Battle of Falkirk Muir facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Falkirk Muir |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Jacobite rising of 1745 | |||||||

Monument erected to commemorate the battle |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8,000 | 7,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 130 killed and wounded | 370 killed and wounded | ||||||

| Official name | Battle of Falkirk II | ||||||

| Designated | 21 March 2011 | ||||||

| Reference no. | BTL9 | ||||||

The Battle of Falkirk Muir (also called the Battle of Falkirk) happened on 17 January 1746. It was part of the Jacobite rising of 1745, a fight to put Prince Charles Edward Stuart (also known as Bonnie Prince Charlie) back on the British throne.

Even though the Jacobites won this battle, it didn't change the overall outcome of the war much.

In early January 1746, the Jacobite army was trying to capture Stirling Castle. On January 13, British government troops, led by Henry Hawley, marched from Edinburgh to help the castle. They reached Falkirk on January 15. The Jacobites attacked them late on January 17.

The battle took place in bad light and heavy snow. One part of Hawley's army was defeated, but the other part held strong. Because of the confusion, the Jacobites didn't follow up their attack. This allowed the government troops to escape and gather again in Edinburgh. The Jacobites later left Stirling and went to Inverness. The rebellion ended a few months later at the Battle of Culloden in April.

Today, the battlefield is recognized and protected by Historic Scotland.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Jacobites had marched into England but then returned to Scotland. This journey was a big success for them and brought new fighters to their side. In late 1745, John Drummond arrived from France with weapons, money, and trained soldiers. By early January, the Jacobite army was at its strongest, with about 8,000 to 9,000 soldiers.

After a win at Inverurie in December, the Jacobites controlled northeast Scotland. They wanted to control the central parts too. Their main goal was Stirling Castle. This castle was very strong and important because it controlled the path between the Highlands and the Lowlands.

The Jacobite army split into two groups. The main group left Glasgow on January 4 to meet Drummond's troops at Stirling. Lord George Murray led one group through Falkirk towards Stirling. The other group went through Kilsyth to Bannockburn. Prince Charles set up his headquarters at Bannockburn House.

The town of Stirling quickly gave up, but the castle was much harder to take. It had strong defenses and 600 to 700 soldiers led by William Blakeney, a skilled soldier. The Jacobites started trying to capture the castle on January 8, but it was slow going.

On January 13, Henry Hawley, the British commander in Scotland, ordered his deputy, Major General John Huske, to march with 4,000 men towards Stirling. Hawley followed with another 3,000 soldiers. They reached Falkirk on January 15 and set up camp. Murray pulled his troops back to Plean Muir, where Charles and O'Sullivan joined him with more soldiers from the castle siege.

The Battle Begins

Both sides had problems with their leaders. Hawley had fought in battles before and thought his cavalry could easily defeat the Highlanders. But he didn't realize how good the Highlanders were at fighting. The Jacobite leaders also had disagreements. Prince Charles and his foreign advisors often argued with the Scottish commanders, especially Murray.

Hawley didn't attack on January 16. So, Murray, Charles, and O'Sullivan decided to attack on the morning of January 17. Some of Drummond's soldiers marched towards Stirling to trick the British scouts. Meanwhile, Murray's Highlanders moved to the high ground south of the British camp. Hawley thought the Jacobites wouldn't dare attack him and was a mile away at Callendar House.

Around noon, the British soldiers were told to get ready for battle, but then stood down. It wasn't until 2:30 PM that Hawley realized the danger. The weather suddenly turned bad, with heavy rain and snow. A strong wind blew right into the faces of Hawley's troops.

The British army moved south towards the Falkirk ridge. Their cavalry, called dragoons, led the way. Their horses churned the ground into mud, making it hard for the foot soldiers to follow. The cannons got stuck in the mud and couldn't be used in the battle. The rain also made the soldiers' gunpowder wet, so many of their guns didn't fire.

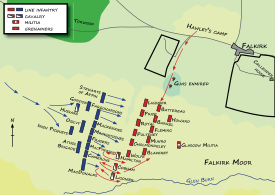

The dragoons stopped at the top of the ridge, with a swampy area to their left. The foot soldiers lined up to their right. The front line had dragoons and six groups of experienced foot soldiers. Behind them were five more groups of foot soldiers, and then another regiment and 1,000 local militia. The inexperienced Glasgow militia were kept further back.

Facing them was the Jacobite army. The Highland regiments were in the front line. Behind them were Lowland units, then a small number of cavalry and 150 French-Irish soldiers. Murray rode with the MacDonalds on the far right, facing the dragoons. He made sure they stayed in line and told them not to fire until he gave the order.

Murray thought their position was perfect. But the Jacobite left side was missing its commander, Drummond, when the battle started. He arrived later, but this meant that part of the army didn't have a senior leader at the beginning.

The Fight and Retreat

Just after 4:00 PM, the dragoons attacked the MacDonalds. The MacDonalds waited until the dragoons were very close, then fired a single shot. Just like at an earlier battle called Prestonpans, the dragoons quickly ran away in confusion. They were blocked by the swamp on their left. Two of the dragoon regiments rode over their own foot soldiers who were forming up behind them. In just a few minutes, the entire left side of the British army was gone. The Jacobites seemed to be on their way to a huge victory.

However, the MacDonalds and the rest of the Jacobite front line charged down the hill and started looting the British camp. Because of the sloped ground and poor visibility, Murray couldn't see what was happening. Three groups of British soldiers, led by Huske and Cholmondeley, held their ground. They were protected by a deep ditch in front of them and fought off attacks from the Jacobite left. These Jacobite soldiers then ran away too. Many didn't stop until they reached Stirling, thinking they had lost the battle.

The darkness, the ongoing storm, and the general confusion on both sides brought the battle to an end. Hawley first pulled back to Falkirk, but most of his army was spread out on the road to Linlithgow. They eventually returned to Edinburgh to regroup.

The British artillery commander left his cannons and used the horses to escape. When Huske's men retreated, they managed to drag some cannons with them, but most were left behind. The commander later took his own life. Ligonier, who was sick but came to command, died shortly after the battle. The severe weather was so bad that Cholmondeley suffered from extreme cold.

Like many battles back then, most deaths happened during the chase after the main fight. This was also true at Culloden later, but with the roles reversed. It's thought that the Jacobites lost about 50 killed and 80 wounded. The British lost around 70 killed and 200-300 wounded or missing. Twenty of the dead British were officers, including Sir Robert Munro and his younger brother Duncan. They were buried in St Modan's, Falkirk.

What Happened Next

Even though the Jacobites won at Falkirk, it's often called a "hollow" victory. This is because poor leadership and communication stopped them from winning a complete victory. One reason for the confusion was that Charles and O'Sullivan, from their position on the left, first thought they had lost. Murray publicly blamed Drummond for being late and not helping his success on the right. Drummond blamed Murray for the MacDonald regiments not pushing their attack. Murray also accused O'Sullivan of being a coward. Amid these arguments, Charles returned to Bannockburn and became ill.

On January 29, Cumberland arrived in Edinburgh and took command of the British forces. Some British soldiers were later punished for leaving their posts. Hawley's poor leadership helped the Jacobites, but he was not put on trial like some other commanders.

The Jacobite leaders didn't understand that while Highland clans could quickly gather many men, they usually expected battles to be short and not in winter. After a successful battle like Prestonpans, many Highlanders went home to protect their loot. The clan chiefs couldn't stop them from leaving after Falkirk either. When Cumberland started his advance again on January 30, Charles asked Murray for a battle plan. But Murray said the army was not ready to fight. This destroyed the last bit of trust between them. On February 1, 1746, the Jacobites gave up trying to capture Stirling and retreated to Inverness.

Remembering the Battle

There are plans to build a visitor center at South Bantaskine Estate to remember the Battle of Falkirk Muir.

Images for kids