Volin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Volin

|

|

|---|---|

|

Волин

|

|

|

|

| Chairman of the Military Revolutionary Council of the Makhnovshchina | |

| In office 1 September 1919 – 31 January 1920 |

|

| Preceded by | Nestor Makhno |

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Popov |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum

23 August [O.S. 11 August] 1882 Voronezh, Russian Empire |

| Died | 18 September 1945 (aged 63) Paris, French Republic |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Political party | Socialist Revolutionary (1904–1911) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Education | Saint Petersburg State University |

| Occupation |

|

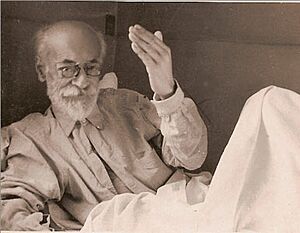

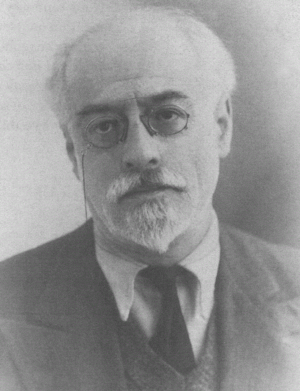

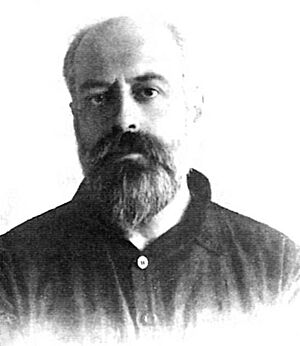

Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum (23 August [O.S. 11 August] 1882 – 18 September 1945) was a Russian thinker and writer. He was better known by his pen name, Volin.

Volin was an anarchist, meaning he believed in a society without a government or rulers. He became involved in politics during the 1905 Russian Revolution. Because of his political actions, he was forced to leave Russia. During this time, he became interested in anarcho-syndicalism, a type of anarchism focused on workers' unions.

He returned to Russia in 1917 during the February Revolution. He promoted his ideas in the capital city, Petrograd. After the October Revolution, which brought the Bolsheviks to power, he moved to Ukraine. There, he became a key leader in the Makhnovshchina, a large anarchist movement.

Volin developed an idea called synthesis anarchism. This idea encouraged different types of anarchists to work together. He also helped shape the ideas of Ukrainian anarchism as a leader of the Nabat group. He even chaired the Military Revolutionary Council during the civil war.

After the Bolsheviks stopped the anarchist movements in Russia and Ukraine, Volin had to leave Russia again. He went to Paris, France. There, he wrote many articles and books in different languages. He lived his last years in poverty, trying to avoid the Nazis and the French government because he was Jewish and an anarchist. He died from tuberculosis shortly after France was freed from Nazi control.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Volin was born Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum on August 23, 1882. He came from an educated Jewish family in Voronezh, a city in the Russian Empire. His parents were both doctors.

They hired tutors from Western countries for Volin and his brother, Boris. This meant they learned French and German, as well as Russian. After finishing school in Voronezh, Volin moved to Saint Petersburg. He studied law at Saint Petersburg State University.

Political Beginnings

By 1901, Volin started getting involved in the growing workers' movement in Saint Petersburg. In 1904, he left university to become a full-time activist. He joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

Volin mostly taught workers, helped set up a library, and organized study groups. He was part of the 1905 Russian Revolution from the very beginning. He saw the events of Bloody Sunday. He also helped create the Saint Petersburg Soviet, a council for workers.

He was arrested for his role in an uprising at Kronstadt and briefly jailed. After the revolution was put down, he was arrested again in 1907. He was sent to Siberia, a cold region in Russia. However, he managed to escape and fled to France.

Exile and Return

In Paris, Volin met many anarchists, including Sébastien Faure from France and Apollon Karelin from Russia. By 1911, he decided to become an anarchist. He left the Socialist Revolutionary Party and joined Karelin's Brotherhood of Free Communists.

When World War I started, Volin immediately joined the anti-war movement. This made the French authorities notice him. He avoided being caught and escaped to the United States in 1915. In New York City, he joined the Union of Russian Workers. This was a group of Russian-American anarcho-syndicalists.

He became an editor for their newspaper, Golos Truda (Voice of Labor). In late 1916, he went on a speaking tour across North America. After the February Revolution in Russia, Volin returned home in July 1917. He and his colleagues restarted their newspaper in Petrograd. They spread anarcho-syndicalist ideas directly to the workers there.

Revolutionary Activities

Volin quickly became a leading voice for anarcho-syndicalism during the 1917 Revolution. He often spoke to workers in Petrograd, calling for them to control their workplaces. As editor of Golos Truda, he helped the newspaper reach 25,000 readers.

After the October Revolution, Volin openly criticized the Bolsheviks. He warned that they would become too powerful and take control from the workers' councils (soviets). He especially disliked the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. He felt it meant the Bolsheviks were giving up on a worldwide revolution. He wanted people to keep fighting against the Central Powers. So, he decided to move to Ukraine, which was occupied by German and Austro-Hungarian forces.

After visiting family in Voronezh, Volin spent a few months organizing schools in Bobrov. Then, he moved to Kharkiv. There, he helped create the Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organisations. In November 1918, at their first meeting, he wrote a statement of beliefs. This statement was meant to unite different types of anarchists: anarcho-communists, individualists, and anarcho-syndicalists.

Volin's idea was called synthesis anarchism. It encouraged anarchists with different views to work together. Some of his old comrades, like Grigorii Maksimov, thought this idea wouldn't work. But Volin kept promoting his ideas through the Nabat. The Nabat grew, with branches across Ukraine, a youth group, and a publishing house.

By mid-1919, the Bolsheviks noticed the Nabat. They closed its meeting places and newspaper. Volin then moved the Nabat's main office to Huliaipole. There, it became a key part of the Makhnovshchina. This was a large anarchist movement led by Nestor Makhno's Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine.

Volin joined the movement's Cultural-Educational Commission. He edited their writings and organized their regional meetings. He even became the chairman of the Military Revolutionary Council (RVS), which was the movement's main leadership group. As chairman, Volin disagreed with the army's leaders about the harsh violence used by their secret police. He also edited the movement's Draft Declaration. This document suggested creating free soviets as a way to move towards a communist society.

In December 1919, Volin went to Kryvyi Rih to fight against the spread of Ukrainian nationalism. But he got typhus and had to stop to recover in a village. On January 14, 1920, he was arrested while sick in bed by the 14th Army. He was handed over to the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. They had orders from Leon Trotsky to execute him.

Russian-American anarchists like Alexander Berkman tried to get his sentence changed. But Nikolay Krestinsky, a former colleague of Volin, refused. Other Russian libertarians, including the Bolshevik Victor Serge, eventually helped. Volin was moved to Butyrka prison in Moscow, and his death sentence was changed. He was finally released in October 1920. This was part of a deal between the Bolsheviks and the Makhnovists called the Starobilsk agreement. He was even offered a job as a government official in Ukraine, but he said no.

In November, he quickly visited Dmitrov. There, he paid his respects to a dying Peter Kropotkin, who was feeling sad about the revolution's future. Volin then returned to Kharkiv. He started planning an All-Russian Congress of Anarchists for December 25. He also led talks with the government about a tricky part of the Starobilsk agreement. This part would have given the Makhnovshchina more freedom.

After the Soviet army won a battle in Crimea, Volin and other Nabat members were arrested again. They were imprisoned in Moscow. In July 1921, after a French union leader visited them, Volin and other anarchist prisoners went on a hunger strike. They wanted to get the attention of other visiting union delegates. After these delegates protested to Vladimir Lenin, the prisoners were released. They were then sent out of Russia in January 1922.

Life in Exile

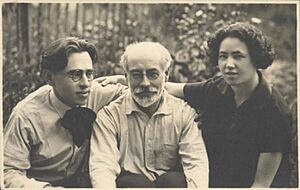

Volin and his family went to Berlin, Germany. German anarchists like Rudolf Rocker helped them. They gave them a small attic to live in. In Berlin, Volin worked with Alexander Berkman to help anarchist prisoners and exiles. He even helped Nestor Makhno escape from Poland to Berlin.

Volin also published a weekly newspaper called The Anarchist Herald. He translated a book about the Makhnovist movement and shared proof of how Russian anarchists were being treated unfairly. In 1924, his old friend Sébastien Faure invited him back to Paris. They worked together on Faure's Anarchist Encyclopedia.

Volin became a key writer for the encyclopedia. He also wrote for many anarchist newspapers in different languages. These included French, German, English, Russian, and Yiddish papers. Around this time, he also started writing his own history of the Russian Revolution.

In 1927, Volin was part of a big debate about something called the Platform. This caused a disagreement among Russian anarchists living in exile. Volin strongly criticized the Platform. He said it went against the anarchist idea of decentralisation (spreading power out). He felt it tried to create an anarchist political party.

This disagreement led to a difficult falling out with Nestor Makhno. Makhno felt Volin was too focused on intellectual ideas. However, they made up before Makhno died in 1934, thanks to Makhno's wife. Volin then took on the job of editing and publishing Makhno's memories.

Besides criticizing platformism, Volin also spoke out against Bolshevism. He called it "red fascism" and compared the actions of Joseph Stalin to those of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. He criticized anarchists who had wanted to work with the Bolshevik government.

Volin tried to keep teaching about anarchism for free. But he also needed money for his family. So, he took several jobs in publishing. He worked on a Russian translation of a play called Lazarus Laughed. After the Spanish Revolution of 1936, he briefly worked for a Spanish anarchist newspaper in French. But he quit when the organization joined the government.

Volin lived in poverty for many years. Then, André Prudhommeaux gave him a job on the board of his newspaper Terre Libre. Volin contributed to it from Nîmes.

In 1940, while living in poverty in Marseilles, he finished his book The Unknown Revolution. This book was a history of the Russian Revolution. When Nazi Germany invaded France and set up the French State, Volin had to hide. This was because he was Jewish and an anarchist.

His friends Senya Fleshin and Mollie Steimer tried to convince him to escape to Mexico with them. But he decided to stay in France. He believed there would be a revolution after World War II. However, by the time France was freed, he had caught tuberculosis. Volin died in a hospital in Paris on September 18, 1945. His ashes were buried in a special spot at the Père Lachaise Cemetery, close to where his friend Nestor Makhno rests.

In his tribute to Volin, written a month after his death, Victor Serge called him "one of the most remarkable figures of Russian anarchism." He described Volin as a man of great honesty and clear thinking. Serge hoped that the future would remember this brave revolutionary. He said Volin always showed "real moral greatness," whether in prison, in poverty, on the battlefield, or in an office.

Works