Nestor Makhno facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nestor Makhno

|

|

|---|---|

|

Не́стор Махно́

|

|

|

|

| Otaman of the Makhnovshchina | |

| In office 30 September 1918 – 28 August 1921 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Viktor Bilash |

| Chairman of the Military Revolutionary Council | |

| In office 27 July 1919 – 1 September 1919 |

|

| Preceded by | Ivan Chernoknizhny |

| Succeeded by | Volin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 8 November [O.S. 27 October] 1888 Huliaipole, Oleksandrivsky, Katerynoslav, Russian Empire |

| Died | 25 July 1934 (aged 45) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery, Columbarium niche 6685 |

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Height | 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) |

| Spouse | Halyna Kuzmenko |

| Children | Elena Mikhnenko |

| Parents |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1918–1921 |

| Rank | Commander-in-chief |

| Battles/wars | Ukrainian War of Independence |

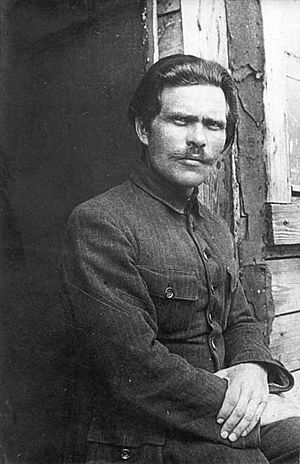

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno (born November 8, 1888 – died July 25, 1934) was a Ukrainian anarchist leader. He was also known as Bat'ko Makhno, which means "Father Makhno". He led the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine during the Ukrainian Civil War.

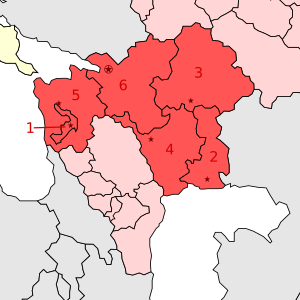

Makhno's name is linked to the Makhnovshchina, a movement mostly made up of peasants. It started in his hometown of Huliaipole. This movement grew to be very important in southern Ukraine during the war. Makhno and most of his group believed in anarcho-communism. They tried to organize society based on these ideas.

Makhno strongly opposed anyone trying to control southern Ukraine. He fought against many groups, including the Ukrainian People's Republic, the Central Powers, the White Army, and the Red Army. He also fought other local leaders. Makhno and his followers wanted to change how society worked. They set up communes on large farms, shared land fairly with peasants, and held free elections for local councils. However, the ongoing war made it hard to create lasting changes.

Makhno saw the Bolsheviks as a threat to anarchism in Ukraine. Still, he teamed up with the Red Army twice to defeat the White Army. After the White Army was beaten in November 1920, the Bolsheviks turned against Makhno. He fought them for a long time before leaving Ukraine in August 1921. Makhno lived in Paris with his wife Halyna and daughter Elena. He wrote many articles and memories during this time. He also helped develop platformism, a way of organizing anarchists. Makhno passed away in 1934 at age 45 from health issues.

Contents

Nestor Makhno's Early Life

Nestor Makhno was born on November 8, 1888, in Huliaipole, Ukraine. His family was very poor. He was the youngest of five children. His parents were former serfs, who were freed in 1861.

Nestor's father worked as a coachman to support the family. But his father died when Nestor was only ten months old. This left his family in great poverty. Nestor was briefly cared for by another family. However, he was unhappy and returned home. At seven years old, he started working with livestock. When he was eight, he began school. He was a good student at first. But he started skipping school to play and ice skate. After his first school year, he worked on a farm. He earned 20 rubles that summer. His brothers also worked to help the family.

Nestor went back to school, but his second year was his last. His family's extreme poverty forced him to work full-time in the fields at age ten. This made him feel angry towards wealthy landowners. His mother's stories about being a serf also fueled this feeling. In 1902, Nestor saw a farm manager beating a young worker. He quickly told an older stable hand, "Batko Ivan." Ivan helped the worker and led a small protest. Ivan told Nestor to fight back if a master ever hit him. The next year, Nestor left farm work and found a job in a foundry. He moved between jobs, often helping on his mother's land.

Becoming a Revolutionary Leader

When the 1905 revolution began, 16-year-old Makhno quickly joined in. He first shared information for the Social Democratic Labor Party. Then he joined his hometown's anarchist group, the Union of Poor Peasants. Even with strict rules against revolutionaries, the Union met weekly. This inspired Makhno to dedicate himself to the revolution. At first, other members didn't trust him because he often got into fights. But after six months, Makhno learned a lot about libertarian communism and became a full member.

After new land laws created a wealthier land-owning class, the Union of Poor Peasants started taking money from local business owners. They used this money to print materials that criticized the new laws. Makhno was suspected of being involved and was arrested in September 1907. But he was released because there wasn't enough proof. Since other group members were in hiding, Makhno started another anarchist study group. Two dozen members met weekly to discuss anarchist ideas. However, after a police informant was harmed, police cracked down on the group. Many members, including Makhno, were arrested in August 1909.

Time in Prison

On March 26, 1910, Makhno was sentenced to be executed. But because he was young, his sentence was changed to life in prison with hard labor. While in prison, Makhno became very sick with typhoid fever. He recovered but had to work in chains. He was moved to different prisons. In August 1911, he was sent to Butyrka prison in Moscow. Over 3,000 political prisoners were there. He learned about Russian history and political ideas from other prisoners. He especially liked Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution by Peter Kropotkin. Makhno was sometimes put in solitary confinement for bothering guards. These conditions made him sick again with Tuberculosis.

In Butyrka prison, Makhno met Peter Arshinov, an anarchist leader. Arshinov became Makhno's teacher. Makhno also started to feel less interested in purely academic ideas. He saw how prison guards treated intellectual prisoners differently from working-class inmates. As years passed, Makhno wrote his own works. He shared a poem called Summons that called for a revolution. Prison did not stop his revolutionary spirit. He vowed to help his country become free. He learned about Ukrainian nationalism in prison but remained against all forms of nationalism. He opposed World War I and even circulated an anti-war petition. When the prison doors opened during the February Revolution of 1917, Makhno was free after eight years. He stayed in Moscow for three weeks. Then he returned to Huliaipole in March, convinced by his mother and old friends.

Helping Farmers and Workers

In March 1917, 27-year-old Makhno returned to Huliaipole. He was happy to see his mother and brothers. Many peasants greeted him, curious about the famous political figure. Makhno suggested that anarchists should lead the people to action. He helped create a local Peasants' Union on March 29 and became its chairman. This union quickly represented most peasants in the area. Carpenters and metalworkers also formed unions and chose Makhno as their chairman. By April, the local government in Huliaipole was controlled by peasants and anarchists. During this time, Makhno met Nastia Vasetskaia, who became his first wife. But his busy work kept him from focusing on his marriage.

Makhno quickly became a key figure in Huliaipole's revolution. He wanted to keep political parties from controlling workers' groups. He saw his leadership as a temporary duty. As a union leader, Makhno helped workers go on strike for better wages. He promised more strikes if their demands were not met. This led to workers taking control of all industries in Huliaipole. Makhno was a delegate to a peasant meeting in Oleksandrivsk. He called for taking large estates from landowners and giving them to peasants to share. This made him well-known in the region. However, he disliked the long debates and party politics at the meeting. He felt Huliaipole was already doing what the congress was only talking about.

Makhno then reduced the power of local police. He also took land from landlords and shared it equally among peasants. This went against the Russian Provisional Government. People saw him as a hero, comparing him to old Cossack rebel leaders. They rallied around the slogan "Land and Liberty".

Makhno was disappointed by the lack of organization in the wider anarchist movement. He felt it focused too much on talking. Despite growing, the movement couldn't compete with established political parties. It needed a better way to lead the revolution. After a failed attempt to overthrow the Provisional Government, Makhno helped create a "Committee for the Defense of the Revolution" in Huliaipole. This group organized armed peasants against landlords and wealthy farmers. Makhno called for taking weapons from the wealthy and putting all businesses under workers' control. Peasants stopped paying rent and took control of the land they worked. Large farms became shared communities. Makhno personally helped set up these communities. He and Nastia lived on one, and he worked two days a week helping with farming and fixing machines.

After the 1917 October Revolution, Makhno saw growing conflict between Ukrainian nationalists and the Bolsheviks. When the Soviet–Ukrainian War started, Makhno advised anarchists to fight with the Red Guards against the Ukrainian nationalists. Makhno sent his brother Savelii with an armed anarchist group to help the Bolsheviks take back Oleksandrivsk. The city was taken, and Makhno was chosen to represent anarchists on the Oleksandrivsk Revolutionary Committee. He also led a group that reviewed cases of accused military prisoners. He helped free imprisoned workers and peasants. Makhno also helped defend Oleksandrivsk against an attack by Don Cossacks. He then returned to Huliaipole. There, he organized taking money from the town bank to fund their revolutionary work.

Travels to Moscow

In February 1918, Ukrainian leaders signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers. This led to German and Austro-Hungarian forces invading Ukraine. Makhno formed a group to resist this. He went to join the Red Guards in Oleksandrivsk. But he couldn't meet with the Bolshevik commander, who was quickly retreating. While Makhno was away, Ukrainian nationalists took control of Huliaipole. They invited Austro-Hungarian forces to occupy the town in April 1918. Makhno couldn't go home. He went to Taganrog, where exiled anarchists from Huliaipole met. Makhno decided to seek support in Russia to take back Huliaipole in July 1918. In early May, he visited several cities. He briefly reunited with Nastia and friends from Huliaipole.

During his travels, Makhno saw the new secret police, the Cheka, disarming and harming revolutionary fighters who didn't follow their orders. This made Makhno wonder if "official revolutionaries" would stop the revolution. In Astrakhan, Makhno worked for the local council's information department. He gave speeches to Red soldiers going to the front lines. In late May, while traveling by train to Moscow, Makhno used the train's weapons to help it escape from attacking Cossacks.

After a few days, Makhno arrived in Moscow. He called it "the capital of the paper revolution." He felt that local anarchist thinkers were more interested in words than actions. He met Peter Arshinov and other anarchists. Many were watched by the Bolshevik government. He also met the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, who were starting to oppose the Bolsheviks. Makhno talked about Ukraine with the anarchist thinker Peter Kropotkin, who wished him well.

Makhno was satisfied with his time in Moscow. He needed fake papers to cross the Ukrainian border. He went to the Kremlin. Yakov Sverdlov quickly arranged for Makhno to meet Vladimir Lenin. Lenin asked Makhno many questions about Ukraine. Makhno answered them, even when Lenin said Ukraine's peasants were "influenced by anarchism." Makhno strongly defended the Ukrainian anarchist movement. He criticized the Red Guards for staying on the railways while peasant fighters fought on the front lines. Lenin admired Makhno and admitted he had made mistakes about the situation in Ukraine. Anarchists were already a strong revolutionary force there. After a long talk, Lenin sent Makhno to Volodymyr Zatonsky, who gave him a false passport. Makhno left for the border in late June. He felt he had understood the "temperature of the revolution."

Leading the Makhnovist Movement

While Makhno was away, Austro-German forces took control in Ukraine in April 1918. They removed the old government and put Pavlo Skoropadskyi in charge.

Makhno returned to Ukraine in July 1918, disguised as an officer. He learned that the forces in Huliaipole had harmed many revolutionaries. His brother Savelii was arrested, and his disabled brother Omelian was killed. His mother's house was also destroyed. Nestor had to be very careful to avoid capture. He changed trains and even walked to avoid being recognized. His friends in Huliaipole warned him not to return, fearing he would be caught.

After weeks in hiding, Makhno secretly returned to Huliaipole. He held secret meetings to plan a rebellion. He wanted organized attacks on large estates, not individual acts of violence. He also forbade attacks on Jewish communities. Makhno stressed working together and waiting for the right time for a big uprising.

The authorities found out Makhno was back and offered a reward for his capture. Makhno left Huliaipole, barely escaping. In Ternivka, he gathered local peasants to fight against the occupation and the government. He worked with fighters in another village to take back Huliaipole. He attacked Austrian positions, taking weapons and money. This made the rebellion stronger. Makhno even went back to Huliaipole disguised as a woman. He planned to attack the occupation forces' command center. But he decided against it to avoid harming innocent people.

In September 1918, Makhno briefly took back Huliaipole. He found out that German forces had spread false rumors about him. They claimed he had stolen from peasants and ran away. After defeating Austrian units nearby, Makhno wrote a letter in German. It encouraged the soldiers to rebel, go home, and start their own revolutions. While his friends spread out to encourage peasants to revolt, Makhno prepared announcements that the region was under their control. However, when the occupation forces fought back, Makhno had to leave Huliaipole.

Makhno's group went north to the Dibrivka forest. There, they joined another small group led by Fedir Shchus. Austrian units surrounded them in the forest. To escape, Makhno launched a surprise attack on the troops in the village. Makhno and Shchus led the attack, forcing the Austrians to retreat. Because of his role in this victory, the fighters gave Makhno the title Bat'ko (Father). He kept this name for the rest of the war.

Makhno's victory led to a harsh response from the occupation forces. Velykomykhailovka was attacked by Austrian troops and others. The village was burned, killing many people and destroying hundreds of homes. Makhno, in turn, led attacks against the occupation forces and those who helped them. This included some of the Mennonite population in the region. Makhno also spent a lot of time talking to peasants. He gained much support by giving passionate speeches against his enemies in villages.

By November 1918, the fighters had fully recaptured Huliaipole. At a regional meeting, Makhno suggested fighting on four fronts at once. These were against the government, the Central Powers, the Cossacks, and the growing White movement. He argued that to do this, they needed to organize their army in a new way, with him as the main commander.

Working with the Red Army

When World War I ended, the Central Powers left Ukraine. This led to a new nationalist government in Kyiv. At the same time, the Bolsheviks invaded Ukraine from the north. The Makhnovshchina also faced pressure from the growing White Army in the south. Caught between these groups, Makhno suggested an alliance with the Red Army.

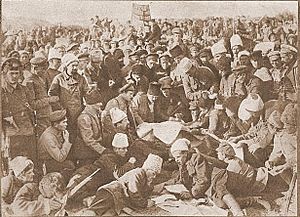

During a joint attack on the city of Katerynoslav, Makhno was made commander of the combined Soviet forces in the region. After taking the city, Makhno helped set up a local council with Bolsheviks, Socialists, and anarchists. When a nationalist counterattack forced Makhno to retreat, he completely reorganized his forces. On January 26, 1919, Makhnovist units joined the Ukrainian Soviet Army. Makhno reported to Pavel Dybenko. On February 12, 1919, Makhno left the front to attend a regional meeting in Huliaipole. He was chosen as honorary chairman. At the meeting, he supported "non-party soviets," which went against his Bolshevik commanders.

Makhno said joining the Red Army was necessary for the revolution. He still disliked the new political leaders. Bolshevik interference in military operations even led Makhno to arrest a Cheka group that had stopped his command. Despite his dislike for the Bolsheviks, Makhno believed in freedom of the press. He allowed Bolshevik newspapers to be given out in Huliaipole, even if they criticized his group.

By April 1919, the newspaper Pravda wrote good things about Makhno. It praised him for fighting Ukrainian nationalism and for his successes against the White movement. These reports also showed that Makhno had wide support among Ukrainian peasants. However, this didn't stop Pavel Dybenko from calling the Makhnovists' meetings "counter-revolutionary." Their participants were declared outlaws, and Makhno was told to stop future meetings. The Makhnovist military council strongly rejected Dybenko's demands.

To solve the disagreement, Makhno invited Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko to Huliaipole. The Ukrainian commander was impressed and felt better about Makhno's leadership. Antonov-Ovseenko praised Makhno and his fighters. He criticized the Bolshevik press for spreading false information. He also asked for needed equipment for the Makhnovists. His reports quickly led Lev Kamenev to visit Huliaipole the next week. Kamenev was greeted by Makhno and his new wife Halyna Kuzmenko. Kamenev published an open letter praising Makhno as an "honest and brave fighter."

In May 1919, a powerful local leader named Nykyfor Hryhoriv rebelled against the Bolsheviks. Kamenev sent a message to Makhno, asking him to speak against Hryhoriv. Hryhoriv had tried to form an alliance with Makhno earlier, but Makhno didn't respond. Makhno told Kamenev he was still committed to fighting the White movement. He worried that fighting Hryhoriv would put this at risk. Makhno declared his loyalty to the revolution. But he also said he would continue to oppose the actions of the Cheka and any other "groups of control and force." At a military meeting on May 12, Makhno spoke against the Bolsheviks. He criticized their control and their harsh methods, comparing them to the old government. After Makhnovist messengers found proof that Hryhoriv was involved in attacks on Jewish communities, Makhno openly spoke against him. He blamed Hryhoriv for his actions and also blamed the Bolsheviks for Hryhoriv's rise.

The Red Army leaders then tried to limit Makhno's power. A Red Army commander even said Makhno should be "removed." By the end of May 1919, the Bolshevik military council declared Makhno an outlaw. They issued a warrant for his arrest. On June 2, Leon Trotsky wrote a strong criticism of Makhno. He attacked Makhno's ideas and called him a "wealthy farmer."

A few days later, Makhno learned that Cossacks had taken Huliaipole. This forced him to retreat. To try and calm Trotsky, Makhno stepped down from his command. He wanted to avoid his fighters being caught between the Red and White armies. Despite Trotsky's rejection, he tried again to resign on June 9. He restated his commitment to the Revolution and the rights of workers and peasants. Makhno then left command of his division. He said he would fight the Whites using guerrilla tactics. Trotsky then ordered Makhno's arrest. But friendly officers warned Makhno, preventing his capture. Even though he had left the Red Army, Makhno still saw the White movement as his main enemy. He believed they could deal with the Bolsheviks after the Whites were defeated.

Makhno's small group then joined other rebel groups that had left the Red Army. In early July 1919, Makhno went to another province. There, he met with Hryhoriv's group. Makhno initially wanted to form an alliance with Hryhoriv because he was popular with local peasants. However, when they found out about Hryhoriv's actions against Jewish communities and his ties to the White movement, the Makhnovists spoke out against him. When Hryhoriv reached for his weapon, he was shot by Oleksiy Chubenko. After this, Makhno quickly rebuilt his army. Part of Hryhoriv's army joined Makhno's forces, which grew to about 20,000 fighters. By August, many Red Army soldiers who left their units also joined Makhno. The Bolsheviks were retreating from Ukraine because of Anton Denikin's White Army. Red Army desertions became so common that a Ukrainian Bolshevik leader called Makhno. He begged Makhno to rejoin Bolshevik command, but Makhno refused.

Fighting the White Army

By September 1919, the Bolsheviks had mostly left Ukraine. This left the Makhnovists to face the White Army alone. Reports from a White commander described Makhno as a strong opponent. He noted Makhno's good tactics and control over his troops. Makhno's fighters launched effective attacks behind White lines. Makhno himself led a cavalry attack that captured much-needed supplies. Nestor's brother Hryhorii died during one of these attacks.

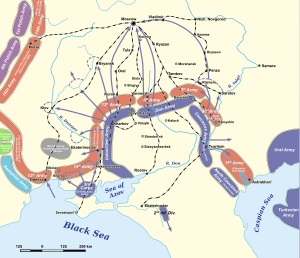

The White offensive pushed Makhno's fighters back to Uman. This was the last stronghold of the Ukrainian People's Republic. There, Makhno made a temporary agreement with Symon Petliura. This allowed wounded fighters to recover before a counterattack. During the Battle of Perehonivka, the battle turned in Makhno's favor. Makhno led his group in a surprise move against the White positions. They charged the larger enemy force, fighting them up close. This forced the Whites to retreat. Makhno then chased the retreating Whites, defeating them decisively. Only a few hundred survived. The Makhnovists then split up to take as much land as possible. Makhno himself led his group to capture Katerynoslav from the Whites on October 20. With southern Ukraine almost entirely under Makhnovist control, the White supply lines were broken. Their advance on Moscow was stopped. The Makhnovist advance also led to attacks against the region's Mennonites. This included the Eichenfeld massacre. While some blame Makhno directly, others say the attacks were due to long-standing tensions between Ukrainians and Mennonite settlers.

Bolsheviks in Katerynoslav tried to set up a local council to control the city. They suggested Makhno only focus on military actions. But Makhno no longer trusted the Bolsheviks. He called them "parasites." He quickly ordered the council to be shut down. He forbade their activities, telling Bolshevik officials to "find a more honest job." At a regional meeting, Makhno presented a plan for "free soviets" not controlled by political parties. Some delegates disagreed, believing in the old assembly. Makhno called them "counter-revolutionaries," and they left. When he returned to Katerynoslav on November 9, railway workers asked Makhno for their unpaid wages. He suggested the workers manage the railways themselves and collect payment directly from customers. By December 1919, Makhnovist control of Katerynoslav weakened due to attacks from White Cossacks. On December 5, Makhno survived an attempt to harm him by Bolsheviks. After the plot was discovered, those involved were dealt with.

New White attacks forced the Makhnovists to leave Katerynoslav. They retreated towards other towns. During this time, many fighters got sick with typhus. Even Makhno got sick and fell into a long coma. Local peasants hid him from the secret police. Once he recovered, Makhno began fighting the secret police and groups taking supplies.

Makhno also had a policy for captured Red Army units. Officers and political leaders would be immediately dealt with. Regular soldiers could choose to join his army or be sent home without their uniforms. With the Makhnovists causing problems for the Bolsheviks, and Red Army soldiers joining Makhno, talks for an alliance began.

Makhno was unsure about a Bolshevik alliance in June. But he became more open to it. His army voted for it in August. The agreement gave Ukrainian anarchists certain freedoms. It also put Makhno's fighters under Red Army command. Despite this, Makhno still distrusted the Bolshevik Party. He said the military alliance shouldn't be confused with accepting their authority. Still, Makhno hoped that defeating the Whites would make the Bolsheviks respect his desire for soviet democracy and civil liberties in Ukraine. He later called this a "big mistake."

Under the agreement, Makhno finally got medical help from the Red Army. Doctors treated a wound in his ankle. He was also visited by a Hungarian communist leader, who gave him gifts. On October 22, Makhno's fighters took back Huliaipole from the Whites for the last time. Back home, Makhno asked for three days of rest. But the Bolshevik command refused. They ordered his fighters to continue fighting, or their alliance would end. The still-wounded Makhno stayed in Huliaipole with his guard. He sent Semen Karetnyk to lead the attack against the Army of Wrangel. Makhno again focused on rebuilding his vision of anarcho-communism. He oversaw the reestablishment of the local council and other anarchist projects.

Fighting the Bolsheviks

The defeat of Wrangel's army by Bolshevik-Makhnovist forces ended the war in the south. This allowed the Bolsheviks to turn on their anarchist allies again. In late November 1920, the Red Army launched a surprise attack on Makhno's forces. They surrounded Huliaipole. Caught off guard, Makhno gathered 150 guards to defend the town. He found a gap in the Red lines and escaped with his group. He led a counterattack that pushed the Red forces back. His forces regrouped and gained some Red soldiers who joined them. They recaptured Huliaipole a week later. The Red Army said they attacked Makhno because he refused orders and planned to betray them. However, the Red Army had planned to break the alliance even before the fight against Wrangel's army began.

The next week, Makhno reunited with Karetnyk's group. It was much smaller and its commander was no longer with them. Despite orders from Vladimir Lenin to "remove Makhno," the fighters continued their guerrilla campaign. On December 3, Makhno led 4,000 fighters in an attack that defeated a Red unit. In the following weeks, he recaptured Berdiansk and Andriivka from the Bolsheviks. He defeated several Red divisions before a standstill with the remaining divisions.

Makhno hoped that defeating a few Red divisions would stop the attacks. But he found himself surrounded by many more soldiers. He decided to split his group into smaller units and send them in different directions. He took his own 2,000-strong group north, traveling 80 kilometers each day. He stopped a Bolshevik armored train. Then he pushed deep into other provinces, with Red divisions chasing him.

Surrounded and constantly pursued, Makhno's group could only move slowly under heavy fire. Makhno led his group to the border, then suddenly turned back across the Dnieper river. Heading north, they finally managed to escape the chasing Cossacks in late January 1921. By this point, he had traveled over 1,500 kilometers. He had lost most of his equipment and half of his group. But he was in a position to attack the Red Army again. After a rebellion broke out elsewhere, Makhno sent some of his groups to different regions to start uprisings. He himself stayed near the Dnieper River. At this time, Makhno was wounded in the foot. He had to be carried, but still led his group from the front. After crossing back, he split his group again. He sent one to stir up revolt near the Sea of Azov. Makhno's own group of 1,500 cavalry and two infantry regiments continued, taking equipment from the Red units they defeated. During one fight, Makhno was wounded in the stomach and lost consciousness. He had to be moved. When he woke up, he again divided his forces. He sent them in all directions, leaving himself with only his small guard.

Makhno could not leave the front to heal his injuries. His group was repeatedly attacked by the Red Army. In one fight, some of his fighters sacrificed themselves to help Makhno escape. Towards the end of May, Makhno tried to organize a large attack to take the Ukrainian Bolshevik capital of Kharkiv. He gathered thousands of fighters. But he had to call it off because of strong Red defenses. The Red Army decided to focus on Makhno's small group of 200. They sent a motorized unit to chase them. Makhno ambushed an armored car, took it, and drove it until it ran out of fuel. The chase lasted five days and covered 520 kilometers. It caused heavy losses to Makhno's group and almost ran them out of ammunition. Finally, they managed to escape the armored unit.

Life in Exile

Red Army commander Mikhail Frunze demanded the "final end" of the Makhnovist movement in July 1921. Makhno continued to lead raids despite several injuries. By August, these injuries convinced him to seek medical care abroad. He left Viktor Bilash in command of the army. Makhno, his wife Halyna Kuzmenko, and about 100 loyal followers headed for the Polish border. Red Army attacks followed them. Makhno was shot in the neck, and some of his old friends died in battle in late August. When a scout was captured by the Reds, Makhno changed direction towards Romania. After crossing the Dniester river, Romanian border guards disarmed and held Makhno's group. Makhno and his wife were later released and allowed to stay in Bucharest under police watch while Makhno recovered.

In Eastern Europe

Bolshevik leaders demanded Makhno be sent back to them. But the Romanian government refused. The two countries had no agreement for sending people back, and Romania had ended the death penalty. So, Romania asked for a promise that Makhno would not be sentenced to death. Makhno met with exiled Ukrainian nationalists. Makhno called for an alliance between his group and the nationalists. He believed they could start another uprising in Ukraine. But nothing came of these talks.

With Romania still dealing with the demands, Makhno decided to go to Poland. He was caught at the border and sent to a Polish camp in April 1922. Makhno then tried to get permission to move to Czechoslovakia or Germany, but Poland refused. The Bolshevik government sent a secret agent to trick Makhno. They wanted to involve him in a plan to start a rebellion in another region. This would force Poland to send him back. Makhno and his wife were formally accused by Polish authorities. They were held for over a year. Halyna gave birth to their daughter in October while in prison. In prison, Makhno wrote his first memories. He also sent letters to exiled Cossacks and the Ukrainian Communist Party. He started learning German and Esperanto. His tuberculosis returned due to the prison conditions.

Makhno received help from anarchists in Europe. Anarchists in Poland and Bulgaria even threatened action if Makhno was sent back. At their five-day trial in November 1923, Makhno and Halyna were found not guilty. They were given permission to live in Poznań. The next month, he and his family moved to Toruń. He was closely watched by police and arrested several times after Vladimir Lenin's death.

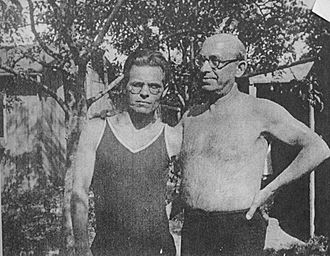

In July 1924, Makhno and his family were allowed to move to the Free City of Danzig. There, Makhno was quickly arrested for visa problems. While held, he became sick with tuberculosis again and was moved to a prison hospital. Makhno's anarchist friends helped him escape the hospital. After hiding, he secretly left for Berlin. With Volin helping him speak, Makhno met other anarchists living in the city. He finally moved to Paris in April 1925.

Life in Paris

When he arrived in Paris in April 1925, Makhno felt like he was "amongst foreign people and political enemies." He was reunited with his wife and daughter. French anarchists helped the family with housing and healthcare. Makhno found work at a foundry and a factory. But he had to leave both jobs due to his health. A bullet wound in his right ankle was very serious. His healthcare was managed by Lucile Pelletier, who said his body was "covered in scars." She advised his family to move out to avoid getting tuberculosis. Between his illness, homesickness, and a strong language barrier, Makhno became very sad. According to Alexander Berkman, Makhno disliked living in a big city. He dreamed of returning to Ukraine to "fight again for freedom and fairness."

Makhno started writing his Memoirs, but they didn't sell well. He also worked with exiled Russian anarchists to create a journal called Delo Truda (The Cause of Labor). Makhno published an article in each issue for three years. The editor criticized Makhno's writing, which upset Makhno. This made him dislike those anarchists he saw as "thinkers who didn't act." The ideas in the journal led to the Organizational Platform of the Libertarian Communists. This called for anarchists to organize more strongly, based on their experiences in Ukraine. The Platform was criticized by some who thought it made anarchism too much like Bolshevism. A meeting in March 1927 to discuss the Platform brought anarchists from many countries. When police raided the meeting, Makhno was arrested and threatened with being sent away. But he was defended by others, who helped him stay in France.

During this time, he often met anarchist friends in cafes. They would talk about the "good old days" in Ukraine. One time, he celebrated when his old rival Leon Trotsky lost power. He hoped Joseph Stalin would soon follow. In June 1926, Makhno met a Ukrainian Jewish anarchist named Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard became upset when he saw Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura. Schwarzbard told Makhno he planned to harm Petliura. He wanted revenge for attacks on Jewish communities in Ukraine, which had killed some of his family. Makhno tried to talk him out of it. But the act was carried out anyway. Schwarzbard's later trial showed much evidence of the attacks in Ukraine, which helped clear Schwarzbard.

Around this time, rumors spread about Makhno's own views on Jewish people. This led to public discussions. Some stories claimed Makhno was against Jewish people. Makhno strongly denied this. He defended himself by speaking about the attacks in Ukraine. In an article, he asked for proof of such views among his followers. At a debate in June 1927, Makhno said he had protected Ukrainian Jews. This was supported by Russian and Ukrainian Jews who were there. In Ukraine, Makhno had condemned and punished cases of harm against Jewish communities. He even ordered the removal of those who participated in attacks and gave weapons to Jewish communities for their protection. Historians and some of Makhno's biographers have also said that claims of him being against Jewish people were not true.

By this time, Makhno was suffering from physical and mental illness. His relationships with other Ukrainian exiles became difficult. His wife grew unhappy with him, and they separated several times. Halyna even tried to get permission to return to Soviet Ukraine. Makhno argued with his editor over his memoirs. He also had a serious personal and political conflict with another anarchist, which lasted until their deaths. As rumors spread about Makhno, he became very defensive against any criticism. He published strong denials about various claims, from being against Jewish people to whether his group used a certain flag.

Feeling distant from many Russian and French anarchists in Paris, Makhno turned his attention to Spain. After Spanish anarchists were released from prison, Makhno met with Francisco Ascaso and Buenaventura Durruti in July 1927. The Spaniards admired Makhno. Makhno felt hopeful about the Spanish anarchist movement and predicted a coming revolution in Spain. He was especially impressed by the Spanish working classes and the strong organization of Spanish anarchists. He said that if a revolution happened in Spain before he died, he would join the fight.

Because of threats of being sent away, he mostly focused on writing. He could no longer attend meetings or actively organize. In great pain, increasingly alone, and struggling financially, Makhno took odd jobs as a decorator and shoemaker. He was also supported by his wife's income as a cleaner. In April 1929, French anarchists set up a "Makhno Solidarity Committee" to raise money. Much of the money came from Spanish anarchists, who greatly admired Makhno. The fundraising helped Makhno's family get a small weekly allowance. Makhno spent most of this money on his daughter, neglecting his own health. This made his health worse. His disagreements with other anarchists grew. In July 1930, his allowance was stopped. Other fundraising attempts were not successful.

Around this time, Makhno learned that Peter Arshinov had gone to the Soviet Union. This made him feel even more alone. Makhno spent his last years writing criticisms of the Bolsheviks. He encouraged other anarchists to learn from the mistakes of the Ukrainian experience. His last article, for an old friend, was not sent because Makhno couldn't afford the postage. As he suffered from poor nutrition, Makhno's tuberculosis worsened. He was hospitalized on March 16, 1934. Operations did not help. Makhno died in the early hours of July 25, 1934. He was cremated three days later. Five hundred people attended his funeral at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Family Life

While in prison in the 1910s, Makhno received "warm letters" from Nastia Vasetskaia, a young peasant woman from Huliaipole. After he returned home in 1917, they became a couple. They lived together on a shared farm, where Makhno also worked. However, his busy revolutionary work left him "little time for personal affairs." Vasetskaia later had to leave Huliaipole after being threatened, taking their child with her. After Makhno himself had to leave due to an invasion in early 1918, he managed to meet Vasetskaia again. He found her a place to stay on a nearby farm. Makhno soon left her to continue his travels. They never saw each other again. Their baby passed away young. After hearing a rumor that Makhno had also died, Vasetskaia found another partner.

After Makhno's group took Huliaipole in late 1918, Makhno met a local schoolteacher named Halyna Kuzmenko. She became his wife and an important figure in his movement. When Makhno's movement was defeated, the couple went to Romania and then to Poland. Halyna gave birth to their daughter Elena while she and Makhno were in prison. The family eventually settled in Paris. But they had to live separately for some time because of Makhno's worsening tuberculosis.

Makhno's wife and daughter were later sent to Nazi Germany for forced labor during World War II. After the war, Soviet authorities arrested them. They were taken to Kyiv for a trial in 1946. Halyna was sentenced to eight years of hard labor, and Elena to five years. After the death of Joseph Stalin, they were reunited. They spent the rest of their lives there. Halyna passed away in 1978, and Elena in 1993. Makhno's relatives in Huliaipole faced difficulties from Ukrainian authorities until the end of the Soviet Union.

Makhno's Lasting Impact

The Ukrainian anarchist movement continued after Makhno left in 1921. Groups of Makhnovist fighters operated secretly throughout the 1920s. Some even continued to fight during World War II. Although the Soviets eventually stopped the Ukrainian anarchist movement, an anarchist underground continued in the 1970s and after the fall of communism. Various anarchist groups are inspired by Makhno. For example, a group called the Revolutionary Confederation of Anarcho-Syndicalists—"Nestor Makhno" was founded in 1994. Anti-fascist fighters have also claimed Makhno's legacy. "Neo-Makhnovist" ideas appeared among anarchists who took part in the Revolution of Dignity.

Makhno is a local hero in his hometown of Huliaipole. A statue of him stands in the main town square. The Huliaipole Local History Museum has an exhibition about Makhno. In the late 2010s, the Huliaipole City Council planned to ask for Makhno's ashes to be returned from France. This was part of a plan to attract tourists to the city. Since the Soviet Union ended, some far-right groups in Ukraine have tried to claim Makhno as a Ukrainian nationalist. They try to downplay his anarchist beliefs.

Many Soviet and Russian films showed Makhno, often in a negative way. He was an antagonist in the 1923 film Red Devils. He was played by an actor who later used "Makhno" as a fake name for criminal activity. Another actor played Makhno in the 1942 film Alexander Parkhomenko. In this film, he famously sang a traditional song. Other films and TV series also showed Makhno negatively.

The 2005 TV series Nine Lives of Nestor Makhno was a Russian show about his life. The actor who played Makhno received high praise. The series was noted for showing Makhno in a more positive light. A French documentary about Makhno was made in 1995.

Makhno has also been mentioned in popular culture. He appeared in a novel and was the subject of a song by a Russian rock band. A US politician wrote a song about him. His name was also used as a nickname by a leader of a movement in San Francisco.

After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Nestor Makhno's legacy was again taken up by Ukrainian anti-authoritarians. They joined the Territorial Defense Forces. Symbols of Makhno's movement have appeared in propaganda and on flags. The Ukrainian Armed Forces also named their defense forces in the battle of Huliaipole "Makhno's bow." A museum exhibition on Makhno was damaged during shelling. His statue in the town center is covered with sandbags to protect it.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Néstor Majnó para niños

In Spanish: Néstor Majnó para niños

- Alexander Antonov

- Rummu Jüri

- Svyryd Kotsur

- Ricardo Flores Magón

- Stepan Petrichenko

- Danylo Terpylo

- Emiliano Zapata

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |