Planned French invasion of Britain (1759) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids French invasion of Great Britain |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Seven Years' War and the Jacobite risings | |||||||

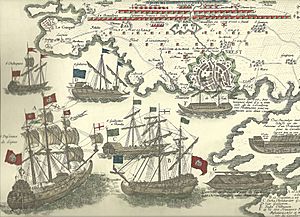

Battle of Quiberon Bay which ended the invasion plans |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Ligonier Edward Hawke |

Duc d'Aiguillon Charles de Soubise Comte de Conflans |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 regular troops, 30,000+ militia | 100,000 soldiers | ||||||

In 1759, during the Seven Years' War, France planned a huge invasion of Great Britain. The goal was to land 100,000 French soldiers in Britain. This would force Britain to stop fighting in the war. However, this invasion never happened. It was stopped by several things, including important naval defeats for France at the Battle of Lagos and the Battle of Quiberon Bay. This was one of many times France tried and failed to invade Britain in the 1700s.

Contents

Why the Invasion Was Planned

The Seven Years' War was a big global conflict that started in 1756. Before this, the War of the Austrian Succession ended in 1748. But no one was really happy with the peace treaty. Austria wanted to get back a region called Silesia from Prussia. So, Austria decided to become friends with France, who used to be their enemy. France agreed because they wanted to focus on fighting Great Britain.

Because of this, Prussia, a new strong power, teamed up with Great Britain. By 1755, Britain and France were already fighting at sea and in North America. For example, British soldiers invaded French North America. The British navy also captured many French fishing boats, hurting France's economy and reducing their number of experienced sailors. When Prussia invaded Saxony in 1756, it officially started the Seven Years' War. France supported Austria and Russia in Europe. They also focused on fighting Britain at sea and in their colonies.

By early 1759, neither side was clearly winning the war. Both France and Great Britain were running out of money. France was in a very bad financial situation. Their navy was also struggling and not well organized. Meanwhile, Britain's war effort had been difficult at first. But from 1757, William Pitt took charge. He created a strong plan to push France out of North America and hurt their trade. This plan started to work by early 1759.

Planning the Invasion

How the Idea Started

The invasion plan was created by the Duc de Choiseul. He became France's foreign minister in December 1758. He was basically the Prime Minister at the time. Choiseul wanted to do something big to knock Britain out of the war. France was upset because Britain had easily captured Louisbourg and raided the French coast in 1758. Britain was also helping its ally, Prussia, with money and soldiers. Choiseul's job was to change this situation.

Choiseul thought about invading Britain. He knew Britain's main strength was its navy. But he believed that if a large French army could cross the Channel without being stopped, they could easily beat Britain's small army on land. Choiseul first thought they didn't need French warships to protect the invasion. He believed that trying to get warships out of the blockaded port of Brest would cause delays and problems. He thought a mixed force of warships and transport ships would fail, like the Spanish Armada had. A previous French attempt in 1744 had also failed.

His plan was quite simple: a huge fleet of flat-bottomed transport boats would carry 100,000 soldiers across the Channel. They would land on the coast of southern England. Speed was very important for this plan. The French would wait for good wind and cross the Channel quickly. Once they landed, they believed they could easily defeat Britain's small home army and end the war. Choiseul convinced others in the French government to approve the invasion. It became the main part of France's plan for 1759.

Jacobite Help and Other Allies

As part of the plan, the French thought about starting a Jacobite rebellion. They had done this in 1745. This would involve sending Charles Edward Stuart, the Jacobite leader, with or before the invasion forces. A secret meeting happened with Charles Stuart in Paris in February 1759, but it did not go well. Choiseul decided that the Jacobites would not be much help. So, he removed them from the main plan.

From then on, any French landing would be done only by French troops. However, Choiseul did think about sending Charles to Ireland. There, he could be declared King of Ireland and lead a rebellion. In the end, the French decided to try and get Jacobite supporters without directly involving Charles. They thought he might cause problems.

France also asked Denmark and Russia for soldiers and supplies. But both countries refused to join. Sweden first agreed to send an invasion force to Scotland, but later changed its mind. The Dutch Republic, usually an ally of Britain but neutral at the time, was worried. They asked for promises that France was not planning to put Charles Stuart on the British throne. They believed this would threaten their own safety. The French ambassador told them they were not.

French Preparations

Throughout 1759, France continued its preparations. Hundreds of flat-bottomed transport boats were built in many ports like Le Havre, Brest, and St Malo. About 30 million French money units were spent on building these boats. Some small, well-armed escort ships were also built. By mid-summer, over 325 transport ships were almost ready. About 48,000 soldiers were prepared for the invasion. Drills showed that French troops could get on and off the ships in just seven minutes.

The plan changed a few times during the year, but the main idea stayed the same. Even though some in the French government disagreed, Choiseul insisted on crossing the Channel without the main French fleet. The French decided to launch the main invasion force from Le Havre. This was a large harbor far from the British fleet blockading Brest. A smaller force would leave from Dunkirk to distract the British.

In June, French planners decided that a separate, smaller force would go to Scotland. This force would try to get Jacobite support and attack British resistance from two sides. The Duc d'Aiguillon was chosen to lead this force. They hoped about 20,000 Scottish Jacobites, mostly Highland clansmen, would join him after landing near the Clyde. Prince Soubise was given command of the larger southern invasion. His force was supposed to wait for good winds. Then, they would quickly cross the Channel from Le Havre and land in Portsmouth.

Raid on Le Havre

In early July, a surprise British raid on Le Havre caused a lot of damage. Many transport ships were destroyed. However, this success made the British commanders too confident. They thought the damage was worse than it actually was. The French wanted to use this to their advantage, but they had to reduce their initial plans. A War Council in Paris decided to send the expedition to Scotland first. If it succeeded, they would send more forces to Portsmouth and Maldon, Essex. The exact details were kept flexible to allow for changes.

Delays in getting the invasion force ready pushed back the launch date. The sea also became rougher and more dangerous. Some French leaders were worried about sending the fleet out in bad weather. But the need for a big victory to boost French morale and get a good peace deal was more important. In October, D'Aiguillon arrived at his command center near where his army had gathered. For five days after October 15, British ships blockading the French coast had to leave because of a storm. This left the French invasion forces free to sail. But the French commander, Conflans, decided not to leave the harbor. He believed his fleet was not ready. On October 20, the British returned and blockaded the French Atlantic ports again.

Battle of Lagos

In summer 1759, the French Toulon fleet, led by Admiral La Clue, managed to slip past the British blockade. They sailed through the Straits of Gibraltar. But they were caught and defeated by a British fleet at the Battle of Lagos in August. Their original plan was to go to the West Indies. But losing ships and men severely weakened the French fleet. This also made people question if the invasion of Britain was still possible.

Battle of Quiberon Bay

The invasion plan suffered a huge blow in November. The French Brest Squadron was heavily defeated at the Battle of Quiberon Bay. Conflans had sailed from Brest on November 15. He went about a hundred miles down the coast to Quiberon Bay. The invasion army was waiting there to get on his transport ships. Conflans' fleet got caught in a storm, which slowed them down. This allowed the chasing British fleet, led by Sir Edward Hawke, to catch up.

The two fleets met at the mouth of Quiberon Bay on November 21. Conflans first lined up his ships to fight. But then he changed his mind, and his ships raced to find shelter in the bay. Hawke chased them, taking a big risk in the middle of a violent storm. He captured or drove ashore five French ships. The rest managed to find shelter in the bay. But they were now trapped by the British fleet. Most of the French ships were abandoned, and their guns were removed. Only three of these ships ever sailed again. This was a terrible defeat for the French Channel fleet. The crushing loss at Quiberon Bay ended any real hope of a major invasion of the British Isles.

Landing in Ireland

A French privateer (a privately owned ship allowed to attack enemy ships), François Thurot, sailed from Dunkirk with five ships. His goal was to create a distraction for the main invasion. In 1760, he landed on the northern Irish coast and set up a base at Carrickfergus. If he hadn't argued with the commander of the land expedition, his force might have captured Belfast, which was not well defended. When he sailed for home, the British Royal Navy killed Thurot and destroyed his ships in the Irish Channel. By this time, the French had already given up on the main invasion. However, many French people felt encouraged by Thurot's trip. It showed that French forces could land in the British Isles.

Why the Invasion Was Called Off

With the Brest fleet destroyed at Quiberon Bay, they could no longer protect the French troops crossing the Channel. Some people started asking Choiseul to go back to the original plan of crossing without a fleet. They suggested postponing the invasion until early 1760.

1759 was a terrible year for France in the war. They suffered big defeats in Canada, the West Indies, Europe, and India. Choiseul was especially disappointed by how poorly the French navy performed. As news of these disasters came in, it became clear how stretched France's forces were. They needed the French soldiers planned for the invasion elsewhere, especially in Germany to fight Hanover. So, Choiseul sadly called off the invasion.

He still hoped it might be possible later. But the war continued to go badly for France over the next few years. This was especially true when Spain joined the war as a French ally in 1761. Choiseul started to plan a new invasion in 1762. But this was also stopped when a peace agreement was signed.

What Happened Next

The French completely gave up the invasion plan in 1763. That's when the Peace of Paris officially ended the fighting. Choiseul continued to believe that attacking Britain directly was the way to win future wars. He sent engineers and agents to study British defenses. During the Falklands Crisis of 1770, he suggested a similar attack. But the French King, Louis XV, dismissed him. Other French invasions were planned in 1779 during the American War of Independence. Napoleon also planned one in 1803–04. But none of these invasions ever happened, for many of the same reasons Choiseul's 1759 plan failed.

See also

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |