Errico Malatesta facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Errico Malatesta

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 4 December 1853 Santa Maria Capua Vetere, Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

|

| Died | 22 July 1932 (aged 78) |

| Occupation | Revolutionary, activist, writer |

|

Philosophy career |

|

| School | Anarcho-communism |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

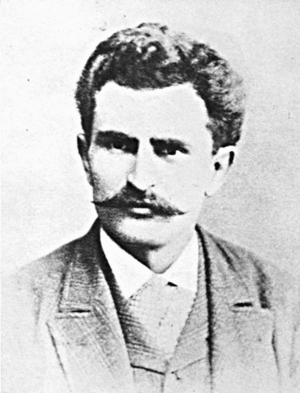

Errico Malatesta (born December 4, 1853 – died July 22, 1932) was an Italian anarchist writer and activist. He believed in a society without rulers or strict governments, where people could live freely and cooperate. He spent much of his life traveling, writing, and being imprisoned or sent away from different countries because of his strong beliefs. He edited many newspapers that shared his ideas and worked to inspire social change.

Contents

Errico Malatesta's Life

Early Adventures

Errico Malatesta was born on December 4, 1853, in Santa Maria Capua Vetere, Italy. His family were landowners. When he was just 14, he was arrested for writing a strong letter to the king, Victor Emmanuel II. This was his first arrest, but it would not be his last.

In April 1877, Malatesta and about 30 other people started a small uprising in the Benevento province. They took over two villages, Letino and Gallo, without a fight. The group burned tax records and announced the end of the king's rule. People in the villages were excited by this.

However, government troops soon arrested them. Malatesta and the others were held for 16 months before being found innocent. After this, the police watched Malatesta closely. He was forced to leave Italy in late 1878, beginning a long period of living in exile.

Years of Travel and Exile

Malatesta first went to Egypt but was quickly sent away. He tried to enter other countries but was refused. Finally, he landed in Marseille, France, and then went to Geneva, Switzerland. Geneva was a center for anarchists at the time.

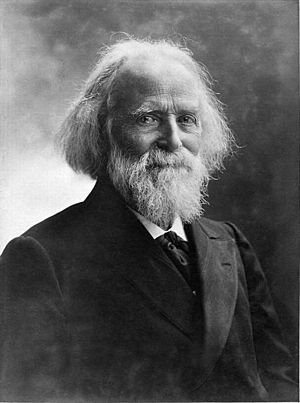

In Geneva, he became friends with famous anarchists like Élisée Reclus and Peter Kropotkin. He even helped Kropotkin with his newspaper, La Révolte. But his time in Switzerland was short, and he was soon expelled again. He traveled to Romania and then Paris, where he worked as a mechanic.

In 1881, Malatesta moved to London, England. He would live there off and on for the next 40 years. He worked as a mechanic and continued his activism. He attended an Anarchist Congress in London in July 1881. At this meeting, anarchists agreed that "propaganda by the deed" (actions to inspire change) was important for social revolution.

In 1882, Malatesta tried to help fight against the British in the Anglo-Egyptian War. He went to Egypt with a small group, but they were captured by British forces before they could fight. He secretly returned to Italy the next year.

In Florence, Italy, he started a weekly anarchist newspaper called La Questione Sociale (The Social Question). His popular booklet, Fra contadini (Among Farmers), first appeared in this paper. In 1884, he went back to Naples to help people suffering from a cholera outbreak. To avoid prison, he fled Italy again, this time to South America.

He lived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from 1885 to 1889. There, he started publishing La Questione Sociale again. He helped spread anarchist ideas among Italian immigrants and was involved in starting the first strong workers' union in Argentina. His ideas influenced workers' movements there for many years.

After returning to Europe in 1889, Malatesta published another newspaper called L'Associazione in Nice, France. But he was soon forced to flee to London once more.

Facing Arrest in Italy

The late 1890s were a difficult time in Italy, with bad harvests and rising prices. Workers went on strike, and there was a lot of social unrest. Malatesta felt he had to be there, so he returned to Ancona, Italy, in 1898. He joined the growing anarchist movement among the dockworkers.

Malatesta was quickly seen as a leader during street fights with the police and was arrested. This meant he could not take part in the big protests of 1898 and 1899. From jail, Malatesta strongly argued against anarchists participating in elections, even when other anarchist leaders thought it might be helpful.

He was found guilty of "seditious association" (trying to cause rebellion) and sent to prison on the island of Lampedusa. But in May 1899, he managed to escape with help from friends around the world. He traveled through Malta and Gibraltar to get back to London.

In the following years, Malatesta visited the United States. He gave talks to Italian and Spanish immigrant communities who were interested in anarchism. Back in London, the police watched him closely. They saw anarchists as a threat, especially after an Italian anarchist assassinated King Umberto I of Italy in 1900.

Final Years in London and Italy

While living in London, Malatesta made secret trips to France, Switzerland, and Italy. He also gave lectures in Spain. During this time, he wrote important pamphlets, including L'Anarchia (Anarchy).

He also took part in the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam in 1907. Here, he debated with Pierre Monatte about the connection between anarchism and syndicalism (trade unionism). Monatte believed that trade unions could lead to social revolution, but Malatesta thought that unions alone were not enough.

After World War I, Malatesta returned to Italy for the last time. In 1921, the Italian government imprisoned him again. He was released two months before the fascists, led by Benito Mussolini, came to power.

From 1924 to 1926, Malatesta published a journal called Pensiero e Volontà (Thought and Will). However, he was often bothered by the government, and his journal faced censorship. He spent his last years living a quieter life, working as an electrician. He had breathing problems for many years and died on July 22, 1932, from bronchial pneumonia.

Malatesta's Ideas

Errico Malatesta was a very important leader in the Italian anarchist movement. While other leaders changed their minds or left politics, Malatesta stayed true to his beliefs for 50 years. He believed in anarchism, which means a society without a government or rulers, where people are free and equal.

Malatesta wanted to unite anarchists and other anti-government socialists into a new group. He also believed that anarchists should encourage workers to rise up and always remind them of the revolutionary goals. He called his type of anarchism "anarchism without adjectives". This meant that different kinds of anarchists (like those who believed in collectivism or communism) should be tolerant of each other. He hoped that even Marxist socialists would allow anarchists freedom in a society after a revolution.

Views on Labor Unions

Malatesta had strong opinions about trade unions (groups of workers who join together to protect their rights). At the Amsterdam Conference in 1907, he argued that trade unions, by themselves, were often focused on small changes rather than a complete revolution. He thought they could even be conservative sometimes. For example, he pointed out that unions of skilled workers in the United States sometimes opposed unskilled workers to protect their own better positions.

Malatesta warned that if syndicalists (people who believe unions are the main way to revolution) only focused on making unions stronger, they might forget the bigger goal. Anarchists, he said, must always aim to overthrow capitalism and the state to create an anarchist society. They should not get stuck on just one method to achieve this.

Even though he had these concerns, Malatesta believed anarchists should still be active in trade unions. He thought unions were important for workers to organize and protect themselves under capitalism. They were also a way to reach more people with anarchist ideas. However, he felt that anarchists should not try to make unions completely anarchist. He also said that any anarchist who became a full-time, paid union official would stop being a true anarchist.

Selected Works

- Between Peasants: A Dialogue on Anarchy (1884)

- Anarchy (1891)

- At the Cafe: Conversations on Anarchism (1922)

See also

In Spanish: Errico Malatesta para niños

In Spanish: Errico Malatesta para niños