Second voyage of HMS Beagle facts for kids

Beagle at Ponsonby Sound in the Beagle Channel, Tierra del Fuego, in March 1834; painting by the ship's draughtsman Conrad Martens

|

|

| Leader | Robert FitzRoy |

|---|---|

| Start | 27 December 1831 |

| End | 2 October 1836 |

| Goal | Survey South American coast |

| Ships | HMS Beagle |

| Achievements | Research leading to Darwin's theory of evolution |

| Route | |

|

|

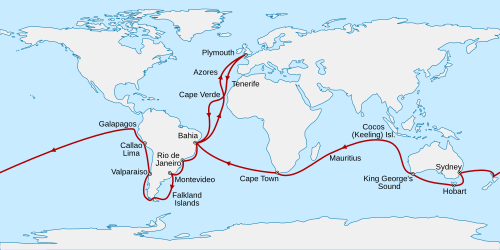

The second voyage of HMS Beagle, from December 27, 1831, to October 2, 1836, was a major survey trip. The ship, HMS Beagle, was led by Captain Robert FitzRoy. He had taken command during the first voyage after the previous captain died. FitzRoy wanted a naturalist on board to study geology and nature.

Charles Darwin, then 22, was a recent graduate who wanted to see the tropics. He joined the ship as a guest. During the trip, he read Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology, which greatly influenced him. By the end of the voyage, Darwin was known as a geologist and fossil collector. His journal, later called The Voyage of the Beagle, made him a famous writer.

The Beagle sailed across the Atlantic Ocean. It then mapped the coasts of southern South America. The ship returned home by way of Tahiti and Australia, completing a trip around the world. Darwin was told the voyage would last two years, but it lasted almost five!

Darwin spent most of his time exploring on land. He was on land for three years and three months, and at sea for 18 months. Early on, Darwin decided to write a geology book. He showed a great talent for developing new ideas. In Argentina, he found huge fossils of extinct mammals. He also collected and studied many plants and animals. His discoveries made him question the idea that species never change. These findings later helped him develop his theory of evolution by natural selection.

Contents

Why the Beagle Sailed

After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, countries like Britain wanted to explore and expand. They needed good maps of sea routes for trade and supplies. Old maps were often wrong. Spain's control over trade in South America had ended. Britain's trade agreement with Argentina in 1825 made the South American coast very important.

The British Navy, called the Admiralty, ordered Commander King to map the southern coasts of South America. Darwin wrote that the trip's goal was to finish mapping Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. It also aimed to map the coasts of Chile, Peru, and some Pacific islands. Another goal was to measure distances around the world using special clocks. The expedition also had a role in diplomacy, visiting areas where different countries had claims.

The Admiralty gave detailed instructions. One main task was to fix errors in earlier maps about the longitude of Rio de Janeiro. This was key because Rio was a starting point for measuring distances. The Beagle carried 22 accurate marine chronometers. These clocks helped determine longitude. The ship had to stop at certain places to check these clocks.

The main survey work would start south of the Río de la Plata. The ship would return to Montevideo for supplies. They also needed to map Tierra del Fuego and the Falkland Islands. After that, they would map the west coast as far north as possible. The captain could then decide to survey the Galápagos Islands. Finally, the Beagle would go to Tahiti and Port Jackson, Australia. These known places would help check the chronometers.

The instructions also said not to waste time on fancy drawings. Maps should have simple notes and views of the land from the sea. They also needed to record tides and weather. An extra idea was to study a circular coral atoll in the Pacific Ocean. This would help understand how these coral reefs formed.

Getting Ready for the Journey

The previous trip to South America involved HMS Adventure and HMS Beagle. During that trip, the Beagle's captain, Pringle Stokes, died. Command was given to the young Robert FitzRoy. During that first trip, some native people from Tierra del Fuego took a ship's boat. FitzRoy tried to take some natives hostage. When that failed, he got four natives to come on board in exchange for buttons. He brought them back to England to be educated. One of them died from smallpox.

FitzRoy, then 27, hoped to lead a second trip to continue the mapping. When he heard the Navy might not support it, he worried about returning the Fuegians. He planned to take them back on a small merchant ship. But a kind uncle heard about this and contacted the Admiralty. Soon, FitzRoy was made commander of the Beagle for the new voyage. This happened on June 27, 1831.

Captain Francis Beaufort, who was in charge of mapping for the Admiralty, helped plan the long voyage. The Beagle was officially ready on July 4, 1831. FitzRoy spent a lot of money to refit the ship. The ship was known for being unstable and sinking easily. FitzRoy had the upper deck raised to make it safer and handle better. This also helped water drain faster. Extra wood on the hull made the ship heavier and more stable.

The ship was also one of the first to test lightning rods. FitzRoy also got five special barometers that did not use mercury. These gave accurate readings, which the Admiralty required.

Besides the officers and crew, the Beagle carried several extra people. FitzRoy hired a person to care for his 22 marine chronometers. He also hired an artist, Augustus Earle. The three Fuegians from the previous voyage were also returning home. A missionary named Richard Matthews was going with them.

Finding a Naturalist

Beaufort and other important scientists at Cambridge wanted a naturalist to join the expedition. They believed that scientific research should be done by gentlemen, not for money. The ship's doctor often collected specimens on voyages. The Beagle's doctor, Robert McCormick, wanted to be a famous naturalist. Collections made by officers usually belonged to the government and went to places like the British Museum. However, for this second voyage, officers could keep their own specimens.

FitzRoy had regretted on the first voyage that no one understood geology. He wanted someone who could study the land while he focused on mapping the sea. This meant he needed a naturalist who knew geology and could spend time ashore. McCormick, the ship's doctor, was not an expert in geology and had to stay on the ship for his duties.

FitzRoy knew that leading a ship could be stressful and lonely. He might have wanted a gentleman companion who shared his scientific interests. Professor John Stevens Henslow described the position as "more as a companion than a mere collector." This meant FitzRoy would treat his guest as an equal. Other ships at that time also carried unpaid civilian naturalists.

In August, FitzRoy talked to Beaufort about this position. Beaufort asked a Cambridge professor, George Peacock, to find a suitable person. Peacock suggested Reverend Leonard Jenyns. Jenyns almost accepted but worried about his church duties and health. He declined the offer. Henslow briefly thought of going, but his wife was unhappy about it. Both Jenyns and Henslow then suggested 22-year-old Charles Darwin. Darwin was on a geology trip and had just finished his degree. He planned to become a parson.

Darwin Gets the Offer

Darwin was a good fit for a gentleman naturalist. He was well-trained in natural history. He had developed a strong interest in geology during a field trip. On August 24, Henslow wrote to Darwin: "I think you are the best person I know for this job. Not because you are a perfect naturalist, but because you are good at collecting, observing, and noting things in natural history. Captain FitzRoy wants a companion, not just a collector. He will only take someone recommended as a gentleman. The trip will last two years. If you bring many books, you can do anything you like. This is a great chance for someone with enthusiasm. Don't doubt yourself; I truly think you are the right person."

The letter first went to George Peacock, who quickly sent it to Darwin. Peacock confirmed that the ship would sail around the end of September. When Darwin returned home on August 29, his father strongly objected to the voyage. The next day, Darwin wrote to decline the offer. But with his uncle's help, Darwin's father changed his mind and agreed to pay for the trip. On September 1, Darwin wrote to Beaufort accepting the offer. Beaufort then told FitzRoy that he had found a "Savant" (a learned person) for him. This was Mr. Darwin, "full of zeal and enterprise."

On Sunday, September 4, FitzRoy wrote back, strongly against Darwin joining. Both Darwin and Henslow gave up the idea. But Darwin went to London anyway. The next morning, he met FitzRoy. FitzRoy explained that his first choice for the position had just turned it down. FitzRoy warned Darwin about the difficulties, like cramped spaces and simple food. Darwin would pay about £30 a year for food. The total cost might be £500. The ship would sail on October 10 and be away for three years. They talked and dined together and found they liked each other. FitzRoy, a conservative, had been careful about having an unknown young man from a liberal background join him. He later joked that he almost rejected Darwin because the shape of his nose suggested a lack of determination.

Darwin Prepares for the Trip

While getting to know FitzRoy, Darwin quickly arranged his supplies. He got advice on how to preserve specimens from experts. He bought two pistols and a rifle for £50. FitzRoy had spent £400 on firearms. On September 11, FitzRoy and Darwin traveled to Portsmouth. Darwin was not seasick. He saw the "very small" ship and met the officers. He was happy to get a large cabin, which he shared with another surveyor. Darwin then rushed back to London and his family in Shrewsbury. He returned to Devonport on October 24.

The geologist Charles Lyell asked FitzRoy to record observations on geological features. Before they left England, FitzRoy gave Darwin the first volume of Lyell's Principles of Geology. This book explained how Earth's features formed slowly over very long periods. Darwin later remembered that Henslow had advised him to read the book but not to accept its ideas.

Darwin was an unpaid guest on the ship. He could leave the voyage whenever he wanted. He was most concerned about keeping control of his specimen collection. He even hesitated to be on the Admiralty's list for food until he was sure he could keep his specimens.

Beaufort first thought specimens should go to the British Museum. But Darwin knew that many specimens there were not studied. Beaufort assured him he could give them to other public groups, like the Zoological or Geological societies. Darwin decided new finds should go to the "largest & most central collection."

FitzRoy arranged for Darwin's specimens to be sent to England as official cargo. This meant Darwin did not have to pay for shipping. Henslow agreed to store them at Cambridge. Darwin's father would pay for land transport from the port.

Darwin's Work on the Expedition

The captain had to keep detailed records of his survey. Darwin also kept a daily log and detailed notes of his finds. He also kept a diary, which became his famous journal. Darwin's notes show he was very professional. He had learned how to take natural history notes while studying in Edinburgh. He had also collected beetles in Cambridge. But he was new to most other areas of natural history. During the voyage, Darwin studied small invertebrates. He collected other creatures for experts to study later in England. More than half of his zoology notes are about marine invertebrates. He also recorded his thoughts on why creatures behaved and lived where they did. He used the ship's excellent library but always questioned what he read.

Geology was Darwin's main interest on the trip. His geology notes were almost four times larger than his zoology notes. He wrote to his sister that "there is nothing like geology." He said finding a group of fossil bones was more exciting than hunting. For him, geology involved deep thinking and allowed him to develop theories.

The Voyage Begins

Charles Darwin had been told the Beagle would sail by the end of September 1831. But getting the ship ready took longer. The ship was finally ready on November 23. Strong westerly winds caused more delays. They tried to leave on December 10 and 21 but had to turn back. Finally, on the morning of December 27, the Beagle left Plymouth Sound and began its journey.

Atlantic Islands Exploration

The Beagle passed Madeira without stopping, just to confirm its position. On January 6, it reached Tenerife in the Canary Islands. But they were not allowed to land because of cholera in England. Darwin was very disappointed. With better weather, they sailed on. On January 10, Darwin used a special net he made to collect tiny sea creatures. He noted how beautiful these small animals were, even though they seemed to have "little purpose."

Six days later, they landed for the first time at Praia on Santiago Island in the Cape Verde Islands. This is where Darwin's published journal begins. At first, he thought the island was barren. But when he visited a deep valley, he saw the "glory of tropical vegetation." He had a "glorious day," amazed by the new sights and sounds. FitzRoy set up tents to measure the island's exact position. Darwin collected many sea animals and studied the island's geology.

Darwin saw a white layer of rock made from crushed coral and seashells. This layer was between black volcanic rocks. He noted a similar white layer in the cliffs 40 feet above sea level. The seashells looked like those found today. He thought that lava had covered this shell sand on the seabed. Then, the land had slowly risen. This supported Charles Lyell's idea that Earth's crust slowly rises and falls. Darwin was inspired to write a geology book.

The ship's doctor, Robert McCormick, wanted to be famous. He walked with Darwin in the countryside. Darwin found McCormick's ideas old-fashioned. They saw a huge baobab tree. Darwin went on other trips with other officers. FitzRoy extended their stay to 23 days to finish his measurements. Darwin wrote that he found an octopus that could change its colors like a chameleon.

McCormick became annoyed that FitzRoy favored Darwin. On February 16, FitzRoy landed a small group, including Darwin, on Saint Peter and Paul Rocks. They found seabirds so tame they could be easily caught. McCormick was left circling the islets in another boat. That evening, new sailors crossed the equator in a traditional ceremony.

Darwin had a special position as a guest and equal to the captain. Junior officers called him "sir." The captain later nicknamed Darwin Philos, meaning "ship's philosopher."

Mapping South America

In South America, the Beagle carefully mapped the coasts. Darwin took long trips inland with local guides. He spent much time away from the ship. He would meet the ship at ports where mail arrived. His notes, journals, and collections were sent back to England. He made sure his collections were his own. Batches of his specimens were shipped to England and then sent to Henslow in Cambridge.

Other people on board, including FitzRoy and other officers, were also amateur naturalists. They helped Darwin and collected specimens for the Crown. These went to the British Museum.

Tropical Beauty and Human Rights

Due to strong waves, they stayed only one day at Fernando de Noronha. Then FitzRoy sailed to Bahia, Brazil, to check the clocks and get water. They reached the port on February 28. Darwin was thrilled by the beautiful city of Bahia. The next day, he was overjoyed walking alone in the tropical forest. He continued to take "long naturalizing walks" with others.

He found the sight of slavery upsetting. When FitzRoy defended it, Darwin disagreed. FitzRoy became angry and banned Darwin from his company. But within hours, FitzRoy apologized and asked Darwin to stay. Later, FitzRoy heard a British captain tell "revolting facts" about slavery. This made FitzRoy silent. The ship finished mapping the harbor on March 18. Then it sailed down the coast to map the Abrolhos reefs.

They sailed the Beagle into Rio de Janeiro harbor on April 4. Darwin was excited to open letters from home. He was surprised to hear that his friend Fanny Owen was getting married. The artist Augustus Earle showed Darwin around town. They found a nice cottage to stay in. Darwin went on a difficult riding trip to Rio Macaè with local landowners.

Robert McCormick, the ship's doctor, had made FitzRoy and the first lieutenant unhappy. So he was sent home. Assistant Surgeon Benjamin Bynoe took his place.

The measurements at Rio showed a small error compared to earlier maps. FitzRoy wrote to Beaufort that he would go back to check.

On April 24, Darwin returned to the ship. His books and equipment were slightly damaged when his boat was swamped. He sent his journal to his sister, asking for comments. He decided to stay in the cottage with Earle while the ship went to Bahia.

Eight crew members had gone hunting near Rio. After they returned on May 2, some got sick with a fever. The ship sailed on May 10. A sailor, a ship's boy, and a young midshipman died. The ship returned to Rio on June 3. FitzRoy confirmed his measurements were correct.

At the cottage, Darwin wrote his first letter to Henslow about his collecting. He said he would not send a box until they reached Montevideo. He returned to the ship on June 26. They set sail on July 5.

The Beagle also had a diplomatic role. When they arrived at Montevideo on July 26, another British ship signaled them to prepare for battle. British property had been seized during unrest. They took measurements for the chronometers. On July 31, they sailed to Buenos Aires to meet the governor. But a guard ship fired warning shots. FitzRoy complained and left, threatening to fire back. When they returned on August 4, FitzRoy told the other captain, who went to demand an apology. On August 5, local officials asked FitzRoy for help to stop a mutiny. Darwin and 50 armed men from the ship went to the fort. Darwin enjoyed the excitement. He wrote, "It was something new to me to walk with Pistols & Cutlass through the streets of a Town." The other British ship returned on August 15 with an apology.

Darwin's first box of specimens was ready. It was sent on August 19. Henslow received it in mid-January. On August 22, the Beagle began mapping the coast south of Cape San Antonio.

Amazing Fossil Discoveries

At Bahía Blanca, Darwin rode inland with gauchos. He saw them use bolas to catch rheas (large birds like ostriches). He also ate roasted armadillo. On September 22, he went on a pleasant trip around the bay with FitzRoy. They stopped at Punta Alta. In low cliffs there, Darwin found rocks with many shells and fossil teeth and bones of huge extinct mammals. These were in layers near a dirt layer with shells and armadillo fossils. This suggested to him that they were from quiet tidal deposits, not a sudden disaster. With help, Darwin collected many fossils over several days. Others found his "cargoes of apparent rubbish" amusing.

He spent much of the second day digging out a large skull. It seemed to be related to a rhinoceros. On October 8, he returned and found a jawbone and tooth. He identified them as Megatherium fossils, or perhaps Megalonyx. He was excited because the only other specimens in Europe were in a king's collection in Madrid. In the same layer, he found large bony plates. He first thought they were from a giant armadillo. But he later thought they were from a Megatherium. With FitzRoy, Darwin went about 30 miles across the bay to Monte Hermoso on October 19. There, he found many fossils of smaller rodents, unlike the huge mammals from Punta Alta.

They returned to Montevideo. On November 2, they revisited Buenos Aires. The guard ship now treated them with respect. Darwin learned that the Megatherium fossil reported in the newspaper came from the same rock layers as his own finds. He also bought "fragments of some enormous bones." In Montevideo, from November 14, he packed all his specimens, including the fossils. He sent them on a ship to Falmouth.

The mail from home included the second volume of Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology. This book argued against Lamarckism, which suggested species changed over time. Lyell believed species appeared mysteriously and were perfectly suited to their "centers of creation." They then died out if the environment changed.

Exploring Tierra del Fuego

They reached Tierra del Fuego on December 18, 1832. Darwin was surprised by the native Yaghan people. He found them very different from the "civilized" Fuegians they were returning. He described his first meeting with the natives as "the most curious and interesting spectacle I ever beheld." He said the difference between "savage and civilised man" was greater than between wild and domesticated animals. He felt the natives looked like "Devils on the Stage." In contrast, he said of Jemmy Button, one of the educated Fuegians, that it was "wonderful" how many good qualities he had. (Years later, Darwin used these thoughts to support his idea that humans had developed from simpler forms.)

On January 23, 1833, they set up a mission post on "Buttons Land." They built huts and gardens. Nine days later, they returned to find the possessions looted and shared by the natives. The missionary, Matthews, gave up and rejoined the ship. The three educated Fuegians stayed to continue the mission work. The Beagle then went to the Falkland Islands. Darwin studied how species related to their habitats. He found old fossils similar to those in Wales. FitzRoy bought a smaller ship to help with mapping. Darwin hired a servant, Syms Covington, to help him collect specimens.

Gauchos, Rheas, and More Fossils

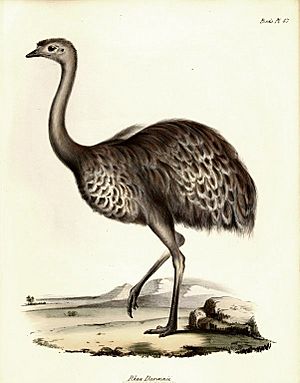

The two ships sailed to the Río Negro in Argentina. On August 8, 1833, Darwin went on another trip inland with the gauchos. On August 12, he met General Juan Manuel de Rosas, who was leading a military campaign. Darwin got a passport from him. As they crossed the pampas, the gauchos told Darwin about a rare, smaller species of rhea. After three days, he revisited Punta Alta. He looked at the geology with his new knowledge. He wondered if the bones were older than the seashells. He found many bones. On September 1, he found a nearly complete skeleton with bones still in place.

He set off again. On October 1, he found a huge tooth in the cliffs of the Carcarañá River. Then, in a cliff of the Paraná River, he saw "two great groups of immense bones." They were too soft to collect, but a tooth fragment showed they were mastodons. Illness delayed him. He was puzzled to find a horse tooth in the same rock layer as a huge armadillo fossil. Horses had been brought to the continent by Europeans. They took a riverboat to Buenos Aires but got caught in a revolution. With his passport, Darwin escaped with refugees. They rejoined the Beagle at Montevideo.

Since surveys were still ongoing, Darwin went on another 400-mile trip in Banda Oriental. He visited a ranch near Mercedes. On November 25, he heard about "giant bones," which were Megatherium. He could only get a few broken pieces. The next day, he bought a Megatherium head for about two shillings. Its teeth were broken, and the lower jaw was missing. He arranged to ship the skull to Buenos Aires. He also saw a club-like tail, which he sketched. His notes showed he realized the land had risen and fallen.

Back in Montevideo, Darwin met Conrad Martens, the new artist on the Beagle. They sailed south. On December 24, Darwin shot a guanaco for their Christmas meal. In the new year, Martens shot a rhea. Darwin realized it was the rare smaller rhea and saved its remains. On January 9, 1834, they reached Port St Julian. Darwin found fossils of a large animal. On January 26, they entered the Straits of Magellan. They met tall Patagonian natives. One told him that the smaller rheas lived only in the south, while the larger ones lived in the north.

After more mapping in Tierra del Fuego, they returned on March 5, 1834, to visit the missionaries. The huts were empty. Then canoes approached, and they saw Jemmy Button. He had lost his possessions and returned to native ways, taking a wife. Darwin had never seen "so complete & grievous a change." Jemmy came on board, ate with cutlery, and spoke English well. He said he did not want to return to England. He gave them gifts and returned to his wife. Darwin had once thought these natives were "miserable, degraded savages." But Jemmy had adapted to civilization and then chosen to return to his old life. This raised questions for Darwin about human development.

Around this time, Darwin wrote an essay called Reflection on Reading My Geological Notes. He thought about why the land kept rising. He also considered the history of life in Patagonia.

They returned to the Falkland Islands on March 16. Darwin learned that his first fossil shipment had reached Cambridge. Experts were very impressed, especially by the Megatherium fossils. This made Darwin famous.

The Beagle then sailed to southern Patagonia. On April 19, an expedition went up the Santa Cruz river. They dragged boats upstream. The river cut through hills and plains covered with shells. Darwin discussed with FitzRoy that these terraces were old shores that had slowly risen. They saw some smaller rheas but could not catch them. The expedition got close to the Andes but had to turn back.

Darwin wrote about his ideas in his essay on the Elevation of Patagonia. He suggested that the plains had risen in stages over a large area. He supported Lyell's idea that normal processes, not sudden floods, caused these changes. Shells found far inland still had their color. This suggested the process was recent and could have affected human history.

West Coast of South America

The Beagle and Adventure mapped the Straits of Magellan. Then they sailed north up the west coast. They reached Chiloé Island on June 28, 1834. They spent the next six months mapping the coast and islands. On Chiloé, Darwin found pieces of coal and petrified wood.

They arrived at Valparaíso on July 23. Darwin wanted to find some fossil bones. On August 14, he rode into the Andes mountains. Three days later, they spent a day on the top of "The Bell Mountain," Cerro La Campana. Darwin visited a copper mine. He spent five days climbing in the mountains before going to Santiago, Chile. On his way back, he got sick on September 20 and had to stay in bed for a month. He might have caught Chagas' disease here, which some believe caused his later health problems. He learned that the Admiralty had criticized FitzRoy for buying the Adventure. FitzRoy had taken it badly and sold the ship. He even resigned his command, doubting his sanity. But his officers convinced him to stay. The artist Conrad Martens left the ship and went to Australia.

After waiting for Darwin, the Beagle sailed on November 11 to map the Chonos Archipelago. From there, they saw the Osorno volcano erupting. Darwin wondered about the fossils he had found. The giant Mastodons and Megatheriums were extinct. But he found no signs of a sudden flood. He agreed with Lyell's idea of species slowly appearing and disappearing. But Darwin was willing to believe that extinct species had simply "aged and died out."

They arrived at Valdivia on February 8, 1835. Twelve days later, Darwin was on shore when a strong earthquake hit. He returned to find the town badly damaged. They sailed 200 miles north to Concepción. On March 4, they found the city destroyed by the same earthquake and a tsunami. Even the cathedral was in ruins. Darwin noted the destruction. FitzRoy found that mussel beds were now above high tide. This showed the ground had risen about 9 feet. They had seen the continent slowly rising from the ocean, just as Lyell had described.

They returned to Valparaiso on March 11. Darwin started another trek up the Andes three days later. On March 21, he reached the continental divide at 13,000 feet. Even here, he found fossil seashells in the rocks. He felt the view was like "watching a thunderstorm." After going to Mendoza, they returned by a different pass. They found a petrified forest of fossilized trees. This showed him that the trees had been on a Pacific beach. The land had sunk, burying them in sand. The sand became rock, and then the land slowly rose to 7,000 feet in the mountains. On returning to Valparaiso, he wrote to his family that his findings, if accepted, would be very important for understanding how the world formed. After another hard trip in the Andes, he rejoined the Beagle at Copiapó on July 5. They sailed to Lima. But there was a rebellion, so he had to stay on the ship. Here, he realized that Lyell's idea about coral atolls might be wrong. He thought it made more sense if volcanoes slowly sank, and the coral reefs kept building up to sea level, forming an atoll as the volcano disappeared. He planned to check this theory when they reached such islands.

On June 14, FitzRoy heard that his friend's ship, HMS Challenger, had shipwrecked. FitzRoy helped rescue the survivors. Wickham took the Beagle to Copiapó. Darwin rejoined the ship on July 5, and they continued to Lima. On September 9, FitzRoy joined them in Lima.

Galápagos Islands Discoveries

A week after leaving Lima, the Beagle reached the Galápagos Islands on September 15, 1835. The next day, Captain FitzRoy anchored near Chatham Island. Darwin spent his first hour on the islands at a place now called Frigatebird Hill.

Darwin was excited to see newly formed volcanic islands. He went ashore whenever he could while the Beagle mapped the coast. He found black volcanic rock under the hot sun. He made detailed notes on volcanic cones that looked like chimneys. He was disappointed not to see active volcanoes or signs of uplift. But an officer found broken oyster shells high above the sea. Huge Galápagos tortoises seemed very old. Large black marine iguanas looked "disgusting" but were well suited to their home. Darwin had learned to study how species were spread out. He tried to collect flowering plants. He found only ten species of thin, "wretched-looking" scrub. There were very few insects. Birds were not afraid of humans. He noted that a mockingbird was similar to those he had seen on the mainland.

The Beagle sailed to Charles Island. They met Nicholas Lawson, the acting Governor of Galápagos. He told them that tortoises differed in shell shape from island to island. He said he could tell which island a tortoise came from just by looking at it. Darwin remembered this later. He found a mockingbird and noticed it was different from the one on Chatham Island. From then on, he carefully noted where mockingbirds were caught. He collected many animals, plants, insects, and reptiles. He wondered where these creatures came from. At this point, he still believed species did not change.

They went to Albemarle Island. Darwin saw smoke from a volcano. On October 1, he landed near Tagus Cove. He saw his first Galapagos land iguanas. Water pits were poor for drinking but attracted many small birds. Darwin made his only note about the finches here. He caught a third species of mockingbird.

After passing other northern islands, Darwin was left on James Island for nine days with the surgeon and their servants. They collected many specimens while the Beagle went back for fresh water.

After more mapping, the Beagle sailed for Tahiti on October 20, 1835. Darwin wrote his notes. To his surprise, he found that all the mockingbirds from Charles, Albemarle, James, and Chatham Islands were different. He wrote that these birds were "singular from existing as varieties or distinct species in the different Isds." He noted that each variety stayed on its own island. He wondered if this meant that species were not fixed. This idea later led him to believe in transmutation of species, or evolution.

From Tahiti to Home

They sailed on, eating Galapagos tortoises. They passed the atoll of Honden Island on November 9. Darwin found the low islands "uninteresting." Arriving at Tahiti on November 15, he was interested in the lush plants and friendly natives. He saw how Christianity had helped them.

On December 19, they reached New Zealand. Darwin thought the tattooed Māori were savages, of a "much lower order" than the Tahitians. He also found them and their homes "filthily dirty." Darwin saw missionaries improving their character and teaching new farming methods. Richard Matthews, the missionary, stayed here. Darwin and FitzRoy agreed that missionaries had been unfairly criticized. Darwin also noted many bad English residents, including escaped convicts. By December 30, he was glad to leave New Zealand.

The first sight of Australia on January 12, 1836, reminded him of Patagonia. But inland, the country was better. He admired the busy city of Sydney. On a trip inland, he met some Aboriginal peoples. He thought they looked "good-humoured & pleasant" and not as "degraded" as often said. They threw spears for a shilling. He sadly thought about how their numbers were quickly decreasing. At a sheep farm, he caught his first marsupial, a "potoroo" (rat-kangaroo). He thought about Australia's strange animals. He wondered if two different Creators had been at work. Yet, an antlion he watched was very similar to its European cousin. That evening, he saw the even stranger platypus. He noticed its bill was soft, unlike preserved specimens. Few Europeans believed Aboriginal stories that platypuses laid eggs.

The Beagle visited Hobart, Tasmania. Darwin was impressed by the settlers' society. But he noted that the island's "Aboriginal blacks are all removed & kept (in reality as prisoners) in a Promontory." He believed this "cruel step" was necessary because of the "misconduct of the Whites." They then sailed to King George's Sound in south-west Australia. Darwin was impressed by the "good disposition of the aboriginal blacks." He gave boiled rice to an Aboriginal dancing party. He found it a "most rude barbarous scene" but everyone seemed happy. The Beagle's departure was delayed when it ran aground in a storm. It was refloated and continued its journey.

Keeling Island and the Journey Home

FitzRoy's orders from the Admiralty included studying a circular coral atoll. This was to learn how coral reefs formed. He chose the Keeling Islands in the Indian Ocean. On arrival on April 1, the whole crew started work. Darwin found a coconut-based economy. There were few native plants or land birds, but many hermit crabs. The lagoons were full of sea creatures and fish. He studied the atoll's structure based on his theory from Lima. This theory suggested that encircling reefs become atolls as an island sinks. FitzRoy's measurements supported this idea.

Arriving at Mauritius on April 29, 1836, Darwin was impressed by the French colony. He toured the island, looking at its volcanic mountains and coral reefs. The Surveyor-general took him on the island's only elephant to see an elevated coral plain. FitzRoy was writing the official story of the Beagle voyages. After reading Darwin's diary, he suggested they publish it together.

The Beagle reached the Cape of Good Hope on May 31. In Cape Town, Darwin received a letter from his sister. It mentioned "the little books, with the Extracts from your Letters." Darwin was horrified that his casual words were in print. But he realized it could not be helped. Unknown to Darwin, his fame was growing. Parts of his letters had been read to scientific societies in London and Cambridge. His father was very pleased with "your book."

Darwin explored the geology of the area. He formed ideas about rock formations that differed from Lyell's. The zoologist Andrew Smith showed him rock formations. They discussed how large animals could live on sparse plants. This showed that a lack of lush plants did not explain why giant creatures in South America died out.

Around June 15, Darwin and FitzRoy visited the famous astronomer Sir John Herschel. Darwin called this "the most memorable event." His interest in science had been sparked by Herschel's book. Their discussion is not recorded. But Herschel had praised Lyell's geology book. He believed it would lead to new ideas about how extinct species were replaced by new ones. Herschel thought that new species appearing was a natural process, not a miracle.

In Cape Town, missionaries were accused of causing racial tension. After the Beagle sailed on June 18, FitzRoy wrote an open letter. He used parts of his and Darwin's diaries to defend the missionaries. This was FitzRoy's (and Darwin's) first published work.

On July 8, they stopped at St. Helena for six days. Darwin explored the island. He noted its complex rock layers and volcanic features. He also saw that native plants had been replaced by imported species.

At this stage, Darwin was very interested in how animals and plants were spread on islands. He described St. Helena as "a little centre of creation." He later remembered doubting that species were permanent. When organizing his bird notes, Darwin wrote about the Galapagos mockingbirds. He noted that different kinds were found on different islands. He wrote, "If there is the slightest foundation for these remarks the zoology of Archipelagoes – will be well worth examining; for such facts [would] undermine the stability of Species." This was the first time he wrote about his doubts about species being fixed. This led him to believe in evolution.

The Beagle reached Ascension Island on July 19, 1836. Darwin was happy to get letters from his sisters. They told him that a professor had written that Darwin was "doing admirably" and would have "a great name among the Naturalists of Europe." Darwin later remembered climbing the mountains with his "geological hammer." He agreed that Ascension Island was like a "cinder" compared to St. Helena. He noted the effort to grow plants there.

On July 23, they set off, eager to go home. But FitzRoy wanted to check his longitude measurements. So he took the ship back across the Atlantic to Bahia in Brazil. Darwin was glad to see the jungle one last time. But he now compared the "stately Mango trees with the Horse Chesnuts of England." The trip was delayed when the Beagle had to shelter at Pernambuco. Darwin studied rocks and marine animals there. The Beagle finally departed for home on August 17. After a stormy journey, the Beagle reached England on October 2, 1836, anchoring at Falmouth, Cornwall.

The Return Home

On the stormy night of October 2, 1836, Darwin immediately left Falmouth by mail coach. He traveled for two days to his family home in Shrewsbury, Shropshire. He wrote to FitzRoy that the English countryside was "beautiful & cheerful." He now knew that "the wide world does not contain so happy a prospect as the rich cultivated land of England." He arrived late on October 4. The next morning, he greeted his family. His sisters said he looked the same. But his father said, "Why, the shape of his head is quite altered." After spending time with family, Darwin went to Cambridge on October 15. He asked Henslow for advice on organizing his collections.

Darwin's father gave him money so he did not need to work. Darwin was now a scientific celebrity. His fossils and letters had made him famous. He visited scientific groups in London. He was now part of the "scientific establishment." He worked with experts to describe his specimens. Charles Lyell supported him strongly. In December 1836, Darwin gave a talk in Cambridge. On January 4, 1837, he read a paper to the Geological Society of London. It proved that Chile and South America were slowly rising.

Darwin was willing to have his diary published with FitzRoy's account. But his relatives urged him to publish it separately. On December 30, it was decided that Darwin's journal would be the third volume of the Narrative. Darwin started reorganizing his diary. He added scientific material from his notes. He finished his Journal and Remarks (now known as The Voyage of the Beagle) in August 1837. But FitzRoy was slower. The three volumes were published in August 1839.

Syms Covington stayed with Darwin as his servant. On February 25, 1839, Covington left on good terms and moved to Australia.

Expert Studies of Darwin's Collections

Darwin had been a great collector. He did his best with the books he had on the ship. Now, expert specialists would study his specimens. They would decide which ones were new and give them scientific names.

Fossil Discoveries

Richard Owen was an expert in comparing animal body parts. His studies showed a series of similar species in the same place. This gave Darwin important ideas for his new views. Owen met Darwin on October 29, 1836. He quickly started describing the new fossils. At that time, only a few fossil mammals from South America had been fully described. On November 9, Darwin wrote that some of his fossils were "great treasures." The nearly complete skeleton from Punta Alta was like a giant anteater, the size of a small horse. The rhinoceros-sized head bought near Mercedes was not a megatherium. It was a "gnawing animal." Darwin joked, "What famous Cats they ought to have had in those days!"

Over the next few years, Owen published descriptions of the most important fossils. He named several new species. He described the fossils from Punta Alta. These included a nearly perfect head of Megatherium Cuvierii. He also found the jaw of a related species, which Owen named Mylodon Darwinii. And jaws of Megalonyx Jeffersonii. The nearly complete skeleton was named Scelidotherium by Owen. He found that most of its bones were still in their correct places. At the nearby Monte Hermoso beds, many rodents were found. These included species related to the Brazilian tuco-tuco and the capybara.

Owen decided that the fossils of bony plates found in several places were not from the Megatherium. They were from a huge armadillo, as Darwin had first thought. Owen named this fossil Glyptodon clavipes in 1839. Darwin's find from Punta Alta, a large folded piece of armor with toe bones inside, was identified as a slightly smaller Glyptodont named Hoplophorus.

The huge skull from near Mercedes was named Toxodon by Owen. He showed that the "enormous gnawing tooth" from the cliffs of the Carcarañá River was a molar from this species. The finds near Mercedes also included a large piece of Glyptodont armor. Owen also found parts of another Toxodon jaw and tooth in the Punta Alta fossils.

The fossils from near Santa Fe included a horse tooth. This had puzzled Darwin because horses were thought to have arrived in the Americas only in the 16th century. It was found near a Toxodon tooth and a Mastodon tooth. Owen confirmed that the horse tooth was from an extinct South American species. He named it Equus curvidens. This discovery was later explained as part of the evolution of the horse.

The "soft as cheese" Mastodon bones at the Paraná River were identified as two huge skeletons of Mastodon andium. Mastodon teeth were also found from Santa Fe and the Carcarañá River. The pieces of spine and a hind leg from Port S. Julian puzzled Owen. He named the creature Macrauchenia. It seemed to be a "gigantic and most extraordinary pachyderm" (a thick-skinned mammal), related to the Palaeotherium, but also similar to the llama and the camel.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |