The Huron Feast of the Dead facts for kids

The Huron Feast of the Dead was a special custom of the Wyandot people, who lived in what is now central Ontario, Canada. It was a time when they would carefully dig up their relatives' remains from their first graves. Then, they would rebury them together in one large, shared grave. This custom was very important for their spirits and culture. It was a time for both sadness and celebration.

When villages moved to new places, other Wyandot people would travel to join them. They would help arrange these large reburials. People would take the remains out of their first graves and clean them. This prepared the remains for reburial in the new spot. Over hundreds of years, these customs changed as people moved and their numbers grew. They always followed their traditional beliefs about the afterlife. When Europeans arrived, new things were added to the process. The Huron started exchanging gifts as a key part of these festivals. Some Wyandot people did not like these new practices. A French missionary named Jean de Brébeuf saw one of these ceremonies in 1636. It happened at the Wyandot capital called Ossossané, which is now in Simcoe County, Ontario. Later, in the 1900s, archaeologists dug up sites. Their findings confirmed many details about these traditions.

Contents

Early Customs Before European Contact

In the 1100s and 1200s, the Wyandot population grew quickly. Their villages and burial sites, called ossuaries, were small. Each village would rebury its dead separately when they moved. No ossuary from this early time held more than 30 people. The people left simple offerings in the graves. Even then, burials were shared by the community. This shared burial tradition continued even as other parts of Wyandot culture changed.

By the 1500s, the Wyandot population growth became steady. Before Europeans arrived, their burial customs began to look more like the Feasts of the Dead we know today. As the population grew, it became normal to wait several years between the first and second burials. This made the ossuaries much larger. They could hold hundreds of people.

Huron communities moved their villages every 10 to 15 years. They believed they needed to protect their dead when they moved. So, they started reburying them every time a large village relocated. These ceremonies happened at the end of winter. This was before the Huron started their spring farming and hunting. The idea of winter ending and spring beginning fit their beliefs about separating the living and the dead.

When the Wyandot moved to Wendake (near Georgian Bay in modern-day Simcoe and Grey counties in Ontario), these burial rituals became a symbol of unity. They showed the friendship between Wyandot groups. Many villages would gather for combined ceremonies. They would also exchange gifts. The gift exchange and the idea of a shared burial ground became key parts of the Feasts of the Dead.

Gabriel Sagard, a French missionary, wrote in the 1620s about why these rituals were important:

"By means of these ceremonies and gatherings they contract new unions and friendships amongst themselves, saying that, just as the bones of their deceased relatives and friends are gathered together and united in one place, so also they themselves ought during their lives to live all together in the same unity and harmony, like good kinsmen and friends."

These ceremonies helped build a strong sense of community among the people. They continued to be an important practice through the 1600s.

How Europeans Changed Burial Customs

Contact with Europeans brought new goods that were very useful. Getting these goods changed Wyandot society. It also changed their burial customs. Before Europeans, grave offerings were small. But after contact, the number and quality of goods offered to the dead became a sign of respect. Many important gifts were expected. They showed how generous and wealthy the giver was. They also were thought to ensure the good feelings of the souls of the dead.

This increase in offerings wasn't just because of European goods. Old records and archaeological digs show that many Indigenous items were also offered. The fur trade helped more goods move between Native groups. New tools also made crafting easier. People used their new wealth to show their devotion to these sacred customs.

The Feast of the Dead had become a way to strengthen alliances. After European contact, this became even more important. It was common to invite friends and family from other tribes. This helped promote Huron unity. All communities were told when a feast would happen. The dead were brought from far away so friends and relatives could be buried together.

Members of other Native groups were often invited to confirm strong bonds. But combined burials among different tribes were rare. During this time, the Feasts of the Dead were most impressive. Many gifts were exchanged to strengthen ties. The presence of visitors encouraged the Huron to impress them. These changes in customs both encouraged and needed the fur trade. Renewing alliances was a key part of the Feasts. In 1636, French missionaries were invited to a ceremony. This was to form an alliance and impress the Europeans. It also helped confirm the ties that kept the fur trade going.

The 1636 Feast at Ossossané

Jean de Brébeuf, a Jesuit missionary, was invited to a large Feast of the Dead in the spring of 1636. It took place outside the village of Ossossané, the capital of Wendake. His personal account gives us a unique look into Huron burial customs at that time. It is the most often used source on the topic. The Huron people scattered in 1650. This happened after diseases and conflicts with the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. Their cultural traditions changed after this big event. Brébeuf's account is a special view of a major feast. It happened when Huron burial customs were at their peak, just before their rapid decline.

The Feast of the Dead lasted for ten days. For the first eight days, people gathered and prepared the bodies for reburial. Relatives took out the remains and wrapped them in beaver robes. Any remaining flesh and skin were removed from the bodies. The bones were cleaned one by one. Then, they were wrapped again in another set of beaver furs. Women usually did this job. Showing any disgust was traditionally not allowed.

Wrapped in fur bundles, the bones were taken back to the relatives' homes. A feast was held there to remember the dead. Gifts and offerings were placed next to these bundles. Visitors were welcomed and treated very well. This was a time to feast and gather food and offerings for the main burial event.

The village leader announced when all families should transport the bodies. The journey to the new site was often long, possibly several days. It was a time for public mourning. People would make sharp cries. When the chief decided everyone was ready, all would gather around the burial pit for the main ceremony.

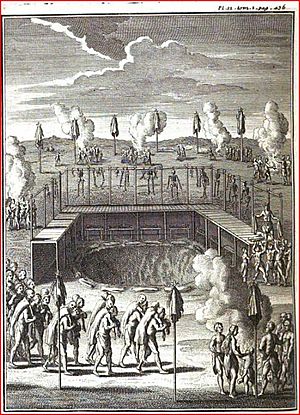

Brébeuf described the scene:

"There was in the middle of it a great pit, about ten feet deep and five fathoms in diameter. (...) Above rose many poles, trimmed and well arranged, with cross poles to attach the bundles of souls. (...)They laid on the ground their parcels (...) They unfolded also their bundles of robes and all the presents they had brought, and placed them upon poles (...) in order to give foreigners time to view the wealth and magnificence of the country."

He noted there were 15 to 20 baptized Huron among the dead. Rings with Christian symbols were later found at the site. That evening, the bodies were lowered into the pit with three kettles. These kettles were meant to help the souls reach the afterlife. If a bundle fell, everything else was thrown in too. This included bundles, gifts, corn, wooden stakes, and sand. As the pit was filled and covered, the crowds screamed and sang. Brébeuf said the scene was very emotional and lively. It showed how the Huron viewed life and death.

The next and final morning was for gift-giving among the living. It was a time for celebration. Those who had made the journey were thanked. Ties between people were made strong again.

The End of the Feasts

Many Wyandot people died from European diseases and warfare due to the fur trade. This caused the Feasts of the Dead to happen more often and become larger. This continued until the Wyandot people scattered in the mid-1600s. The last reported Feast of the Dead happened in 1695. It was held by both the Wyandot and Ottawa nations.

Archaeological Discoveries

Modern archaeology has found important information about Huron burial customs. It has revealed details about burial sites from before European contact or sites that were not written about. Archaeological evidence has also helped confirm what Brébeuf wrote about the 1636 feast.

Archaeological finds from burial sites began in the early 1800s. Often, these finds were accidental. As farmers moved into the area north of Lake Ontario, they accidentally plowed up areas that had been Huron ossuaries. The bones and grave goods had been untouched since they were buried. First, amateurs, and later, professional archaeologists documented the finds and dug up the sites. The information gathered has answered many questions.

Finds from before European contact have helped explain burial practices. They show how customs changed over three centuries.

| Find | Date | Number of Individuals | Durable Material Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Moatfield Ossuary | 1300 | 87 | 1 effigy pipe |

| The Uxbridge Ossuary | 1500 | 500 | Several Shell Beads |

Comparing these with more recent finds confirmed how burial customs continued to change.

Ossossané Excavation

Between 1947 and 1948, archaeologists from the Royal Ontario Museum uncovered the Ossossané burial site. This was the site Brébeuf had described. Kenneth E. Kidd led the excavation. It was praised for using modern and effective scientific methods. These methods added to and confirmed what was known about Huron Feasts of the Dead. The 3-Inch method helped preserve the layers of the site. It showed the order of individuals in graves and what burial goods were placed with them. The rich nature of the grave offerings was confirmed. Other details from Brébeuf’s account were also found to be accurate. The Jesuit's estimates about the size of the pit, the scaffolding, and its contents were quite correct. Comparisons with older sites showed how these traditions had changed. It also showed a big drop in the average age of the dead, from 30 to 21. This is believed to be evidence of disease epidemics.

| Find | Date | Number of Individuals | Durable Material Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ossossané | 1636 | at least 681 | 998 beads, 6 copper rings (1 Jesuit ring), two Amerindian pipes, 1 key |

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |