Hilary Putnam facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hilary Putnam

|

|

|---|---|

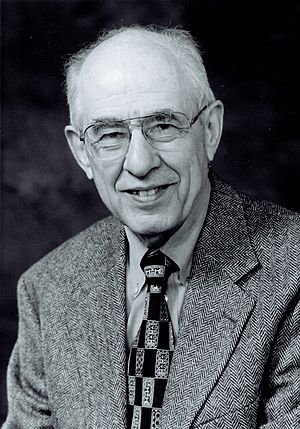

Putnam in 2006

|

|

| Born |

Hilary Whitehall Putnam

July 31, 1926 |

| Died | March 13, 2016 (aged 89) Arlington, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | University of Pennsylvania Harvard University University of California, Los Angeles |

| Spouse(s) | Ruth Anna Putnam |

| Awards | Rolf Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy (2011), Nicholas Rescher Prize for Systematic Philosophy (2015) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic Neopragmatism Postanalytic philosophy Mathematical quasi-empiricism Metaphysical realism (1983) Internal realism Direct realism (1994) Transactionalism (2012) |

| Institutions | Northwestern University Princeton University MIT Harvard University |

| Thesis | The Meaning of the Concept of Probability in Application to Finite Sequences (1951) |

| Doctoral advisor | Hans Reichenbach |

|

Main interests

|

Philosophy of mind, of language, of science, and of mathematics Metaphilosophy Epistemology Jewish philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Multiple realizability of the mental Functionalism Causal theory of reference Semantic externalism (reference theory of meaning) Brain in a vat · Twin Earth Putnam's model-theoretical argument against metaphysical realism (Putnam's paradox) Internal realism Quine–Putnam indispensability thesis Davis–Putnam algorithm Criticism of the innateness hypothesis |

Hilary Whitehall Putnam (July 31, 1926 – March 13, 2016) was an American thinker. He was a philosopher, a mathematician, and a computer scientist. He was a very important person in analytic philosophy during the second half of the 20th century.

Putnam made big contributions to how we understand the mind, language, mathematics, and science. Beyond philosophy, he also helped in mathematics and computer science. For example, he worked with Martin Davis to create the Davis–Putnam algorithm. This algorithm helps solve complex logic problems. He also helped show that a famous math problem, Hilbert's tenth problem, could not be solved.

Putnam was known for always questioning his own ideas, just as much as he questioned others'. He would analyze each idea carefully until he found its weak points. Because of this, he often changed his mind about philosophical topics. In the philosophy of mind, Putnam is famous for his idea of multiple realizability. This means that a mental state, like pain, can happen in different ways in different kinds of brains. He also helped develop functionalism, a key idea about how the mind and body are connected.

In the philosophy of language, Putnam helped create the causal theory of reference. This theory explains how words get their meaning. He also came up with the idea of semantic externalism. This means that the meaning of words depends on things outside our minds. He used a famous thought experiment called Twin Earth to explain this.

In the philosophy of mathematics, Putnam and W. V. O. Quine argued that mathematical things are real because they are needed for science. Later, Putnam believed that mathematics is not just about pure logic. He thought it was also a bit "quasi-empirical", meaning it uses ideas from experience. In epistemology (the study of knowledge), Putnam is known for questioning the "brain in a vat" thought experiment. This experiment suggests we might just be brains in a vat, but Putnam argued that this idea doesn't make sense.

In metaphysics (the study of reality), he first believed in metaphysical realism. This is the idea that reality exists completely separate from our minds. But he later changed his mind and became a strong critic of this view. He then adopted a view he called "internal realism", which he also later changed. Even with these changes, Putnam always believed in scientific realism. This is the idea that good scientific theories give us a true picture of how things really are.

In his later years, Putnam became more interested in American pragmatism, Jewish philosophy, and ethics. He also thought about metaphilosophy, which is the philosophy of philosophy itself. He wanted to "renew philosophy" from what he saw as narrow concerns. He was sometimes involved in politics, especially with the Progressive Labor Party in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Contents

Life and Education

Hilary Whitehall Putnam was born on July 31, 1926, in Chicago, Illinois. His father, Samuel Putnam, was a writer and translator. His father wrote for a communist newspaper, so Hilary had a non-religious upbringing. However, his mother, Riva, was Jewish. In 1927, when Hilary was six months old, his family moved to France. Hilary said his first memories were from France, and his first language was French.

Putnam went to primary school in France for two years. Then, in 1933, his family moved back to the U.S. and settled in Philadelphia. He went to Central High School. There, he met Noam Chomsky, who was a year younger. They remained friends and often debated ideas throughout their lives.

Putnam studied philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania. He then did more study at Harvard University and later at UCLA. He earned his Ph.D. in 1951. His main teacher, Hans Reichenbach, was a leader in a philosophy movement called logical positivism. Putnam, however, always disagreed with logical positivism. Throughout his life, Putnam often challenged his own ideas, changing his views and critiquing his earlier thoughts.

After getting his Ph.D., Putnam taught at Northwestern University (1951–52), Princeton University (1953–61), and MIT (1961–65). In 1962, he married Ruth Anna Putnam, who was also a philosopher. They decided to create a traditional Jewish home for their children. They learned about Jewish rituals and Hebrew. They became very interested in Judaism and actively practiced it. In 1994, Hilary had a bar mitzvah service, which is a special Jewish ceremony for becoming an adult.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Putnam strongly supported the American Civil Rights Movement. He also actively opposed the Vietnam War. In 1963, he helped start one of MIT's first anti-war groups for teachers and students. After moving to Harvard in 1965, he organized protests and taught courses on Marxism. He became an advisor for the Students for a Democratic Society. In 1968, he joined the Progressive Labor Party (PLP). Harvard tried to criticize Putnam for his activities. He left the PLP in 1972. Later, in 1997, he said that joining the PLP was a mistake.

In 1976, Putnam became president of the American Philosophical Association. He retired from teaching in 2000. Even after retiring, he continued to give seminars at Tel Aviv University. He also held a special philosophy position at the University of Amsterdam in 2001. He wrote many books and over 200 articles. His renewed interest in Judaism led him to publish books and essays on that topic. With his wife, he also wrote about the American pragmatist movement.

For his work in philosophy and logic, Putnam received the Rolf Schock Prize in 2011 and the Nicholas Rescher Prize for Systematic Philosophy in 2015. Hilary Putnam passed away at his home in Arlington, Massachusetts, on March 13, 2016.

Philosophy of Mind

Understanding Mental States

Putnam's most famous work is about the philosophy of mind. He made important contributions in the late 1960s with his idea of multiple realizability.

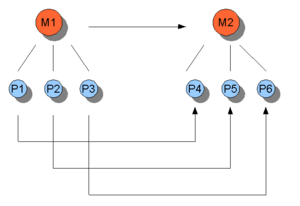

Multiple Realizability Explained

Putnam argued against the idea that a mental state, like pain, always matches one specific physical state in the brain. He said that pain could be caused by very different physical states in the nervous systems of different living things. For example, a human's brain might experience pain one way. But a dog's brain, or even an alien's brain, might experience the same feeling of pain in a totally different physical way.

He used examples from animals to show this. Is it likely that a human's brain and a bird's brain create pain in the exact same physical way? Probably not. If their brain structures are different, then the mental state of pain must be created by different physical states in each species. Putnam even thought about artificial intelligence (AI) and robots. He said that these hypothetical beings should be able to feel pain, even if they don't have human brains.

Putnam concluded that the idea that mental states always match one specific physical state was "highly unlikely." He believed that just one example of multiple realizability could prove this idea wrong.

Functionalism: What Things Do

Putnam and other philosophers argued that because of multiple realizability, we need a different way to explain mental things. This led to functionalism. Functionalism says that mental states are defined by what they do (their function), not by what they are made of.

Think of a mousetrap. A mousetrap's function is to catch mice. It doesn't matter if it's made of wood, plastic, or metal. As long as it performs the function of catching mice, it's a mousetrap. In the same way, functionalism suggests that a mental state like "being in pain" is defined by its function. For example, it makes you cry "ouch" or try to find out what's causing the pain. The physical details of how it happens in the brain are less important.

Putnam Changes His Mind

Later, in the 1980s, Putnam stopped supporting functionalism. One reason was the difficulty functionalism had explaining semantic externalism. This is the idea that the meaning of our thoughts depends on things outside our minds. His own Twin Earth thought experiment helped show this problem.

Even though Putnam changed his mind, functionalism is still a very important idea. It helped create modern cognitive science, which studies how the mind works. It's still a leading theory in philosophy today.

Other thinkers have also criticized functionalism. John Searle created the Chinese room argument. This argument suggests that a system can follow rules and seem intelligent without truly understanding anything. Imagine a person in a room who only speaks English. They are given Chinese symbols and a rule book in English that tells them how to move the symbols around. People outside the room, who speak Chinese, give symbols and receive symbols. The person inside is just following rules, not understanding Chinese. Searle argued that this shows that just following rules (like a computer) doesn't mean there's real understanding or meaning.

Philosophy of Language

Meaning Outside the Head

One of Putnam's key ideas in the philosophy of language is semantic externalism. This means that the meaning of words is not just in our minds. It's also determined by things in the world around us. He famously said, "meaning just ain't in the head."

The Twin Earth Experiment

Putnam used his "Twin Earth" thought experiment to explain this. Imagine a planet called Twin Earth. Everything on Twin Earth is exactly like Earth, except for one thing: their "water" is not H2O. Instead, it's a different chemical called XYZ.

Now, imagine a person on Earth, Fredrick, uses the word "water." He means H2O. On Twin Earth, his exact physical copy, Frodrick, uses the word "water." But Frodrick means XYZ. Since Fredrick and Frodrick are physically identical (even their brains are the same), but their word "water" has different meanings, Putnam argued that meaning can't be only in their heads. It must also depend on what's in the world around them. This idea changed how many philosophers thought about meaning.

How Words Get Their Meaning

Putnam also helped develop the causal theory of reference. This theory says that words, especially those for natural things like "tiger" or "water," get their meaning from the actual objects they refer to.

He believed there's a "linguistic division of labor." This is like how different people have different jobs in a factory. In language, experts in a certain field "fix" the meaning of certain words. For example, zoologists define what a "lion" is. Botanists define what an "elm tree" is. Chemists define "table salt" as sodium chloride. These meanings then spread to everyone else who uses the language.

Putnam suggested that the meaning of every word can be described using four parts:

- The actual thing the word refers to (like H2O for water).

- Typical descriptions of the word (like "transparent" or "colorless" for water).

- Categories the object belongs to (like "natural kind" or "liquid").

- Grammar rules for the word (like "concrete noun").

This "meaning-vector" helps us understand how a word is used and if its meaning has changed. Putnam believed that a word's meaning only truly changes if the thing it refers to changes, not just its common descriptions.

Philosophy of Mathematics

Why Math is Real

In the philosophy of mathematics, Putnam argued that mathematical things are real. He used an argument called the indispensability argument.

The Indispensability Argument

Putnam, along with W. V. O. Quine, argued that we need mathematical ideas and numbers to do science, both in pure math and in physics. Since we need them, we should accept that these mathematical things exist.

Putnam also made his own version of this argument. He said that if mathematics wasn't real, then the success of science would be a "miracle." Science uses math all the time to make predictions and understand the world. If math was just made up, how could it work so perfectly? Putnam believed that accepting math as real is the only way to explain why science is so successful.

Math and Experience

Putnam also thought that mathematics, like physics, uses both strict logical proofs and "quasi-empirical" methods. This means that sometimes, mathematicians use ideas that are like experiments or observations.

For example, Fermat's Last Theorem says that for numbers bigger than 2, you can't find positive whole numbers x, y, and z where xn + yn = zn. Before Andrew Wiles proved this for all numbers in 1995, it had been proven for many specific numbers. These proofs led to more research and created a strong belief that the theorem was true, even without a full proof. This is a bit like how science works, where observations lead to strong conclusions.

The indispensability argument has been very important in the philosophy of mathematics. Many experts think it's the best argument for believing that mathematical things are real.

Math and Computer Science

Putnam also made important contributions to science outside of philosophy.

Solving Math Problems

As a mathematician, he helped solve Hilbert's tenth problem. This problem was finally solved by Yuri Matiyasevich in 1970. His proof relied a lot on earlier work by Putnam, Julia Robinson, and Martin Davis.

In computer science, Putnam is known for the Davis–Putnam algorithm. He developed this with Martin Davis in 1960. This algorithm helps figure out if a complex logical statement can be true. In 1962, they improved the algorithm with George Logemann and Donald W. Loveland. This improved version, called the DPLL algorithm, is still used today in many computer programs that solve logic problems.

Epistemology (The Study of Knowledge)

The "Brain in a Vat" Argument

In epistemology, Putnam is famous for his argument against the "brain in a vat" thought experiment. This is a modern version of Descartes's idea of an evil demon tricking us. The "brain in a vat" idea suggests that you might just be a brain in a vat, with a mad scientist feeding you all your experiences through wires. Putnam argued that you can't logically believe this is true.

His argument comes from his causal theory of reference. This theory says that words refer to the kinds of things they were first used to talk about. These are things that the person using the word, or their ancestors, actually experienced.

So, if a person, Mary, is a "brain in a vat," all her experiences come from the scientist's wiring. Her idea of a "brain" doesn't refer to a real brain, because she and her language group have never actually seen one. To her, a "brain" is just an image sent to her through the wires. The same goes for her idea of a "vat."

So, if Mary, as a brain in a vat, says, "I'm a brain in a vat," she's actually saying, "I'm a brain-image in a vat-image." This doesn't make sense. On the other hand, if she's not a brain in a vat, then saying she is one is also wrong. This means that the idea of being a brain in a vat is always illogical.

Putnam said his real goal with this argument was not just to fight skepticism. He wanted to challenge metaphysical realism. This idea suggests there's a gap between how we see the world and how the world truly is. Skeptical ideas like the "brain in a vat" make this gap seem possible. By showing that such a scenario is illogical, Putnam tried to show that the idea of this gap is absurd. We can't have a "God's-eye" view of reality. We are limited by our own ways of thinking about things.

Metaphilosophy and Reality

Internal Realism: How We Shape Reality

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Putnam changed his mind about metaphysical realism. He had believed that the world's categories and structures exist completely separate from the human mind. But he then adopted a different view called "internal realism" or "pragmatic realism".

Internal realism says that while the world might exist independently of our minds, the way the world is structured (how it's divided into different kinds of things) depends on the human mind. So, the world isn't completely independent of us. This idea was influenced by Immanuel Kant, who thought our knowledge of the world depends on our ways of thinking.

Putnam believed that metaphysical realism couldn't explain how our ideas and words refer to things in the world. How could our ideas perfectly match the world's own structures? His answer was that the world doesn't come pre-structured. Instead, the human mind and its ways of thinking give structure to the world. He thought that a belief is true if it would be accepted by anyone under perfect thinking conditions.

Putnam accepted "conceptual relativity." This means there can be many correct ways to describe reality. None of these descriptions can be scientifically proven to be the "one, true" way the world is.

Later, Putnam stopped believing in internal realism. He became more influenced by William James and other pragmatists. He then adopted a direct realist view. This means he believed that when we see something, we are directly seeing the external world, not just a mental picture of it. Even though he changed his mind about internal realism, Putnam still believed that no single thing or system can be described in only one complete and correct way.

See also

In Spanish: Hilary Putnam para niños

In Spanish: Hilary Putnam para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |