Jean Bodin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean Bodin

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | c. 1530 Angers, Maine-et-Loire, France

|

| Died | 1596 |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Mercantilism |

|

Main interests

|

Legal philosophy, political philosophy, economy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Quantity theory of money, absolute sovereignty |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

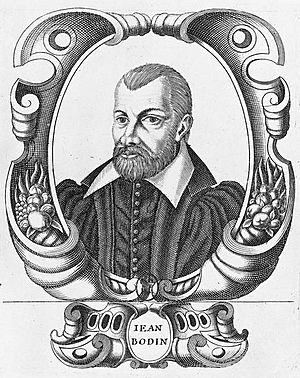

Jean Bodin (French: [ʒɑ̃ bɔdɛ̃]; born around 1530 – died 1596) was an important French thinker. He was a jurist (someone who studies law) and a political philosopher (someone who thinks about how governments should work). Bodin was a member of the Parlement of Paris, which was a high court, and also taught law in Toulouse.

Bodin lived during a time of big changes and conflicts in France, especially the French Wars of Religion. These were fights between Catholics and Protestants. He was a Catholic, but he believed that the Pope should not have power over governments.

He is most famous for his idea of "sovereignty". This means the supreme and independent power of a state. Bodin believed that a strong, central monarchy (a government led by a king or queen) was the best way to keep peace and stop groups from fighting each other.

Towards the end of his life, he wrote a book where people from different religions (Jewish, Muslim, Christian) talked and agreed to live together peacefully. However, this book was not published until much later. He also wrote a lot about demonology, which is the study of demons, during a time when many people believed in witchcraft.

Life of Jean Bodin

Jean Bodin had many different jobs throughout his life. He was a friar, a university teacher, a lawyer, and an adviser to politicians. After a short time as a politician, he spent his later years as a local judge.

Early Years

Bodin was born near Angers, France, around 1530. His family was not rich, but they were comfortable middle-class. He got a good education, possibly at a Carmelite monastery in Angers, where he became a young friar.

Studying in Paris and Toulouse

In 1549, Bodin left the monastery and went to Paris. He studied at the University of Paris and also at a special school focused on humanism, which was a way of thinking that emphasized human values and reason.

Later, in the 1550s, he studied Roman law at the University of Toulouse and also taught there. He was especially interested in comparing different legal systems. Bodin wanted to start a humanist school in Toulouse, but he couldn't get enough support, so he left in 1560.

Wars of Religion and the Politiques

From 1561, Bodin worked as a lawyer for the Parlement of Paris. When the French Wars of Religion started in 1562, he officially confirmed his Catholic faith. He continued to study law and politics in Paris, publishing important books on history and economics.

Bodin became part of a group of thinkers around Prince François d'Alençon. This prince was the youngest son of King Henry II of France. Prince François was a leader of the politiques faction. These were political thinkers who believed in finding practical solutions to end the religious wars, even if it meant being flexible about religious differences.

Working for King Henry III

After Prince François's hopes for the throne ended, Bodin supported the new king, Henry III of France. However, Bodin lost the king's favor in 1576-1577. This happened when Bodin was a delegate for the common people at a meeting called the Estates-General in Blois. He tried to stop a new war against the Huguenots (French Protestants) and also tried to limit the king's ability to raise taxes.

After this, Bodin left political life. He got married in 1576. His wife, Françoise Trouillart, was a widow whose family had legal connections in Laon. Bodin took over some of their legal duties there.

In 1581, Bodin traveled to England with Prince François, who was trying to marry Elizabeth I of England. During this visit, Bodin saw the English Parliament. He also witnessed parts of the trial and execution of Edmund Campion, a Catholic priest. This event led Bodin to write a public letter against using force in religious matters.

Prince François became the Duke of Brabant in 1582. Bodin went with him on a military campaign, which ended badly with a failed attack on Antwerp. Prince François died shortly after in 1584.

Last Years

After King Henry III died in 1589, the Catholic League tried to stop the Protestant Henry of Navarre from becoming king. Bodin first supported the League, thinking they would win quickly.

Jean Bodin died in Laon in 1596 during one of the many plague outbreaks of that time.

Bodin's Important Books

Bodin usually wrote in French, and his works were later translated into Latin. His books covered many topics, including history, economics, politics, demonology, and natural philosophy.

Method for the Easy Knowledge of History

In France, Bodin was known as a historian for his book Methodus ad facilem historiarum cognitionem (1566), which means Method for the easy knowledge of history. He believed that history had three types: human, natural, and divine.

This book was very important for how people wrote history at the time. Bodin emphasized that understanding politics was key to understanding historical writings. He also pointed out that knowing about old legal systems could help create new laws.

Bodin's Methodus was a successful guide for writing detailed history. He rejected the old idea of a "Golden Age" and also the biblical Four Monarchies model, which was unusual for his time.

Economic Ideas: The Reply to Malestroit

Bodin's book Réponse de J. Bodin aux paradoxes de M. de Malestroit (1568) was a response to another writer's ideas. In this book, Bodin gave one of the first detailed explanations of inflation, which is when prices go up over time. Before the 1500s, inflation was not a big problem.

In the 1500s, a lot of silver and gold started coming into Western Europe from places like the Potosí mine in South America. This increase in precious metals caused prices to rise. Bodin was one of the first to notice that this rise in prices was largely due to the large amount of precious metals. He looked at the relationship between the amount of goods available and the amount of money circulating. This discussion helped create the idea of the "quantity theory of money". Bodin also mentioned other reasons for price increases, like a growing population and increased trade.

Theatrum Universae Naturae

The Theatrum Universae Naturae is Bodin's book on natural philosophy, which is the study of nature and the universe. In it, he shared many of his own unique ideas. For example, he thought that eclipses were connected to political events. He also argued against the certainty of some astronomical theories. This work shows how much he believed in the orderly and grand nature of God's creation.

The Six Books of the Republic

Bodin's most famous work is Les Six livres de la République (1576). He wrote it during the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (1572), a terrible event of religious violence. Bodin wanted to find a middle ground in the debates about the best form of government.

His famous definition of sovereignty is: "the absolute and perpetual power of a Republic." He believed that a sovereign ruler is only answerable to God.

The Six Books was an instant success and was printed many times. Bodin later made a revised and expanded Latin translation in 1586. This book helped Bodin become a founder of the politiques group, who eventually helped end the Wars of Religion in France with the Edict of Nantes (1598).

Bodin's ideas in The Six Books about how climate affects people's character were also very influential. He thought that a country's climate shaped its people and, therefore, the best type of government for them. He believed that a hereditary monarchy (where power passes down in a family) was ideal for a country with a moderate climate like France. This ruler should have "sovereign" power, meaning they are not controlled by any other group. However, their power would be somewhat limited by courts and assemblies. Most importantly, the monarch is "responsible only to God," meaning they must be above religious conflicts.

The book quickly became well-known. It was translated into Spanish in 1590 and into English in 1606, titled The Six Bookes of a Common-weale.

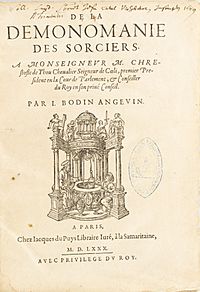

Of the Demon-mania of the Sorcerers

Bodin's major book about sorcery and witchcraft was "Of the Demon-mania of the Sorcerers" (De la démonomanie des sorciers), first published in 1580. It was printed ten times by 1604. In this book, he explained the idea of "pact witchcraft," where people made a deal with the Devil. He believed that evil spirits would try to make judges doubt that witches were real, so they would be seen as sick instead of punished.

Bodin wrote strongly about how witch trials should be handled, arguing against normal legal protections. He believed that if the correct steps were followed, no witch could be wrongly accused. He even said that rumors about sorcerers were almost always true.

This book was very important in the debates about witchcraft. It was translated into German and Latin and was quoted by other writers of the time. One rare copy of the book, signed by Bodin himself, is kept at the University of Southern California.

Bodin's Ideas

Law and Government

Bodin became famous for his ideas on sovereignty, which he saw as a single, complete power that included full law-making abilities. He believed that this power was indivisible. However, he also supported the importance of customary law (laws based on tradition and common practice), saying that Roman law alone was not enough.

Bodin's ideas on political theory helped introduce the modern concept of the "state." He believed that public offices belonged to the community, and those who held them were personally responsible for their actions. He thought that politics should be separate from the church. The ruler's job was to ensure justice and religious worship in the state, following divine and natural law.

Bodin studied the balance between freedom and authority. He did not believe in the separation of powers (like dividing government into executive, legislative, and judicial branches). Instead, he argued for a balance or harmony, where the central power should be above conflicts between different groups.

While Aristotle described six types of states, Bodin only recognized three: monarchy (rule by one), aristocracy (rule by a few), and democracy (rule by the people). He thought that democracy was not a very good form of government.

Bodin saw families as the basic unit and model for the state. He believed that respect for individual freedom and property were signs of an orderly state. He also argued against slavery. For Bodin, religion helped society by encouraging respect for law and government.

On Change and Progress

Bodin praised printing as a greater achievement than anything from ancient times. He is also credited with being one of the first to realize how quickly Europe was changing in the early modern period.

In physics, he was one of the first modern writers to use the idea of physical laws to explain change. In politics, he thought that political revolutions were like astronomical cycles. Bodin believed that governments started as monarchies, then became democratic, and then aristocratic.

Religious Tolerance

Bodin had interesting views on religious tolerance, which were very unusual for his time.

Public Views

In 1576, Bodin argued against using force in religious matters, though he was not successful at the time. He believed that wars should be handled by the state, and religious issues should not interfere with the state's power.

Bodin argued that a state could have several religions within it. This was a very rare idea then, though shared by a few others like Michel de l'Hôpital. He argued in The Six Books that the Trial of the Knights Templar was an unfair persecution, similar to how Jews and medieval groups were treated.

Private Views in the Colloquium

In 1588, Bodin finished a Latin book called Colloquium heptaplomeres de rerum sublimium arcanis abditis (Colloquium of the Seven about Secrets of the Sublime). It was a conversation among seven educated men, each with a different religious or philosophical view: a natural philosopher, a Calvinist, a Muslim, a Roman Catholic, a Lutheran, a Jew, and a skeptic. They all discussed the nature of truth and, in the end, agreed on the basic similarities of their beliefs.

Because of this work, Bodin is often seen as one of the first people in the Western world to support religious tolerance. He believed that true religion would lead to universal agreement, and that the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) agreed on the Old Testament.

The Colloquium was a very popular manuscript that circulated secretly for a long time. Over 100 copies were made. It was not fully published until 1857.

Cultural and Universal History and Geography

Bodin was a polymath, meaning he had knowledge in many different subjects. He was interested in universal history, which he approached from a legal perspective. He was part of a French group of historians who studied ancient times and cultural history.

His book Methodus has been called the first book to offer "a theory of universal history based on a purely secular study of the growth of civilisation." This means he looked at history from a non-religious point of view, focusing on how civilizations developed.

Bodin also used ideas from other cultures and classical authors. He showed little interest in the New World. He influenced later thinkers with his theory that culture spread from the Middle East to Greece and Rome, and then to Northern Europe. He also believed that humanity was becoming more unified through trade and the development of international law.

See also

In Spanish: Jean Bodin para niños

In Spanish: Jean Bodin para niños

- Des Eschelles Manseau

- Jeanne Harvilliers

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |