Anton Denikin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anton Denikin

|

|

|---|---|

| Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин | |

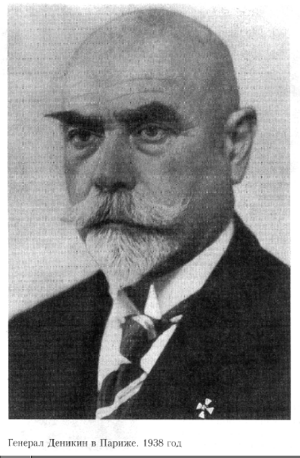

Denikin in 1938

|

|

| Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of South Russia | |

| In office 8 January 1919 – 4 April 1920 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Pyotr Wrangel |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Anton Ivanovich Denikin

16 December 1872 Włocławek, Warsaw Governorate, Vistula Land, Russian Empire |

| Died | 7 August 1947 (aged 74) Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States |

| Spouse | Xenia Vasilievna Chizh |

| Relations | Marina Denikina (daughter) |

| Awards | See below |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | (1890–1917) (1917–1920) |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1890–1920 |

| Rank | Lieutenant general |

| Battles/wars | Russo-Japanese War World War I Russian Civil War |

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (Russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин) was a Russian Lieutenant General. He was born on December 16, 1872, and died on August 7, 1947. He served in the Imperial Russian Army and later became an important leader during the Russian Civil War.

Denikin was a key figure in the White movement, which fought against the Bolsheviks (the Red Army). His main goal was to keep Russia united. His famous saying was “Russia - One and Indivisible.”

Contents

Early Life and Military Training

Anton Denikin was born in 1872 in a village called Szpetal Dolny. This village was part of the Russian Empire, in what is now Poland. His father, Ivan Denikin, was born a serf, which meant he was tied to the land.

Ivan Denikin joined the army and served for 25 years. He became an officer before he retired. Anton's mother was a Polish seamstress named Elżbieta Wrzesińska. Anton was their only child. He grew up speaking both Russian and Polish. His father’s strong love for Russia and the Russian Orthodox Church inspired Anton to join the army.

The Denikin family was quite poor. They lived on his father's small pension. After his father died in 1885, their money problems got worse. Anton started tutoring younger students to help his family. In 1890, he enrolled in the Kiev Junker School, a military college. He graduated from there in 1892. After graduating, he joined an artillery brigade and served for three years.

In 1895, Denikin tried to get into the General Staff Academy. He didn't do well enough in his first year. He tried again and did much better, finishing high in his class. However, a new grading system meant he wasn't offered a staff job. He protested this decision to a very high authority. He was offered a deal to get back into the school, but he refused, feeling insulted.

Denikin first saw real combat during the 1905 Russo-Japanese War. In 1905, he was promoted to colonel. By 1910, he was in charge of the 17th infantry regiment. Just before World War I began, Denikin became a major-general.

Fighting in World War I

When World War I started in August 1914, Denikin was a chief of staff in the Kiev Military District. He first worked as a quartermaster for General Aleksei Brusilov. But Denikin preferred to be on the front lines, fighting. He asked to be moved to a fighting unit. He was transferred to the 4th Rifle Brigade, which became the 4th Rifle Division in 1915.

In October 1916, he was given command of the Russian 8th Army Corps. He led troops in Romania. After the February Revolution in 1917, which overthrew Tsar Nicholas II, Denikin became a chief of staff for several top generals. He also commanded the Southwestern Front for a short time. He supported General Lavr Kornilov's attempt to take control in September 1917. Because of this, Denikin was arrested and put in prison with Kornilov.

The Russian Civil War

After the October Revolution, Denikin and Kornilov escaped to Novocherkassk. There, they and other officers who supported the Tsar formed the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army. General Alekseev first led this army. In April 1918, Kornilov was killed, and Denikin took command of the Volunteer Army. This happened partly because General Sergey Markov supported him.

Kornilov had tried to capture the city of Ekaterinodar, but it failed. Denikin's army had to retreat to avoid being destroyed. This retreat became known as the Ice March. Some people wanted Grand Duke Nicholas to be the overall leader, but Denikin did not want to share power. From June to November 1918, Denikin led a very successful campaign called the Second Kuban Campaign. This gave him control of a large area between the Black and Caspian Seas.

In the summer of 1919, Denikin led the southern White forces in their final push to capture Moscow. For a while, it looked like the White Army might win. However, Leon Trotsky, who led the Red Army, made a deal with Nestor Makhno's anarchist army. Makhno's army attacked Denikin's supply lines, forcing the White Army to retreat. Denikin's army was badly defeated at Orel in October 1919. This was about 360 kilometers south of Moscow. After this, the White forces in southern Russia kept retreating. They eventually reached the Crimea in March 1920.

On January 4, 1920, Admiral Alexander Kolchak, who was facing defeat, named Denikin as his successor. Kolchak was the Supreme Ruler of Russia. However, Denikin did not accept this role. Meanwhile, the Soviet government broke its agreement with Makhno and attacked his anarchist forces. After many battles, the larger and better-equipped Red Army defeated Makhno's army.

Denikin did not recognize the independence of Azerbaijan and Georgia. But he had good relations with Armenia. He recognized their independence and sent them ammunition during some conflicts.

Challenges and Criticisms

During the Russian Civil War, there was a lot of violence against Jewish communities. Denikin's army was accused of being involved in some of these attacks. They were also known for spreading propaganda that linked Jewish people with communism.

In areas his army controlled, there were reports of violence and looting. For example, in the town of Maykop, over 4,000 people were killed by forces under General Pokrovsky, who was part of Denikin's army. In Fastov, Denikin's army was accused of killing over 1,500 Jewish people.

Denikin himself was a religious man and loyal to the Russian Orthodox Church. He did not openly criticize the attacks on Jewish people until late 1919. He believed that many people had reasons to dislike Jewish people. He also wanted to avoid issues that might divide his officers. Many of his officers were strongly against Jewish people. They allowed these violent acts, which caused terror among Jewish communities. This also helped them gain favor with some Ukrainian people in 1919.

Western countries that supported the White Army were worried about the widespread anti-Jewish feelings among the White officers. This was especially true because the Bolsheviks tried to officially ban acts against Jewish people.

Life After the War

Facing growing criticism and feeling very tired, Denikin resigned in April 1920. General Baron Pyotr Wrangel took over from him. Denikin left the Crimea by ship, first going to Istanbul, then to London. He stayed in England for a few months, then moved to Belgium, and later to Hungary.

From 1926, Denikin lived in France. He was still strongly against Russia's Communist government. However, he chose to live a quiet life, away from political arguments among exiles. He spent most of his time writing and giving lectures. The Soviets tried to kidnap him, but they were not successful. They did manage to kidnap other exile generals later on.

Denikin was a talented writer. Before World War I, he wrote several pieces criticizing problems in the Russian Army. His many writings after the Russian Civil War, which he wrote while in exile, are known for being thoughtful and honest. Since he enjoyed writing and it was his main source of income, Denikin saw himself as a full-time writer. He became good friends with several Russian writers who were also living in exile. These included Ivan Bunin, who won a Nobel Prize.

Even though some Russian exiles respected him, Denikin was not liked by exiles from either the far right or the far left. When France fell in 1940 during World War II, Denikin left Paris to avoid being captured by the Germans. He was eventually caught, but he refused to help the Nazis with their anti-Soviet propaganda. The Germans did not push him and allowed him to stay in the countryside.

At the end of World War II, Denikin knew what would likely happen to Soviet prisoners of war. He tried to convince the Western Allies not to force these prisoners to return to Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union. He was mostly unsuccessful in this effort.

From 1945 until his death in 1947, Denikin lived in New York City, United States. On August 7, 1947, he died of a heart attack at age 74. This happened while he was on vacation near Ann Arbor, Michigan.

General Denikin was buried with military honors in Detroit. His remains were later moved to St. Vladimir's Cemetery in Jackson, New Jersey. His wife, Xenia Vasilievna Chizh, was buried near Paris.

On October 3, 2005, Denikin's remains were moved from the United States to Moscow. This was done according to the wishes of his daughter, Marina Denikina, and with permission from Russian President Vladimir Putin. He was buried at the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow, next to Ivan Ilyin.

Vladimir Putin mentioned Denikin's diary during a visit to the Donskoy Monastery in 2009. Putin said the diary was important for understanding the relationship between "Great and little Russia, Ukraine." He highlighted parts where Denikin described Ukraine as an inseparable part of Russia. Putin suggested that Denikin’s diary was worth reading.

Honours

Order of St. Stanislaus, 2nd degree with Swords (1904); 3rd degree (1902)

Order of St. Anne, 2nd degree with Swords (1905); 3rd degree with swords and bows (1904)

Order of St. Anne, 2nd degree with Swords (1905); 3rd degree with swords and bows (1904) Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd degree (18 April 1914); 4th degree (6 December 1909)

Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd degree (18 April 1914); 4th degree (6 December 1909) Order of St. George, 3rd degree (3 November 1915); 4th degree (24 April 1915)

Order of St. George, 3rd degree (3 November 1915); 4th degree (24 April 1915)- Golden Sword of St. George (10 November 1915)

- Golden Sword of St. George, decorated with diamonds, with the inscription "For the double release of Lutsk (22 September 1916)

Order of Michael the Brave, 3rd degree, 1917 (Romania)

Order of Michael the Brave, 3rd degree, 1917 (Romania) Croix de Guerre, 1914-1918, 1917 (France)

Croix de Guerre, 1914-1918, 1917 (France) Sign of the 1st Kuban Ice Campaign, 1918

Sign of the 1st Kuban Ice Campaign, 1918 Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, 1919 (UK)

Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath, 1919 (UK) Order of the White Eagle (Serbia)

Order of the White Eagle (Serbia)

Denikin's Works

Denikin wrote several books, including:

- Russian Turmoil. Memoirs: Military, Social & Political. Hutchinson. London. 1922. (only volume 1 of 5 has been published in English.)

- Republished: Hyperion Press. 1973. ISBN: 978-0-88355-100-4

- The White Army. Translated by Catherine Zvegintsov. Jonathan Cape, 1930.

- The Career of a Tsarist Officer: Memoirs, 1872-1916. Translated by Margaret Patoski. University of Minnesota Press. 1975.

See Also

In Spanish: Antón Denikin para niños

In Spanish: Antón Denikin para niños