad. Wellesley heard about this on August 30 and rushed to stop them. Stevenson, meanwhile, attacked the Maratha city of Jalna and captured it. Scindia learned of Wellesley's plans and moved back north of Jalna. He gave up on raiding Hyderabad and gathered his infantry and artillery.

The combined Maratha army was very large, about 50,000 strong. The main part was 10,800 well-trained infantry soldiers. These were organized into three groups, led by European officers. Colonel Anthony Pohlmann, a German, commanded the largest group. The Maratha force also had 10,000 to 20,000 irregular infantry. They had 30,000 to 40,000 irregular light cavalry. Plus, they had over 100 cannons of different sizes.

After weeks of chasing the Maratha army, Wellesley and Stevenson met on September 21. They learned the Maratha army was about 30 kilometers north. They agreed to attack on September 24, moving separately on either side of some hills. Wellesley's force reached Paugy on September 22. They marched 14 kilometers to Naulniah, a small town south of Borkardan. They planned to rest there. But then, Wellesley got new information. The Maratha army was only 5 kilometers north, not 12 kilometers. Their cavalry had moved, and the infantry was about to follow.

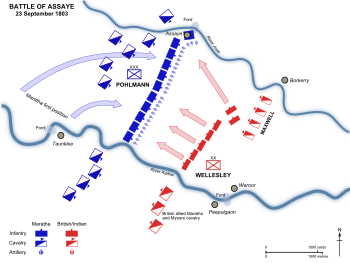

Around 1:00 PM, Wellesley went ahead with some cavalry to check the Maratha position. The rest of his army followed. Wellesley had 4,500 troops, plus 5,000 allied cavalry and 17 cannons. The Maratha leaders had placed their army in a strong defensive spot. It was on a piece of land between the Kailna River and another river called the Juah. However, Scindia and Berar did not think Wellesley would attack with such a small force. They had left the area that morning. Command of their army was given to Pohlmann. He had placed his infantry near the village of Assaye on the Juah River.

Wellesley was surprised to see the entire Maratha army there. But he decided to attack right away. He believed that if he waited for Stevenson, the Marathas would get away. Wellesley also wanted to prove himself. Even though he was outnumbered, he was confident his well-trained troops could defeat the Maratha irregular forces. He thought only Scindia's regular infantry would truly fight.

The Battle Begins

Pohlmann moved his camp and lined up his infantry soldiers. They faced south, behind the steep banks of the Kailna River. His cannons were placed right in front of them. Most of the Maratha cavalry stayed on the right side. Berar's irregular infantry guarded Assaye behind them. The only easy way to cross the river was a small ford right in front of the Maratha position. Pohlmann wanted to force the British and Madras troops to cross this ford. This would make them easy targets for his cannons, infantry, and cavalry.

While checking the area, Wellesley noticed two villages, Peepulgaon and Waroor. They were on opposite banks of the Kaitna River, beyond the Maratha left side. He thought there must be a ford between them. Wellesley sent his Chief Engineer, Captain John Johnson, to check. Johnson reported that there was indeed a ford there. So, Wellesley led his army east to this crossing. He planned to attack Pohlmann's left side.

Around 3:00 PM, the British crossed to the north side of the Kaitna River. There was no resistance except for some distant cannon fire from the Marathas. This fire was mostly inaccurate. Once across, Wellesley told his six infantry groups to form two lines. His cavalry stayed behind as a reserve. His allied Maratha and Mysore cavalry stayed south of the Kaitna. They watched a large group of Maratha cavalry that was near the British rear.

Pohlmann soon realized what Wellesley was doing. He quickly turned his infantry and guns 90 degrees. They formed a new line about one kilometer long. Their right side was on the Kaitna River, and their left was at Assaye. This new position protected the Maratha sides. But it also stopped Pohlmann from using his larger numbers effectively.

The Maratha army moved faster than Wellesley expected. He quickly reacted by spreading out his own line. This stopped Pohlmann from getting around his sides. Two groups of soldiers, the pickets and the 74th Highlanders, moved to the right. This allowed the 78th to hold the left side. Other Madras infantry groups formed the center of the British line. Wellesley wanted to push the Marathas back from their guns. Then, he planned to push them towards the Juah River and destroy them with his cavalry.

British Soldiers Attack

The Maratha cannon fire got stronger as the British moved. British cannons were brought forward, but they were not strong enough against the many Maratha guns. The British cannons were quickly put out of action. British soldiers suffered more and more casualties. The Maratha guns then focused on the infantry. They fired many different types of cannonballs at them. Wellesley decided his only choice was to attack the Maratha artillery directly. He ordered his cannons to be left behind. He then commanded his infantry to march forward with their bayonets (knives on their rifles) ready.

The Maratha cannon fire created gaps in the British line. But the infantry kept moving steadily. They closed the gaps in their ranks as they advanced. The 78th Highlanders were the first to reach the enemy near the Kailna River. They stopped about 50 meters from the Maratha gunners. They fired their muskets once, then charged with bayonets. The four Madras infantry groups to the right of the 78th also attacked in the same way. The Maratha gunners tried to stand their ground. But they were no match for the bayonets of the British and Madras troops. These soldiers quickly moved past the guns towards the Maratha infantry.

However, the Maratha right side broke and ran north towards the Juah River. This caused the rest of the southern part of their line to follow. The officers of the Madras groups briefly lost control. Their soldiers, excited by their success, chased too far. Maratha cavalry briefly threatened to attack. But the 78th, who stayed in order, stopped them.

On the northern side of the battlefield, Wellesley's right side was in trouble. The commander of the pickets, Lieutenant Colonel William Orrock, misunderstood his orders. He kept moving directly towards Assaye. Major Samuel Swinton of the 74th Regiment was ordered to support the pickets and followed closely. This created a large gap in the middle of the British line. Both groups came under heavy cannon fire from the village and the Maratha left. The two groups began to fall back in confusion. Pohlmann ordered his remaining infantry and cavalry to attack. The Marathas showed no mercy. The pickets were almost completely wiped out. But the remaining 74th soldiers managed to form a rough square behind piles of dead bodies.

Wellesley realized that if his right side was destroyed, his army would be exposed. He ordered British cavalry, led by Colonel Patrick Maxwell, to attack. This group included the 19th Light Dragoons and parts of the 4th and 5th Madras Native Cavalry. From their position at the back, the cavalry rushed towards the 74th's square. They crashed into the attacking Marathas and made them run away. Maxwell kept pushing his advantage. He continued his charge into the Maratha infantry and guns on the right. He drove them backward and across the Juah River, causing many losses.

The Battle Ends

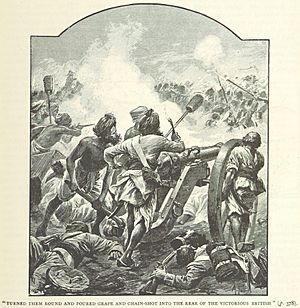

Some Maratha gunners had pretended to be dead when the British advanced. They now got back to their guns. They started firing cannons into the back of the 74th and Madras infantry. Wellesley ordered his four sepoy (Indian soldier) groups to get back into formation. They were to guard against any threat from the Maratha infantry and cavalry. The 78th were sent back to retake the Maratha gun line. Meanwhile, Wellesley rode back to the 7th Madras Native Cavalry. This group had been held back as a reserve. He led a cavalry charge from the other direction. The gunners again stood their ground. But they were eventually driven from their guns. This time, it was made sure that all who remained were dead.

While Wellesley was busy retaking the gun line, Pohlmann gathered his infantry. He reformed them into a semicircle with their backs to the Juah River. Their right side was across the river, and their left was in Assaye. However, most of the Maratha cannons, which had caused many losses for Wellesley's infantry, had been captured or left behind. The Maratha cavalry stayed in the distance to the west. Most of them were Pindarries. These were loosely organized horsemen. Their job was usually to chase fleeing enemies, attack supply lines, and raid enemy lands. They were not trained to attack well-formed infantry or heavily armed European cavalry. They did not take part in the rest of the battle.

With the Maratha artillery silenced, Wellesley focused on Pohlmann's reformed infantry. Although Maxwell's cavalry had suffered many losses, he had gathered his soldiers and returned to the battlefield. Wellesley ordered him to charge the Maratha left side. The infantry moved forward as a single line to meet the center and right. The cavalry charged forward. But they were met with a volley of cannon fire that hit Maxwell, killing him instantly. The cavalry lost their momentum. They did not complete their charge. Instead, they turned away from the Maratha line at the last moment.

The British and Madras infantry marched on against the Maratha position. Pohlmann's men, with low morale, did not wait for the attack. Instead, they retreated north across the Juah. Maratha sources say the line marched away in an orderly way on Pohlmann's orders. But British accounts say the Maratha infantry fled in an uncontrolled panic. Berar's irregulars inside Assaye, now without a leader, left the village around 6:00 PM. The Maratha cavalry followed shortly after. Wellesley's troops were exhausted and could not chase them. The allied cavalry, who had stayed on the south bank of the Kailna and had not fought, refused to chase without the support of the British and Madras cavalry.

What Happened After

The East India Company and British Army lost many soldiers. A total of 1,584 were killed, wounded, or missing. This was over a third of their fighting force. The 74th and the picket battalion were almost destroyed. The 74th lost ten officers killed and seven wounded. They also lost 124 other soldiers killed and 270 wounded. The pickets lost all their officers except their commander. Of Wellesley's ten staff officers, eight were wounded or had their horses killed. Wellesley himself lost two horses. One was shot, and the second was speared as he led the charge to retake the Maratha gun line.

It is harder to know how many Maratha soldiers were lost. British officers reported 1,200 dead and many more wounded. But some historians think the total was 6,000 dead and wounded. The Marathas also lost seven flags, many supplies, and 98 cannons. Most of these cannons were later used by the East India Company. Although Scindia and Berar's army was not completely destroyed, some of Scindia's regular infantry groups and artillery crews were gone. Their command structure was also damaged. Many of their European officers surrendered or left.

Stevenson heard the sound of the guns at Assaye. He immediately left his camp about 10 kilometers west to join the battle. However, his guide led him the wrong way. He reached the battlefield on the evening of September 24. Stevenson suspected his guide had tricked him and later had him hanged. He stayed with Wellesley to help with the wounded. Soldiers were still being carried from the battlefield four days after the fight. Stevenson was then ordered to continue chasing the Maratha army on September 26. Wellesley stayed south to set up a hospital. Two months later, he joined Stevenson to defeat Scindia and Berar's weakened army at Argaon. Soon after, they attacked Berar's fort at Gawilghur. These victories, along with other British successes, made the two Maratha chiefs ask for peace.

Wellesley later told Stevenson that he would not want to see such losses again, even with such a victory. Later in his life, he called Assaye "the bloodiest for the numbers that I ever saw." Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Munro questioned Wellesley's decision not to wait for Stevenson. He wrote to Wellesley, suggesting he attacked to share the glory with fewer people. Wellesley politely disagreed. He said his actions were necessary because he had received incorrect information about the Maratha position. Assaye was 34-year-old Wellesley's first big success. Despite the heavy losses, he always thought very highly of this battle. After he retired from the military, the Duke of Wellington (as he became known) considered Assaye the finest thing he ever did in fighting.

Lord Mornington and his Council called the battle a "most brilliant and important victory." They gave each of the Madras units and British regiments involved special flags. The British regiments and Indian units also received the Assaye battle honour. Most were later allowed to use an Assaye elephant as part of their symbol. A public monument was also built by the East India Company in Fort William, Calcutta, to remember the victory. The 74th Regiment of foot became known as the Assaye regiment because of their stand in the battle. Their modern-day successors still celebrate the battle's anniversary each year. Of the Indian infantry groups, only the Madras Sappers still exist in their original form in the Indian Army. However, they no longer celebrate Assaye.

In Fiction

- The fictional character Richard Sharpe, created by Bernard Cornwell, became an officer by saving Wellesley's life at the Battle of Assaye. The book Sharpe's Triumph describes the campaign and battle in detail. Both men remember Assaye many times throughout the series as their careers continue. The TV show version is different. It shows Sharpe saving Wellesley's life from French soldiers in Spain during a later war.