January Uprising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids January Uprising |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Polish-Russian wars | |||||||

Poland - The Year 1863, by Jan Matejko, 1864. This painting shows what happened after the uprising failed. People are being sent to Siberia. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| At least 220,000 by June 1864. | Around 200,000 over the course of the uprising. Around 20 men of the Garibaldi Legion. | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Russian estimates: 4,500 killed, wounded and missing Polish estimates: 10,000 killed, wounded and missing |

Polish estimates: 10,000 to 20,000 Russian estimates: 30,000 (22,000 killed and wounded, 7,000 captured) |

||||||

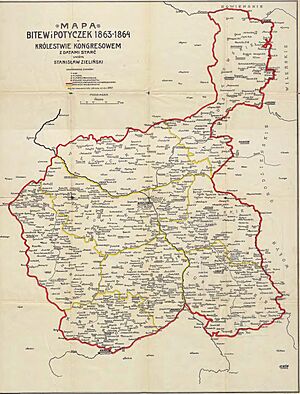

The January Uprising was a big rebellion that happened mainly in Congress Poland, which was then controlled by the Russian Empire. Its main goal was to end Russian rule and make Poland independent again. The uprising started on January 22, 1863, and lasted until the last rebels were caught by Russian forces in 1864.

This was the longest rebellion in Poland during a time when it was divided by other countries. It involved people from all parts of society. The uprising had a huge impact on how other countries saw Poland. It also changed Polish society and its future development.

Contents

Why Did the Uprising Happen?

Many things led to the uprising in early 1863. Polish nobles and city people wanted to regain some freedom they had before a previous uprising in 1830. Young people were also inspired by Italy's success in gaining independence.

Russia had been weakened by the Crimean War. This led to a more relaxed approach in its own country. This encouraged Poland's secret National Government to plan a strike against the Russian rulers. However, they did not expect Aleksander Wielopolski, a pro-Russian leader in Poland. He tried to stop the Polish national movement by forcing young Polish activists into the Imperial Russian Army for 20 years of service. This decision, made in January 1863, actually triggered the January Uprising, which was exactly what Wielopolski wanted to avoid.

The rebellion started with young Polish men who were forced into the army. Soon, high-ranking Polish-Lithuanian officers and politicians joined them. The rebels were not well organized. They were also greatly outnumbered and did not have enough support from other countries. This forced them to use risky guerrilla warfare tactics.

The Russian response was quick and harsh. Many people were executed or sent away to Siberia. This made many Poles give up fighting. Also, Tsar Alexander II made a sudden decision in 1864 to end serfdom in Poland. This meant peasants were no longer tied to the land. This change hurt the wealthy landowners and the economy. Because of this, educated Poles started focusing on "organic work". This meant improving their economy and culture instead of fighting.

Life Under Russian Rule

Even though Russia lost the Crimean War and was weaker, Tsar Alexander II warned in 1856 against giving Poland more freedom. There were two main groups of thought among people in the Kingdom of Poland. One group, called the Whites, were mostly wealthy landowners and thinkers. They wanted to peacefully return to the way things were before 1830.

The other group, called the Reds, was a democratic movement. It included peasants, workers, and some religious leaders. Both groups faced the problem of what to do about the peasants. Landowners wanted to end serfdom, but only if they received money for it. The democratic movement believed that getting rid of Russian rule depended on freeing the peasants without any conditions.

As the democratic groups organized protests in 1860, secret resistance groups started forming among young educated people. The first bloodshed happened in Warsaw in February 1861. The Russian Army attacked a protest in Castle Square. Five people died.

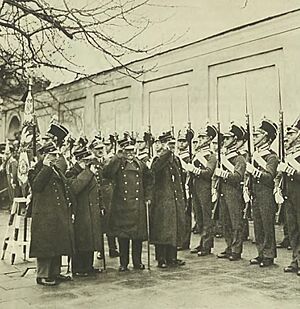

Fearing more unrest, Alexander II agreed to consider changes in government. He appointed Aleksander Wielopolski to lead a group looking into religious practices and public education. He also announced a State Council and self-governance for towns. But these changes did not stop more protests. On April 8, 200 people were killed and 500 wounded by Russian fire. Martial law was put in place in Warsaw. Organizers were harshly punished and sent deep into Russia.

In Vilna alone, 116 protests happened in 1861. That autumn, Russians declared a state of emergency in several areas.

Planning the Uprising

These events made the resistance groups stronger. Future leaders of the uprising met secretly in cities like St. Petersburg, Warsaw, and Paris. Two main groups came from these meetings. By October 1861, the "Movement Committee" was formed. Then, in June 1862, the Central National Committee (CNC) was created. Its leaders included Stefan Bobrowski and Jarosław Dąbrowski. This group worked to create a new secret Polish state.

The CNC had planned the uprising for spring 1863 at the earliest. But Wielopolski's decision to start forcing young men into the Russian Army in mid-January pushed them to act sooner. They called for the uprising on the night of January 22–23, 1863.

How the Uprising Began

The uprising began when Europe was mostly peaceful. Even though many people supported the Poles, countries like France, Britain, and Austria did not want to start a new international conflict. The rebel leaders did not have enough weapons for the young men hiding in forests to avoid being forced into the Russian Army.

At first, about 10,000 men joined the rebellion. These volunteers were mostly city workers and clerks. But there were also many younger sons of poorer nobles and some lower-ranking priests. The Russian government had an army of 90,000 men in Poland at the start.

It seemed like the rebellion might be quickly crushed. But the CNC's temporary government issued a statement. It said that "all sons of Poland are free and equal citizens." It also declared that land worked by peasants should become their own property. Landowners would be paid for this land by the state.

The temporary government tried its best to send supplies to the unarmed volunteers. In February, they fought in eighty bloody battles with the Russians. The CNC also asked for help from Western European countries. This request was met with support from places like Norway and Portugal. Even the Confederate States of America felt sympathy for the Polish-Lithuanian rebels. Italian, French, and Hungarian officers came to help. By late spring and early summer of 1863, there were 35,000 Poles fighting against a Russian Army of 145,000 in Poland.

The Uprising Spreads

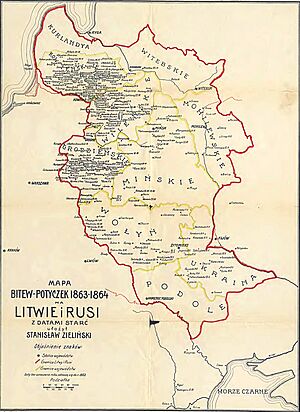

On February 1, 1863, the uprising also started in the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. By April and May, it had spread to parts of Latvia, Belarus, and Ukraine. Volunteers, weapons, and supplies started coming in from Galicia (controlled by Austria) and from the Prussian Partition. Volunteers also arrived from Italy, Hungary, France, and even Russia.

The biggest problem was that peasants did not join the fight much. Even though the CNC promised them freedom, they were not ready to rebel. Only in areas where Polish units were strong did some farm workers join the uprising.

The Secret Polish State

The secret Polish state was led by the Rada Narodowa (RN), or National Council. This council oversaw the civil and military groups on the ground. It was a "virtual coalition government" made up of the Reds and the Whites. Its leaders included Zygmunt Sierakowski, Antanas Mackevičius, and Konstanty Kalinowski. The latter two supported their Polish partners and followed common policies.

The RN's diplomatic efforts were based in Paris, led by Wladyslaw Czartoryski. The fighting in the former Commonwealth of Two Nations surprised Western European countries. But public opinion was sympathetic to the rebels. Paris, London, Vienna, and St. Petersburg realized that this crisis could turn into a larger international war. Russian diplomats, however, saw the uprising as an internal matter.

International Reactions

The discovery of the Alvensleben Convention made the uprising an international issue. This agreement, signed on February 8, 1863, by Prussia and Russia, was to work together to stop the Poles. This allowed Western powers to get involved in diplomacy.

Napoleon III of France, who already supported Poland, wanted to protect his border with Prussia. He tried to start a war with Prussia and also sought an alliance with Austria. The United Kingdom, however, wanted to prevent a war between France and Prussia. It also wanted to stop Austria from allying with France. Austria was competing with Prussia for leadership of the German territories. But it refused France's offers for an alliance.

There was no talk of military help for the Poles, even with Napoleon's support for the uprising. France, the United Kingdom, and Austria agreed to a diplomatic effort to defend Polish rights. In April, they sent diplomatic notes that were meant to be persuasive. The Polish RN hoped that the uprising would eventually force Western powers to intervene with military action. The Poles argued that lasting peace in Europe depended on Poland becoming an independent state again.

Russia was willing to talk but firmly rejected any Western right to military action. In June 1863, Western powers repeated their conditions: an amnesty for the rebels, a national representative body, more freedom for the Kingdom, a meeting of the countries that signed the Congress of Vienna (1815) agreement, and a ceasefire. This was far less than what the uprising's leaders expected. Although concerned by the threat of war, Alexander II felt secure with his people's support and rejected the proposals. France and Britain were insulted but did not take further action. This allowed Russia to continue and finally break off negotiations in September 1863.

What Happened After the Uprising?

Foreign countries trying to help Poland actually hurt the cause. It took attention away from Polish unity and highlighted its internal divisions. It also upset Austria, which had been neutral and allowed Polish activities in Galicia. It also angered radical groups in Russia who had supported the uprising as a social movement. This made the Russian government suppress the rebellion even more brutally.

Many thousands died in battle. Also, 128 men were executed under Mikhail Muravyov. About 9,423 men and women were sent away to Siberia. Some historians say the number was as high as 80,000, making it the largest deportation in Russian history. Whole villages and towns were burned down. All economic and social activities stopped. The nobles lost their wealth through property seizure and high taxes.

The actions of Russian troops were so harsh that they were condemned across Europe. Count Fyodor Berg, the new governor, used severe measures against the people. He increased efforts to make Poles more Russian, trying to erase Polish traditions and culture.

Social Differences and the Uprising

About 60% of the rebels were from wealthy landowning families. In Lithuania and Belarus, it was about 50%, and in Ukraine, about 75%. Records show that 95% of those punished for joining the uprising were Catholic. This matched the general number of participants.

The Polish nobles tried to get Rus (Ruthenian) peasants to join. But very few participated in the January Uprising. In some cases, they even helped the Russian forces catch rebels. This is seen as one of the main reasons the uprising failed.

In the first 24 hours of the uprising, weapons stores were raided. Many Russian officials were killed on sight. On February 2, 1863, the first major battle happened. Lithuanian peasants, mostly armed with scythes, fought Russian soldiers near Marijampolė. The unprepared peasants suffered a tragic loss of life. While there was still hope for a short war, rebel groups joined together and recruited new volunteers.

The End of the Fight

The temporary government had hoped for a rebellion in Russia itself, where people were unhappy with the government. It also counted on help from Napoleon III. This was especially true after Prussia signed the Alvensleben Convention with Russia. This agreement offered help in stopping the Polish uprising.

This step by Otto von Bismarck led to protests from several governments. It angered the different nations of the former Commonwealth. This turned a small uprising into another "national war" against Russia. Encouraged by Napoleon III's promises, all parts of the former Commonwealth joined the fight. Also, all citizens holding positions in the Russian government, including the Archbishop of Warsaw, resigned. They pledged loyalty to the new Polish Government.

It was only after Polish General Romuald Traugutt took charge on October 17, 1863, that the struggle could continue. He tried to unite all social classes under one national flag. He reorganized the forces for an attack in spring 1864, hoping for a Europe-wide war. On December 27, 1863, he made a decree that gave peasants the land they worked. The landowners would be paid by the state after the uprising succeeded. Traugutt called on all Poles to fight Russian rule for a new Polish state.

The response was not strong because the policy came too late. The Russian government had already started giving peasants generous land parcels. Peasants who received land did not join the Polish rebels or support them much.

Fighting continued through the winter of 1863–1864 near the Galician border, where help was still coming from. In late December, General Michał Heydenreich's unit was defeated. The strongest resistance continued in the Świętokrzyskie Mountains. Here, General Józef Hauke-Bosak bravely took several cities from the much larger Russian forces. However, he also suffered a crushing defeat on February 21, 1864. This signaled the end of the armed struggle.

On February 29, Austria declared martial law. On March 2, the Russian authorities ended serfdom in Poland. Both events stopped Traugutt's plan to grow the uprising with a general call to arms and help from Galicia. In April 1864, Napoleon III gave up on the Polish cause. Władysław Czartoryski wrote to Traugutt: "We are alone, and alone we shall remain."

Arrests removed key leaders of the secret Polish state. Those who felt threatened fled abroad. Traugutt was captured on the night of April 10. He and the last four members of the National Council were imprisoned. They were executed by hanging on August 5 at the Warsaw Citadel. This marked the symbolic end of the Uprising. Only Aleksander Waszkowski, the head of the Warsaw uprising, avoided capture until December 1864. He was also caught in February 1865. The war involved 650 battles and skirmishes. About 25,000 Polish and other rebels were killed. The uprising lasted 18 months. The rebellion continued in some areas until spring 1865.

Decades of Reprisals

After the uprising failed, very harsh punishments followed. Russian records say 396 people were executed. About 18,672 were sent to Siberia. Many men and women were sent to distant parts of Russia. In total, over 60,000 people were imprisoned and exiled from Poland.

The ending of serfdom in early 1864 was meant to ruin the wealthy landowners. The Russian government took 1,660 estates in Poland and 1,794 in Lithuania. A 10% income tax was put on all estates as a war payment. This tax was lowered to 5% in 1869. This was the only time peasants paid the market price for their land. All land taken from Polish peasants since 1864 was returned without payment. Former serfs could only sell land to other peasants, not to nobles.

All these actions were to punish the nobles for their role in the uprisings of 1830 and 1863. The Russian government also gave peasants forests, pastures, and other rights. These caused constant problems between landowners and peasants for decades. They also slowed down economic growth. The government took over all church lands and money. It also closed monasteries and convents.

Except for religious lessons, all teaching in schools had to be in Russian. Russian also became the official language of the country. It had to be used in all government offices. All signs of Polish freedom were removed. The Kingdom was divided into ten provinces. Each had a Russian military governor controlled by the Governor-General in Warsaw. All former Polish government workers lost their jobs and were replaced by Russian officials.

Lasting Impact

These efforts to erase Polish culture were only partly successful. In 1905, 41 years after Russia crushed the uprising, the next generation of Poles rebelled again in the Łódź insurrection, which also failed.

The January Uprising was one of many Polish uprisings over centuries. After it ended, two new movements began. These shaped Polish politics for the next century. One was led by Józef Piłsudski, who started the Polish Socialist Party. The other was led by Roman Dmowski, who created the National Democracy movement. This group wanted national freedom and to reverse the forced Russification and Germanization of Poles.

Key People in the Uprising

- Francišak Bahuševič (1840–1900): A Belarusian poet and writer.

- Stanisław Brzóska (1832–1865): A Polish priest and commander at the end of the uprising.

- Saint Albert Chmielowski (1845–1916): Founder of the Albertine Brothers and Sisters.

- Jarosław Dąbrowski (1836–1871): An officer in the Russian Army who became a left-wing leader of the "secret committee." He later fought for the Paris Commune.

- Wincenty Kalinowski (1838–1864): A leader of the Lithuanian national revival and the January Uprising in Lithuania.

- Saint Raphael Kalinowski (1835–1907): Born Joseph Kalinowski, he left the Russian Army to become Minister of War for the Polish rebels. He was arrested and sentenced to death, but this was changed to 10 years in Siberia.

- Apollo Korzeniowski (1820–1869): A Polish playwright and the father of famous writer Joseph Conrad.

- Marian Langiewicz (1827–1887): A military commander of the uprising.

- Antanas Mackevičius (1828–1863): A Lithuanian priest who organized about 250 men. He was captured and executed.

- Ludwik Mierosławski (1814–1878): A veteran of earlier uprisings, a general, and a writer.

- Władysław Niegolewski (1819–1885): A liberal Polish politician and rebel in earlier uprisings and the January Uprising.

- Francesco Nullo (1826–1863): An Italian general who led the Garibaldi Legion. He died in battle.

- Bolesław Prus (1847–1912): A leading Polish writer of historical novels.

- Anna Henryka Pustowójtówna (1838–1881): Also known as "Michał Smok," she was an assistant to Marian Langiewicz. She later took part in the Paris Commune.

- François Rochebrune (1830–1870): A French officer who formed and led a Polish rebel unit called the Zouaves of Death.

- Aleksander Sochaczewski (1843–1923): A Polish painter.

- Romuald Traugutt (1826–1864): A former Russian Army officer who became a general and leader of the uprising. He was executed by the Russians.

Uprising in Art and Stories

The events and people of the uprising inspired many Polish painters. These included Artur Grottger, Juliusz Kossak, and Michał Elwiro Andriolli. The uprising also marked a shift in Polish art and thought.

- The Polish poet Cyprian Norwid wrote a famous poem, "Chopin's Piano." It describes Russian soldiers throwing the composer's piano out of a Warsaw apartment during the uprising. Chopin had left Poland before the 1830 uprising.

- Eliza Orzeszkowa, a leading Polish writer, wrote Nad Niemnem. This novel is set around the city of Grodno after the 1863 January Uprising.

- Józef Jarzębowski collected stories from unknown people who lived through the uprising in his book Mówią Ludzie Roku 1863: Antologia nieznanych i małoznanych Głosów Ludzi współczesnych (Voices from 1863).

- In an early draft of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas by Jules Verne, Captain Nemo was a Polish nobleman. His family was brutally murdered by the Russians during the January 1863 Uprising. However, this was changed in the final book because France had recently allied with Russia.

- In Guy de Maupassant's novel Pierre et Jean, one character is an old Polish chemist. He is said to have come to France after the bloody events in his homeland, likely referring to the January Uprising.

Gallery

-

Chapel in Vilnius, built to remember the crushing of the 1863 January Uprising. Picture by Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii.

See also

- Stefan Brykczyński

- Menotti Garibaldi

- Zouaves of Death

- Insurgence

- Polish uprisings

- Sybirak

- The Prisoners

- International Workingmen's Association

- Lapinski expedition