Occupation of Araucanía facts for kids

The Occupation of Araucanía (1861–1883) was a time when the Chilean army and settlers moved into Mapuche lands. This led to the Araucanía region becoming part of Chile. Chilean authorities called this process the Pacification of Araucanía. This event happened at the same time as Argentina's campaigns against the Mapuche and Chile's wars with Spain and Peru/Bolivia.

For a long time, the Mapuche people had successfully resisted Spain and remained independent. After Chile became independent, relations between Chile and the Mapuche were mostly friendly. However, for economic and political reasons, and because some people had negative views of the Mapuche, Chile decided to take control of Araucanía, even if it meant using force.

Mapuche leaders reacted in different ways. Some worked with the Chilean government. Many others, especially the Arribanos, fought against the Chilean soldiers and settlers. Some Mapuche groups chose to stay neutral. For the first ten years (1861–1871), the Mapuche could not stop Chile from advancing. However, they often defeated small Chilean groups and avoided big battles. The next decade was mostly peaceful.

But in March 1881, a large Chilean army moved into the region from the north. They reached the Cautín River, bringing most of the territory under Chilean control. In November 1881, the Mapuche made a final effort to regain their land. They launched attacks on Chilean settlements across the region. Most of these attacks were stopped, and Mapuche forces were defeated quickly. In the following years, Chile made its control over the conquered lands stronger.

This conflict caused many Mapuche people to die from fighting and diseases like smallpox. Many Mapuche also suffered because the Chilean army and bandits stole their belongings. It became hard for them to grow crops. Their economy was badly damaged, and they lost much of their land. This led to widespread poverty that has affected Mapuche families for many generations.

Contents

Why the Occupation Happened

From the late 1700s, trade between Mapuche and Spanish (and later Chilean) people grew. Fighting also decreased. Mapuche people bought goods from Chile and sometimes wore "Spanish" clothes. But even with close contact, Chileans and Mapuche remained different in their societies, politics, and economies.

For the first 50 years after Chile's independence (1810–1860), the government did not focus much on Araucanía. They prioritized developing Central Chile.

Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, an important Chilean figure, once said that between two Chilean provinces, there was a land that was not truly part of Chile. He noted that its language was different, and other people lived there.

Chilean Farms Needed More Land

Chile's farming industry was badly affected by the Chilean War of Independence. But after a "silver rush" began in 1832, farming grew in the northern part of Chile. Another big growth in farming happened from 1848. This was because of a high demand for wheat during the colonization of Australia and the California Gold Rush. Even after these markets disappeared, growing wheat remained very profitable.

By the 1850s, with German settlers arriving in the south and sheep farming starting near the Strait of Magellan, Araucanía was the only place left for Chilean farming to expand.

Non-Mapuche people began buying Mapuche lands south of the Bío-Bío River in the late 1700s. By 1860, most of the land between the Bío-Bío and Malleco River was controlled by Chileans. The demand for wheat made Chileans even more eager to buy land in Araucanía. This led to many dishonest deals and frauds against the Mapuche. Some land buyers gained control of huge areas through fraud. They used armed men to keep their control.

There was a big difference: Chile's economy had a booming farming sector. But a large part of the Mapuche economy relied on raising livestock in one of the biggest territories any indigenous group had in South America.

The Shipwreck of Joven Daniel

In 1849, a ship called Joven Daniel was traveling between Valdivia and Valparaíso. It was wrecked near the coast, between the mouths of the Imperial and Toltén River. A local Mapuche tribe looted the shipwreck, and some survivors were killed.

News of these events first reached Valdivia and then Santiago. This caused strong anti-Mapuche feelings and made people believe that Mapuches were cruel. President Manuel Bulnes's opponents called for a punitive expedition (a military attack to punish). The Mapuches prepared for a fight with the Chilean Army. However, President Bulnes decided against a punitive expedition, seeing it as not important for the eventual conquest of Araucanía.

The 1859 Uprising

Over time, settlers kept moving from the north across the Bío Bío River into Mapuche territory. Also, German settlers appeared in the south of Mapuche land. Because of this, in 1859, Mapuche chief Mañil called for an uprising to protect their territory. Most Mapuches answered his call. However, communities in Purén, Choll Choll, and the southern coastal Mapuches, who had strong ties with Valdivia, did not join.

The towns of Angol, Negrete, and Nacimiento were attacked. In 1860, during a meeting of several Mapuche chiefs, a peace offer from settlers was accepted. The agreement stated that land could only be transferred with the chiefs' approval.

The 1859 uprising made Chileans see the Mapuches as a dangerous threat to the new settlements in Araucanía. This influenced public opinion in Chile, pushing for Araucanía to become fully part of Chile. These events helped Chilean authorities decide to occupy Araucanía.

Planning the Occupation

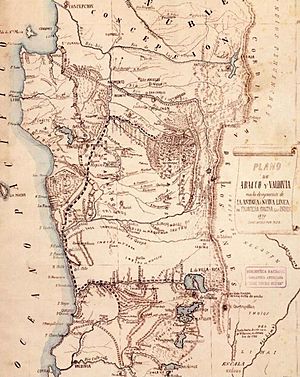

In 1823, Chilean minister Mariano Egaña proposed a plan to Congress. It was to colonize the land between the Imperial River and the Bío Bío River. This plan involved building a series of forts on the northern banks of the Imperial and Cautín Rivers, right in the middle of Araucanía. Chilean president Ramón Freire first adopted this plan. But he was later convinced to focus on expelling the Spanish from Chiloé Archipelago instead, leaving the Araucanía issue for later.

In 1849, Chilean minister Antonio Varas gave a report to the Chilean congress about Araucanía. Varas suggested that a special government system should be created for Araucanía when it eventually became part of Chile. Varas believed the goal was to "civilize" the native people. This meant improving their living standards and teaching them "moral and religious truths."

Manuel Montt, as President of Chile, passed a law on December 7, 1852. This law created the Province of Arauco. This new province was meant to manage all lands south of the Bío-Bío River and north of Valdivia Province. Mapuche chief Mañil wrote a letter to Manuel Montt. He complained about graves being robbed for Mapuche silver, Mapuche houses (ruka) being burned, and other abuses against Mapuches in the new province. Mañil also accused the local leader, Villalón con Salbo, of getting rich by stealing cattle.

The final plan for occupying Araucanía was largely created by Colonel Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez. Saavedra's plan involved the government leading the colonization, similar to the United States frontier. This was different from the old Spanish way of private companies leading colonization in Chile.

His plan included these main points:

- The Chilean Army would advance to the Malleco River and build a defensive line there.

- Government land between the Malleco and Bío Bío Rivers would be divided into plots. These plots would be given to private citizens.

- Araucanía would be settled by Chilean and foreign settlers. Foreign settlers of different nationalities would be gathered in specific places to help them fit in.

- Indigenous peoples were to "enter into reduction and civilization." This meant they would be settled in smaller areas and taught Chilean ways of life.

The Occupation Begins

Chile Moves to Malleco (1861–62)

In 1861, Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez ordered Major Pedro Lagos to move troops to where the Mulchén River meets the Bureo River. A small fort was built there between December 1861 and May 1862. This happened after the local Mapuche chief Manuel Nampai gave up the land. The town of Mulchén grew around this fort. Following an old tradition from colonial times, Saavedra paid salaries to friendly Mapuche chiefs in the Mulchén area.

Saavedra tried to get the Chilean government to approve his plans by offering to resign in December 1861 and again in February 1862.

In 1862, Saavedra advanced with 800 soldiers into the remains of the town of Angol. Other troops strengthened the defenses of Los Ángeles, Negrete, Nacimiento, and Mulchén. Groups of civilians were to defend Purén and Santa Bárbara.

Second Chilean Campaign (1868–1869)

As the Mapuches prepared for war, many moved their families to safe places south of the Cautín River or to Lonquimay. The Abajino chiefs Catrileo and Pinolevi, who had good relations with the Chilean government, refused to join the Mapuche alliance. In 1868, they were killed in a malón (a raid) against them.

In 1868, the Arribano chief Quilapán, son of Mañil, attacked a Chilean outpost at Chihuaihue. A group of Chileans led by Pedro Lagos was attacked while moving to Quechereguas. Another Mapuche group defeated a Chilean Army unit, killing 23 out of 28 soldiers.

Because of these early failures, Commander José Manuel Pinto started a scorched earth strategy in Mapuche lands in the summer of 1869. During these attacks by the Chilean Army, houses and crop fields were looted. More than 2 million livestock animals were stolen from the Mapuches. Some Mapuche civilians, including women and children, were either killed or taken captive. Besides the Chilean Army's looting, bandits also stole Mapuche property with the approval of Chilean authorities. The Mapuches avoided big battles, allowing the Chilean armies to cross their territory. There was a huge difference in weapons: Chileans used repeating rifles, while Mapuches had few firearms and mostly used bolas, spears, and slings.

The war caused a famine among Mapuches in the winter of 1869. A smallpox epidemic made the situation even worse. Some Mapuches sold their few remaining livestock and silver jewelry in towns like La Frontera to get food.

Peace Talks (1869–1870)

In late 1869 and early 1870, Saavedra organized two meetings, one at Toltén and another at Ipinco. At Toltén, Saavedra tried to make agreements with the southern chiefs to isolate Quilapán. The chiefs at the meeting could not agree on whether Saavedra should be allowed to build a town in southern Araucanía. At Toltén, Mapuche chiefs told Saavedra that Orélie-Antoine de Tounens was back in Araucanía. When Orélie-Antoine de Tounens heard that his presence was known, he fled to Argentina. However, he had promised Quilapán to get weapons.

At the meeting in Ipinco, the Abajinos rejected all of Saavedra's proposals. However, the meeting did help weaken the alliance between the Abajino and Arribano groups.

Declared War (1870–1871)

In 1870, the Chilean Army continued its operations against the Mapuches. José Manuel Pinto officially declared war on the Mapuches on behalf of Chile in May 1870. In 1870-1871, Mapuches often moved their families away before the Chilean Army arrived to loot. During the winter of 1870, the Chilean Army continued to burn rukas (Mapuche houses) and steal livestock.

Despite these actions, the situation for many Mapuche worsened. Newspapers reported food shortages. Livestock numbers had dropped, and many Mapuches had not been able to harvest or plant crops for almost three years. Domingo Melín, representing Quilapán, tried unsuccessfully to make a peace agreement with Chile in 1870.

In the summer of 1871, Quilapán gathered an army. This army included Mapuche reinforcements from Argentina. They launched an attack against the fortified Malleco Line and the settlers around it. The Chilean Army pushed back this attack. Their cavalry had recently changed their Minié rifles to Spencer repeating rifles, giving them a clear advantage over the Mapuches.

Quilapán sent a letter in March 1871 to Orozimbo Barbosa, seeking a peace agreement. No agreement was made, but fighting stopped for 10 years (1871-1881). Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez resigned from leading the Army of Operations in Araucanía in 1871 due to political reasons.

A Quiet Period (1871–1881)

During the time after the 1871 war, Mapuches in the Chilean-occupied areas suffered many abuses and even murders by settlers and Chilean soldiers.

Mapuches noticed that Chilean military bases were getting smaller. This was because Chile sent troops north to fight Peru and Bolivia during the War of the Pacific (1879–1883). The apparent weakening of Chile's military presence in Araucanía, along with many abuses, caused the Mapuches to start planning a rebellion.

In 1880, a case of horse theft led to chief Domingo Melín being taken by Chilean troops to Angol for trial. Before reaching Angol, Domingo Melín and some of his relatives were killed by the Chilean military. The Mapuches responded by attacking the fort and village of Traiguén in September 1880. Almost a thousand warriors took part in this attack. This showed that the Mapuches had been preparing for war.

The Argentine Army's campaigns against the Mapuches on the other side of the Andes pushed many Mapuches into Araucanía in 1880. Pehuenche chief Purrán was captured by the Argentine Army. The Argentine Army also entered the valley of Lonquimay, which Chile considered its own territory. The fast Argentine advance worried Chilean authorities. This contributed to the Chilean-Mapuche conflicts of 1881.

Chile Moves to Cautín (1881)

In January 1881, the Mapuches in the Malleco area rose up against the Chilean occupation. The town and forts of Traiguén, Lumaco, and Collipulli were attacked.

Chile had just won important battles against Peru in January 1881. So, Chilean authorities turned their attention back to Araucanía. They wanted to protect the advances they had worked so hard to establish. The goal was not just to defend forts and settlements, but also to move the frontier all the way from the Malleco River to the Cautín River.

Interior minister Manuel Recabarren was appointed by president Aníbal Pinto to oversee this process from the town of Angol. Colonel Gregorio Urrutia was called from Chilean-occupied Lima to Araucanía to lead the Army of the South.

On March 28, Gregorio Urrutia founded the town of Victoria on the banks of the Traiguén River. Recabarren personally led a large group of soldiers that established the forts of Quillem, Lautaro, and Pillalelbún. In Pillalelbún, some Mapuche chiefs approached Recabarren. They asked him not to go beyond the Cautín River. Recabarren replied that the entire territory was being occupied. When Temuco was founded on the northern banks of the Cautín River, Recabarren met chief Venacio Coñoepán and other chiefs from Choll-Choll. They also asked him not to advance further.

With the Chilean advance to the Cautín River, a small mountain range called Cadena de Ñielol remained a place of Mapuche resistance. From there, warriors carried out raids or attacks against easy targets. To stop this, Gregorio Urrutia built a fort in the range.

At first, Mapuches offered little resistance to Chile's advance to the Cautín River. Recabarren believed that Mapuches had not reacted because they expected new forts and towns to be built only after meetings with Chilean authorities.

Mapuche Uprising of 1881

Quick facts for kids Mapuche uprising of 1881 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Mapuche rebels |

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

A series of Mapuche attacks began in late February 1881. This was just a few days after Temuco was founded in the middle of Mapuche territory. The first big attack was against a group of carts carrying injured soldiers from Temuco to Fuerte Ñielol. All 40+ soldiers guarding them and the 96 injured or sick soldiers were killed.

In response, Gregorio Urrutia attacked the Mapuche warriors of Cadena Ñielol. On his way, he burned over 500 rukas and captured over 800 cattle and horses. On the other side of the Andes, Pehuenches attacked the Argentine outpost of Chos Malal in March. They killed all 25-30 soldiers there. In mid-March, Mapuche chiefs met to discuss the situation. They rejected the new Chilean settlements and decided to go to war. They set November 5 as the date for their uprising.

A group of Arribanos attacked the fort of Quillem by mistake on the wrong date, November 3. This put all Chilean bases in Araucanía on alert, and settlers took shelter in the forts. On November 5, Mapuches unsuccessfully attacked Lumaco, Puerto Saavedra, and Toltén. Near Tirúa, Costino warriors suffered heavy losses in two fights with over 400 armed settlers, farmers, and some soldiers. Only Imperial was successfully taken over.

The most important battles happened at the fort of Ñielol and Temuco, which were in the heart of Araucanía. In these places, the rebelling Mapuches could not drive the Chileans and their allies out of their fortified positions.

Not all Mapuche leaders and communities joined the uprising; some sided with Chile. After the uprising was defeated, Mapuche chiefs who rebelled were severely punished. The rukas of Ancamilla and other rebellious chiefs were destroyed.

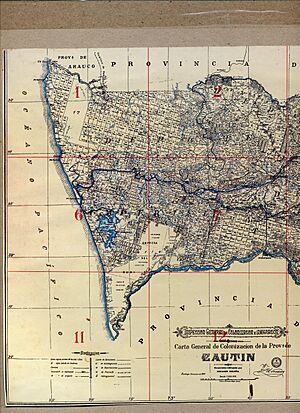

Taking Control of Other Areas (1882–83)

Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez believed that the Mapuches' ability to cross the Andes mountains was one of their main military strengths. To stop Mapuches from freely crossing the Andes and to claim control over the Andean valleys, several expeditions were organized in the summer of 1882. One expedition founded the fort of Nitrito in the Andean valley of Lonquimay. Another founded Cunco near Llaima Volcano. Yet another expedition founded Curacautín in the upper part of the Cautín River.

On January 1, 1883, Chile re-founded the old city of Villarrica. This formally ended the process of occupying Araucanía. Six months later, on June 1, president Domingo Santa María declared:

The country has happily seen the problem of taking control of all Araucanía solved. This event, so important for our society and politics, and so significant for the future of the republic, has ended, happily and with costly and painful sacrifices. Today all Araucanía is under control, not just by military force, but by the moral and civilizing power of the republic...

What Happened Next

Some historians claim that the Mapuche population dropped from half a million to 25,000 in one generation. This was due to the occupation, diseases, and famine. The conquest of Araucanía forced many Mapuches to leave their homes and search for shelter and food. Some Chilean forts helped by giving out food. Until around 1900, the Chilean state provided almost 10,000 food rations each month to displaced Mapuches. Mapuche poverty was a common topic in Chilean Army writings from the 1880s to around 1900.

The Chilean government moved the Mapuche people to nearly three thousand small areas called "títulos de merced." These areas covered about 500,000 hectares of land.

The forts built along the coast became the centers for new towns.

In the years after the occupation, Araucanía's economy changed. It went from being based on raising sheep and cattle to focusing on farming and wood production. The Mapuches lost much of their land after the occupation. This caused serious erosion because they continued to raise many livestock animals in smaller areas.

Chilean and Foreign Settlers

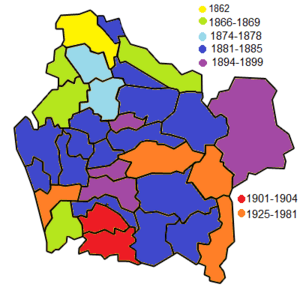

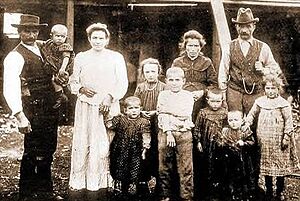

Once Araucanía was under control, the Chilean government encouraged people from Europe to move there.

By 1883, some Chilean thinkers had started to criticize the German settlers in Southern Chile. Chilean minister Luis Aldunate felt that Germans did not fit in well. He thought the country should avoid "exclusive and dominant races monopolizing the colonization." Because of this, after the Occupation of Araucanía, settlers from countries other than Germany were preferred in colonization programs.

The largest groups of settlers were Italians, who mostly settled around Lumaco. Swiss people colonized Traiguén. Boers mainly settled around Freire and Pitrufquén. Other settlers came from England, France, and Germany. Some estimates say that by 1886, there were 3,501 foreign settlers in Araucanía. Another study shows that 5,657 foreign settlers arrived in Araucanía between 1883 and 1890. According to Chile's Agencia General de Colonización, from 1882 to 1897, German settlers made up only 6% of the foreign immigrants to Chile. They were fewer than those from Spain, France, Italy, Switzerland, and England.

At first, Chilean settlers came to Araucanía on their own. Later, the government started to encourage Chileans to settle there. Chilean settlers were mostly poor and often remained so in their new lands.

Education in Araucanía

In 1858, there were 22 public schools in the Province of Arauco. This number grew as a school was built with each new town established in Araucanía. Public education clearly became more important than the older, small missionary school system during the conquest. During the conquest, many Mapuche chiefs were forced to send their sons to study in Chillán or Concepción. In 1888, the province's first high school was established in Temuco. Scholar Pablo Miramán says that introducing state education harmed traditional Mapuche education in Araucanía. The sons of Mapuche chiefs were the main focus of public education.

See also

In Spanish: Ocupación de la Araucanía para niños

In Spanish: Ocupación de la Araucanía para niños

- Araucanization

- Arauco War

- Chilenization of Tacna, Arica and Tarapacá

- Conquest of the Desert

- Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |