Austrian school of economics facts for kids

The Austrian School is a way of thinking about economics that focuses on how individuals make choices. It believes that all economic events happen because of the actions and decisions of people. Economists in this school think that economic ideas should come from understanding basic human actions.

This school started in Vienna, Austria, with thinkers like Carl Menger, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, and Friedrich von Wieser. They disagreed with another group of economists, the Historical School, about how to study economics. This disagreement was called Methodenstreit, or "methodology struggle." Today, economists who follow the Austrian School's ideas live in many countries. Some of their early ideas, like the subjective theory of value (how much something is worth to a person) and marginalism (how much value one extra unit of something has), are now part of regular economics.

Since the mid-1900s, many economists have not agreed with the modern Austrian School. This is because the Austrian School often avoids using mathematical models, statistics, and large-scale economic analysis (macroeconomics). However, in the 1970s, the Austrian School gained new interest when Friedrich Hayek shared the 1974 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

Contents

History of the Austrian School

How the Name Started

The name "Austrian School" was actually given by their rivals, the German Historical School. This happened during a debate in the late 1800s called the Methodenstreit. The Germans used the name to suggest the Austrians were old-fashioned and local. However, the Austrian economists liked the name and kept it. In 1883, Carl Menger wrote a book that challenged the Historical School's methods. A leader of the Historical School, Gustav von Schmoller, gave it a bad review and used the term "Austrian School."

The First Thinkers

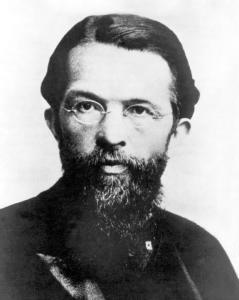

The Austrian School began in Vienna, Austrian Empire. Carl Menger's 1871 book, Principles of Economics, is seen as the start of the school. His book was one of the first to explain the idea of marginal utility. This means that the value of something depends on how much satisfaction you get from one more unit of it. The Austrian School was a key part of the "marginalist revolution" of the 1870s, which brought in the idea that economics should focus on individual choices and values.

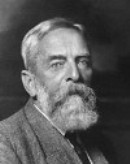

Menger's ideas were followed by those of Eugen Böhm von Bawerk and Friedrich von Wieser. These three are known as the "first wave" of the Austrian School. Böhm-Bawerk also wrote strong criticisms of Karl Marx's ideas.

Early 1900s Developments

In the United States, Frank Albert Fetter was a leader of Austrian ideas. Many important Austrian economists studied at the University of Vienna in the 1920s. They also attended private meetings led by Ludwig von Mises. These students included Gottfried Haberler, Friedrich Hayek, Fritz Machlup, and Oskar Morgenstern.

Mid to Late 1900s

By the mid-1930s, many of the early Austrian ideas were accepted into mainstream economics. As Fritz Machlup said, "the greatest success of a school is that it stops existing because its fundamental teachings have become parts of the general body of commonly accepted thought." However, by the mid-1900s, Austrian economics became less popular with mainstream economists. This was because it did not use mathematical models or statistical methods.

After the 1940s, Austrian economics saw some different paths. One group, following Mises, believed that standard economic methods were wrong. Another group, following Friedrich Hayek, accepted some of the standard methods and was more open to government involvement in the economy. Henry Hazlitt was a writer who promoted Austrian ideas from the 1930s to the 1980s. His book Economics in One Lesson (1946) sold over a million copies.

The Austrian School's reputation grew again in the late 1900s. This was partly due to the work of Israel Kirzner and Ludwig Lachmann at New York University. Also, Friedrich Hayek winning the Nobel Prize in 1974 brought more attention to their ideas.

Different Views Today

Today, there are some different views within the Austrian School. Some economists, like Hans-Hermann Hoppe and Walter Block, see Murray Rothbard as a key leader. They believe that the Austrian School should strongly support individual freedom and limited government. They sometimes disagree with Hayek's ideas.

Other economists, like Peter Boettke and Steven Horwitz, are more aligned with Hayek's views. They are often found at universities like George Mason University. The Mises-Rothbard group is often linked with the Mises Institute. Despite these differences, both groups contribute to Austrian economic thought.

How Austrian Ideas Spread

Many ideas from the "first wave" Austrian economists are now part of regular economics. These include Carl Menger's ideas on marginal utility, Friedrich von Wieser's ideas on opportunity cost, and Eugen Böhm von Bawerk's ideas on how people value things over time.

Even former American Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said that the founders of the Austrian School had a "profound" effect on how many economists think. Today, universities like George Mason University, New York University, and King Juan Carlos University in Spain have strong Austrian economics programs. Organizations like the Mises Institute and the Cato Institute also promote Austrian ideas.

How Austrian Economists Study Things

The Austrian School believes that all economic events come from the personal choices of individuals. This includes their knowledge, how they view time, and what they expect for the future. Austrians try to understand the economy by looking at how individual choices affect society. This is called methodological individualism. It's different from other economic schools that look at large groups or total numbers.

In the 1900s, Ludwig von Mises developed his own approach called "praxeology." In his 1949 book, Human Action, Mises said that praxeology could be used to figure out economic truths just by thinking logically, without needing to look at real-world data or statistics. He believed that economic conclusions could not come from experiments or statistical analysis.

However, not all Austrian thinkers fully agree with Mises's strict approach. For example, Friedrich Hayek and Fritz Machlup were more open to other methods. Ludwig Lachmann also preferred a different "interpretive method."

Some modern Austrian economists also use models and math in their work. For example, Steven Horwitz argued that Austrian ideas can be shown using microeconomics. Roger Garrison says that Austrian macroeconomic theory can be explained with diagrams.

Main Ideas of Austrian Economics

In 1981, Fritz Machlup listed the main ideas of Austrian economic thinking:

- Methodological individualism: To understand economic events, we must look at what individuals do. Groups don't act; only people do.

- Methodological subjectivism: Economic events are explained by the choices individuals make based on what they know or believe.

- Tastes and preferences: What people like and want affects the demand for goods and services. This influences their prices.

- Opportunity costs: The cost of doing something is what you give up by not choosing the next best option. If you use resources for one thing, you can't use them for another.

- Marginalism: In economics, values, costs, and profits are determined by the importance of the very last unit added or taken away.

- Time structure of production and consumption: Decisions about saving show how people prefer to consume now versus in the future. Investments are made to get more output later, often through longer production processes.

Machlup also added two more ideas from the Mises branch of Austrian economics:

- Consumer sovereignty: Consumers have a big influence on what is produced through their demand and the prices in free markets. This is important and can only happen if the government doesn't interfere with markets.

- Political individualism: People can only have true political and moral freedom if they have full economic freedom. Limiting economic freedom can lead to the government controlling more aspects of life, which can destroy individual liberties.

Important Ideas from the Austrian School

Opportunity Cost

The idea of opportunity cost was first clearly explained by the Austrian economist Friedrich von Wieser in the late 1800s. Opportunity cost is the value of the best thing you give up when you choose something else. For example, if you choose to spend your money on a video game, the opportunity cost might be the new book you could have bought instead. It's a key idea in economics and shows the basic link between having limited resources and making choices.

Capital and Interest

The Austrian theory of capital and interest was developed by Eugen Böhm von Bawerk. He said that interest rates and profits are shaped by how much people want goods and services, and by how much people prefer to have things now versus later (called "time preference").

Inflation

In Ludwig von Mises's view, inflation means an increase in the amount of money in circulation. This happens when the money supply grows faster than the need for money, causing money to lose its value.

Friedrich Hayek explained that increasing the money supply to boost jobs only works for a short time. This is because there's a delay between when money increases and when prices go up. He argued that a small, steady inflation won't help and will eventually lead to bigger inflation.

Economic Calculation Problem

The economic calculation problem is a criticism of planned economies. It was first mentioned by Max Weber and later developed by Mises and Hayek. The problem states that without prices set by markets, it's impossible for central planners to know how to use resources in the best way. This makes planned economies very inefficient.

Austrian theory highlights how markets organize themselves. Hayek said that market prices carry information that no single person knows completely. This information helps decide how resources are used. Because socialist systems don't have individual incentives or market prices, Hayek argued that socialist planners lack the knowledge to make good decisions. This idea was a big part of the "socialist calculation debate" in the 1920s and 1930s.

Mises argued in 1920 that prices in socialist economies would be flawed. If the government owned everything, there would be no real prices for things like factories or machines because they wouldn't be traded in a market. Without these prices, central planners wouldn't know how to use resources efficiently. He concluded that "rational economic activity is impossible in a socialist commonwealth."

Business Cycles

The Austrian theory of the business cycle (ABCT) explains why economies go through "booms" (growth) and "busts" (recessions). Ludwig von Mises suggested that banks, by lending money at very low interest rates, encourage businesses to invest in projects that aren't really profitable. This creates an artificial "boom." Mises called this a "malinvestment" – bad investments – which eventually leads to a "bust" or recession.

Mises believed that when the government or central banks change the money supply and credit, it throws off the balance between saving and investing. This leads to bad investments that can't last. The economy then has to correct itself through a recession. Austrian economists believe the government should let the free market handle money and banking. This would prevent booms and busts, leading to more stable economic growth.

A Keynesian economist might suggest government spending during a recession. However, Austrian theory argues that government attempts to "fine-tune" the economy by changing the money supply are actually the cause of business cycles. Austrian economist Thomas Woods argues that production, not consumption, is what makes a country rich.

Central Banks

Ludwig von Mises thought that central banks allow regular banks to offer loans at artificially low interest rates. This causes too much bank credit and prevents the economy from correcting itself. He supported a gold standard to limit the growth of money. Friedrich Hayek had a slightly different view, focusing on regulating the banking sector through strong central banking.

Criticisms of the Austrian School

General Criticisms

Many mainstream economists don't agree with modern Austrian economics. They argue that Austrian economists are too against using math and statistics in their studies. Austrians believe that human behavior is too complex and changes too much for mathematical models to always be true. However, they do support using math to understand consumer choices in business and finance.

Economist Paul Krugman has said that Austrians might miss problems in their own ideas because they don't use "explicit models."

Jeffrey Sachs argues that countries with higher taxes and more social welfare spending often do better economically. He believes that Friedrich Hayek was wrong to say that high government spending harms an economy. Instead, Sachs thinks a generous welfare state leads to fairness and economic equality.

Criticisms of Their Methods

Critics often say that Austrian economics lacks scientific strictness. They argue that it rejects scientific methods and using real-world data to understand economic behavior. Some economists describe the Austrian method as being based on pure logic rather than evidence.

Economist Mark Blaug has criticized the Austrian focus on individual actions. He says it would mean rejecting almost all of macroeconomics, which looks at the economy as a whole.

Thomas Mayer says that Austrians reject the scientific method, which involves creating ideas that can be tested with evidence.

Criticisms of Business Cycle Theory

Mainstream economic research often finds that the Austrian business cycle theory doesn't match real-world evidence. Famous economists like Milton Friedman and Paul Krugman have said they believe the theory is incorrect.

Why Some Disagree

Some economists argue that the Austrian business cycle theory suggests bankers and investors act irrationally. This is because the theory says investors are repeatedly tricked by low interest rates into making bad investments. Milton Friedman also disagreed with the policy ideas from the theory. He said that in the 1930s, Austrian economists like Hayek believed the economy should just be left to collapse and fix itself. Friedman thought this "do-nothing" approach caused harm.

Evidence Against the Theory

In 1969, Milton Friedman studied business cycles in the United States. He found no clear link between how big an economic expansion was and how big the following contraction was. This went against theories, like the Austrian one, that rely on such a connection. He found the same results again in 1993.

See Also

In Spanish: Escuela austriaca para niños

In Spanish: Escuela austriaca para niños

- Carl Menger

- Chicago school of economics

- Criticism of the Federal Reserve

- Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk

- Friedrich Hayek

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe

- Henry Hazlitt

- Israel Kirzner

- List of Austrian intellectual traditions

- List of Austrian School economists

- Ludwig von Mises

- New institutional economics

- Perspectives on capitalism by school of thought

- School of Salamanca

- Gold standard

|

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |