René Just Haüy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

René Just Haüy

|

|

|---|---|

René Just Haüy

|

|

| Born | 28 February 1743 Saint-Just-en-Chaussée, France

|

| Died | 1 June 1822 (aged 79) Paris, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | mineralogist |

René Just Haüy (born February 28, 1743 – died June 1, 1822) was a French priest and a scientist who studied minerals. People often called him the Abbé Haüy because he became an honorary priest at Notre Dame Cathedral.

Haüy made amazing discoveries about how crystals are built. His important book, Traité de Minéralogie (1801), helped him become known as the "Father of Modern Crystallography." During the French Revolution, he also helped create the metric system we use today.

Contents

About René Just Haüy

His Early Life

René-Just Haüy was born in a town called Saint-Just-en-Chaussée, France, on February 28, 1743. His parents, Just Haüy and Magdeleine Candelot, were not wealthy; his father was a linen-weaver.

René-Just loved the church's music and services. This caught the attention of a local church leader, who helped him get a scholarship to the College of Navarre in Paris. Haüy worked hard and became a teacher there in 1764. He also studied to become a priest and was ordained in 1770.

Later, Haüy taught at another college. He became friends with a spiritual guide, Abbé Lhomond, who first got him interested in botany (the study of plants). After hearing a lecture by a scientist named Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, Haüy became fascinated by mineralogy (the study of minerals).

René-Just Haüy's brother, Valentin Haüy, was also famous. He started the first school for blind people in Paris.

How He Studied Crystals

A lucky accident led René-Just Haüy to his big discovery about crystallography, which is the science of crystals. He was looking at a broken piece of calcite (a type of mineral). Some say he dropped it, and it broke in a special way. He noticed the broken surface was perfectly smooth.

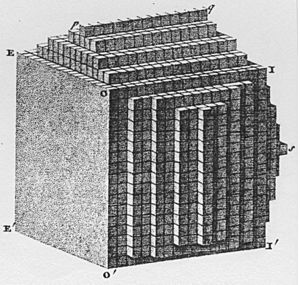

This observation made Haüy curious. He started breaking crystals into the smallest pieces possible. He realized that every type of crystal has a basic, tiny building block, which he called an "integrant molecule." This tiny piece could not be broken down further without changing what the crystal was.

Haüy figured out that crystals grow by stacking these tiny building blocks in orderly layers, following specific geometric rules. This idea helped scientists understand why crystals have their unique shapes. For example, he showed that some minerals that looked similar were actually different because their basic building blocks were shaped differently.

Scientists quickly saw how important Haüy's discovery was. He and other scientists of his time used tools like the goniometer to measure the angles of crystal faces. This helped them understand the outside shape of crystals. The inside structure of these tiny building blocks could not be seen until X-Ray diffraction technology was invented much later.

Between 1784 and 1822, Haüy wrote over 100 reports about his ideas. His main work, Traité de minéralogie (1801), became a very important book in the field. In this book, he described all known minerals, grouping them by their chemical and geometric properties. He also made many pear-wood models of crystals to help teach others about his discoveries.

Haüy also studied pyroelectricity. This is when certain crystals, like tourmaline, create a small electric charge when they are heated. He noticed that the electricity was strongest at the ends of the crystal.

In 1783, Haüy became a member of the French Academy of Sciences.

During the French Revolution

During the French Revolution, Haüy faced difficulties because he was a priest. He refused to take a special oath required by the new government and was put in prison in 1792. Luckily, a friend, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, helped him get released just before many other priests were harmed.

The French Academy of Sciences was temporarily closed during the Revolution. However, before it closed, Haüy played a key role in creating the metric system. He worked with other scientists, including Antoine Lavoisier, to figure out the exact weight of a kilogram. This was a big step towards having standard weights and measures across France.

Even though there was a lot of political trouble, Haüy continued his work. He became the first curator of the Cabinet of Mineralogy in Paris, which is now the Musée de Minéralogie. He also became a professor of physics and later a professor of mineralogy at the National Museum of Natural History.

Napoleon admired Haüy's work. He made Haüy an honorary priest at Notre Dame and gave him one of the first Légion d'Honneur awards. Napoleon even read Haüy's physics book while he was exiled on the island of Elba.

After Napoleon's time, Haüy lost his teaching positions. He spent his last years in poverty and passed away in Paris on June 1, 1822.

His Legacy and Recognition

René-Just Haüy's work was recognized around the world. He was elected an honorary member of the New York Academy of Sciences in 1817 and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1821.

His name is one of the 72 names carved on the Eiffel Tower, honoring important French scientists and engineers.

A mineral called Haüyne was named after him in 1807.

In 2022, the International Mineralogical Association declared it the International Year of Mineralogy to honor the 200th anniversary of René-Just Haüy's death. Many events took place in Paris to celebrate his life and discoveries, including exhibitions and symposiums. A new website was also created to share more about his life, work, and collections.

His Main Books

Here are some of the most important books Haüy wrote:

- Essai d'une théorie sur la structure des crystaux (1784) (Essay on a Theory of Crystal Structure)

- Traité de minéralogie (5 volumes, 1801) (Treatise on Mineralogy)

- Traité élémentaire de physique (2 volumes, 1803, 1806) (Elementary Treatise on Physics)

- Traité des pierres précieuses (1817) (Treatise on Precious Stones)

- Traité de cristallographie (2 volumes, 1822) (Treatise on Crystallography)

He also wrote many articles for science journals.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: René Just Haüy para niños

In Spanish: René Just Haüy para niños

- Centered octahedral number

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |