Darwin's finches facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Darwin's finches |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Large ground finch, Medium ground finch Small tree finch, Green warbler-finch |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genera | |

|

Geospiza |

|

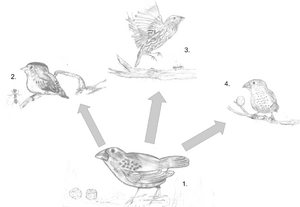

Darwin's finches, also called the Galápagos finches, are a group of about 18 different species of small passerine birds. They are famous for their amazing variety in beak shapes and how they use them. These birds are part of the tanager family. They are not closely related to the true finches you might know.

The closest known relative of the Galápagos finches is the Tiaris obscurus from South America. Charles Darwin first collected these birds on the Galápagos Islands during his second trip on the ship HMS Beagle. Most of these finches live only on the Galápagos Islands. However, one species, the Cocos finch, lives on Cocos Island.

The name "Darwin's finches" was first used by Percy Lowe in 1936. It became very popular after David Lack wrote his book Darwin's Finches in 1947. These birds range in size from 10 to 20 centimeters (about 4 to 8 inches). They weigh between 8 and 38 grams (less than an ounce to about 1.3 ounces). The smallest are the warbler-finches, and the largest is the vegetarian finch. The biggest differences between the species are the size and shape of their beaks. Their beaks are perfectly adapted to help them eat different kinds of food. All the birds have dull colors.

How Darwin Studied Finches

During his journey on HMS Beagle, Darwin didn't realize how important the Galápagos birds were. He was learning about geology at the time. He mostly let his servant, Syms Covington, collect bird specimens. Even so, these birds later played a huge role in Darwin's ideas about evolution through natural selection.

When Darwin was on the Galápagos Islands, he thought about how species were created in specific places. He was interested in how species on islands were connected to those on nearby continents. On Chatham Island, he saw a mockingbird that looked like ones he had seen in Chile. Later, he found a different mockingbird on Charles Island. He carefully noted where each mockingbird was caught.

However, he didn't pay much attention to the finches at first. As he sailed home, he realized that the mockingbirds from different islands were actually different species. This, along with what he learned about Galápagos tortoises, made him wonder if species could change over time.

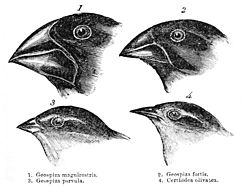

- Geospiza magnirostris

- Geospiza parvula

- Certhidea olivacea

- Geospiza fortis

After his trip, Darwin gave the finches he collected to the Zoological Society of London in January 1837. The bird specimens were given to John Gould, a famous English ornithologist. Gould identified the birds. He reported that the birds Darwin thought were blackbirds, "gross-beaks", and finches were actually "an entirely new group" of 12 species of ground finches. This news was even in the newspapers!

Darwin met Gould again in March. He learned that his Galápagos "wren" was another type of finch. He also found out that the mockingbirds he had labeled by island were separate species, not just different types of the same species. Gould found more species than Darwin expected. He concluded that 25 out of 26 land birds were new and unique to the Galápagos. However, they were closely related to birds found on the South American continent.

Darwin then realized that if finch species were found only on certain islands, like the mockingbirds, it would explain why there were so many species on the islands. He asked others on the expedition for information. Captain Robert FitzRoy, FitzRoy's steward Harry Fuller, and Darwin's servant Covington had also collected specimens and labeled them by island. Using this information, Darwin tried to figure out where he had collected his own specimens. These findings helped support his idea that species could change over time.

Darwin's Writings on Finches

When Darwin wrote his travel diary, The Voyage of the Beagle, he included Gould's findings. He noted that even though the species were unique to the islands, they were very similar to American birds in their structure, habits, color, and even voice.

In the first edition of The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin wrote about the finches' beaks. He said it was amazing to see how the beaks changed gradually within this one group of birds. Some beaks were as big as a large grosbeak's, while others were as small as a warbler's.

By the time the first edition was published, Darwin was already working on his theory of natural selection. For the second edition of The Voyage in 1845, he added more details about the birds' beaks. He also added two sentences that showed his new ideas:

Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends."

Darwin also discussed the finches in his famous book, On the Origin of Species. He explained how island animals are often related to those on the nearest mainland, but are not exactly the same species. He used the Galápagos Archipelago as an example:

The most striking and important fact for us in regard to the inhabitants of islands, is their affinity to those of the nearest mainland, without being actually the same species. [In] the Galapagos Archipelago ... almost every product of the land and water bears the unmistakable stamp of the American continent. There are twenty-six land birds, and twenty-five of these are ranked by Mr. Gould as distinct species, supposed to have been created here; yet the close affinity of most of these birds to American species in every character, in their habits, gestures, and tones of voice, was manifest. ... The naturalist, looking at the inhabitants of these volcanic islands in the Pacific, distant several hundred miles from the continent, yet feels that he is standing on American land. Why should this be so? Why should the species which are supposed to have been created in the Galapagos Archipelago, and nowhere else, bear so plain a stamp of affinity to those created in America? There is nothing in the conditions of life, in the geological nature of the islands, in their height or climate, or in the proportions in which the several classes are associated together, which resembles closely the conditions of the South American coast: In fact there is a considerable dissimilarity in all these respects. On the other hand, there is a considerable degree of resemblance in the volcanic nature of the soil, in climate, height, and size of the islands, between the Galapagos and Cape de Verde Archipelagos: But what an entire and absolute difference in their inhabitants! The inhabitants of the Cape de Verde Islands are related to those of Africa, like those of the Galapagos to America. I believe this grand fact can receive no sort of explanation on the ordinary view of independent creation; whereas on the view here maintained, it is obvious that the Galapagos Islands would be likely to receive colonists, whether by occasional means of transport or by formerly continuous land, from America; and the Cape de Verde Islands from Africa; and that such colonists would be liable to modification — the principle of inheritance still betraying their original birthplace.

See also

In Spanish: Pinzón de Darwin para niños

In Spanish: Pinzón de Darwin para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |