Prester John facts for kids

Prester John (which means "Priest John") was a legendary Christian king and priest. Stories about him were very popular in Europe from the 1100s to the 1600s. People believed he ruled a powerful Christian nation far away in the East, surrounded by non-Christian lands. These tales were often filled with amazing stories and magical ideas. Prester John was sometimes said to be a descendant of the Three Magi (the Three Wise Men). His kingdom was thought to be full of riches, wonders, and strange creatures.

At first, people imagined Prester John lived in India. This idea came from stories about Nestorian Christians (a type of Christian group) spreading their faith there. Also, tales of Thomas the Apostle's travels in India helped start the legend. Later, after the Mongols came to Europe, people thought Prester John might be in Central Asia. Eventually, Portuguese explorers believed he was the ruler of Ethiopia in Africa. Ethiopia was a Christian kingdom that was far away from other Christian countries.

Contents

How the Legend Started

The exact beginning of the Prester John legend isn't clear. But it was strongly influenced by older stories about the East and travelers' tales. One important influence was the story of Saint Thomas the Apostle. He was said to have spread Christianity in India. This idea made Europeans think of India as a place of exotic wonders. It also gave the earliest idea of a Christian group being formed there. These ideas were very important in later stories about Prester John.

Stories about the Church of the East (also called Nestorianism) in Asia also helped shape the legend. This Christian church had many followers in Eastern nations. Europeans found it both mysterious and familiar. The church's success in converting people among the Mongols and Turks in Central Asia was especially inspiring. Some historians think the Prester John story might have come from the Keraites clan. Many of their members joined the Church of the East around the year 1000. By the 1100s, the Kerait rulers still used Christian names, which might have helped the legend grow.

The legend might also have been inspired by an early Christian figure named John the Presbyter from Syria. He was thought to be a teacher of important church leaders. The title "Prester" comes from the Greek word "presbuteros," which means "elder." It was used for important priests. This is where the English word "priest" comes from.

Later stories about Prester John often borrowed details from other books about the East. These included old travel books and made-up adventure tales. For example, parts of the story of Sinbad the Sailor were sometimes used. The Alexander Romance, a fantastic story about Alexander the Great's travels, was also very influential.

The Prester John legend really began in the early 1100s. Reports came from an archbishop of India visiting Constantinople and a patriarch of India visiting Rome. These visits, possibly from the Saint Thomas Christians of India, are hard to confirm. However, in 1145, a German writer named Otto of Freising wrote about meeting Hugh of Jabala, a bishop from Syria. Hugh told Otto that Prester John, a Nestorian Christian who was both a priest and a king, had won a great battle. He had taken the city of Ecbatana from its rulers. After this, Prester John supposedly planned to go to Jerusalem to help the Christians there. But the Tigris river was too flooded, so he had to go back home. Hugh also said Prester John was incredibly wealthy and had an emerald scepter. He was also holy because he was a descendant of the Three Magi.

Some historians connect this story to a real event in 1141. The Qara Khitai khanate, led by Yelü Dashi, defeated the Seljuk Turks in a battle near Samarkand. The Seljuks were a powerful Muslim group. This defeat weakened them a lot. The Qara Khitai were Buddhists, not Christians. But some of their allies were Nestorian Christians. Europeans, who didn't know much about Buddhism, might have thought that if a leader wasn't Muslim, he must be Christian. This victory gave hope to the Crusaders. It made them think a powerful Eastern king might help them.

The Letter of Prester John

The next big part of the story appeared around 1165. Copies of a letter, likely a fake, began to spread across Europe. This "Letter of Prester John" was a fantastic tale. It was supposedly written by Prester John himself to the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus. In the letter, Prester John claimed to be a descendant of one of the Three Magi and the King of India. The letter described many amazing riches and magical things in his kingdom. Europeans were fascinated by it, and it was translated into many languages, including Hebrew. It continued to spread for centuries, getting more detailed with each copy. When printing was invented, the letter became even more popular. It was still well-known during the Age of European Exploration. A key idea in the letter was that a lost kingdom of Nestorian Christians still existed in the vast lands of Central Asia.

People believed these reports so much that Pope Alexander III sent a letter to Prester John in 1177. He sent it with his doctor, Philip. We don't know what happened to Philip, but he likely didn't return with a message from Prester John. The "Letter" kept circulating and grew even more elaborate. Today, experts think the letter was probably written by someone in Western Europe, possibly in northern Italy or France.

The Mongol Empire and Prester John

In 1221, Jacques de Vitry, a bishop, returned from a failed Crusade. He brought exciting news: King David of India, said to be Prester John's son or grandson, had gathered his armies against the Muslims. He had already conquered Persia and was moving towards Baghdad. This king, whose ancestor had defeated the Seljuks in 1141, planned to take back Jerusalem. Some historians think this legend was revived to give Christians hope. It also aimed to convince European kings to join costly Crusades again. The bishop was right that a great king had conquered Persia. But "King David" turned out to be the Mongol ruler, Genghis Khan.

The rise of the Mongol Empire allowed Western Christians to visit lands they had never seen. Many travelers went along the empire's safe roads. The belief that a lost Nestorian kingdom existed in the East was one reason for this. Another was the hope of forming an alliance with an Eastern ruler to help the Crusader states. This led to many Christian ambassadors and missionaries being sent to the Mongols. These included explorers like Giovanni da Pian del Carpine in 1245 and William of Rubruck in 1253.

During this time, people started connecting Prester John with Genghis Khan. Prester John was identified with Toghrul, the king of the Keraites. Toghrul was Genghis Khan's foster father. Travelers like Marco Polo and William of Rubruck wrote about Prester John. They described him as a more realistic earthly king, not a magical hero. Marco Polo's book, Travels, says the war between Prester John and Genghis Khan began when Genghis Khan asked to marry Prester John's daughter. Prester John was angry that his lower-ranking vassal would ask this. He refused. In the war that followed, Genghis Khan won, and Prester John died.

The real person behind these stories was Toghrul. He was a Nestorian Christian ruler who was defeated by Genghis Khan. Toghrul had helped raise Genghis Khan after his father died. They were allies at first, but they had a disagreement. After Toghrul refused a marriage proposal between their children, war broke out in 1203. Genghis Khan captured Toghrul's brother's daughter, Sorghaghtani Beki. He married her to his son Tolui. They had several children, including Möngke and Kublai.

In this period, Prester John was often shown as just one of many enemies defeated by the Mongols. But as the Mongol Empire began to fall apart, Europeans stopped thinking Prester John was a Central Asian king. Travel in the region became dangerous without the empire's protection. So, in later books like The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Prester John's kingdom became fantastic again. It was placed back in India or another exotic location. Some stories even connected Prester John to the Holy Grail legend.

Prester John in Ethiopia

Prester John had been thought of as the ruler of India since the legend began. But "India" was a very general idea for Europeans in the Middle Ages. They often talked about "Three Indias." Since they didn't know much about the Indian Ocean, they sometimes thought Ethiopia was one of these "Indias." Europeans knew Ethiopia was a powerful Christian nation. But contact with it had been rare since the rise of Islam. Since Prester John couldn't be found in Asia, Europeans started to suggest that the legend referred to the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia. Evidence shows that people began to think Prester John's kingdom was in Ethiopia around 1250.

Marco Polo had described Ethiopia as a magnificent Christian land. But he didn't place Prester John there. Then, in 1306, 30 Ethiopian ambassadors came to Europe. In a record of their visit, Prester John was mentioned as the leader of their church. Another description of an African Prester John appeared around 1329. A missionary named Jordanus wrote about the "Third India." He recorded many imaginative stories about the land and its king, whom he said Europeans called Prester John.

After this, an African location for Prester John became more and more popular. This might have happened because Europe and Africa had more connections. For example, in 1428, the kings of Aragon (in Spain) and Ethiopia talked about a possible marriage between their kingdoms. On May 7, 1487, two Portuguese explorers, Pêro da Covilhã and Afonso de Paiva, were sent to find a sea route to India. They were also told to ask about Prester John. Covilhã reached Ethiopia. He was welcomed but not allowed to leave. Finding allies like Prester John increasingly encouraged early European exploration and colonialism. More explorers were sent in 1507. As a result, the regent queen of Ethiopia, Eleni of Ethiopia, sent an ambassador named Mateus to the king of Portugal and the pope. She was looking for an alliance against Muslim expansion. Mateus returned with a Portuguese embassy and a priest named Francisco Álvares in 1520. Álvares's book, which included Covilhã's story, was the first direct account of Ethiopia. It greatly increased European knowledge at the time.

By the time Emperor Lebna Dengel and the Portuguese made official contact in 1520, Prester John was the name Europeans used for the Emperor of Ethiopia. However, the Ethiopians themselves had never called their emperor that. When ambassadors from Emperor Zara Yaqob attended a church meeting in Florence in 1441, they were confused. The Catholic leaders insisted that the Ethiopians refer to their ruler as Prester John. The ambassadors tried to explain that this title was not in Zara Yaqob's list of names. But their warnings did little to stop Europeans from calling the King of Ethiopia Prester John. Some writers who used the title knew it wasn't a real Ethiopian name. They used it simply because their readers would know it.

For many years, people claimed Ethiopia was the origin of the Prester John legend. But most modern experts believe the legend was simply changed to fit Ethiopia. This is similar to how it was linked to Ong Khan and Central Asia in the 1200s. Modern scholars find nothing in the early stories about Prester John that would make Ethiopia a better fit than any other place. Also, experts in Ethiopian history have shown that the story wasn't widely known there until the Portuguese sailed around Africa to reach Ethiopia. In 1751, a Czech traveler asked Emperor Iyasu II about this name. The emperor was "astonished" and said that the kings of Ethiopia had never called themselves by that name. This is thought to be the first time an Ethiopian ruler commented on the tale. They were likely unaware of the title until that question.

End of the Legend and Its Impact

In the 1600s, scholars like Hiob Ludolf showed that there was no real connection between Prester John and the Ethiopian rulers. The search for the legendary king slowly stopped. But the legend had influenced hundreds of years of European history. It encouraged explorers, missionaries, scholars, and treasure hunters.

The idea of finding Prester John eventually disappeared. But the stories continued to inspire people even into the 1900s. William Shakespeare's play Much Ado About Nothing (1600) mentions the legendary king. So does a play by Tirso de Molina. In 1910, the Scottish writer John Buchan used the legend in his book Prester John. This book was about a Zulu uprising in South Africa and was very popular.

Throughout the rest of the 1900s, Prester John appeared in adventure stories and comics. For example, Marvel Comics featured "Prester John" in Fantastic Four and Thor. He was also a supporting character in the DC Comics series Arak: Son of Thunder. Charles Williams, a writer from the 1900s, made Prester John a protector of the Holy Grail in his 1930 novel War in Heaven. Prester John and his kingdom are also in two books by Umberto Eco. In his 2000 novel Baudolino, the main character helps write the "Letter of Prester John." In another book, Eco says the letter "served as an alibi for the expansion of the Christian world."

In 1986, writer Avram Davidson published an essay and a short story about Prester John. The short story imagined Prester John's kingdom still secretly ruled by his descendant.

In 1988, the fantasy novel The Dragonbone Chair used the name Prester John for the High King of its fantasy world.

He is also mentioned in the comic book series Fables. The recently deceased king in Tad Williams' "Memory, Sorrow and Thorn" fantasy books is named "Prester John."

The first song from the band Animal Collective's 2022 album Time Skiffs is called "Prester John."

Heraldry

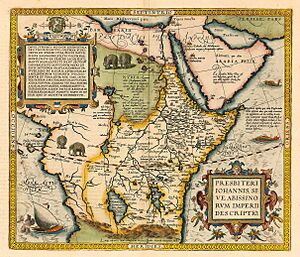

Different coats of arms have been given to Prester John in stories. In Canterbury Cathedral, a carving shows Prester John with a blue shield and a golden cross. In the 1500s, a mapmaker named Abraham Ortelius drew a map of John's empire in Africa. It showed a lion holding a cross.

See also

In Spanish: Preste Juan para niños

In Spanish: Preste Juan para niños

- Eldad ha-Dani

- Wandering Jew

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |