Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia

Reino de la Araucanía y la Patagonia

|

|

|---|---|

| November 17, 1860 and November 20, 1860 – January 5, 1862 | |

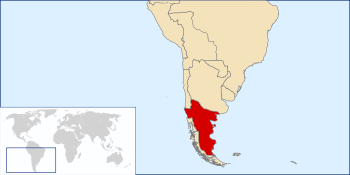

Location of the claimed territory of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia, in Chile and Argentina

|

|

| Status | Unrecognized State |

| Capital | Perquenco (claimed) |

| Common languages | Mapudungun |

| Government | Elective Monarchy |

| King | |

|

• 1860–1862

|

Orélie-Antoine I (Aurelio Antonio I) |

| History | |

|

• Established

|

November 17, 1860 and November 20, 1860 |

|

• Disestablished

|

January 5, 1862 |

| Today part of | Argentina Chile |

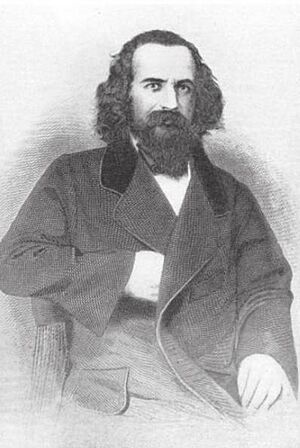

The Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia (Spanish: Reino de la Araucanía y de la Patagonia; French: Royaume d'Araucanie et de Patagonie) was a state that was never officially recognized by other countries. It was declared by a French lawyer and adventurer named Orélie-Antoine de Tounens on November 17 and 20, 1860. He claimed that the lands of Araucanía and eastern Patagonia did not belong to any other country. He then announced himself as the king of these regions.

Antoine de Tounens had some support from Mapuche leaders, called lonkos, in a small part of Araucanía. They hoped he could help them stay independent from the governments of Chile and Argentina. However, Chilean authorities arrested Antoine de Tounens on January 5, 1862. He was put in prison and later declared mentally unwell on September 2, 1862. He was then sent back to France on October 28, 1862. He tried three more times to return to Araucanía to get his "kingdom" back, but he never succeeded.

Contents

History of the Kingdom's Founding

In 1858, Antoine de Tounens, a former lawyer from France, read a book called La Araucana. This book inspired him to travel to Araucanía and try to become its king. He arrived in Chile and traveled south to the Biobío area. There, he met some Mapuche tribal leaders, known as lonkos.

De Tounens promised these leaders weapons and help from France. He said this help would allow them to remain independent from Chile. The Mapuche leaders then chose him as their Great Toqui, which means Supreme Chieftain. They likely believed that having a European person speak for them would help their cause.

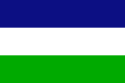

On November 17 and 20, 1860, Antoine de Tounens made two official statements. He declared that the regions of Araucanía and eastern Patagonia were independent. He announced the creation of the Kingdom of Araucanía with himself as King Orélie-Antoine I. He named Perquenco as his kingdom's capital. He also designed a flag and even had coins made for his new nation.

In his writings from 1863, he explained his actions. He wrote, "I took the title of king... On November 17, I returned to Araucania to be publicly recognized as king, which happened on December 25, 26, 27 and 30. Weren't we, the Araucanians, free to give me power, and I to accept it?"

The declaration of this kingdom led to the Occupation of Araucanía by Chilean forces. The Chilean president, José Joaquín Pérez, ordered his commander, Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez, to arrest Antoine de Tounens. This happened on January 5, 1862. Tounens was then imprisoned and declared mentally unwell by a court in Santiago on September 2, 1862. He was sent back to France on October 28, 1862.

Attempts to Return and Concerns in France

In 1870, during a meeting with Mapuche leaders, Commander Saavedra learned that Antoine de Tounens was back in Araucanía. When Orélie-Antoine de Tounens found out his presence was known, he quickly fled to Argentina. However, he had promised a Mapuche leader named Quilapán to get him weapons. There were reports that a shipment of weapons seized in Argentina in 1871 had been ordered by Orélie-Antoine de Tounens.

Around the same time, a French warship, the d'Entrecasteaux, visited a port in Chile. This made Commander Saavedra suspect that France might try to interfere. It seems these fears might have been true. Information given to a Chilean official in 1870 suggested that French Emperor Napoléon III's government had discussed helping the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia against Chile.

On August 28, 1873, a court in Paris ruled that Antoine de Tounens had no valid claim to be a sovereign ruler. He died poor on September 17, 1878, in France. He spent years trying to get his kingdom back, but he never succeeded.

The Kingdom After de Tounens

Historians have called the Kingdom of Araucanía a "curious and semi-comic episode." After Antoine de Tounens died, other people in France, who were not related to him, claimed to be the next "king" or "prince" of Araucanía and Patagonia. For example, a French champagne salesman named Gustave Laviarde took on the title Aquiles I.

These people who claim the "throne" are sometimes called "monarchs of fantasy." Their claims are not legally recognized by any country. However, some journalists have noted that the idea of this symbolic monarchy continues. They say it helps keep alive the memory of Orélie-Antoine and supports the rights of the Mapuche people. The ongoing Mapuche conflict has given this "kingdom" a new purpose for some.

A Mapuche writer named Pedro Cayuqueo believes the kingdom was a missed chance. He thinks that if Araucanía had been ruled by France, the Mapuche people might have had rights similar to the Kanak people in New Caledonia. The Kanak people were given a chance to vote on their independence from France in a 2018 referendum.

People Who Claimed the Throne After Antoine de Tounens

Antoine de Tounens did not have any children. But since his death in 1878, several French citizens, who were not related to him, have claimed to be the next in line for the "throne of Araucania and Patagonia." It is not clear if the Mapuche people themselves accept these claims or are even aware of them.

| No. | Image | Title | Given name (Birth–Death) |

Reign | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Orélie-Antoine I | Orélie-Antoine de Tounens (1825–1878) |

1860–1878 | |

| 2 |  |

Achille I | Gustave-Achille Laviarde (1841–1902) |

1878–1902 | |

| 3 |  |

Antoine II | Antoine-Hippolyte Cros (1833–1903) |

1902–1903 | |

| 4 |  |

Laure Therese I | Laure-Therese Cros (1856–1916) |

1903–1916 | |

| 5 |  |

Antoine III | Jacques Antoine Bernard (1888–1952) |

1916–1952 | |

| 6 |  |

Prince Philippe | Philippe Paul Alexandre Henri Boiry (1927–2014) |

1952–2014 | |

| 7 |  |

Antoine IV | Jean-Michel Parasiliti di Para (1942–2017) |

2014–2017 | |

| 8 |  |

Frédéric I | Frédéric Rodriguez-Luz (1964–) |

2018–present |

See also

In Spanish: Reino de la Araucanía y la Patagonia para niños

In Spanish: Reino de la Araucanía y la Patagonia para niños