Jerry Fodor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jerry Fodor

|

|

|---|---|

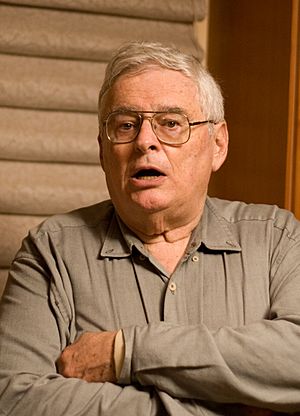

Fodor in 2007

|

|

| Born |

Jerry Alan Fodor

April 22, 1935 New York City, US

|

| Died | November 29, 2017 (aged 82) New York City, US

|

| Alma mater | Columbia University Princeton University |

| Awards | Jean Nicod Prize (1993) |

| Era | 20th-/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic |

| Institutions | Rutgers University |

| Thesis | The Uses of "Use": A Study in the Philosophy of Language (1960) |

| Doctoral advisor | Hilary Putnam |

| Other academic advisors | Sydney Morgenbesser |

|

Main interests

|

Philosophy of mind Philosophy of language Cognitive science Rationalism Cognitivism Functionalism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Modularity of mind Language of thought |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Jerry Alan Fodor (born April 22, 1935 – died November 29, 2017) was an American philosopher. He wrote many important books about how our minds work and how we think. His ideas helped create the theories of the modularity of mind and the language of thought.

Fodor believed that our mental states, like beliefs and desires, are connections between us and "mental pictures" or ideas. He thought these mental pictures could only be truly understood if we imagine a "language of thought" (LOT) inside our minds. This LOT, he argued, is a real thing coded in our brain, not just a helpful idea.

He also believed in something called functionalism. This means that thinking and other mental processes are like calculations. These calculations work on the rules (or syntax) of the mental pictures that make up the language of thought.

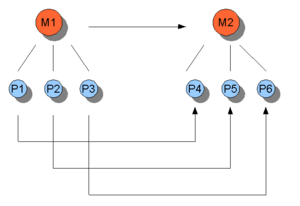

Fodor thought that big parts of our mind, like how we see and how we use language, are organized into "modules." Think of these modules as special "organs" in the mind. They work mostly on their own, separate from the "central processing" part of the mind. This central part handles more general thinking. Fodor suggested that these modules help our mental states connect to things in the real world.

Even though Fodor first disagreed that mental states are connected to the outside world, he later studied the philosophy of language a lot. He wanted to understand how our thoughts get their meaning. He also strongly disagreed with ideas that try to explain the mind by breaking it down into simpler parts. He argued that mental states can be created in many different physical ways. He also criticized Darwin's and neo-Darwinian theories of natural selection.

Contents

About Jerry Fodor's Life

Jerry Fodor was born in New York City on April 22, 1935. He went to Columbia University and then got his PhD in philosophy from Princeton University in 1960. His teacher there was Hilary Putnam.

From 1959 to 1986, Fodor taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He also taught at the City University of New York (CUNY) and Rutgers University. He retired in 2016. Besides philosophy, Fodor loved opera and often wrote articles about it for the London Review of Books.

Fodor was part of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He won many awards, including the first Jean Nicod Prize in 1993 for his work in philosophy of mind. He also gave important lectures at the University of Oxford.

He lived in Manhattan with his wife, Janet Dean Fodor, who was a linguist. They had two children. Jerry Fodor passed away at home on November 29, 2017.

How Our Minds Work: Fodor's Ideas

Jerry Fodor had some big ideas about how our minds work. He believed that our thoughts and beliefs are like special relationships between us and "mental representations." These are like internal symbols or sentences in our minds.

He thought that to really understand how we think, we need to imagine a "language of thought" (LOT) inside our brains. This isn't like English or Spanish, but a basic mental code. He argued that our mental processes are like a computer working with this code.

The Mind's Building Blocks: Modularity

Fodor believed that our minds are built with special "modules." Think of these as separate, specialized tools or programs in your brain. Each module handles a specific job, like seeing colors or understanding words.

These modules are mostly independent. For example, the part of your brain that processes what you see works separately from the part that understands language. This idea is called the modularity of the mind.

Fodor said these modules are "informationally encapsulated." This means they do their job without needing to know everything else you believe or know. For instance, when you see a stick in water that looks bent, your visual module still processes it as bent, even if you know it's actually straight.

Thinking Like a Computer: Functionalism

Fodor supported functionalism. This idea says that what matters about a mental state (like believing something) is its function or what it does, not what it's made of.

Imagine a computer program. It can run on a PC, a Mac, or even a smartphone. The program does the same thing, even though the machines are very different. Functionalism says our mental states are similar. A thought can happen in a human brain, an alien brain, or even a very advanced computer. The important part is the thought itself, not the specific "stuff" it's made from. This is called the principle of multiple realizability.

Jerry Fodor and Evolution

Jerry Fodor, along with Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, wrote a book called What Darwin Got Wrong (2010). In this book, they argued that Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, especially the modern version (neo-Darwinism), gives too much credit to the environment in shaping living things. They believed it didn't focus enough on internal factors.

This book caused a lot of discussion. Some scientists, like Jerry Coyne, strongly disagreed with it, calling it a "misguided critique." However, others, like philosopher Mary Midgley, praised it for challenging common ideas about evolution.

Challenges to Fodor's Ideas

Many philosophers have questioned Fodor's theories.

Is There a Language of Thought?

One big question was about his "language of thought" (LOT). Some critics, like Simon Blackburn, asked: If we need a LOT to learn natural languages (like English), then how do we learn the LOT itself? Do we need an even more basic language to learn the LOT? This could go on forever! Fodor's answer was that the LOT is special because it's not learned; it's innate, meaning we are born with it.

Another philosopher, Daniel Dennett, argued that we don't always need explicit mental representations to explain behavior. For example, when you play chess against a computer, you might say, "The computer thinks it should move its queen." But you don't really believe the computer has feelings or beliefs like a human. Dennett suggested that many of our automatic actions don't need a "language of thought" to explain them.

Are Concepts Innate?

Fodor also believed that many of our basic concepts, like "EFFECT" or "ISLAND," are primitive and innate. This means we are born with them and they can't be broken down into simpler ideas.

However, some critics, like Kent Bach, disagreed. They argued that concepts like "VIXEN" (a female fox) are clearly made up of simpler concepts: "FEMALE" and "FOX." This suggests that not all concepts are primitive.

Books by Jerry Fodor

- Minds without meanings: an essay on the contents of concepts, with Zenon W. Pylyshyn, MIT Press, 2014, ISBN: 0-262-52981-5.

- What Darwin Got Wrong, with Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010, ISBN: 0-374-28879-8.

- LOT 2: The Language of Thought Revisited, Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN: 0-19-954877-3.

- Hume Variations, Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN: 0-19-928733-3.

- The Compositionality Papers, with Ernie Lepore, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN: 0-19-925216-5.

- The Mind Doesn't Work That Way: The Scope and Limits of Computational Psychology, MIT Press, 2000, ISBN: 0-262-56146-8.

- In Critical Condition, MIT Press, 1998, ISBN: 0-262-56128-X.

- Concepts: Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong, The 1996 John Locke Lectures, Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN: 0-19-823636-0.

- The Elm and the Expert: Mentalese and Its Semantics, The 1993 Jean Nicod Lectures, MIT Press, 1994, ISBN: 0-262-56093-3.

- Holism: A Consumer Update, with Ernie Lepore (eds.), Grazer Philosophische Studien, Vol 46. Rodopi, Amsterdam, 1993, ISBN: 90-5183-713-5.

- Holism: A Shopper's Guide, with Ernie Lepore, Blackwell, 1992, ISBN: 0-631-18193-8.

- A Theory of Content and Other Essays, MIT Press, 1990, ISBN: 0-262-56069-0.

- Psychosemantics: The Problem of Meaning in the Philosophy of Mind, MIT Press, 1987, ISBN: 0-262-56052-6.

- The Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology, MIT Press, 1983, ISBN: 0-262-56025-9.

- Representations: Philosophical Essays on the Foundations of Cognitive Science, Harvard Press (UK) and MIT Press (US), 1979, ISBN: 0-262-56027-5.

- The Language of Thought, Harvard University Press, 1975, ISBN: 0-674-51030-5.

- The Psychology of Language, with T. Bever and M. Garrett, McGraw Hill, 1974, ISBN: 0-394-30663-5.

- Psychological Explanation, Random House, 1968, ISBN: 0-07-021412-3.

- The Structure of Language, with Jerrold Katz (eds.), Prentice Hall, 1964, ISBN: 0-13-854703-3.

See also

In Spanish: Jerry Fodor para niños

In Spanish: Jerry Fodor para niños

- Computational theory of mind

- Connectionism

- Folk psychology

- Functionalism (philosophy of mind)

- List of Jean Nicod Prize laureates

- Special sciences

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |