History of economic thought facts for kids

The history of economic thought looks at the ideas and theories about how people manage money, resources, and trade. These ideas eventually grew into what we now call economics. This field covers many different ways of thinking about how economies work.

For example, in ancient Greece, thinkers like Aristotle wondered about how people get rich and if things should be owned by individuals or by everyone. Later, in the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas believed that businesses had a moral duty to sell goods at a fair price. Until the 1700s and 1800s, economics wasn't a separate subject. It was usually part of philosophy.

Contents

- Early Economic Ideas (Before 500 AD)

- Economic Ideas in the Middle Ages (500–1500 AD)

- Mercantilism and Global Trade (16th to 18th Century)

- School of Salamanca: Early Economic Theory

- Sir Thomas More: An Ideal Society

- Nicolaus Copernicus: Money's Value

- Jean Bodin: Understanding Inflation

- Barthélemy de Laffemas: Jobs for the Poor

- Leonardus Lessius: Risk and Insurance

- Edward Misselden and Gerard Malynes: Free Trade vs. Regulation

- Thomas Mun: Mercantilist Policy

- Sir William Petty: Scientific Economics

- Philipp von Hörnigk: National Power

- Jean-Baptiste Colbert and Pierre Le Pesant: Regulating Industries

- Charles Davenant: Consumer Demand

- Sir James Steuart: Political Economy

- Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb: Islamic Economics

- Pre-Classical Ideas (17th and 18th Century)

- Classical Economics (18th and 19th Century)

- Ferdinando Galiani: Modern Money Analysis

- Adam Smith: The Wealth of Nations

- Adam Smith's Invisible Hand

- William Pitt the Younger: Following Smith's Ideas

- Edmund Burke: A Friend of Smith's Ideas

- Jeremy Bentham: The Greatest Good

- Jean-Baptiste Say: Supply Creates Demand

- David Ricardo: Trade and Income Distribution

- John Stuart Mill: A Leading Economist

- Classical Political Economy: Labor and Growth

- Marxian Critique of Political Economy

- Henry George and Georgism: Poverty Amidst Progress

- The London School of Economics

- Neoclassical Economics (19th and Early 20th Century)

- World Wars, Revolution, and Great Depression (Early to Mid-20th Century)

- Econometrics: Using Math and Computers

- Corporate Governance: Who Controls Big Companies?

- Industrial Organization Economics: Competition in Markets

- Linear Programming: Allocating Resources

- Ecology and Energy: Resources and Sustainability

- Institutional Economics: Relationships in the Economy

- Arthur Cecil Pigou: Market Failures

- Market Socialism: Combining Ideas

- The Stockholm School of Economics: Welfare State Ideas

- The American Economic Association

- Keynesianism (20th Century)

- The Chicago School of Economics (20th Century)

- Games, Evolution, and Growth (20th Century)

- Post World War II and Globalization (Mid to Late 20th Century)

- International Economics: Trade and Development

- Development Economics: Helping Poorer Countries

- New Economic History (Cliometrics)

- Public Choice Theory: Economics of Politics

- Impossible Trinity: International Finance Choices

- Market for Corporate Control

- Information Economics: When Information Isn't Perfect

- Market Design Theory: Designing Better Markets

- The Laffer Curve and Reaganomics: Taxes and Revenue

- Market Regulation: Understanding Market Power

- After the 2008 Financial Crisis (21st Century)

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Economic Ideas (Before 500 AD)

Ancient Greece: Thinking About Scarcity

Hesiod, who lived around 750 to 650 BC, was one of the first to write about basic economic problems. In his poem Works and Days, he talked about how people have many wants and desires, but there are only limited resources to meet them. This is a core idea in economics!

China: Rules for Business

Fan Li (born 517 BC) was an advisor to a king. He wrote about economic topics and created "golden" rules for business. Later, a debate called Discourses on Salt and Iron discussed whether the government should control businesses or let them operate freely.

India: Ancient Wisdom on Wealth

Ancient Hindu texts like the Vedas (from 1700 BCE to 1100 BCE) contain some economic ideas. The Atharvaveda (around 1200 BCE) talks a lot about these ideas.

Chanakya (born 350 BC) from the Maurya Empire wrote the Arthashastra. This book was about how to run a state, including economic policies and military plans. It said that understanding economics (called Varta) was one of four key areas of knowledge needed for wealth and human success.

Greco-Roman World: Property and Money

Ancient Athens was an advanced city that developed early forms of democracy.

Xenophon (around 430–354 BC) wrote Oeconomicus, which was mostly about managing a household and farming.

Plato (around 380–360 BC) wrote The Republic, describing an ideal city. He mentioned how people specialize in different jobs and how goods are produced. Some historians believe Plato was the first to suggest that money is just a way to keep track of debt. Plato also thought that if everyone owned things together, it would help people work for the common good.

Aristotle (around 350 BC) looked at different types of governments in his book Politics. He disagreed with Plato's idea of common ownership. Aristotle believed it was better for property to be private, but for people to use it in a way that benefits everyone. He also thought that getting wealth for your household was "necessary and honorable." However, he strongly disliked making money just by lending it at high interest (usury) or by having a monopoly (being the only seller).

Aristotle also thought that money gets its value from the actual metal it's made of, like gold or silver. He said that money is just a tool, and someone rich in money could still starve, like the mythical king Midas.

Economic Ideas in the Middle Ages (500–1500 AD)

Thomas Aquinas: The Just Price

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) was an Italian scholar who taught in Cologne and Paris. He was part of a group called the Schoolmen, who studied philosophy and science in addition to religion. In his book Summa Theologica, Aquinas discussed the idea of a just price. He believed a fair price was one that covered the costs of making the goods and supported the worker and their family. Aquinas thought it was wrong for sellers to raise prices just because buyers really needed something. He also said that cheating was immoral and that people should always pay for good service.

Duns Scotus: Costs and Trade

One of Aquinas's critics was Duns Scotus (1265–1308) from Scotland. He thought it was possible to be more exact in figuring out a just price. He focused on the costs of labor and other expenses. Scotus also believed that merchants played an important role by moving goods and making them available to people.

Jean Buridan: Money's Value

Jean Buridan (around 1300 – after 1358) was a French priest. He looked at money in two ways: its value as metal and its buying power, which he knew could change. He argued that market prices are set by the total demand and supply of many people, not just one person. So, for him, a just price was what society as a whole was willing to pay.

Ibn Khaldun: Taxes and Civilizations

For a long time, Adam Smith was called the "Father of Economics." But now, some people consider Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), an Arab Muslim scholar from Tunisia, as another important early economist. He wrote about how civilizations grow and decline, how jobs specialize, and how money is a way to exchange things, not just something valuable in itself. His ideas on taxes even inspired the "Laffer curve," which suggests that if taxes are too high, people might produce less, and the government might actually collect less money.

Nicole Oresme: Who Controls Money?

French philosopher and priest Nicolas d'Oresme (1320–1382) wrote about money. He argued that money belongs to the public, and the government should not change its value just to make a profit.

Antonin of Florence: State's Role in Economy

Saint Antoninus of Florence (1389–1459) was an Italian friar and archbishop. He wrote that the government has a duty to get involved in business for the good of everyone. He also believed the state should help the poor. He thought there could be a range of "just prices" for goods, depending on how useful, rare, and desired they were.

Mercantilism and Global Trade (16th to 18th Century)

Mercantilism was the main economic idea in Europe from the 1500s to the 1700s. After explorers like Christopher Columbus opened up new trade routes, powerful kings wanted stronger countries. Mercantilism was a political and economic idea that said a country should use its military power to protect its own markets and resources. This led to protectionism, where countries tried to limit imports.

Mercantilists believed that international trade couldn't benefit all countries at the same time. They thought that money and precious metals were the only true wealth. So, they encouraged exports (selling goods to other countries) to bring money in and discouraged imports (buying goods from other countries) to keep money at home. This meant having a positive balance of trade, often supported by military strength. The term "mercantilism" was actually coined much later by Victor de Riqueti, marquis de Mirabeau in 1763 and made popular by Adam Smith, who strongly disagreed with it.

School of Salamanca: Early Economic Theory

In the 1500s, the Jesuit School of Salamanca in Spain developed advanced economic theories. Their ideas were largely forgotten until the 20th century.

Sir Thomas More: An Ideal Society

In 1516, English writer Sir Thomas More (1478–1535) published Utopia. This book described an ideal society where land was owned by everyone, and there was education and religious freedom for all. It inspired later ideas about helping the poor and even communism.

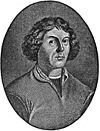

Nicolaus Copernicus: Money's Value

In 1517, the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) wrote about the idea that the amount of money in circulation affects prices. He also described what's now known as Gresham's law: "Bad money drives out good" (meaning if there are two types of money, people will spend the less valuable one and save the more valuable one).

Jean Bodin: Understanding Inflation

In 1568, Jean Bodin (1530–1596) from France wrote about inflation for the first time. He believed it was caused by too much gold and silver coming into the country from South America.

Barthélemy de Laffemas: Jobs for the Poor

In 1598, French economist Barthélemy de Laffemas (1545–1612) wrote that making French silks was good because it created jobs for the poor. This was an early idea related to "underconsumption theory," which suggests that if people don't buy enough, the economy suffers.

Leonardus Lessius: Risk and Insurance

In 1605, Flemish theologian Leonardus Lessius (1554–1623) wrote about justice and law in economics. He was the first to say that the price of insurance should be based on risk.

Edward Misselden and Gerard Malynes: Free Trade vs. Regulation

In 1622, English merchants Edward Misselden and Gerard Malynes debated about free trade and whether the government should control companies. Malynes thought bankers controlled foreign exchange, while Misselden argued that international trade affected exchange rates, and the state should regulate trade to ensure more exports than imports.

Thomas Mun: Mercantilist Policy

English economist Thomas Mun (1571–1641) described early mercantilist ideas in his book England's Treasure by Foreign Trade. He was a member of the East India Company and wrote about his experiences.

Sir William Petty: Scientific Economics

In 1662, English economist Sir William Petty (1623–1687) started writing about economics in a scientific way. He believed in using measurable facts and statistics, calling it "political arithmetic." He is considered the first scientific economist.

Philipp von Hörnigk: National Power

Philipp von Hörnigk (1640–1712) was an Austrian civil servant. In his book Austria Over All, If She Only Will (1684), he clearly explained mercantilist policies. He listed nine rules, including inspecting the country's resources, processing goods within the country, having a large population, keeping gold and silver inside the country, using domestic products, and selling manufactured goods to foreigners. His main ideas were about nationalism, self-sufficiency, and national power.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert and Pierre Le Pesant: Regulating Industries

From 1665 to 1683, Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683) was the finance minister for King Louis XIV of France. He created national guilds to control major industries like silk and furniture making. Colbert believed that a country's greatness and power came from having a lot of money.

In 1695, French economist Pierre Le Pesant, sieur de Boisguilbert (1646–1714) asked King Louis XIV to end Colbert's mercantilist policies. He was one of the first economists to question mercantilism and to value a country's wealth by the goods it produced and traded, rather than just its money.

Charles Davenant: Consumer Demand

In 1696, British politician Charles Davenant (1656–1714) showed an early understanding of consumer demand and perfect competition in his book Essay on the East India Trade.

Sir James Steuart: Political Economy

In 1767, Scottish economist Sir James Steuart (1713–1780) published An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy. This was the first complete book on economics in English, using the term "political economy" in its title.

-

Sir James Steuart (1713–1780)

Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb: Islamic Economics

Emperor Aurangzeb of Mughal India put together the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, a collection of Islamic laws that included Islamic economics. His policies helped lead to a period of early industrial growth in South Asia.

Pre-Classical Ideas (17th and 18th Century)

The British Enlightenment: Self-Interest and Markets

In the 1600s, Britain went through big changes, including civil war and scientific discoveries like Isaac Newton's laws of motion. These events pushed economic thinking forward. Thinkers like Richard Cantillon (1680–1734) compared economic forces to natural forces like gravity. He believed that people acting in their own self-interest in free markets would lead to order and fair prices. Unlike mercantilists, he thought wealth came from human labor, not just trade.

John Locke: Property Rights

John Locke (1632–1704) was an important philosopher. He believed that governments should protect people's property rights, which included their lives, freedoms, and wealth. He said that when people work on something, they create property rights over it. Locke also argued that the price of anything depends on how many buyers and sellers there are.

Dudley North: Benefits of Trade

Dudley North (1641–1691) was a rich merchant who disagreed with most mercantilist ideas. He wrote that trade benefits everyone involved and encourages people to specialize in what they do best, leading to more wealth for all. He thought government rules on trade got in the way of these benefits.

David Hume: Trade Balance is Impossible

David Hume (1711–1776) agreed with North. He argued that trying to have a constant trade surplus (more exports than imports) was impossible. He said that if a country exported too much, it would get more gold and silver, which would make prices go up. Higher prices would then make exports fall until the trade balance was back to normal.

Bernard Mandeville: Private Vices, Public Benefits

Bernard Mandeville (1670–1733) was a philosopher who wrote that people's selfish actions (vices) could actually lead to good things for society. He believed that luxury and self-interest could make society more active and progressive through inventions and the flow of money.

Francis Hutcheson: Managing the Household

Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746) was Adam Smith's teacher. He is seen as the end of a long tradition of thinking about economics as "household management," an idea that started with Xenophon.

The Physiocrats: Nature's Economy

The French Physiocrats were also unhappy with trade regulations. They believed that agriculture was the true source of wealth. They thought that cities were artificial and praised a more natural way of life focused on farming.

Just as doctors discovered how blood circulates in the human body, the Physiocrats thought about how money flows through the economy.

François Quesnay (1694–1774) was a doctor to the French king. He believed that trade and industry didn't create wealth. In his book Tableau économique (1758), he argued that farm surpluses, when they flowed through the economy as rent, wages, and purchases, were the real drivers of the economy. He said that rules stopped this flow and that taxes on farmers should be lowered, while taxes on landowners should be raised.

Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) was another Physiocrat. In his book Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth (1766), he also said that land was the only source of wealth. He divided society into three groups: farmers, paid workers, and landowners. He argued that only the profit from land should be taxed and that trade and industry should be completely free. Turgot became a finance minister and tried to remove old feudal rules, but he faced strong opposition and was forced out of office.

Classical Economics (18th and 19th Century)

Ferdinando Galiani: Modern Money Analysis

In 1751, Italian philosopher Ferdinando Galiani published Della Moneta (On Money). This book, written 25 years before Adam Smith's famous work, covered many modern ideas about money, its value, and inflation. It's seen as one of the first truly modern economic analyses.

Adam Smith: The Wealth of Nations

Adam Smith (1723–1790) is widely considered the father of modern economics. His book An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, came out during the American Revolution and at the start of the Industrial Revolution, which allowed for much more wealth to be created.

Smith was a Scottish philosopher. His first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), talked about how people's sense of right and wrong develops through their interactions with others. While this book was popular, The Wealth of Nations was initially ignored by the general public. However, it became very important among influential thinkers.

Adam Smith's Invisible Hand

Smith believed in a "system of natural liberty" where individuals working for themselves would create good for society. He thought that even selfish people would help everyone when they acted in a competitive market. He famously said: "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest."

Smith believed that the true value of things came from the amount of labor put into them. When many buyers and sellers compete, prices adjust to their fair values. If there's too much of something, the price falls. If there's not enough, the price rises.

Government's Role

Smith thought the government had three main jobs:

- Protecting the country from other nations.

- Keeping law and order.

- Building and maintaining public works, like roads or schools, that no individual would build alone.

He also criticized cartels (groups of businesses that secretly agree to control prices) and monopolies (when one company controls an entire market). He believed these could harm consumers by limiting production and charging high prices.

William Pitt the Younger: Following Smith's Ideas

William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806), who became the British Prime Minister, based his tax ideas on Smith's work. He was a strong believer in free trade.

Edmund Burke: A Friend of Smith's Ideas

Adam Smith admired the ideas of Irish politician Edmund Burke (1729–1797), saying Burke thought about economic topics exactly as he did. Burke was also an economist and criticized the French Revolution. Many thinkers of this time, including Smith, tried to explain the big social changes happening during the Industrial Revolution and show that there was still order in the world.

Jeremy Bentham: The Greatest Good

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) was a very forward-thinking person. He developed the idea of utilitarianism, which means aiming for "the greatest good for the greatest number" of people. He supported many ideas that were radical for his time, like universal suffrage (everyone being able to vote) and free trade.

Jean-Baptiste Say: Supply Creates Demand

Jean-Baptiste Say (1767–1832) was a French economist who helped make Adam Smith's ideas popular in France. In his book A Treatise on Political Economy (1803), he wrote about what became known as Say's Law. This law says that there can never be a general lack of demand in the economy. People produce things to meet their own needs, so producing goods actually creates demand for other goods. Say also believed that money was neutral, meaning its only purpose was to make exchanges easier.

David Ricardo: Trade and Income Distribution

David Ricardo (1772–1823) was a wealthy stock market trader from London. His most famous book is On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817). In it, he criticized barriers to international trade and described how income is shared among different groups: workers (who get wages to survive), landowners (who get rent), and capitalists (who own capital and get profit).

Ricardo believed that if the population grew, people would need to farm less fertile land. This would make food more expensive, increasing rents and wages. Profits would then fall, eventually stopping new investments and leading the economy to a "steady state."

John Stuart Mill: A Leading Economist

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) was a dominant figure in economic thought during his time. He was a child genius who read Ancient Greek at age 3. His textbook, Principles of Political Economy (1848), summarized the economic ideas of the mid-1800s and was used in universities for many years. Mill tried to find a middle ground between Adam Smith's idea of endless growth and Thomas Malthus's idea of population limits.

Classical Political Economy: Labor and Growth

The classical economists were a group first identified by Karl Marx. A key idea for them was the labour theory of value, which said that the value of something comes from the labor put into it. They saw the big changes from the Industrial Revolution, like people moving from farms to cities, poverty, and the rise of a working class.

They wondered about population growth and asked basic questions about where value comes from, what makes economies grow, and the role of money. They supported a free-market economy, believing it was a natural system based on freedom and property.

One important idea within classical economics was "underconsumption theory," which suggested that governments should act to reduce unemployment and economic slowdowns. This was an early version of what later became Keynesian economics.

Marxian Critique of Political Economy

Karl Marx (1818–1883) wrote his major work, Das Kapital (Capital), in London. He started by looking at "commodities" (things that are produced to be sold). He believed that before capitalism, production was based on slavery or serfdom. Marx thought that capitalism would eventually lead to an unstable situation that would cause a revolution.

Marx said that commodities have two sides: their use value (how useful they are) and their exchange value (what they can be traded for). He argued that the value of a commodity comes from the "human labor" put into it.

Marx believed that a "reserve army of the unemployed" (people looking for jobs) would grow, pushing wages down. But this would mean people couldn't buy as many products, leading to unsold goods, reduced production, and falling profits. This would cause an economic depression. He thought that with each economic crisis, the tension between capitalists and workers would increase.

Henry George and Georgism: Poverty Amidst Progress

Henry George (1839–1897) was a very famous American economist. His book, Progress and Poverty, was one of the most widely printed books in English. It explored why poverty often exists even when a society is making progress. George's ideas, known as Georgism, sparked a worldwide reform movement. He is considered the last classical economist.

The London School of Economics

In 1895, the London School of Economics (LSE) was founded by members of the Fabian Society, including Sidney Webb (1859–1947), Beatrice Webb (1858–1943), and George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950). Later, in the 1930s, LSE member Sir Roy G.D. Allen (1906–1983) helped make mathematics popular in economics.

Neoclassical Economics (19th and Early 20th Century)

Neoclassical economics started in the 1870s. There were three main groups of thinkers. The Cambridge School, with economists like Stanley Jevons and Alfred Marshall, focused on market failures. The Austrian School, including Carl Menger, tried to explain economic crises. The Lausanne School, led by Léon Walras, developed theories about how the entire economy reaches a balance.

Anglo-American Neoclassical Ideas

American economist John Bates Clark (1847–1938) helped popularize the idea of "marginalism." This means looking at the extra benefit or cost of one more unit of something. He proposed that in a competitive market, what a social class earns is what it contributes to the overall production.

William Stanley Jevons: Diminishing Utility

In 1871, Stanley Jevons (1835–1882) published Theory of Political Economy. He explained the idea of diminishing marginal utility. This means that the more of something you have or consume, the less extra satisfaction you get from each additional unit. For example, the first slice of pizza is amazing, but the tenth slice might not be as satisfying.

Alfred Marshall: Principles of Economics

Alfred Marshall (1842–1924) was the first economics professor at the University of Cambridge. His 1890 book Principles of Economics became a key textbook. He preferred the term "economics" over "political economy." Marshall believed math could simplify economic reasoning, but he also thought it was important to explain ideas clearly in plain English.

Continental Neoclassical Ideas

Léon Walras: General Equilibrium

In 1874, French economist Léon Walras (1834–1910) developed the idea of "general equilibrium." He showed how changes in people's preferences for one product (like mushrooms instead of beef) could cause prices to shift across the entire economy. This would lead to producers changing what they make, eventually reaching a new balance of prices. This assumes markets are competitive and people act in their own self-interest.

The Austrian School of Economics

While many economists started using more math, the Austrian School of Economics (led by Carl Menger and his students Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and Friedrich von Wieser) focused on using logical reasoning instead.

Carl Menger: Consumer Satisfaction

In 1871, Austrian economist Carl Menger (1840–1921) explained the idea of marginal utility again in his book Principles of Economics. He said that consumers act logically by trying to get the most satisfaction from their choices. People spend their money so that the last unit of something they buy gives them the same amount of satisfaction as the last unit of anything else they buy.

Friedrich Hayek: Spontaneous Order

Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992) was an important economist from the Austrian School. He believed that the market is a "spontaneous order," meaning it organizes itself naturally without central planning. He argued that any form of central control over the economy would lead to less freedom and lower living standards. In his book The Road to Serfdom (1944), Hayek claimed that socialism, with its central planning, would lead to totalitarianism. He believed that price signals in a free market are the only way for people to share information and make good economic decisions. Hayek won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974.

World Wars, Revolution, and Great Depression (Early to Mid-20th Century)

During World War I (1914–1918), countries like Britain, Germany, and France shifted their production to military goods. After the war, Europe was in ruins. The Great Depression, which started in 1929, caused huge unemployment worldwide.

The most important economic idea during the Great Depression was the Keynesian revolution, led by John Maynard Keynes and his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936).

Econometrics: Using Math and Computers

In the 1930s, Norwegian economist Ragnar Frisch (1895–1973) and Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen (1903–1994) started the field of Econometrics. This is about using statistics and math to study economic data. They won the first Nobel Prize in Economics in 1969. Later, economists like Wassily Leontief (1905–1999) and Lawrence Klein (1920–2013) used computers to build economic models. Clive Granger (1934–2009) also used advanced math in economics.

Corporate Governance: Who Controls Big Companies?

The Great Depression made people think about what went wrong. Adolf Berle (1895–1971), a lawyer, and economist Gardiner C. Means (1896–1988) wrote The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932). They showed how big businesses had grown and argued that the people who controlled these companies (the directors) should be more accountable to the owners (the shareholders). They believed that directors might use company profits for themselves if they weren't properly overseen. Berle helped create many of the New Deal policies in the U.S. during the Depression.

Later, Berle and Means said that the purpose of companies should be to benefit society as a whole, not just a few shareholders.

Industrial Organization Economics: Competition in Markets

In 1933, American economist Edward Chamberlin (1899–1967) and British economist Joan Robinson (1903–1983) both published books about "monopolistic competition" and "imperfect competition." Their work started the field of Industrial Organization Economics, which studies how companies compete in markets.

Linear Programming: Allocating Resources

In 1939, Russian economist Leonid Kantorovich (1912–1986) developed Linear Programming. This is a math method for finding the best way to use limited resources. He won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1975.

Ecology and Energy: Resources and Sustainability

By the 20th century, the Industrial Revolution had led to a huge increase in how many resources humans used. But in the 1930s, economists started thinking about how to manage non-renewable resources and how to keep welfare going in an economy that uses them.

Concerns about the environment had been raised before. Thomas Malthus wrote about overpopulation, and John Stuart Mill thought about a "stationary state" economy, which means an economy that doesn't keep growing forever. These ideas are similar to what is now called ecological economics.

Ecological Economics

Ecological economics focuses on nature, fairness, and time. It looks at issues like how our actions affect future generations, how human impact on the environment can't be undone, and the limits to growth due to physics (thermodynamics).

Institutional Economics: Relationships in the Economy

In 1919, the term "Institutional economics" was created. In 1934, John R. Commons (1862–1945) published Institutional Economics. He believed that the economy is a network of relationships between people with different interests, like monopolies, big companies, and workers. He thought the government should act as a mediator to help resolve these conflicts.

Arthur Cecil Pigou: Market Failures

In 1920, Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877–1959), a student of Alfred Marshall, wrote Wealth and Welfare. He argued that markets can sometimes fail, especially when there are "economic externalities" (when an action affects someone who wasn't involved in the action, like pollution). In such cases, he believed the government should step in. However, he also thought that too much government involvement in the job market could cause unemployment.

Market Socialism: Combining Ideas

The idea of Market Socialism was developed in the late 1920s and 1930s by economists like Fred M. Taylor (1855–1932), Oskar R. Lange (1904–1965), and Abba Lerner (1903–1982). This theory combined ideas from Marxian economics with neoclassical economics, but without the labor theory of value. It was a response to arguments that a state-run economy couldn't be efficient.

The Stockholm School of Economics: Welfare State Ideas

In the 1930s, the Stockholm School of Economics was founded by economists like Eli Heckscher (1879–1952), Bertil Ohlin (1899–1977), and Gunnar Myrdal (1898–1987). Their ideas, influenced by John Maynard Keynes, helped shape the Swedish welfare state.

In 1933, Ohlin and Heckscher proposed a model of international trade. It said that countries export products that use their plentiful and cheap resources and import products that use their scarce resources. Ohlin later won a Nobel Prize in Economics.

The American Economic Association

In 1885, the American Economic Association (AEA) was founded by Richard T. Ely (1854–1943) and others. It publishes the American Economic Review, a major economics journal.

Keynesianism (20th Century)

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) was a very influential economist. He worked for the British government during World War I and was deeply unhappy with the peace treaty after the war. In his book The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), he warned that forcing Germany to pay huge war reparations would lead to a global financial crisis and another world war. His predictions sadly came true with the Great Depression and World War II.

After World War II, Keynes played a key role in setting up a new global economic system at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, which led to the creation of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

The General Theory: Solving the Depression

During the Great Depression, Keynes published his most important book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). The Depression, sparked by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, caused massive unemployment. Traditional economists said to cut spending and wait for the market to fix itself. Keynes disagreed, famously saying, "...in the long run we are all dead."

Keynes argued that economic activity depends on many things, including how much people consume and how much businesses invest. If people save too much and businesses don't invest enough, total spending falls, leading to lower incomes and unemployment. This creates a "depression equilibrium."

Keynes believed that governments needed to act. He suggested that deficit spending (when the government spends more than it collects in taxes) could kick-start the economy. He also advocated for low interest rates and easy credit to encourage investment. His ideas provided the basis for the New Deal policies in the U.S. and influenced Western governments to use government spending to avoid crises and keep people employed.

The Cambridge Circus: Expanding Keynes's Ideas

During World War II, Keynes advised the British government and helped create the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. After his death, his ideas continued to shape the global economy.

One of Keynes's students, Joan Robinson (1903–1983), argued that competition in markets is rarely perfect. She also questioned how neoclassical economists valued capital, suggesting it was a circular argument.

Alfred Eichner (1937–1988) was a post-Keynesian economist who believed that prices are set by companies adding a markup to their costs, not just by supply and demand. He thought investment was key to economic growth.

Richard Kahn (1905–1989), another member of Keynes's group, proposed the idea of the Multiplier in 1931. This means that an initial increase in spending can lead to a larger increase in overall economic activity.

Piero Sraffa (1898–1983) argued that technology and the relationships between different parts of production are the basis for goods and services. He showed that prices are influenced by things like wages, profits, and government planning, not just market adjustments.

John Hicks (1904–1989) developed the IS/LM Model, which shows how the money market and the goods market interact to reach a general balance in the economy.

New Keynesian Macroeconomics: Modernizing Keynes

In the late 20th century, New Keynesian Macroeconomics emerged. Economists like Edmund Phelps (1933–) and John B. Taylor (1946–) showed that if wages and prices don't change quickly (they are "sticky"), then government monetary policy can still help stabilize the economy. This brought Keynesian ideas back into the mainstream.

George Akerlof (1940–) and Janet Yellen (1946–) showed that even small reasons for prices to be "sticky" can have a big impact on the economy.

The Credit Theory of Money

In 1913, English economist Alfred Mitchell-Innes (1864–1950) published What is Money?, followed by The Credit Theory of Money in 1914. He argued that money is essentially a record of debt or credit, rather than just a commodity like gold.

The Chicago School of Economics (20th Century)

The Chicago School of Economics challenged the idea of strong government intervention. They believed that people are best left to make their own choices.

Ronald Coase (1910–2013) was a key figure in the Chicago School. He argued that companies exist because of "transaction costs" (the costs of doing business). He also said that if there were no transaction costs, people could bargain to reach the most efficient outcome, no matter what the law said. This meant that laws and regulations might not be as important as people think.

In the 1960s, Gary Becker (1930–2014) and Jacob Mincer (1922–2006) started "New Home Economics," which applied economic ideas to family decisions.

Richard Posner (1939–), a student of Coase, wrote Economic Analysis of Law (1973), which became a standard textbook. He argued that judges often interpret common law in a way that tries to maximize economic well-being.

Milton Friedman (1912–2006) was one of the most influential economists of the late 20th century. He won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976. He argued that the Great Depression was caused by the policies of the Federal Reserve. Friedman believed that governments should not interfere much in the economy. He thought they should aim for a stable money supply to support long-term economic growth. He argued that active government spending or easy credit could have negative effects. Friedman also developed the "Permanent Income Hypothesis," which says that people spend based on what they expect their long-term income to be.

New Classical Macroeconomics: Rational Expectations

In the early 1970s, Robert Lucas, Jr. (1937–) founded New Classical Macroeconomics. This school of thought, based on Friedman's ideas and the concept of "rational expectations" (that people make decisions based on all available information), argued against government intervention to stabilize the economy. Lucas won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1995.

Later, the "Real Business Cycle Theory," proposed by Finn Kydland (1943–) and Edward C. Prescott (1940–) in 1982, became the standard model. It suggests that economic ups and downs are caused by real factors like changes in technology, not just money. Kydland and Prescott also developed "Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium" (DSGE) models, which combine many small economic equations into models of the whole economy. They shared the Nobel Prize in 2004.

Efficient Market Hypothesis: Stock Market Randomness

In 1965, Chicago School economist Eugene Fama (1939–) proposed the Efficient Market Hypothesis. This idea says that stock market prices move randomly because a perfectly working financial market quickly reflects all available information. This means it's hard to predict stock prices.

Games, Evolution, and Growth (20th Century)

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (1883–1950) was an Austrian economist known for his work on business cycles and innovation. He believed that entrepreneurs (people who start new businesses) play a key role in the economy. Schumpeter argued that capitalism goes through cycles because it relies on new inventions and innovations. These innovations lead to growth, but eventually, the economy slows down until new innovations create a process of "creative destruction," where old products are replaced, and new growth begins.

In 1944, John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern published Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, starting Game Theory. This field studies how people make decisions when their outcomes depend on the choices of others. In 1951, John Forbes Nash Jr. defined the Nash equilibrium, a key concept in game theory.

In 1956, Robert Solow (1924–) and Trevor Swan (1918–1989) proposed the Solow–Swan model, which explains economic growth based on productivity, capital, population growth, and technology. Solow won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1987.

Post World War II and Globalization (Mid to Late 20th Century)

After World War II, the United States became the leading economic power. To prevent another global depression, countries helped rebuild Europe and Japan.

John Kenneth Galbraith (1908–2006) was a strong supporter of active government. In The Affluent Society (1958), he argued that in a society with big businesses, markets don't work like classical economists thought. He believed that large corporations use advertising to create demand for their products, and that economic decisions are often made by a "technostructure" of experts within companies. Galbraith suggested that governments should nationalize military production and public services to reduce inequality.

After the war, economists started combining Keynes's ideas with mathematical models. This led to the "neoclassical synthesis." "Positive economics" became a term for describing economic trends objectively, separate from "normative economic" judgments about what should be.

Paul Samuelson's (1915–2009) book Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947) showed how math could be used to represent economic theory. He assumed that people and firms try to maximize their self-interest and that markets tend towards a balance of prices. His textbook Economics became the most successful economics textbook ever. Samuelson won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1970 for combining math and economics.

Kenneth Arrow (1921–2017) explored the connection between economics and political theory. His "Possibility Theorem" (1951) showed that it's impossible to create a perfect voting system that satisfies all fair conditions. In the 1950s, Arrow and Gérard Debreu (1921–2004) developed the Arrow–Debreu model of how the entire economy reaches a balance.

International Economics: Trade and Development

In 1951, English economist James E. Meade (1907–1995) wrote about international economic policy. He shared the Nobel Prize in 1977.

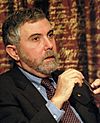

In 1979, American economist Paul Krugman (1953–) developed "New Trade Theory," which explains how increasing returns to scale (when producing more leads to lower costs per unit) and network effects (when a product's value increases as more people use it) affect international trade. He won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2008.

Development Economics: Helping Poorer Countries

In 1954, Sir Arthur Lewis (1915–1991) proposed a model for Development Economics. It explained how capitalism could grow by using a large supply of labor from traditional sectors until wages started to rise. He won the Nobel Prize in 1979.

Simon Kuznets (1901–1985), who introduced the idea of Gross domestic product (GDP) in 1934, found that economic growth initially increases income inequality in poor countries but then decreases it in wealthy countries. He won the Nobel Prize in 1971.

Indian economist Amartya Sen (1933–) focused his work on Development Economics and human rights. He argued that famines happen not just because there's not enough food, but because of unfair ways food is distributed. He believed that the Bengal famine, for example, was caused by an urban economic boom that raised food prices, making it impossible for rural workers to buy food. Sen's work has greatly influenced the "Human Development Report" published by the United Nations Development Programme. He won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1998.

New Economic History (Cliometrics)

In 1958, American economists Alfred H. Conrad (1924–1970) and John R. Meyer (1927–2009) started "New Economic History," also called Cliometrics. This field uses economic theories to re-examine historical data.

Public Choice Theory: Economics of Politics

In 1962, American economists James M. Buchanan (1919–2013) and Gordon Tullock (1922–2014) published The Calculus of Consent. This book revived Public Choice Theory, which applies economic analysis to political decisions. Buchanan won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1986.

Impossible Trinity: International Finance Choices

In 1962–1963, Marcus Fleming (1911–1976) and Robert Mundell (1932–) proposed the "Impossible Trinity." This idea says that a country can only achieve two out of three goals at the same time: a fixed exchange rate, free movement of capital, and an independent monetary policy. Mundell won the Nobel Prize in 1999.

Market for Corporate Control

In 1965, American economist Henry G. Manne (1928–2015) published an article about the "market for corporate control." This theory suggests that changes in stock prices happen faster when insider trading is allowed, and it explains how companies can be bought and sold.

Information Economics: When Information Isn't Perfect

In 1970, George Akerlof (1940–) published "The Market for Lemons," which started the field of Information Economics. This field studies how differences in information between buyers and sellers affect markets. He won the Nobel Prize in 2001.

Joseph E. Stiglitz (1943–) also won the Nobel Prize in 2001 for his work in Information Economics. He has been a critic of global economic institutions. He argues that traditional economic models fail because they don't consider problems that arise when information is not perfect or when certain markets are missing.

Market Design Theory: Designing Better Markets

In 1973, Leonid Hurwicz (1917–2008) started Market (Mechanism) Design Theory. This field, also called Reverse Game Theory, helps people understand when markets work well and when they don't. It helps design better trading systems, rules, and voting methods. He developed this theory with Eric Maskin (1950–) and Roger Myerson (1951–), sharing the Nobel Prize in 2007.

The Laffer Curve and Reaganomics: Taxes and Revenue

In 1974, American economist Arthur Laffer created the Laffer curve. This idea suggests that if tax rates are either 0% or 100%, the government collects no tax revenue. It also implies there's a point where tax revenue is at its highest. This concept was used by U.S. President Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s as part of his economic policies, known as Reaganomics.

Market Regulation: Understanding Market Power

In 1986, French economist Jean Tirole (1953–) began his work on understanding market power and regulation. He won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2014 for his contributions to the theory of industrial organization.

After the 2008 Financial Crisis (21st Century)

The financial crisis of 2008 led to a global recession. This made some economists question the existing economic ideas.

One response was a return to Keynesian solutions. Many policymakers and economists, like Paul Krugman, believed that government action was needed to fix the economy.

Another response was "Austerity" – policies to reduce government debt by cutting spending or raising taxes. Some academic papers supported this, claiming that austerity helped economies recover. However, in 2013, the IMF found errors in one of these papers, showing that the growth of high-debt countries was actually much higher than first thought. This led to renewed calls to end austerity measures.

Images for kids

-

Sir James Steuart (1713–1780)

See also

In Spanish: Historia del pensamiento económico para niños

In Spanish: Historia del pensamiento económico para niños

- Corporate law

- Economic history

- Energy economics

- Index of international trade topics

- Labour law

- List of economics journals

- List of economists

- List of important publications in economics

- Outline of economics

- Perspectives on capitalism

- Timeline of international trade

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |