Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard facts for kids

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard is a famous poem by Thomas Gray. He finished it in 1750, and it was first published in 1751. The poem was partly inspired by Gray's thoughts after his friend, the poet Richard West, passed away in 1742.

The poem is called an elegy, which is a sad poem, usually about someone who has died. However, it doesn't follow the usual rules for this type of poem. Instead, it's like a deep thought about death and how people are remembered after they are gone. The poem suggests that being remembered can be both good and bad. The person telling the story finds comfort in thinking about the lives of the ordinary people buried in the churchyard.

This poem quickly became very popular. It was printed many times and translated into many languages. Critics praised it, even when Gray's other poems were not as well-liked. Many people still admire its language and its message, which applies to everyone.

Contents

How the Poem Came to Be

Thomas Gray experienced a lot of sadness and loss in his life. Many people he knew died. In 1749, several difficult things happened to him. On November 7, his aunt, Mary Antrobus, died, which made his family very sad. A few days later, his childhood friend Horace Walpole was almost attacked by robbers. Even though Walpole was okay, these events made it hard for Gray to focus on his studies.

These sad events made Gray think a lot about his own life and what happens after death. He wondered if he would be remembered if he died. In the spring of 1750, Gray started thinking about how people's reputations last. He remembered some lines of poetry he wrote in 1742 after his friend Richard West died. He used these old lines to help him write a new poem that would answer his questions about life and death.

Finishing and Publishing the Poem

On June 3, 1750, Gray moved to Stoke Poges, a village in England. He finished Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard there on June 12. He immediately sent the poem to his friend Horace Walpole. Gray didn't think the poem was very important. He just felt good that he had finally finished it. He was probably inspired by the churchyard at Stoke Poges, where he went to church and could visit his aunt's grave.

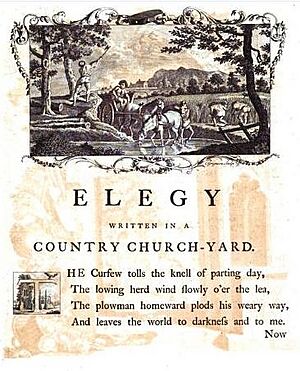

Walpole shared the poem with his friends in London, and it became very popular throughout 1750. By February 1751, Gray heard that a magazine publisher named William Owen was going to print his poem without his permission. Back then, copyright laws didn't stop this. So, with Walpole's help, Gray quickly got a publisher named Robert Dodsley to print the poem on February 15, 1751, a day before Owen's magazine.

Walpole wrote a short introduction for the poem. It said that the poem was found by chance and was already very popular. He hoped Gray would forgive him for sharing it with more people. The printed poem had woodblock illustrations and didn't say Gray's name, as he wished. Owen's magazine printed the poem too, but it had many mistakes. Gray thanked Walpole for helping to get a good version published first. The poem was so popular that it was reprinted many times.

What Kind of Poem Is It?

The Elegy is not a typical elegy, which usually mourns one specific person. Instead, it talks about the general sadness of being human. It doesn't have many common elegy features like special prayers or flowers. Its main focus isn't on loss, and the natural setting isn't just a pretty background.

The poem ends with an "Epitaph," which is like a message on a tombstone. This makes it a memorial poem. It shares themes with elegies, especially sadness. However, it's different from poems like John Milton's "Lycidas", which are very fancy. Gray's poem feels more natural.

English Countryside and Personal Feelings

The poem describes the English countryside, like other "picturesque" poems of the time. But it's special because it focuses on the death of a poet. Many parts of the poem are about Gray's own life. While writing it, he faced the deaths of others and thought about his own life ending. Even though the poem talks about life and death in a way that applies to everyone, it came from Gray's own feelings. It was almost like an epitaph for himself.

The poem also mourns others, like his friend West. However, Gray tried to avoid the scary descriptions often found in other "graveyard poems." He didn't want to make death seem horrible. Instead, the person telling the story tries not to get too emotional about death. They ask questions and talk about what isn't there. Still, people saw a connection between Gray's poem and Robert Blair's "The Grave." Because of this, Gray's Elegy was often printed with Blair's poem.

Poem's Style and Language

The Elegy is similar to the odes Gray also wrote. As the poem changed from its first version, it became more like the style of John Milton. The poem uses "English" ways of writing and language. The stanza form, which is four lines with an ABAB rhyme scheme, was common in English poetry since the 1500s. Gray used foreign words but mixed them with English words to make them feel "English." Many foreign words Gray used were already in works by Shakespeare or Milton, which helped keep the "English" feel. He also used many short, one-syllable words to give it a countryside English feel.

The Poem's Story

The poem starts in a churchyard. The speaker describes everything around him in great detail. He pays attention to both sounds and sights as he looks at the area and thinks about himself:

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea,

The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

Now fades the glimmering landscape on the sight,

And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds:

Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow’r

The moping owl does to the moon complain

Of such, as wand’ring near her secret bow’r,

Molest her ancient solitary reign. (lines 1–12)

As the poem goes on, the speaker focuses less on the countryside and more on his immediate surroundings. His descriptions change from what he sees and hears to his own thoughts. He starts to think about what is missing from the scene. He compares a simple, unknown country life with a life that is remembered. This thinking makes the speaker wonder about wasted potential and talents that are never used.

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear:

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

Some village Hampden, that, with dauntless breast,

The little tyrant of his fields withstood,

Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

Some Cromwell guiltless of his country’s blood.

Th’ applause of list’ning senates to command,

The threats of pain and ruin to despise,

To scatter plenty o’er a smiling land,

And read their history in a nation’s eyes,

Their lot forbade: nor circumscrib’d alone

Their growing virtues, but their crimes confined;

Forbade to wade thro’ slaughter to a throne,

And shut the gates of mercy on mankind,

The struggling pangs of conscious truth to hide,

To quench the blushes of ingenuous shame,

Or heap the shrine of luxury and pride

With incense kindled at the Muse’s flame. (lines 53-72)

The speaker thinks about how death makes everyone equal, hiding individuals. He starts to accept that he, too, will die. As the poem ends, the speaker talks directly about death and how people want to be remembered. Then, the poem shifts. The first speaker is replaced by a second speaker, who describes the death of the first:

For thee, who, mindful of th’ unhonour’d dead,

Dost in these lines their artless tale relate;

If chance, by lonely contemplation led,

Some kindred spirit shall inquire thy fate,—

Haply some hoary-headed swain may say,

"Oft have we seen him at the peep of dawn

Brushing with hasty steps the dews away,

To meet the sun upon the upland lawn. (lines 93-100)]

The poem finishes by describing the grave of the poet the speaker was thinking about. It also tells about the end of the poet's life:

There at the foot of yonder nodding beech,

That wreathes its old fantastic roots so high,

His listless length at noontide would he stretch,

And pore upon the brook that babbles by.

Hard by yon wood, now smiling as in scorn,

Mutt’ring his wayward fancies he would rove;

Now drooping, woeful-wan, like one forlorn,

Or craz’d with care, or cross’d in hopeless love.

One morn I miss’d him on the custom’d hill,

Along the heath, and near his fav’rite tree;

Another came; nor yet beside the rill,

Nor up the lawn, nor at the wood was he;

The next, with dirges due in sad array

Slow through the church-way path we saw him borne:—

Approach and read (for thou can’st read) the lay

Grav’d on the stone beneath yon aged thorn. (lines 101-116)

After the poem, there is an epitaph. This epitaph tells us that the poet buried in the grave was unknown and not famous. Life's circumstances kept him from becoming greater. He was different from others because he couldn't join in their everyday lives:

Here rests his head upon the lap of earth

A youth, to fortune and to fame unknown:

Fair science frown’d not on his humble birth,

And melancholy mark’d him for her own.

Large was his bounty, and his soul sincere,

Heaven did a recompense as largely send:

He gave to mis’ry (all he had) a tear,

He gain’d from heav’n (’twas all he wish’d) a friend.

No farther seek his merits to disclose,

Or draw his frailties from their dread abode,

(There they alike in trembling hope repose,)

The bosom of his Father and his God.

Main Ideas in the Poem

The poem is like many older British poems that think about death and try to make it seem less scary. However, compared to other "graveyard poems," Gray's poem doesn't focus as much on common scary images. His descriptions of the moon, birds, and trees make it less frightening. He also mostly avoids using the word "grave," using softer words instead.

There's a different feeling between the two versions of the poem. The early version ends with the narrator joining the ordinary, unknown people. The final version ends by saying that it's natural for people to want to be remembered. The later ending also explores the narrator's own death.

The poem talks about how the narrator looks at his surroundings. Gray used ideas from John Locke, a philosopher, who believed that our senses are how we get ideas. The descriptions at the beginning of the poem are used by the narrator to think about life later on. The poem's discussion of death and being unknown uses Locke's ideas about how death is certain and final. The end of the poem connects to Locke's ideas about how we can only understand so much about the world. The poem takes these ideas and turns them into a discussion about being happy with what we know, even if it's limited.

Ordinary vs. Famous Lives

Scholar Lord David Cecil said that in the poem, "Death... makes human differences seem small. There isn't much difference between the great and the humble once they are in the grave." He also suggested that perhaps the unknown people in the graveyard could have been as famous as John Milton or John Hampden if their lives had been different.

However, death isn't completely fair. If circumstances stopped these people from becoming famous, they also saved them from doing terrible things. Yet, there's a special sadness in these unknown graves. The simple words on the plain tombstones remind us how much all people, even the most humble, want to be loved and remembered.

The poem ends with the narrator thinking about his own future, accepting his life and what he has done. Like many of Gray's poems, it has a narrator who thinks about his place in a changing world that feels mysterious and sad. While the comparison between being unknown and being famous is often seen as a universal message, Gray's choices also have political meanings. Both John Milton and John Hampden lived near Stoke Poges, where the poem is set, and this area was affected by the English Civil War.

Many experts believe the poem's message is too general to need a specific event for inspiration. But Gray's letters suggest that historical events did influence him. For example, Gray might have been interested in discussions about how the poor were treated. He probably supported the idea that poor people who worked hard should be helped, but he didn't want to change their social position. Instead of talking about economic unfairness, Gray tried to include different political views. The poem's main message is to celebrate "Englishness" and the peaceful English countryside.

How the Poem Influenced Others

The Elegy became very popular right away. By the mid-1900s, it was still one of the most well-known English poems, though its fame might have lessened a bit since then. It has influenced many things.

Other Poems and Writers

By choosing an "English" setting instead of a Classical one, Gray gave other poets a model for describing England and its countryside in the late 1700s. After Gray, many poems were written that showed how time affects a landscape. For example, John Scott of Amwell's Four Elegies, descriptive and moral (1757) described the changing seasons. Other poems, while not copying Gray's exact words, chose similar settings to show their connection to his work. A popular theme was thinking among old ruins.

People have noticed a connection between Gray's Elegy and Oliver Goldsmith's The Deserted Village. Goldsmith's poem was more openly political about the poor in the countryside. These two poems were often printed together. An old review from 1896 even said that "Gray's 'Elegy' and Goldsmith's 'The Deserted Village' shine forth as the two human poems in a century of artifice."

The Elegy continued to influence poets in the 1800s, especially the Romantic poets. They often tried to define their own beliefs by reacting to Gray's poem. For example, Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote his own poem about graves in 1815, which was similar to Gray's but concluded that death can be appealing and not scary.

In the Victorian era, Alfred, Lord Tennyson used many ideas from the Elegy in his long poem about death, In Memoriam. He created a serious, almost religious tone by using the idea of a "knell" (a bell ringing for a death) that "tolls" to mark the coming night. This is followed by the poet reading letters from his dead friend, just like Gray's narrator reads tombstones to connect with the dead. Robert Browning used a similar setting to the Elegy in his poem "Love Among the Ruins." He talked about wanting fame and how everything ends in death. But unlike Gray, Browning added a female character and argued that only love truly matters.

Thomas Hardy, who had memorized Gray's poem, took the title of his famous novel, Far from the Madding Crowd, from a line in the Elegy. Also, many poems in his Wessex Poems and Other Verses (1898) have a graveyard theme and share similar ideas with Gray's poem.

It's also possible that parts of T. S. Eliot's Four Quartets came from the Elegy. Eliot believed that Gray's language was too strict. But the Four Quartets cover many of the same ideas, and Eliot's village is like Gray's hamlet. There are many echoes of Gray's words in the Four Quartets. Both poems use the yew tree as an image and the word "twittering," which was unusual at the time.

Parodies and Other Versions

One expert said that "Gray's Elegy has probably inspired more adaptations than any other poem in the language." This means many writers have created their own versions or funny imitations of it. One of the earliest parodies was John Duncombe's "An evening contemplation in a college" (1753). This was often reprinted alongside translations of the Elegy into Latin and Italian.

Many of these new versions changed the setting of the poem. For example, Edward Jerningham wrote The Nunnery: an elegy in imitation of the Elegy in a Churchyard in 1762. Its success led him to write other poems about nuns that kept a similar theme and feeling to Gray's work. Gray's poem also provided a format for many poems about life in prison.

Funny or satirical versions of the poem appeared in newspapers and comic magazines for a century and a half. In 1884, about eighty of them were mentioned in a book called Parodies of the works of English and American authors. This shows how much the poem continued to influence people.

Translations into Other Languages

The latest list of translations of the Elegy includes over 260 versions in about forty languages. These include major European languages and some smaller ones like Welsh and Icelandic, as well as several Asian languages. Through these translations, the Romantic style of writing came to other literatures in Europe. In Asia, they offered a new way of writing that was different from traditional styles and helped bring in modern ideas.

Studying these translations, especially those made soon after the poem was written, shows some of the difficulties of the text. These include unclear word order and the fact that some languages can't easily show the subtle way Gray includes himself in the poem's first stanza: "And leaves the world to darkness and to me."

Gray himself talked about the challenges of translating his poem into Latin. He said that every language has its own way of speaking and its own customs that are hard to show in another language, especially one from a different time and place. He mentioned things like the curfew bell, the Gothic church, and the beetle flying in the evening, saying they might seem too ordinary for Latin poetry. However, translators found ways to include these details.

The Elegy in Other Arts

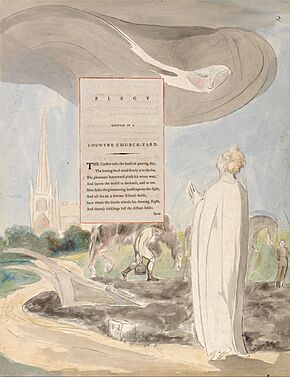

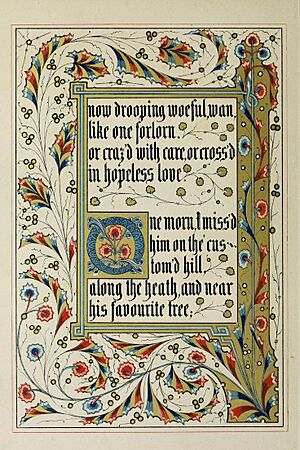

Many editions of the Elegy have included illustrations. The work of two famous artists is especially important. Between 1777 and 1778, William Blake was asked to create illustrated versions of Gray's poems as a gift. These were watercolors, and twelve of them were for the Elegy. Another special book was made in 1910 by Sidney Farnsworth, with handwritten text and beautiful decorations.

Another notable illustrated edition was created in 1846 by Owen Jones. Each of its 35 pages was uniquely designed with colorful borders. The cover was made of embossed leather to look like carved wood. Earlier, the librarian John Martin had gathered designs from John Constable and other major artists to illustrate the Elegy. These designs were then carved into wood for the first edition in 1834.

While not an illustration itself, Christopher Nevinson's painting Paths of Glory (1917), which protested the slaughter of World War I, takes its title from a line in the Elegy: "The paths of glory lead but to the grave." This title was also used for Stanley Kubrick's film Paths of Glory in 1957. This shows how certain lines from the poem continue to be used and remembered, even far from their original meaning.

Since the poem is long, there haven't been many full musical versions. Musicians in the 1780s often chose to set only parts of it to music. For example, W. Tindal set the "Epitaph" to music in 1785. Later, in 1883, Alfred Cellier set the entire work as a cantata, a piece of music for singers and instruments.

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |