Mapuche history facts for kids

The Mapuche people, who live in southern Chile and Argentina, have a very old history. Their culture dates back to about 600–500 BC. When the Spanish arrived in the mid-1500s, Mapuche society changed a lot. They started using new crops and animals from Europe. They also traded a lot with the Spanish. Even with all these changes, the Mapuche were never fully taken over by the Spanish Empire.

Between the 1700s and 1800s, Mapuche culture and people spread east into the Pampas and Patagonian plains. This huge new land helped Mapuche groups control a big part of the salt and cattle trade in South America.

Later, from 1861 to 1883, Chile fought many battles to end Mapuche independence. Thousands of Mapuche people died from fighting, stealing, hunger, and diseases like smallpox. Argentina fought similar battles in the 1870s on the other side of the Andes mountains. In many Mapuche areas, their traditional way of life collapsed. This forced thousands to move to big cities, where they lived in poor conditions, working as housemaids, street sellers, or laborers.

Since the late 1900s, Mapuche people have been working hard to get their land rights and indigenous rights recognized.

Contents

Mapuche History Before Europeans Arrived

How the Mapuche People Began

Archaeological discoveries show that the Mapuche culture existed in Chile as early as 600 to 500 BC. Mapuche people are genetically different from other native groups in Patagonia. This suggests they might have come from a different place or were separated for a long time.

Scientists have different ideas about where the Mapuche language, Mapudungun, comes from. Some think it might be related to ancient Mayan languages or other languages from South America and even faraway places like Easter Island!

One idea is that the Mapuche moved to Chile from the Pampas, east of the Andes. Another idea suggests early Mapuche lived near the coast because of all the food from the sea, and only later moved inland.

How Tiwanaku Culture Influenced Mapuche Life

Around 1000 CE, a big empire called Tiwanaku collapsed. Some people think this caused a wave of migration south, which led to changes in Mapuche society in Chile. This might be why the Mapuche language has many words from the Puquina language, like antu (sun) and ñuque (mother).

Experts like Tom Dillehay believe that the fall of Tiwanaku also helped spread farming methods to Mapuche lands in south-central Chile. These methods included special raised fields near Budi Lake and canalized fields in the Lumaco Valley. This connection might also explain why Mapuche stories about the universe are similar to those of people in the Central Andes.

Did Mapuche People Meet Polynesians?

In 2007, some interesting clues appeared that suggested people from Polynesia (islands in the Pacific Ocean) might have met the Mapuche before Christopher Columbus arrived. Chicken bones found in a Mapuche area were dated to between 1304 and 1424. The DNA from these bones matched chickens from places like American Samoa and Tonga, not European chickens. However, a later study said the chicken DNA was more like European or Asian chickens, so this idea is still debated.

Also in 2007, human skulls with Polynesian features were found in a museum. These skulls came from people on Mocha Island, an island near the Chilean coast, where Mapuche people live today. Scientists are hoping to do more research there to find out if Polynesians really did visit.

Some Mapuche words are similar to words in the Rapa Nui language from Easter Island, like toki (axe) and kuri (black). Even a Mapuche hand club, called a clava, looks very similar to a Maori club from New Zealand called a wahaika.

Mapuche Expansion into Chiloé

One idea is that the Cunco people settled on Chiloé Island long ago because they were pushed south by other Mapuche groups. Many place names in Chiloé have words from the Chono language, even though the main language there when the Spanish arrived was Mapuche. This suggests that the Chono people might have lived there first and were later pushed south by Mapuche groups.

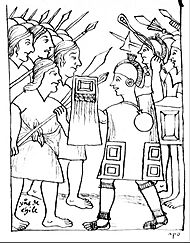

How the Inca Empire Influenced Mapuche Lands

The Inca Empire's troops are said to have reached the Maule River and fought a battle with Mapuche people there. Most experts believe the Inca Empire's southern border was somewhere between Santiago and the Maule River. Some old Spanish writers even claimed the Incas went as far south as the Bío Bío River.

The main Inca settlements in Chile were along the Aconcagua, Mapocho, and Maipo rivers. The Incas had special settlements and forts, and they sometimes allied with local tribes. Some Mapuche people in the Aconcagua Valley learned to speak both Mapudungun and the Inca language, Quechua.

Archaeologists think that Inca workers might have mined gold south of the Inca border, in Mapuche lands. This suggests that the Incas might have wanted to expand into Mapuche territory to get gold. Some early Mapuche pottery found in Valdivia also looks like Inca designs.

Mapuche people wore gold and silver jewelry when the Spanish arrived. This could have been gifts from the Incas, things taken from defeated Incas, or Mapuche people learning Inca metalworking skills. Their contact with the Incas was the first time Mapuche people met a society with a big, organized government. This contact helped them feel like a united group against outsiders, even though they didn't have a single government themselves.

Mapuche Society When the Spanish Arrived

Mapuche Population and Settlements

When the first Spanish arrived in Chile, most native people lived in the Mapuche heartland, from the Itata River to the Chiloé Archipelago. Historians estimate that between 705,000 and 900,000 Mapuche lived there in the mid-1500s.

Mapuche people lived in small villages, mostly along the big rivers of Southern Chile. They often built their homes on hills or isolated spots instead of flat plains.

Mapuche Beliefs and Traditions

The machi (shaman), usually an older woman, is very important in Mapuche culture. The machi performs ceremonies to ward off evil, bring rain, and cure illnesses. They know a lot about Chilean medicinal plants, which they learn during a long training. Many Chileans, no matter their background, use these traditional Mapuche herbs. The main healing ceremony performed by the machi is called the machitun.

Wampu canoes were used in funerals and are part of Mapuche stories about death.

How Mapuche Society Was Organized

Before and during the early Spanish contact, Mapuche politics, economy, and religion were based on family groups called lov. Several lov formed a larger group called a rehue. Each family group had its own way of dealing with others, sometimes aggressive, sometimes peaceful. Family lines were traced through the father, and new wives usually moved to their husband's family home. Having more than one wife was common among Mapuche men. This, along with women marrying outside their own family group, helped unite the Mapuche into one people.

Early Mapuche had two types of leaders: everyday leaders and religious leaders. Later, everyday leaders were known as lonko (chiefs) or toki (war leaders).

Mapuche Economy and Daily Life

In South-Central Chile, most Mapuche groups farmed small clearings in the forests. Some Mapuche used a "slash-and-burn" method for farming. Others, around Budi Lake and in the Lumaco and Purén valleys, used more advanced methods like raised fields and canalized fields. Potatoes were the main food for most Mapuche, especially in the southern and coastal areas where corn didn't grow well. Most Mapuche people worked in farming. They also grew quinoa.

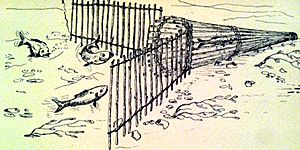

Mapuche and Huilliche people also raised Araucana chickens and chilihueque (a type of llama). They gathered seeds from Araucaria araucana trees and Gevuina avellana plants. The southern coast had lots of shellfish, algae, crabs, and fish, and Mapuche were skilled fishers. Hunting was also common. The forests provided wood for fires and building.

Before the Spanish arrived, Mapuche territory had a good system of roads, which helped the Spanish conquerors move quickly.

Mapuche Tools and Technology

Mapuche tools were usually simple, made from wood, stone, or sometimes copper or bronze. They used many tools made from pierced stones. Volcanic rock was often used because it was easy to shape. Mapuche used single digging sticks and large, heavy, trident-like plows that needed many men to use for farming. They also used maces to break up soil and flatten the ground.

Mapuche canoes, called wampu, were made from hollowed-out tree trunks. In the Chiloé Archipelago, another type of boat called a dalca was common. Dalcas were made of planks and used for sea travel, while wampus were for rivers and lakes.

In the 1500s, there were reports of Mapuche people wearing gold ornaments. Gold was the most important metal in Mapuche culture before the Spanish arrived.

Early Spanish Period (1536–1598)

First Meetings (1536–1550)

The Spanish came to Chile after conquering Peru. Diego de Almagro led a large group to Chile in 1536. He sent Gómez de Alvarado south, who fought with local Mapuche at the Battle of Reynogüelén. Almagro's group then went back to Peru because they didn't find the riches they hoped for.

Another conqueror, Pedro de Valdivia, arrived in 1541 and founded Santiago. In 1544, a captain explored the coast south to 41° S. The northern Mapuche, also called Promaucaes or Picunches, tried to stop the Spanish but didn't succeed. Many northern Mapuche left their good farming lands and moved to remote areas to avoid the Spanish. The Spanish saw this as a way to make them leave Chile. Some Mapuche stopped farming for more than five years as a strategy. This caused problems for the Spanish, but it didn't force them out of Central Chile.

War with the Spanish (1550–1598)

In 1550, Pedro de Valdivia wanted to control all of Chile. He traveled south to conquer Mapuche territory. Between 1550 and 1553, the Spanish founded several cities in Mapuche lands, including Concepción, Valdivia, and Villarrica. They also built forts. The Spanish wanted to control the areas around the Cordillera de Nahuelbuta to mine gold using unpaid Mapuche labor.

After these first conquests, the Arauco War began. This was a long period of fighting between the Mapuche and the Spanish. The Mapuche didn't have a tradition of forced labor like other groups the Spanish had met, and they refused to serve the Spanish. The Spanish, especially those from certain parts of Spain, were also very violent. From 1550 to 1598, the Mapuche often attacked and surrounded Spanish cities. The war was mostly a low-level conflict.

The Mapuche, led by brave leaders like Caupolicán and Lautaro, managed to kill Pedro de Valdivia at the Battle of Tucapel in 1553. However, a typhus disease, a drought, and a famine stopped the Mapuche from pushing the Spanish out in 1554 and 1555. Between 1556 and 1557, Lautaro tried to reach Santiago to free Central Chile, but he was killed in an ambush in 1557.

The Spanish regrouped under Governor García Hurtado de Mendoza (1558–1561). They managed to kill Caupolicán and Galvarino, two important Mapuche leaders. During this time, the Spanish rebuilt cities that had been destroyed and founded new ones like Osorno and Cañete. In 1567, the Spanish conquered the Chiloé Archipelago, where the Huilliche people lived.

Fighting in Araucanía became more intense in the 1590s. The Mapuche of Purén and Tucapel became known for their fierce fighting skills. This helped them unite other Mapuche groups against the Spanish.

Mapuche Adaptations to War

In their early battles with the Spanish, the Mapuche didn't have much success. But over time, the Mapuche of Arauco and Tucapel learned to use horses and gather large numbers of fighters to defeat the Spanish. They learned from the Spanish to build forts on hills. They also dug traps for Spanish horses and used helmets and wooden shields against Spanish guns. Mapuche warfare changed to include guerrilla tactics, like ambushes. The killing of Pedro de Valdivia in 1553 marked a change from the Mapuche's older traditions of ritual warfare.

Mapuche organization changed because of the war. A new, larger political group called the aillarehue, made up of several rehue, appeared in the late 1500s. This larger organization continued into the early 1600s with the butalmapu, which included several aillarehues. This meant the Mapuche achieved a "super-local level of military unity" without having a state government. By the late 1500s, a few powerful Mapuche war leaders had emerged near the Spanish border.

Changes in Population Patterns

The Mapuche population decreased after contact with the Spanish. Diseases and the war with the Spanish killed many people. Others died in Spanish gold mines. Evidence suggests that the Mapuche in the Purén and Lumaco valleys started living in denser villages as a response to the war. The declining population meant that as farming decreased, many open fields in southern Chile became overgrown with forest.

By the 1630s, some Mapuche from the Aconcagua Valley had moved north to other areas, seemingly on their own. In the late 1500s, the Picunche people slowly began to lose their native identity. They left their villages and moved to Spanish farms, where they mixed with other native groups brought from Peru, Tucumán, and other parts of Chile. Because they were few in number, disconnected from their lands, and mixed with others, the Picunche and their descendants lost their original identity.

Independence and War (1598–1641)

Fall of the Spanish Cities

A major event happened in 1598. A group of warriors from Purén, led by Pelantaro, ambushed and killed the Spanish governor, Martín García Óñez de Loyola, and all his troops. It's not clear if it was an accident or if they had followed them.

In the years after this battle, a big uprising happened among the Mapuche and Huilliche. Spanish cities like Angol, Imperial, Osorno, Valdivia, and Villarrica were either destroyed or abandoned. Only Chillán and Concepción managed to survive the Mapuche attacks. Except for the Chiloé Archipelago, all Chilean territory south of the Bío Bío River became free from Spanish rule.

Chiloé also faced Mapuche (Huilliche) attacks. In 1600, local Huilliche joined a Dutch privateer to attack the Spanish settlement of Castro. The Spanish worried that the Dutch might ally with the Mapuche and build a base in southern Chile. They tried to rebuild Valdivia, but the Mapuche wouldn't let them pass through their territory in the 1630s.

Captured Spanish Women

When the Spanish cities fell, thousands of Spanish people were killed or taken captive. One writer from that time said that Mapuche killed over 3,000 Spanish and took over 500 women captive. Many children and Spanish priests were also captured. Skilled workers, Spanish who had left their side, and women were usually spared. The women were often taken to be used by the Mapuche. Some Spanish women were rescued, while others were only freed after a peace agreement in 1641. Some Spanish women even got used to Mapuche life and stayed willingly. These captive women had many children with Mapuche men. These children were not accepted by the Spanish but were welcomed by the Mapuche. This might have helped the Mapuche population grow after being hurt by war and diseases. Taking women captive became a common practice for Mapuche in the 1600s.

Mapuche Adopt New Crops, Animals, and Tools

The Mapuche of Araucanía seemed to pick and choose which Spanish technologies and species to adopt. This meant that their way of life mostly stayed the same after Spanish contact. Their limited adoption of Spanish technology has been seen as a way of cultural resistance.

Mapuche quickly adopted horses and started growing wheat from the Spanish. In the Chiloé Archipelago, less wheat was grown because of the climate. Instead, the Spanish introduction of pigs and apple trees was very successful there. Pigs did well because of the many shellfish and algae exposed by the large tides.

Before the Spanish arrived, Mapuche had chilihueque (llama) livestock. The introduction of sheep caused some competition between the two animals. By the mid-1600s, both coexisted, but there were many more sheep than chilihueques. By the late 1700s, only a few Mapuche groups still raised chilihueques.

Gold mining became forbidden among Mapuche during colonial times, often with the threat of death.

Jesuit Missionaries

The first Jesuits arrived in Chile in 1593 to convert the Mapuche of Araucanía to Christianity. A Jesuit priest named Luis de Valdivia believed Mapuche could only be converted if there was peace. He helped create a "Defensive War" policy, which meant the Spanish would not attack the Mapuche. Luis de Valdivia also took away the wives of a war leader named Anganamón because the Catholic church was against having multiple wives. Anganamón got revenge by killing three Jesuit missionaries in 1612. This didn't stop the Jesuits, who continued their work until they were expelled from Chile in 1767. They worked from Spanish cities and went on missions into Mapuche lands. They didn't set up permanent missions in free Mapuche lands during the 1600s or 1700s. To convert the Mapuche, Jesuits studied their language and customs. Despite their political influence in the early 1600s, the Jesuits had little success in converting the Mapuche.

Slavery of Mapuche People

The Spanish Crown had forbidden the formal slavery of native people. However, the Mapuche uprising from 1598–1604, which led to the destruction of Spanish cities, caused the Spanish to declare in 1608 that Mapuche caught in war could be legally enslaved. Rebellious Mapuche were seen as having turned away from Christianity, so they could be enslaved according to the church's rules at the time. This law made Mapuche slavery, which was already happening, official. Spanish slave raids became more common during the Arauco War. Mapuche slaves were sent north to other cities like La Serena and Lima. Slavery for Mapuche "caught in war" was finally abolished in 1683. By then, free mixed-race workers had become much cheaper than owning slaves, suggesting that economic reasons played a part in ending slavery.

Age of Parliaments (1641–1810)

During this period, the Spanish and Mapuche often held meetings called "Parliaments" to make peace agreements.

Mapuche Expansion and Influence

The Mapuche people expanded their influence and culture into new areas, especially towards the east into the Pampas and Patagonia. This process is known as Araucanization.

Republican Period (1810–1990)

Mapuche Role in Chile's Independence War (1810–1821)

On October 24, 1811, Mapuche chiefs were invited to Concepción by the new government that had taken power in Chile. About 400 Mapuche warriors attended and learned about the new political changes. Even though they probably didn't know much about the big political changes in the Spanish Empire, the warriors declared their loyalty to the new government.

During the "Guerra a muerte" (War to the Death) phase of the Chilean War of Independence, there was a lot of fighting between different Mapuche groups. Some supported the Spanish king (royalists), and others supported the Chilean independence fighters (patriots). It's thought that their support was more about immediate benefits than strong political beliefs. Long-standing rivalries between Mapuche chiefs date back to this time.

Living Alongside the Republic of Chile (1821–1861)

Mapuche lands south of the Bío-Bío River began to be bought by non-Mapuche people in the late 1700s. By 1860, most of the land between the Bío-Bío and Malleco rivers was controlled by Chileans. A boom in Chilean wheat farming increased the pressure to buy land in Araucanía, leading to many tricks and frauds against the Mapuche. A few land speculators gained control of huge areas through fraud and kept them with the help of armed men.

The increasing number of settlers moving into Mapuche territory from the north, and the arrival of German settlers in the south, led chief Mañil in 1859 to call for an uprising to protect their land. Most Mapuche answered his call, except for some communities who had strong ties with Valdivia. Towns like Angol and Nacimiento were attacked. A peace offer from the settlers was accepted in 1860. The agreement stated that land could only be transferred with the approval of the Mapuche chiefs.

End of Mapuche Independence (1861–1883)

In the 1800s, Chile grew quickly. Chile set up a colony at the Strait of Magellan in 1843, settled Valdivia and Osorno with German immigrants, and gained land from Peru and Bolivia. Later, Chile also took over Easter Island. In this context, Araucanía began to be conquered by Chile for two main reasons: first, Chile wanted its territory to be continuous, and second, it was the only place left for Chilean farming to expand.

Between 1861 and 1871, Chile took over several Mapuche territories in Araucanía. In January 1881, after winning important battles against Peru, Chile continued its conquest of Araucanía.

The Argentine Army's campaigns against Mapuche on the other side of the Andes in 1880 pushed many Mapuche into Araucanía. The fast Argentine advance worried Chilean authorities and contributed to the Chilean-Mapuche conflicts of 1881.

On January 1, 1883, Chile rebuilt the old city of Villarrica, formally ending the occupation of Araucanía.

From Losing Land to Seeking Justice (1883–1990)

Historian Ward Churchill claimed that the Mapuche population dropped from half a million to 25,000 within one generation because of the occupation. The conquest of Araucanía forced many Mapuche to leave their homes and search for shelter and food. Some Chilean forts provided food rations. Until about 1900, the Chilean state gave almost 10,000 food rations monthly to displaced Mapuche. Mapuche poverty was a common topic in Chilean Army writings from the 1880s to around 1900. One scholar says that the introduction of state education during the occupation negatively affected traditional Mapuche education.

In the years after the occupation, the economy of Araucanía changed from raising sheep and cattle to farming and cutting wood. The Mapuche losing their land led to serious soil erosion because they continued to raise many animals in smaller areas.

Recent History (1990–Present)

Many Mapuche people now live across southern Chile and Argentina. Some keep their traditions and continue farming, but most have moved to cities to find better jobs. Many are concentrated around Santiago. Chile's Araucanía Region has a rural population that is 80% Mapuche. There are also many Mapuche in the Los Lagos, Bío-Bío, and Maule regions.

In the 2002 Chilean census, 604,349 people identified as Mapuche. The two regions with the most Mapuche were Araucanía with 203,221, and Santiago with 182,963. These numbers are higher than the total Mapuche population in Argentina in 2004–2005.

In recent years, the Chilean government has tried to fix some past unfairness. In 1993, a law was passed that officially recognized the Mapuche people and seven other native groups, as well as the Mapudungun language and culture. Mapudungun, which was once forbidden, is now taught in elementary schools around Temuco.

Even though Mapuche people make up 4.6% of the Chilean population, few have reached government positions. In 2006, among Chile's 38 senators and 120 deputies, only one identified as indigenous. The number of native politicians in local government is higher.

Representatives from Mapuche organizations have joined the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO) to seek recognition and protection for their cultural and land rights.

Modern Conflicts

Land disputes and violent clashes continue in some Mapuche areas, especially in the northern parts of the Araucanía region. To reduce tensions, a commission in 2003 suggested big changes in how Chile treats its native people, most of whom are Mapuche. The recommendations included officially recognizing political and "territorial" rights for native peoples, and promoting their cultures.

While Japanese and Swiss companies are involved in Araucanía's economy, the two main forestry companies are Chilean-owned. In the past, these companies planted huge areas with non-native trees like Monterey pine and eucalyptus, sometimes replacing native forests. However, such replacement is now forbidden.

Chile exports wood to the United States, mostly from this southern region, with an annual value of $600 million and growing. A conservation group called Forest Ethics (now Stand.earth) led a campaign to protect the forests. As a result, companies like Home Depot agreed to change their buying rules to protect native forests in Chile. Some Mapuche leaders want even stronger protections for the forests.

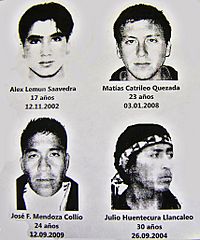

In recent years, actions by some Mapuche activists have been treated under anti-terrorism laws. These laws were first put in place by Augusto Pinochet's military government to control political opponents. The law allows prosecutors to hide evidence from the defense for up to six months and keep witnesses' identities secret. Violent activist groups use tactics like burning buildings and pastures, and making death threats. Mapuche protesters have used these tactics against properties of both large forestry companies and private individuals. In 2010, some Mapuche went on hunger strikes to try and change the anti-terrorism laws.

See also

In Spanish: Historia del pueblo mapuche para niños

In Spanish: Historia del pueblo mapuche para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |