Roman Dmowski facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Roman Dmowski

|

|

|---|---|

Dmowski c. 1919

|

|

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 27 October 1923 – 14 December 1923 |

|

| President | Stanisław Wojciechowski |

| Prime Minister | Wincenty Witos |

| Preceded by | Marian Seyda |

| Succeeded by | Karol Bertoni (Acting) |

| Member of the State Duma of the Russian Empire | |

| In office 1907–1909 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 August 1864 Kamionek, Kingdom of Poland |

| Died | 2 January 1939 (aged 74) Drozdowo, Poland |

| Resting place | Bródno Cemetery, Warsaw |

| Political party |

|

| Alma mater | University of Warsaw |

| Signature | |

Roman Stanisław Dmowski (born August 9, 1864 – died January 2, 1939) was an important Polish politician and statesman. He helped create and was the main thinker behind the National Democracy political movement, also known as "Endecja."

Dmowski believed that the biggest threat to Polish culture was the "Germanization" (making things German) of Polish lands controlled by the German Empire. He thought Poland should work with the Russian Empire to regain its independence peacefully. He also supported policies that helped the Polish middle class.

During World War I, Dmowski was a key voice for Polish independence among the Allied countries in Paris. He played a big part in bringing Poland back as an independent country after the war. For most of his life, he was a major opponent of another Polish leader, Józef Piłsudski. Piłsudski wanted a Poland made up of many different ethnic groups, while Dmowski wanted a Poland that was mainly Polish-speaking and Roman Catholic.

Dmowski was only a Minister of Foreign Affairs for a short time in 1923. However, he was one of the most influential Polish thinkers and politicians of his era. He is often called "the father of Polish nationalism."

Contents

Early Life and Education

Roman Dmowski was born on August 9, 1864, in Kamionek, near Warsaw. This area was part of the Kingdom of Poland, which later became part of the Russian Empire. His father worked in road construction and later became a business owner.

Dmowski went to schools in Warsaw and studied biology and zoology at University of Warsaw. He graduated in 1891. As a student, he joined the Polish Youth Association "Zet". He worked against socialist groups and joined the Liga Polska (Polish League) in 1889. A main idea of the League was Polskość (Polishness), meaning loyalty to Poland, not to the countries that had divided Poland.

He also helped organize a student protest on the 100th anniversary of the Polish Constitution. For this, Russian authorities put him in prison for five months. He was then sent away to Latvia. After 1890, he also became a writer, publishing political articles.

Founding Political Groups

In 1893, Dmowski helped start the National League and became its first leader. He believed there should be only one Polish national identity. This idea meant that minority groups, like Jews, were not included in his vision of the Polish nation.

In 1893, he was exiled again. He went to Lemberg (now Lviv, Ukraine), where he started a new magazine called Przegląd Wszechpolski (All-Polish Review). In 1897, he co-founded the National-Democratic Party, known as "Endecja." This party was meant to unite Poles who shared Dmowski's views.

In 1903, he published a book called Myśli nowoczesnego Polaka (Thoughts of a Modern Pole). This book was one of the first nationalist manifestos in Europe. In it, Dmowski criticized the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth for being too tolerant of minorities. He also rejected liberalism and socialism, saying they put individuals above the nation. Dmowski believed Poland needed a strong sense of national unity.

Political Actions in Russian Poland

In 1905, Dmowski moved back to Warsaw, in the Russian part of Poland. During the Russian Revolution of 1905, Dmowski supported working with the Russian authorities. He saw the Tsar's promise of greater Polish freedom as a step towards independence.

During a revolt in Łódź in June 1905, Dmowski's party (Endecja) opposed the uprising led by Piłsudski's Polish Socialist Party (PPS). A small civil war happened between the two groups. Dmowski believed that fighting a guerrilla war was not practical. He saw the Russian legislative assembly (Duma) as a way to improve Poland's situation within the Russian Empire.

Dmowski was elected as a representative to the Second and Third Dumas (starting in 1907). He led the Polish group there. He was seen as a conservative. He believed that Russian attempts to make Poles more Russian would fail, but German attempts to make Poles more German would succeed. He wrote about these ideas in his 1908 book Niemcy, Rosja i kwestia Polska (Germany, Russia and the Polish Cause).

In 1912, Dmowski lost an election to a socialist politician who won with Jewish support. Dmowski felt this was a personal insult. In response, he organized a successful boycott of Jewish businesses across much of Poland.

World War I and Polish Independence

In 1914, Dmowski welcomed Russia's promise of greater freedom for Polish lands after the war. He hoped that Polish areas controlled by Germany and Austria-Hungary would join a united Poland. Dmowski's pro-Russian and anti-German efforts helped his standing as an important Polish political figure internationally. In November 1914, he joined the Polish National Committee.

In 1915, Dmowski became convinced that Russia would lose the war. He decided to go to Western Allied capitals to promote Polish independence. He was very successful in France and made a good impression. He also gave lectures at Cambridge University, which led to him receiving an honorary doctorate.

In August 1917, in Paris, he created a new Polish National Committee to help rebuild a Polish state. He also published Problems of Central and Eastern Europe. He strongly criticized Austria-Hungary and pushed for new Slavic states to be formed from its lands. He opposed those Poles who wanted to ally with Germany and Austria-Hungary.

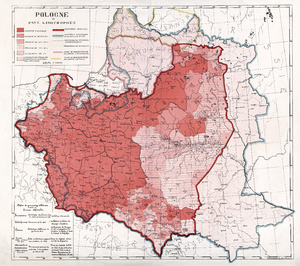

In 1917, Dmowski drew up a plan for the borders of a new Polish state. It included areas like Greater Poland, Pomerania with Gdańsk, and Upper Silesia. In September 1917, the French recognized Dmowski's National Committee as the official government of Poland. The British and Americans also recognized it a year later, though they were less enthusiastic about his large territorial claims.

American President Woodrow Wilson was concerned about Dmowski's extensive demands. Wilson noted that Dmowski presented a map claiming "a large part of the earth." Some diplomats found Dmowski difficult to work with due to his strong opinions and persistence.

Dmowski also faced criticism for his antisemitic remarks. He refused to include any Polish Jews on the National Committee, even when Ignacy Paderewski supported it. This led to American and British Jewish organizations campaigning against recognizing his committee.

After World War I

After World War I, two groups claimed to be the government of Poland: Dmowski's in Paris and Piłsudski's in Warsaw. To solve this, the composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski convinced them to work together. Piłsudski controlled Poland, but the Allies did not trust him because he had fought with the Austrians. Dmowski, however, could get arms from the Allies for the new Polish Army.

Paderewski helped them agree: Dmowski and Paderewski would represent Poland at the Paris Peace Conference, while Piłsudski would be the temporary president of Poland. Some of Dmowski's supporters did not like this agreement and tried a failed coup against Piłsudski in January 1919.

As a Polish delegate at the Paris Peace Conference, Dmowski greatly influenced the decisions about Poland's borders. In January 1919, he gave a five-hour presentation to the Allies' Supreme War Council, which was described as brilliant. He argued for Polish territories with Polish-speaking majorities that had been taken by Prussia. He also wanted some lands beyond Poland's old borders, like southern East Prussia and Upper Silesia, for economic reasons.

Dmowski also wanted to send the "Blue Army" (loyal to him) to Poland through Danzig (now Gdańsk). This idea was opposed by Germany, Britain, and America. Eventually, the Blue Army was sent to Poland by land in April 1919.

Regarding Lithuania, Dmowski believed Lithuanians did not have a strong national identity. He claimed areas of Lithuania with Polish majorities or minorities, saying Poles would bring a civilizing influence. He wanted northern Lithuania, with a solid Lithuanian majority, to be independent. His initial plans for Lithuania involved it being an autonomous part of a Polish state.

For East Galicia, Dmowski claimed that the local Ukrainians could not rule themselves and needed Polish leadership. He also wanted the oil fields there. The Polish-Ukrainian War ultimately decided that Galicia would be part of Poland.

Dmowski always opposed Piłsudski. Dmowski wanted a "national state" where citizens spoke Polish and were Roman Catholic. Piłsudski wanted a multinational federation, like the old Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Dmowski believed that many ethnic minorities would weaken Poland. At the Paris Peace Conference, he strongly argued against the Minority Rights Treaty forced on Poland by the Allies.

Dmowski was disappointed with the Treaty of Versailles. He disliked the Minority Rights Treaty and wanted the German-Polish border to be further west. He blamed these disappointments on what he called an "international Jewish conspiracy." He believed British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was influenced by German-Jewish financiers to give Poland unfavorable borders.

Later Life and Views

Dmowski was a representative in the 1919 Legislative Sejm, but he attended only one session. He felt the Sejm was too chaotic. He reorganized his party into the Popular National Union. During the Polish-Soviet War, he was part of the Council of National Defense and criticized Piłsudski's policies. After the war, Poland's eastern borders were similar to what became known as Dmowski's Line.

When Poland's constitution was being written in the early 1920s, Dmowski's party wanted a weak president and a strong parliament. Dmowski feared Piłsudski would become president and wanted to limit his power. The 1921 constitution indeed created a government with a weak executive branch. When Gabriel Narutowicz, a friend of Piłsudski, was elected president, Dmowski's party criticized him. A supporter of Dmowski's party later assassinated Narutowicz.

Dmowski was Minister of Foreign Affairs from October to December 1923. In 1926, after Piłsudski's May coup, Dmowski founded the Camp of Great Poland. He became more of a thinker than a leader as younger politicians emerged. In 1928, he founded the National Party. He continued to publish articles and books. By 1930, his health declined, and he mostly retired from politics.

Views on Nationalism

From his student days, Dmowski opposed socialism and wanted a strong, independent Polish state. He became an important European nationalist thinker. Dmowski believed in logic and reason over emotion. He thought Poles should focus on becoming businessmen and scientists instead of romanticizing the past.

In his 1902 book, Myśli nowoczesnego Polaka, Dmowski criticized Polish Romantic nationalism. He argued that Poland was a physical entity that needed to be built through practical actions, not through revolts that were likely to fail. He believed Poles needed "healthy national egoism."

Later, in 1927, he changed his view on Christianity. He began to see Catholicism as a key part of Polish identity. He wrote that "Catholicism is not a supplement to Polishness; it is somehow rooted in its very existence." Dmowski believed that all minorities weakened the nation and should either become Polish or leave.

Dmowski disliked Piłsudski and his ideas. Dmowski came from a less wealthy urban background and did not like Poland's old social structure. He wanted Poland to be modern. He disliked the old Commonwealth's multi-ethnic structure and religious tolerance. He saw ethnic minorities (Jews, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians) as a threat to Poland's culture and unity. He believed citizens should only be loyal to the Polish nation.

Dmowski admired Italian Fascism and helped organize the Camp of Great Poland, which was known for its anti-Jewish ideas. However, he tried to make sure his movement did not just copy Italian or German models.

Views on Minorities

Dmowski often expressed his belief in an "international Jewish conspiracy" against Poland. He claimed that Zionism was a cover for Jewish ambition to rule the world. He believed that the 3 million Polish Jews were too many to become part of Polish Catholic culture.

Dmowski suggested that all Jewish people should leave Poland to solve what he called Poland's "Jewish problem." He supported increasingly strict measures against the Jewish minority. He did not suggest violence, but instead promoted boycotts of Jewish businesses and their separation in cultural areas, such as limiting their access to universities.

He made anti-Semitism a main part of his party's nationalist ideas. In his 1938 essay Hitleryzm a Źydzi, Dmowski wrote that Jewish people influenced leaders like Wilson and Lloyd George to act against Poland's interests. He also believed that Germany was becoming more of a "Jewish state" than a German one.

Dmowski believed that not enough Polish-speaking Catholics were middle-class, while too many ethnic Germans and Jews were. He wanted to take wealth from Jews and ethnic Germans and give it to Polish Catholics. His party often organized "Buy Polish" campaigns against German and Jewish shops. He linked Jews with Germans as Poland's main enemies. He believed the Jewish community was not interested in Polish independence and might side with Poland's enemies.

Dmowski also strongly opposed freemasonry and feminism.

Death and Legacy

Dmowski's health weakened, and he moved to the village of Drozdowo. He died on January 2, 1939, at the age of 74.

He was buried at the Bródno Cemetery in Warsaw. His funeral was attended by at least 100,000 people. The government at the time did not send any official representatives.

Dmowski is considered one of the most important conservative politicians in modern Polish history. His legacy is debated, and he remains a very polarizing figure. He is called "the father of Polish nationalism" and an "icon of the contemporary Polish political right." As a signer of the Treaty of Versailles, he played a crucial role in Poland regaining independence after World War I.

However, he is also criticized for being the founder of modern Polish antisemitism and for his negative views on women's rights. Many academic articles and books have been written about Dmowski.

After the fall of communism in 1989, Dmowski's legacy became more widely recognized. A bridge in Wrocław was named after him in 1992. In November 2006, a statue of Roman Dmowski was unveiled in Warsaw. This led to protests from groups who see Dmowski as a fascist and an opponent of progressive politics.

On January 8, 1999, the Polish Sejm (parliament) honored him for his work for Polish independence and national awareness. The document also recognized him for creating a Polish school of political realism and for shaping Poland's borders. It also noted his emphasis on the strong link between Catholicism and Polishness for the nation's survival.

Dmowski received several state awards, including the Grand Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (1923). He also received honorary degrees from Cambridge University (1916) and the University of Poznań (1923). On November 11, 2018, he was given the Order of the White Eagle after his death.

Selected Writings

- Myśli nowoczesnego Polaka (Thoughts of a Modern Pole), 1902.

- Niemcy, Rosja a sprawa polska (Germany, Russia and the Polish Cause), 1908.

- Polityka polska i odbudowanie państwa (Polish Politics and the Rebuilding of the State), 1925.

- Kościół, naród i państwo (The Church, Nation and State), 1927.

See also

In Spanish: Roman Dmowski para niños

In Spanish: Roman Dmowski para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |