Émilie du Châtelet facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Émilie du Châtelet

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Maurice Quentin de La Tour

|

|

| Born | 17 December 1706 |

| Died | 10 September 1749 (aged 42) Lunéville, Kingdom of France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Translation of Newton's Principia into French, natural philosophy which combines Newtonian physics with Leibnizian metaphysics, and advocacy of Newtonian physics |

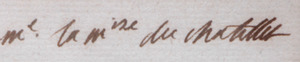

| Spouse(s) |

Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet-Lomont

(m. 1725) |

| Partner(s) | Voltaire (1733–1749) |

| Children |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural philosophy Mathematics Physics |

| Influences | Isaac Newton, Gottfried Leibniz, Willem 's Gravesande |

| Signature | |

|

|

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet (born December 17, 1706 – died September 10, 1749) was a brilliant French scientist and mathematician. She is best known for translating and explaining Isaac Newton's famous 1687 book, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. This book contains the basic laws of physics. Her translation was published after her death in 1756 and is still considered the best French version today.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Émilie du Châtelet was born in Paris, France, on December 17, 1706. She was the only girl among six children. Her father, Louis Nicolas le Tonnelier de Breteuil, was an important secretary to King Louis XIV. He often hosted famous writers and scientists at his home.

Émilie's father made sure she had a great education. When she was young, she learned physical activities like fencing and horseback riding. As she grew older, tutors came to her home to teach her. By age twelve, she could speak Latin, Italian, Greek, and German fluently. She later translated Greek and Latin plays and philosophy into French. She also studied mathematics, literature, and science.

One of her father's friends was Fontenelle, a leader of the French Académie des Sciences. When Émilie was 10, her father arranged for Fontenelle to visit and talk to her about astronomy. Émilie also loved to dance, play the harpsichord, sing opera, and act. As a teenager, she even used her math skills to win money gambling so she could buy books!

Her Marriage and Family

On June 12, 1725, Émilie married the Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet-Lomont. She was eighteen and he was thirty-four. This marriage was arranged, which was common for noble families. As a wedding gift, her husband became governor of Semur-en-Auxois in Burgundy. The couple moved there in September 1725.

Émilie and the Marquis had three children: Françoise-Gabrielle-Pauline (born 1726), Louis Marie Florent (born 1727), and Victor-Esprit (born 1733). Sadly, Victor-Esprit died as a baby. Émilie also had another daughter, Stanislas-Adélaïde, in 1749, who died as a toddler.

Returning to Her Studies

After having her children, Émilie decided to focus more on her studies. In 1733, at age 26, she began studying mathematics again. First, she was taught algebra and calculus by Moreau de Maupertuis, a member of the Academy of Sciences. By 1735, she was learning from Alexis Clairaut, a brilliant mathematician. Émilie always sought out the best teachers in France.

Once, she tried to join a discussion at Café Gradot, a place where men often met to talk about ideas. She was politely asked to leave because she was a woman. Not giving up, she had men's clothing made for herself and returned to join the conversation!

Working with Voltaire

Émilie du Châtelet might have met the famous writer Voltaire when she was a child. Their friendship grew stronger in May 1733. Émilie invited Voltaire to live at her country home in Cirey, France. They became close companions. There, she studied physics and mathematics, writing scientific papers and translations.

Voltaire and Émilie respected each other's work greatly. Voltaire even dedicated his 1738 book, Elements of the Philosophy of Newton, to her. He praised her studies and contributions in the book's introduction. Émilie also wrote a positive review of his book in a science journal.

They shared a love for science and worked together. They even set up a laboratory in Émilie's home. In 1738, they both entered a contest held by the Paris Academy about the nature of fire. Émilie disagreed with Voltaire's ideas, so they each submitted their own essays. Neither of them won, but both essays received special mention and were published. This made Émilie the first woman to have a scientific paper published by the Academy.

Later Life and Passing

Émilie du Châtelet passed away on September 10, 1749, at the Château de Lunéville. She was 42 years old.

Important Scientific Work

Understanding Warmth and Brightness

In 1737, Émilie du Châtelet published a paper called Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu (Dissertation on the Nature and Spread of Fire). In this paper, she explored the science of fire. She even suggested that there might be colors in other suns that we don't see in the sunlight on Earth.

Institutions de Physique

Her book Institutions de Physique (Lessons in Physics) came out in 1740. This book helped her become a member of the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna in 1746. In Institutions de Physique, Émilie discussed and combined ideas from many important scientists of her time, including Newton, Descartes, and Leibniz.

Her Lasting Impact

Émilie du Châtelet made a huge scientific contribution by translating Newton's important work into French. Her translation was accurate and included her own new ideas about how energy is conserved. This made Newton's complex ideas easier for more people to understand.

To honor her, a minor planet and a crater on Venus are named after her. She is also the subject of several plays and an opera. In France, the Institut Émilie du Châtelet was started in 2006 to support research about women and gender. Since 2016, the French Society of Physics has given out the Émilie Du Châtelet Prize for excellence in Physics. Duke University also gives an annual Du Châtelet Prize for new work in the philosophy of physics.

Her Writings

- Dissertation sur la nature et la propagation du feu (1739, 1744)

- Institutions de physique (1740, 1742)

- Principes mathématiques de la philosophie naturelle par feue Madame la Marquise du Châtelet (1756, 1759)

- Examen de la Genèse

- Examen des Livres du Nouveau Testament

- Discours sur le bonheur

See also

- In Spanish: Émilie du Châtelet para niños

Images for kids