Martin Waldseemüller facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Martin Waldseemüller

|

|

|---|---|

Martin Waldseemüller (19th-century painting)

|

|

| Born | c. 1470 Wolfenweiler

|

| Died | 16 March 1520 (aged 49–50) Sankt Didel

|

| Alma mater | University of Freiburg |

| Occupation | Cartographer |

| Movement | German Renaissance |

Martin Waldseemüller (around 1470 – March 16, 1520) was a German mapmaker and a smart scholar known as a humanist. Sometimes people called him by his Latin name, Hylacomylus. His maps were very important and influenced other mapmakers of his time.

He and his friend Matthias Ringmann were the first to use the word America to name a part of the New World. They did this to honor the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci. Waldseemüller was also the first to map South America as its own continent, separate from Asia. He was also the first to create a printed globe and a large printed wall map of Europe. A collection of his maps, printed in 1513, is seen as the first example of a modern atlas.

Contents

Life of a Mapmaker

Not much is known about Martin Waldseemüller's early life. He was born around 1470 in a German town called Wolfenweiler. His father was a butcher. Around 1480, his family moved to Freiburg im Breisgau.

Records show that Waldseemüller went to the University of Freiburg in 1490. There, a famous scholar named Gregor Reisch was one of his teachers. After university, he lived in Basel. He became a priest there. It seems he also learned a lot about printing and engraving by working with printers in Basel.

Around 1500, a group of smart scholars formed in Saint-Dié-des-Vosges. They were supported by René II, Duke of Lorraine. This group called themselves the Gymnasium Vosagense. Their leader was Walter Lud. They wanted to publish a new version of an old map book called Ptolemy's Geography.

Waldseemüller was asked to join the group because of his mapmaking skills. It's not clear how they found him, but Lud later called him a "master cartographer." Matthias Ringmann also joined. He knew a lot about the Geography and spoke Greek and Latin. Ringmann and Waldseemüller soon became good friends and worked together.

The 1507 World Map

In 1506, the Gymnasium group got a French translation of something called the Soderini Letter. This booklet was said to be from Amerigo Vespucci. It told an exciting story about four trips Vespucci supposedly made to explore the coast of new lands in the western Atlantic Ocean.

The scholars thought this was the "new world" that old writers had talked about. The Soderini Letter gave Vespucci credit for finding this new continent. It also suggested that new Portuguese maps were based on his trips.

So, the group decided to pause their work on the Geography. Instead, they published a short book called Introduction to Cosmography with a new world map. Ringmann wrote the Introduction, which included a Latin translation of the Soderini Letter. In the introduction, Ringmann wrote:

"I see no reason why anyone could properly disapprove of a name derived from that of Amerigo, the discoverer, a man of sagacious genius. A suitable form would be Amerige, meaning Land of Amerigo, or America, since Europe and Asia have received women's names."

While Ringmann wrote the book, Waldseemüller worked on creating a world map. He used many different sources for his map. These included older maps by Ptolemy, Henricus Martellus, Alberto Cantino, and Nicolò de Caverio.

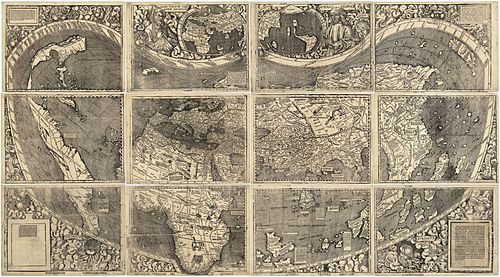

Besides a large 12-panel wall map, Waldseemüller also made a smaller, simpler globe. The wall map had big pictures of Ptolemy and Vespucci. Both the map and the globe were special because they showed the New World as a continent separate from Asia. They also named the southern landmass "America."

By April 1507, the map, globe, and the book Introduction to Cosmography were published. A thousand copies were printed and sold all over Europe.

The Introduction and map were very successful. Four editions were printed in the first year alone. Universities used the map widely. Other mapmakers admired the skill that went into making it. In the years that followed, other maps were printed that often used the name America. Even though Waldseemüller meant the name only for a part of Brazil, other maps applied it to the entire continent. In 1538, Gerardus Mercator used "America" for both the North and South continents on his famous map. By then, the name was firmly set for the New World.

Ptolemy's Geography (1513)

After 1507, Waldseemüller and Ringmann kept working together on a new edition of Ptolemy's Geography. In 1508, Ringmann traveled to Italy. There, he got a Greek copy of Geography. With this important reference, they made good progress. Waldseemüller was able to finish his maps.

However, the project was delayed when their supporter, Duke René II, died in 1508. The new edition was finally printed in 1513 by Johannes Schott in Strasbourg. By then, Waldseemüller had left the project. He was not given credit for his map work in the final book. Still, his maps were seen as very important contributions to mapmaking. They were used as a standard reference for many decades.

About twenty of Waldseemüller's "modern maps" were included in the new Geography. They were in a separate section called Claudii Ptolemaei Supplementem. This section is considered the first modern atlas. Maps of Lorraine and the upper Rhine region were the first printed maps of those areas. Waldseemüller probably made them based on his own surveys.

The world map published in the 1513 Geography suggests that Waldseemüller had changed his mind. He seemed to have doubts about the name and nature of the lands found in the western Atlantic. The New World was no longer clearly shown as a separate continent from Asia. The name America had been replaced with Terra Incognita (Unknown Land). We don't know why he made these changes. Perhaps he was influenced by people who said Vespucci had taken credit that belonged to Columbus for the discovery.

Other Important Works

Waldseemüller was also interested in surveying and the tools used for it. In 1508, he wrote a paper about surveying and perspective. This was for the fourth edition of Gregor Reisch’s Margarita Philosophica. He included a drawing of an early version of a theodolite. This is a surveying tool he called the polimetrum.

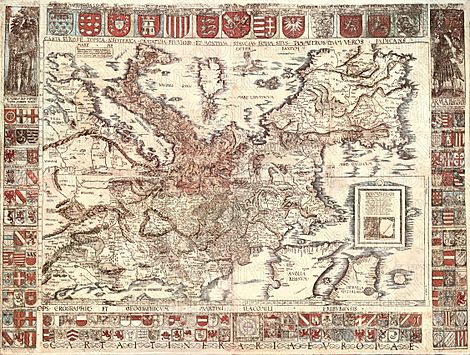

In 1511, he published the Carta Itineraria Europae. This was a road map of Europe. It showed important trade routes. It also showed pilgrim routes from central Europe to Santiago de Compostela, Spain. It was the first printed wall map of Europe.

In 1516, he made another large wall map of the world. It was called the Carta Marina Navigatoria. It was printed in Strasbourg. This map was designed like portolan charts, which were detailed sea maps. It was made of twelve printed sheets.

The Paris Green Globe (or Globe vert) has been said to be made by Waldseemüller. Experts at the Bibliothèque Nationale believe this. However, not everyone agrees with this idea.

Waldseemüller died on March 16, 1520, in Saint-Dié-des-Vosges in eastern France. He did not leave a will. He had been a priest there since 1514.

The 1507 Map Found Again

The 1507 wall map was lost for a long time. But a copy was found in Schloss Wolfegg in southern Germany by Joseph Fischer in 1901. It is the only known copy of this map. The United States Library of Congress bought it in May 2003.

Five copies of Waldseemüller's globe map still exist. These are in the form of "gores." Gores are printed map sections that were meant to be cut out and glued onto a wooden globe.

See also

In Spanish: Martin Waldseemüller para niños

In Spanish: Martin Waldseemüller para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |