Pierre André Latreille facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pierre André Latreille

|

|

|---|---|

Pierre André Latreille

|

|

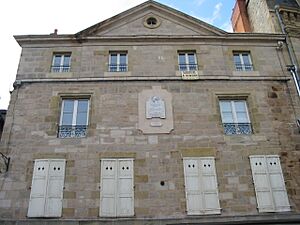

| Born | 29 November 1762 Brive-la-Gaillarde, France

|

| Died | 6 February 1833 (aged 70) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Entomology, arachnology, carcinology |

| Institutions | Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Latreille |

Pierre André Latreille (born November 29, 1762 – died February 6, 1833) was a French zoologist. He was an expert in studying arthropods, which are creatures like insects, spiders, and crabs.

Before the French Revolution, Latreille trained to be a Roman Catholic priest. He was later put in prison. He only got his freedom back because he recognized a rare beetle species he found in his prison cell. This beetle was called Necrobia ruficollis.

In 1796, he published his first important book, Précis des caractères génériques des insectes. Eventually, he started working at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History) in Paris. His amazing work on how to classify and name arthropods earned him a lot of respect. He was even asked to write the insect part of George Cuvier's huge book, Le Règne Animal (The Animal Kingdom). This was the only part not written by Cuvier himself.

Latreille was known as the best entomologist (insect scientist) of his time. One of his students even called him "the prince of entomologists."

Contents

Biography of Pierre André Latreille

Early Life and Studies

Pierre André Latreille was born on November 29, 1762, in a town called Brive-la-Gaillarde in France. He was born to parents who were not married and was abandoned at birth. The name "Latreille" was officially given to him in 1813.

From a very young age, Latreille was like an orphan. But he had helpful people who looked after him. First, a doctor, then a merchant, and later a baron helped him. The baron brought him to Paris in 1778.

He first studied in Brive and then in Paris at the Collège du Cardinal-Lemoine, which was part of the University of Paris. He was studying to become a priest. He joined the Grand Séminaire of Limoges in 1780 and became a deacon in 1786. Even though he was qualified to preach, Latreille later said he never worked as a minister.

Even while he was studying, Latreille became very interested in natural history. He visited the Jardin du Roi (King's Garden) and enjoyed catching insects around Paris. He learned about botany (the study of plants) from René Just Haüy. This helped him meet other important scientists like Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.

The Beetle That Saved His Life

After the French Revolution began, a new law was made in 1790. This law required priests to promise loyalty to the state. Latreille did not take this oath. Because of this, he was put in prison in November 1793 and faced the threat of execution.

One day, the prison doctor was checking on the prisoners. He was surprised to see Latreille closely examining a beetle on the floor of his cell. Latreille explained that it was a rare insect. The doctor was impressed and sent the beetle to a 15-year-old local naturalist named Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent.

Bory de Saint-Vincent knew about Latreille's scientific work. He managed to arrange for Latreille and one of his cell-mates to be released from prison. Latreille and Bory de Saint-Vincent became lifelong friends. The beetle, Necrobia ruficollis, had been described by another scientist, Johan Christian Fabricius, in 1775. Recognizing this beetle likely saved Latreille's life, as all the other prisoners in his cell died within a month.

After his release, Latreille worked as a teacher and wrote letters to other insect scientists, including Fabricius. In 1796, with Fabricius's encouragement, Latreille published his book Précis des caractères génériques des insectes using his own money.

He was briefly put under house arrest in 1797, and his books were taken away. But important scientists like Georges Cuvier, Bernard Germain de Lacépède, and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck helped him. They all worked at the new Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. In 1798, Latreille was hired by the Muséum. He worked with Lamarck, taking care of the arthropod collections, and published many scientific books.

Working at the Museum

When the entomologist Guillaume-Antoine Olivier died in 1814, Latreille took his place as a member of the Académie des sciences de l'Institut de France. In the next few years, Latreille was very busy. He wrote important papers for the Mémoires du Muséum. He also wrote the entire section on arthropods for George Cuvier's famous book, Le Règne Animal ("The Animal Kingdom," 1817). He also wrote hundreds of entries about insects for the Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle.

In 1819, Latreille was chosen as a member of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. As Lamarck, his colleague, became blind, Latreille took on more and more of his teaching and research work. In 1821, Latreille was made a knight of the Légion d'honneur, a very important award in France. In 1829, he took over Lamarck's position as professor of entomology.

Later Years and Legacy

From 1824, Latreille's health started to get worse. He gave his lectures to Jean Victoire Audouin and hired several assistants for his research. These assistants included Amédée Louis Michel Lepeletier, Jean Guillaume Audinet-Serville, and Félix Édouard Guérin-Méneville. He also played a key role in starting the Société entomologique de France (Entomological Society of France) and was its first honorary president.

Latreille's wife became ill in 1830 and passed away in May of that year. The exact date of Latreille's marriage is not clear. He had asked to be released from his promise not to marry as a priest, but his request was never officially answered. He left his job at the museum on April 10, 1832. He wanted to move to the countryside to avoid the cholera epidemic happening in Paris. He came back to Paris in November and died on February 6, 1833, from a bladder disease. He did not have any children of his own, but he had adopted a niece who survived him.

Honoring Latreille

The Société entomologique (Entomological Society) collected money to build a monument for Latreille. This monument was placed over Latreille's grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. It is a 9-foot tall stone pillar with writings on it. One of the inscriptions honors the beetle that saved Latreille's life: "Necrobia ruficollis Latreillii salvator" (meaning "Necrobia ruficollis, Latreille's saviour").

Many books were dedicated to Latreille because of how highly he was thought of. Between 1798 and 1850, as many as 163 species were named in his honor. Some of the groups of animals named after Latreille include:

- Lumbrineris latreilli

- Cecrops latreillii

- Apseudes latreillii

- Orbinia latreillii

- Latreillia

- Cilicaea latreillei

- Bittium latreillii

- Macrophthalmus latreillei

- Eurypodius latreillei

- Sphex latreillei

Latreille's Scientific Work

Latreille did a lot of important scientific work in many different areas. Johan Christian Fabricius called him "the foremost entomologist of our time." Jean Victoire Audouin called him "the prince of entomology."

Classifying Animals

Latreille was very important because he was the first person to try to classify arthropods in a natural way. His "eclectic method" of classifying animals used information from all available features. He did not assume any pre-set goals. Latreille often disagreed with ideas that put humans at the center of everything or believed in a specific purpose for nature.

Besides naming many species and countless genera (groups of species), Latreille also named many larger groups of animals. These include Thysanura (bristletails), Siphonaptera (fleas), Ostracoda (seed shrimp), Stomatopoda (mantis shrimp), Xiphosura (horseshoe crabs), and Myriapoda (millipedes and centipedes).

Naming Rules for Species

Even though Latreille named many species, he was most interested in describing genera (groups of species). He came up with the idea of a "type species." This is a specific species that is the main example for a genus name.

He also liked the idea of naming families of animals after one of the genera in that family. This was instead of naming them after a common feature of the group. This way, a "type genus" was implicitly chosen for the family.

See also

In Spanish: Pierre André Latreille para niños

In Spanish: Pierre André Latreille para niños