Battle of Bicocca facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Bicocca |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian War of 1521–26 | |||||||

Lombardy in 1522. The location of the battle is marked. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 19,000–31,000+ | 18,000+ | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,000+ killed | 1–200 killed | ||||||

The Battle of Bicocca (also called La Bicocca) happened on April 27, 1522. It was a major fight during the Italian War of 1521–26. In this battle, a combined army from France and Venice, led by Odet de Foix, Vicomte de Lautrec, lost badly. They were defeated by an army from the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and the Papal States, commanded by Prospero Colonna.

After the battle, Lautrec and his forces left Lombardy. This meant the Duchy of Milan came under the control of the Holy Roman Empire. The battle is important because it showed the end of the Swiss mercenaries' main power in infantry warfare. It was also one of the first battles where firearms played a very important role.

Contents

How the Battle Started

In 1521, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Pope Leo X decided to attack the Duchy of Milan. Milan was a key French area in Italy. A large army, including Papal, Spanish, and Imperial troops, gathered near Mantua. This army was led by Prospero Colonna.

For several months, Colonna avoided big battles. He would surround cities but not attack directly. Meanwhile, the French army, led by Lautrec, started losing many soldiers. Many Swiss mercenaries left because they weren't getting paid.

Colonna saw his chance. He moved his army and surprised the French in Milan. Lautrec had to retreat to Cremona with about 12,000 men. By early 1522, the French had lost several cities like Alessandria and Pavia.

Lautrec then got more soldiers, including 16,000 new Swiss pikemen. He also got help from Giovanni de' Medici and his famous "Black Bands." The French tried to attack Novara and Pavia to make Colonna fight. But Colonna stayed in a strong position near Certosa.

Lautrec then tried to cut off Colonna's supplies by moving around Milan to Monza. However, the Swiss soldiers in Lautrec's army caused a problem. They demanded their pay and insisted on fighting immediately. If not, they would leave. Lautrec had no choice but to agree and marched towards Milan.

The Battle Begins

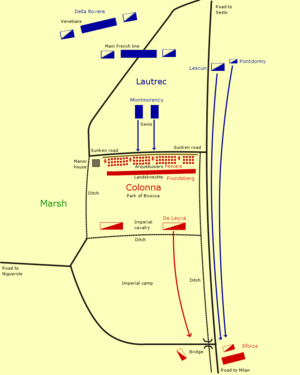

Colonna had moved his army to a very strong place: the park of Bicocca, north of Milan. This park was protected by marshy ground on one side and a deep ditch on the other. A narrow stone bridge crossed the ditch. The north side of the park had a sunken road, which Colonna made even deeper. He also built a dirt wall (rampart) behind it.

Behind this wall, Colonna placed his best soldiers. There were four lines of Spanish arquebusiers (soldiers with early firearms) led by Fernando d'Ávalos. Behind them were blocks of Spanish pikemen and German landsknechts (mercenaries). The Imperial artillery (cannons) was placed to fire across the open fields in front of the park.

On the evening of April 26, Lautrec sent scouts to check Colonna's positions. Colonna knew the French were coming and asked for more troops from Milan. The next morning, Francesco II Sforza arrived with 6,400 more soldiers.

At dawn on April 27, Lautrec began his attack. He sent the Black Bands forward to clear the way. The main attack was by two columns of Swiss soldiers, each with 4,000 to 7,000 men. They were supposed to attack the front of Colonna's camp directly. Meanwhile, a group of French cavalry (horse soldiers) tried to go around the camp to attack the bridge from behind.

The rest of the French army, including their infantry and most of their heavy cavalry, stayed behind the Swiss columns. Behind them were the Venetian forces.

The Swiss Attack

Anne de Montmorency was in charge of the Swiss attack. He told them to wait for the French cannons to fire first. But the Swiss refused. They were very confident and rushed forward, leaving their own cannons behind. They quickly came under heavy fire from the Imperial artillery. Many Swiss soldiers were killed before they even reached the enemy lines.

The Swiss columns stopped suddenly when they reached the sunken road. The road was too deep, and the dirt wall behind it was too high. Their long pikes couldn't reach the enemy. As they tried to cross the road, they suffered huge losses from the Spanish arquebusiers. Some Swiss managed to climb the wall, but they were met by the German landsknechts. The Swiss were pushed back into the sunken road.

After trying to break through for about half an hour, the remaining Swiss soldiers retreated. They had lost more than 3,000 men, including many of their leaders. Of the French nobles who joined the attack, only Montmorency survived.

After the Main Attack

While the Swiss were attacking, the French cavalry tried to cross the bridge south of the park. They managed to get into the Imperial camp. Colonna sent some cavalry to stop them, and Sforza's troops also moved to surround them. The French cavalry fought their way out and rejoined the main army.

Even though the French had been hurt, Colonna decided not to launch a full counter-attack. He believed the French were already defeated and would soon leave. He was right. The Swiss soldiers refused to fight anymore and left for home on April 30.

Lautrec realized his army was too weak without the Swiss infantry. He retreated to Venetian territory. From there, he left for France, leaving the rest of his army to his commander, Lescun.

What Happened Next

Lautrec's departure meant the French lost their hold on northern Italy. Colonna and d'Avalos then marched on Genoa and captured it quickly. Lescun, seeing that Genoa was lost, made a deal with Sforza. The French gave up the Castello Sforzesco in Milan and left Italy.

The Venetians, led by their new leader Andrea Gritti, no longer wanted to fight. In July 1523, they made a peace treaty with Charles V. The French tried two more times to get back Lombardy, but they failed. The Treaty of Madrid, signed after Francis lost the Battle of Pavia, left Italy firmly in Imperial hands.

The Battle of Bicocca also changed how people viewed Swiss soldiers. Before, they were seen as unstoppable. But after Bicocca, their willingness to make direct, head-on attacks decreased. They still fought in wars, but they were not as bold as before.

The battle also showed how important small arms like the arquebus were becoming. Even though the full power of the arquebus was shown later, it became clear that armies needed these firearms. The combination of pikemen and arquebusiers became the standard way to organize infantry. This "pike and shot" method lasted for a long time. Frontal attacks on strong, dug-in positions became too costly and were rarely tried again in the Italian Wars.

Because of this battle, the word bicoca entered the Spanish language. It means a bargain, or something gained easily and cheaply.

Images for kids

-

Lombardy in 1522. The location of the battle is marked.

-

Anne de Montmorency, painted by Jean Clouet (c. 1530). Montmorency was the only French noble to survive the Swiss attack.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Bicoca para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Bicoca para niños