Conrad Gessner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Conrad Gessner

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Tobias Stimmer, c. 1564

|

|

| Born | 26 March 1516 Zürich, Swiss Confederacy

|

| Died | 13 December 1565 (aged 49) Zürich, Swiss Confederacy

|

| Resting place | Grossmünster, Zürich |

| Education | Carolinum, Zürich |

| Alma mater | University of Basel, University of Montpellier |

| Known for | Bibliotheca universalis and Historia animalium |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany, zoology and bibliography |

| Influenced | Felix Plater |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Gesner |

Conrad Gessner (born March 26, 1516 – died December 13, 1565) was a famous Swiss doctor and scientist. He was a naturalist, meaning he studied nature. He also worked as a bibliographer, which means he cataloged books.

Conrad Gessner came from a poor family in Zürich, Switzerland. But his teachers quickly saw how smart he was. They helped him go to university. There, he studied old languages, religion, and medicine. He became the city's doctor in Zürich. This job allowed him to spend a lot of time collecting information, doing research, and writing.

Gessner created huge books about books (called Bibliotheca universalis) and animals (called Historia animalium). He was also working on a big book about plants. Sadly, he died from the plague when he was only 49. Many people call him the father of modern scientific bibliography, zoology, and botany. He was often the first person in Europe to describe new plants or animals, like the tulip in 1559. Many plants and animals are named after him today.

Contents

Conrad Gessner's Early Life and Studies

Conrad Gessner was born on March 26, 1516, in Zürich, Switzerland. His father, Ursus Gessner, was a furrier and not wealthy. Conrad's early life was difficult because his family was poor. However, his father saw his talents. He sent Conrad to live with a great-uncle. This great-uncle grew and collected plants for medicine. Living with him, young Conrad learned a lot about plants. This sparked his lifelong interest in nature.

Gessner first went to the Carolinum school in Zürich. Later, he joined the Fraumünster seminary. He studied classical languages there. At age 15, he even acted in a play! His teachers were so impressed by him. Some of them helped him get a scholarship. This allowed him to study theology in France when he was 17. He went to the University of Bourges and the University of Paris.

He had to leave Paris because of religious problems. He went to Strasbourg but couldn't find work. So, he returned to Zürich. After his father died, some of his teachers helped him. One teacher gave him free room and food for three years. Another helped him continue his education in Strasbourg. There, he learned even more about ancient languages, including Hebrew.

In 1535, more religious unrest sent him back to Zürich. At 19, he got married. Some thought this was not a good idea because his wife also came from a poor family. Even though some friends helped him, his first teaching job paid very little. But then, he got paid time off to study medicine. He went to the University of Basel in 1536.

Throughout his life, Gessner loved natural history. He collected many plant and animal samples. He also wrote to other scientists and scholars. His way of doing research was new for his time. He would:

- Observe things closely.

- Dissect (carefully cut open) specimens.

- Travel to different places.

- Describe everything accurately.

Before Gessner, most scholars just read old books for their research. Gessner's hands-on approach was a big change. He died from the plague on December 13, 1565.

Conrad Gessner's Amazing Work

Conrad Gessner was a true polymath. This means he was skilled in many different subjects. He was a doctor, a philosopher, and an encyclopaedist. He also worked as a bibliographer, a philologist (someone who studies languages), and a natural historian. He was also a talented illustrator.

In 1537, at age 21, he published a Latin-Greek dictionary. Because of this, his supporters helped him get a job. He became a professor of Greek at the new academy in Lausanne. This job gave him time to study science, especially botany. He also earned money to continue his medical studies.

After teaching in Lausanne for three years, Gessner went to medical school. He studied at the University of Montpellier. He earned his doctoral degree in 1541 from Basel. Then, he went back to Zürich to work as a doctor. He continued this work for the rest of his life. He also taught about Aristotle's physics at the Carolinum. This school later became the University of Zürich.

After 1554, he became the city's official doctor. Besides his duties, he traveled a bit. He also took yearly summer trips to the mountains to collect plants. He loved climbing mountains for exercise and to enjoy nature. In 1541, he wrote about the wonders of the mountains. He said he would climb at least one mountain every year. He did this not just for plants, but also for his health. In 1555, he wrote about his trip to the Gnepfstein mountain.

Gessner was the first to describe many species in Europe. These included animals like the brown rat, guinea pig, and turkey. He also described plants like the tulip. He first saw a tulip in April 1559. He called it Tulipa turcarum, which means "Turkish tulip." He was also the first to describe brown adipose tissue in 1551. In 1565, he was the first to write about the pencil. And in 1563, he was among the first Europeans to write about tobacco.

Gessner's Important Books

Gessner's first book was a Latin-Greek Dictionary in 1537. It was called the Lexicon Graeco-Latinum. Over his life, he wrote about 70 books on many different topics.

His next big project was the Bibliotheca (1545). This was a huge step in cataloging books. In it, he tried to list every writer who had ever lived. He included their works and short notes about them. This book listed about three thousand authors. It was the first modern bibliography published after the invention of printing. Because of this, Gessner is known as the "father of bibliography." It included about twelve thousand book titles.

A second part of this work came out in 1548. It was a thematic index. It was supposed to have 21 parts, but only 19 were finished. The part about his medical work was never done. The last part, about theology, was published separately in 1549.

The Animal Encyclopedia: Historia animalium

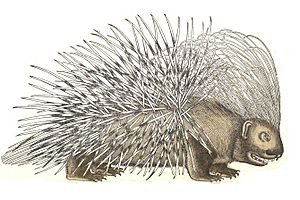

Gessner's huge zoological book was called Historia animalium. It was a 4,500-page encyclopedia about animals. It was published in Zürich in four volumes between 1551 and 1558. These volumes covered:

- Animals with four legs that give birth to live young (like mammals).

- Animals with four legs that lay eggs (like reptiles and amphibians).

- Birds.

- Fish.

A fifth volume about snakes came out in 1587. A German version of the first four volumes was published in 1563. This book is seen as the first modern book on zoology. It connected old ideas with new scientific thinking.

In Historia animalium, Gessner combined information from old sources. These included the Old Testament, Aristotle, and old stories. But he also added his own observations. He created a new, detailed description of the Animal Kingdom. He was the first to try to describe many animals accurately. The book had hand-colored woodcut pictures. These were drawn from what Gessner and his friends actually saw.

Gessner tried to tell the difference between facts and myths. He was known for drawing animals very accurately. But he also included many made-up animals. These included the Unicorn and the Basilisk. He had only heard about these from old stories. However, when Gessner wasn't sure about something, he said so clearly. Besides how useful plants or animals might be, Gessner also wanted to learn about them for moral lessons. He even wrote as much detail about unreal animals as he did about real ones.

Historia animalium has drawings of many well-known animals. It also has drawings of fictional ones, like unicorns and mermaids. Gessner was able to do so much because he knew many leading naturalists across Europe. They sent him their ideas, plants, animals, and gems. He would return the favor by naming plants after them.

His Plant Studies: Historia plantarum (Unfinished)

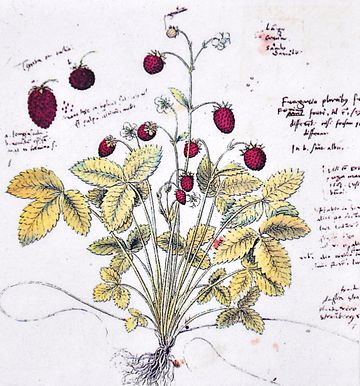

Throughout his life, Gessner collected many plants and seeds. He also took lots of notes and made wood engravings. In the last ten years of his life, he started his main plant book. It was called Historia plantarum. He died before he could finish it. But his notes and drawings were used by many other writers for the next two hundred years. These included about 1,500 drawings of plants, flowers, and seeds. Most of these were original.

The size and scientific detail of his work were unusual for his time. Gessner was a skilled artist. He made detailed drawings of specific plant parts. These showed their features. He also added many notes about how they grew and where they lived. Finally, the complete work was published in 1754.

Censorship and Challenges

There were strong religious tensions when Historia animalium came out. The Pope's list of forbidden books, the Pauline Index, believed that if an author was Protestant, all their books were bad. Since Gessner was a Protestant, his books were put on this list.

Even with these tensions, Gessner remained friends with people on both sides. Catholic booksellers in Venice even protested the ban on his books. Some of his work was eventually allowed after it was "cleaned" of any religious errors.

Conrad Gessner's Lasting Impact

Gessner is called the father of modern scientific botany and zoology. He is also known as the father of modern bibliography. During his time, people knew him best as a botanist. Even with his travels and gardens, Gessner likely spent most of his time in his huge library.

For his History of Animals, he used information from over 80 Greek authors and 175 Latin authors. He also used works by German, French, and Italian writers. He even tried to create a "universal library" of all books ever written. This might sound strange today, but Gessner put a lot of effort into it. He searched through old libraries and book catalogs. By putting together this "universal library," Gessner created a database centuries before computers existed. He would cut out important parts from books. Then he grouped them by theme and put them in boxes. This way, he could find and arrange the information easily. One writer called him "a one-man search engine, a 16th-century Google."

His friends called him "the Swiss Pliny." Legend says that when he knew he was dying, he asked to be taken to his library. He wanted to die among his favorite books. When he died, Gessner had published 72 books. He also had 18 more books that were not yet published. His work on plants was not published until hundreds of years after his death.

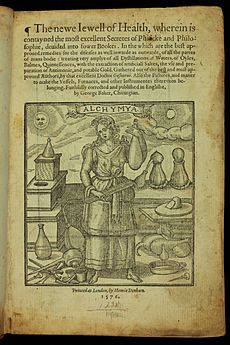

In 1576, George Baker translated one of Gessner's works into English. It was called The Newe Jewell of Health. One of Gessner's students was Felix Plater. He became a medicine professor. Plater collected many plant samples and animal drawings used in Historiae animalium. A year after Gessner died, his friend Josias Simler wrote a book about his life.

Gessner and others started a group in Zurich to study natural sciences. This group later became the Naturforschende Gesellschaft in Zürich (NGZH) in 1746. It is one of the oldest scientific societies in Switzerland. In 1966, the society dedicated its yearly publication to Gessner. This was to celebrate 400 years since his death.

Things Named After Gessner

In 1753, Carl Linnaeus named the main type of tulip, Tulipa gesneriana, after him. The flowering plant genus Gesneria and its family Gesneriaceae are also named after him. There is even a group of moths called Gesneria named in his honor.

Places Remembering Gessner

- The Gessner herbal garden at the Old Botanical Garden, Zürich, is named after him. There is also a statue of him there.

- The cloister in the Grossmünster church, where Gessner is buried, also has a herbal garden dedicated to him.

- Gessner's picture was on the 50 Swiss francs banknotes. These were used between 1978 and 1994.

- On March 16, 2016, the State Museum in Zürich had a special exhibit about Gessner. This was to celebrate his 500th birthday.

See also

In Spanish: Conrad Gessner para niños

In Spanish: Conrad Gessner para niños

- Bibliotheca universalis

- Historia Animalium

- Historia Plantarum

- History of botany

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |