Anne de Montmorency, 1st Duke of Montmorency facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Anne de Montmorency |

|

|---|---|

| 1st Duc de Montmorency Constable of France Grand Maître of France |

|

|

|

| Portrait by Corneille de Lyon | |

| Spouse(s) | Madeleine de Savoie |

| Issue | |

|

|

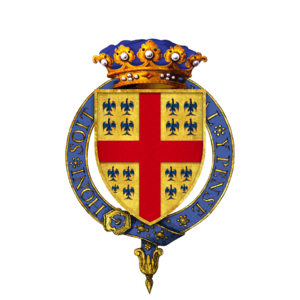

| Noble family | Montmorency |

| Father | Guillaume de Montmorency |

| Mother | Anne de Saint-Pol |

| Born | c. 1493 Chantilly |

| Died | 12 November 1567 Paris |

Anne de Montmorency (born around 1493, died 12 November 1567) was a very important French nobleman and military leader. He served five different French kings: Louis XII, François I, Henri II, François II, and Charles IX. He was a powerful figure during a time of many wars in France, including the Italian Wars and the early French Wars of Religion.

Anne de Montmorency started his career in the army under King Louis XII. He became a close friend of King François I, who helped him rise through the ranks. He was made a Marshal of France in 1522 and later became Grand Maître, which meant he was in charge of the king's household. In 1538, he became Constable of France, the highest military position in the country. This made him the supreme commander of the French army.

However, he faced challenges and was sometimes out of favor with the king. He was even captured twice during battles: at the Battle of Pavia in 1525 and the Battle of Saint-Quentin in 1557. After the death of King Henri II, Montmorency lost some of his power but later returned to a central role in the government. He formed an alliance with his former rival, the Duke of Guise, to protect Catholicism in France. He died in 1567 from wounds received in the Battle of Saint-Denis.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Anne de Montmorency was born in 1493 in Chantilly. His parents were Guillaume de Montmorency and Anne de Saint-Pol. He was named after his godmother, Anne of Brittany, who was the Queen of France. His father, Guillaume, held an important position in the household of the future King François I.

The Montmorency family was very proud of being one of the oldest and most important noble families in France. They believed they were more important than many other noble families, even those who were princes.

Marriage and Children

Anne de Montmorency married Madeleine de Savoie on 10 January 1527. Madeleine was a cousin of King François I. Their wedding was a grand event, celebrated by the king himself. This marriage helped Montmorency become even more connected to the royal family. Madeleine also brought family lands in Picardie to the marriage.

Anne and Madeleine had many children:

- Éléonore de Montmorency (1528–1556)

- Jeanne de Montmorency (1529–1596)

- François de Montmorency (1530–1579), who became a Marshal and Duke

- Catherine de Montmorency (1532–1595)

- Henri I de Montmorency (1534–1614), who also became a Duke and Constable of France

- Charles de Montmorency (1537–1612), who became a Duke

- Gabriel de Montmorency (1541–1562)

- Guillaume de Montmorency (1544–1591)

- Marie de Montmorency (1547–1572)

- Louise de Montmorency, who became an abbess

Several of Montmorency's sons were raised alongside the royal children. He also arranged important marriages for his daughters into powerful noble families. His sons were all trained for military careers.

Anne had strong ideas about his children's marriages. His eldest son, François, wanted to marry someone Anne did not approve of. To prevent this, Anne helped pass a law in 1557. This law allowed fathers to disinherit sons under 30 or daughters under 25 who married without their parents' permission. This forced his son to end his engagement and marry Diane de France, which further linked the Montmorency family with the royal family.

Relatives and Religion

Anne's sister, Louise de Montmorency, secretly became a Protestant. She married Gaspard I de Coligny. After her husband died, Anne and Louise raised her sons together. These nephews, Gaspard de Coligny, Odet de Coligny, and François de Coligny, later became important Protestant leaders during the French Wars of Religion. Gaspard became Admiral of France, a very high military rank.

Anne de Montmorency and his wife were strong Catholics. They were not happy about his sister and nephews becoming Protestants. However, Anne cared deeply about his family. Even though he was a strong Catholic, he did not immediately oppose his nephews because of their religion. He believed that as long as they publicly followed the Catholic faith, their private beliefs were their own business.

Anne suffered from Gout in his later years. He was known as a quiet and serious man, a "bluff soldier" who was traditional in his ways.

Wealth and Estates

Anne de Montmorency was one of the wealthiest non-royal people in France. By 1560, his various jobs brought him an annual income of 32,000 livres (French pounds). When including the income from his many lands, his total income was around 180,000 livres in 1548. This was much more than even some princes of the royal family. By the end of his life in 1567, his pensions and land income were still very high.

The Montmorency family owned over 600 fiefs (lands) across France. They also had more supporters and followers than any other private family in the kingdom. His lands were spread across many regions, including the Île de France, Picardie, and Normandie.

Châteaux and Residences

The Montmorency family owned grand estates in the Île de France, including the famous Château d'Écouen and Château de Chantilly.

Anne oversaw the building of Château d'Écouen starting in 1538. Chantilly was also renovated under his direction from 1527 to 1532. Écouen was a beautiful example of the new architectural style of the time. It featured sculptures by Jean Goujon and was designed by Jean Bullant. It even held two statues by Michelangelo, which King François I had given to Montmorency. Chantilly was so grand that it rivaled a royal palace.

These were two of his seven main castles. The royal family sometimes stayed at his châteaux. For example, King Charles IX and his mother Catherine de' Medici stayed at Châteaubriant in 1565.

In Paris, Anne owned four large residences called hôtels. One of them had a special room for listening to music, showing his interest in culture.

Patron of the Arts

Anne de Montmorency supported artists. He commissioned the famous painter Léonard Limousin to create an enamel dish. The artist Rosso Fiorentino also created a famous painting called the Pietà for him in 1538, which is now in the Louvre Museum. His castles also had large libraries filled with books. Anne collected antiques and weapons, which he kept in his châteaux.

Childhood Friends

In his youth, Anne de Montmorency was a playmate of the future King François I. They played sports together, along with another future important courtier, Philippe de Chabot.

Early Career and Rise to Power

Serving King François I

Anne de Montmorency first served in the military in 1511 under King Louis XII. He fought in the important Battle of Ravenna in 1512.

When François I became king in 1515, he wanted to reclaim French lands in Italy. Montmorency joined the campaign and showed great bravery at the Battle of Marignano in 1515. By 1516, at just 23 years old, he was already a captain and governor of the Bastille in Paris and Novara in Italy.

In 1518, Montmorency was sent to England as a hostage to ensure peace treaties between France and England were followed. This was a common practice at the time. Around 1520, he became the "first gentleman of the king's chamber," giving him special access to the king. In 1521, he helped defend the city of Mézières during a siege by an Imperial army.

Becoming a Marshal

In August 1522, Anne de Montmorency was made one of the Marshals of France, a high military rank. He also became a royal advisor and was inducted into the Ordre de Saint-Michel, a prestigious order of knights.

He fought in Italy in the Battle of La Bicocca in 1522, which was a defeat for the French. Montmorency and many French nobles fought bravely but suffered heavy losses.

Bourbon's Betrayal and Pavia

In 1523, Constable Bourbon betrayed France and joined forces with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. England also declared war on France. Montmorency was tasked with raising a new army in the south of France. He gathered mercenaries and artillery, but King François I fell ill and had to return to Paris, leaving the army under another commander.

Montmorency led the army's advance into Italy, but he became very ill with the plague and had to be carried in a litter. The French army was forced to retreat in April 1524.

The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V then invaded France from Italy in late 1524, led by the traitor Bourbon. Bourbon's army got stuck besieging Marseille. King François I gathered a strong army, and Montmorency pursued Bourbon's retreating forces. François then followed Montmorency back into Italy.

King François I decided to besiege Pavia. In February 1525, the Imperial army forced a battle. The Battle of Pavia was a huge disaster for the French. King François I, Montmorency, and many other important nobles were captured.

Montmorency was allowed to leave captivity early to help raise money for his own ransom and for the king's release. He met with the royal family and assured them the king was well. He was later exchanged for another prisoner.

King François I was eventually transferred to Spain as a captive. Montmorency worked to arrange a truce and for the king's sister to negotiate peace. The Emperor demanded a lot of land from France for the king's release. François I even considered giving up his throne to his son. In the end, the king was released in January 1526, but his two eldest sons had to go to Spain as hostages to guarantee the treaty. Montmorency brought the news of this treaty back to France.

Ascent to Power

Grand Master

In 1526, Anne de Montmorency was appointed governor of Languedoc. In the same year, he was made Grand Maître (Grand Master). This gave him supreme authority over the king's household and the court. He was in charge of royal appointments, court spending, and security. He also managed all communication with the king's sons who were held hostage in Spain.

In 1527, Montmorency was sent to England to strengthen the alliance between France and England. He awarded the French Order of Saint-Michel to King Henry VIII, and in return, King Henry awarded the English Order of the Garter to King François I.

Freeing the Princes

In December 1527, King François I called a meeting to raise money to ransom his sons from Spain. Montmorency was responsible for collecting money from some regions, and he insisted that they contribute their fair share.

Montmorency played a key role in the peace negotiations that began in July 1529 between King François I's mother, Louise de Savoie, and the Emperor's aunt, Margarete von Österreich. This agreement became known as the Paix des Dames (Peace of the Ladies). It set a huge ransom for the princes' freedom. France had to give up claims to some lands but kept others.

Montmorency was responsible for gathering the ransom money. By April 1530, a large amount of gold was ready. He then went to receive the princes and King François I's new wife, Eleanor of Austria, who was the Emperor's sister. The exchange of the princes for the money was a tense moment, but Montmorency managed it successfully.

Guardian of the Princes

In the years that followed, Montmorency dedicated himself to the young princes. As Grand Maître, he supervised their daily lives, their education, and taught them court ceremonies. He became a very important figure in their lives.

Montmorency was also close to the new Queen Éléonore and supported her at court. He oversaw the arrangements for her coronation.

His success in securing the princes' release greatly increased his standing at court.

Diplomat and Military Leader

In 1532, Montmorency became a Knight of the Order of the Garter, an important English order of chivalry, during a meeting between the English and French kings.

He also played a crucial role in arranging the marriage between King François I's second son, the Duke of Orléans (future King Henri II), and Catherine de' Medici in 1533. Montmorency prepared Marseille for the Pope's arrival to finalize the marriage.

The Duke of Orléans later became interested in Diane de Poitiers, the king's mistress. Montmorency had a good relationship with Diane and even allowed their secret meetings to happen at his Château d'Écouen.

In 1534, Montmorency was given the task of raising 6,000 soldiers from Picardie to form a "legion." This force was used in the following years, though it sometimes had discipline problems.

Temporary Retirement

In the mid-1530s, Montmorency disagreed with the "war party" at court, led by Admiral Chabot, who wanted to attack the Emperor. Montmorency preferred peace. Because of this disagreement, he decided to retire to his estates at Chantilly in 1535. However, he kept all his titles and pensions.

He returned to the center of government in May 1536 when the Holy Roman Emperor invaded Provence. Montmorency was made "lieutenant-general," giving him wide powers to mobilize troops and command forces.

Provence Campaign

In July 1536, the Emperor's army invaded France. Montmorency led the defense in the south. He used a "scorched earth" strategy, destroying crops and supplies in Provence to deny them to the enemy. He also strengthened the defenses of Marseille. The Emperor's army suffered from disease and lack of food. By September, the Emperor decided to withdraw. Montmorency's leadership had successfully foiled the invasion.

In 1537, Montmorency led a successful campaign on France's northern border, recovering some lost towns. He then moved south to Italy, where he was made lieutenant-general of French Piemonte. He led a large army and successfully forced the Imperial forces to retreat.

Montmorency then helped negotiate a ten-year truce with the Emperor in 1537, which was finalized in 1538. He was greatly praised by the king for his efforts.

Constable of France

Highest Military Rank

On 10 February 1538, Anne de Montmorency was appointed Constable of France. This was the most senior military position in the kingdom, which had been vacant since Bourbon's betrayal. As Constable, he was the supreme commander of the French military, even outranking princes in battle. He also gained luxurious apartments in the royal palace. This appointment made him effectively the lieutenant-general of the kingdom.

His promotion was a reward for his successful defense of France against the invasion of Provence. During this time, he also became very close to the Dauphin (the king's eldest son), the future King Henri II.

Diplomatic Efforts for Milano

In July 1538, Montmorency attended important discussions between the Emperor and King François I. They talked about giving Milano (a rich Italian duchy) to the king's third son, the Duke of Angoulême, as a dowry for a marriage. Montmorency was very happy with the meeting, believing it would bring lasting peace. He was in charge of French foreign policy for the next two years, trying to secure Milano for France through diplomacy.

In 1539, Montmorency organized grand receptions for the Emperor as he traveled through France. The Emperor was even hosted at the Château de Fontainebleau for Christmas. Montmorency led the procession when the Emperor entered Paris in January 1540, carrying the sword of his office.

However, the Emperor later changed his mind about giving Milano to the French prince. Instead, he suggested other territories, but with conditions that were not favorable to France. This led to the collapse of talks by June 1540.

Loss of Favor

When the Emperor decided to give Milano to his own son in October 1540, King François I was furious. He blamed Montmorency for this diplomatic failure. Montmorency was forced to withdraw from court.

His influence continued to decline. By April 1541, he was at the mercy of the king's mistress, the Duchess of Étampes, who was his rival. In June 1541, the king publicly humiliated Montmorency by ordering him to carry the Queen of Navarre's daughter to the altar at a wedding. Montmorency realized his time of favor was over and left court the next day. He would not return during King François I's lifetime.

Years Out of Power

Governate Revoked

In May 1542, King François I abolished all governorships in France, then reappointed everyone except Montmorency, who was replaced as governor of Languedoc. This was seen as a direct attack on Montmorency's power.

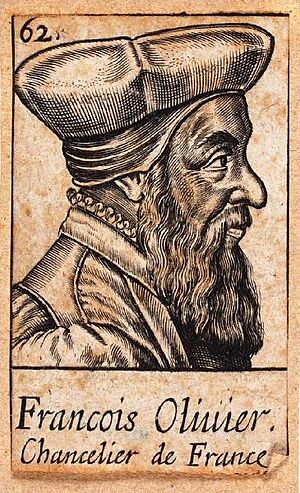

His disgrace also meant he could no longer protect his political allies, leading to the downfall of the Chancellor of France, Poyet. Meanwhile, his rival, Admiral Chabot, was brought back into favor.

Supporting the Dauphin

During his time out of power, Montmorency remained close to the Dauphin, the future King Henri II. The Dauphin was in a rivalry with his younger brother, who was allied with the king's mistress. The Dauphin wanted Montmorency to be recalled to court, but the king refused.

As King François I was dying, he asked his son not to bring Montmorency back to court. However, the Dauphin had already planned to restore Montmorency to all his offices upon his own ascent to the throne.

Return to Power

New King, New Government

King François I died on 31 March 1547. The new king, Henri II, immediately sent for Montmorency to return to court. They had a long meeting on 1 April, where they completely reorganized the government. Montmorency was given the apartments of the former king's mistress, who was banished from court.

Montmorency quickly became the head of the royal administration. He was restored to his positions as Constable and Grand Maître. His closeness to the new king was so great that he sometimes even shared the king's bed, which surprised some people at the time. He also received all the back pay he had missed during his disgrace.

Montmorency was restored as governor of Languedoc, and his brother was restored as governor of the Île de France and Paris. Montmorency also helped his nephews rise to important positions, strengthening his own power. For several years, all foreign ambassadors presented their credentials to Montmorency before meeting the king.

Royal Council and Influence

During Henri II's reign, a "council of affairs" met every morning with the king. It included Montmorency, the Lorraine brothers (his rivals), and other leading figures. This council made important decisions. Montmorency and the Chancellor François Olivier worked closely together, often against the influence of the Lorraine family.

Montmorency held the most senior position on the royal council. He was like a prime minister, overseeing much of the government's work. He also had his own trusted secretaries who helped him manage correspondence and affairs.

Some people at the time believed that King Henri II was not very interested in governing and allowed Montmorency and other powerful figures to run things. It was even said that the king sometimes trembled when Montmorency approached, "as children do when they see their schoolmaster."

Gabelle Revolt

In 1548, a large revolt against the gabelle (salt tax) broke out in southwestern France. King Henri II decided that a harsh punishment was needed. Montmorency argued for a very extreme response, but the king rejected it. Montmorency and the Duke of Aumale (later Duke of Guise) were sent to suppress the rebellion.

Montmorency entered Bordeaux with his forces in October. He disarmed the city and suppressed the revolt with great severity. He had 150 leaders executed, and his soldiers looted the city. He suspended the local court and imposed a large fine on the city.

However, the harshness was short-lived. Due to tensions with England, the city's privileges were restored, and the fines were canceled after six months. The unpopular salt tax changes were also mostly reversed.

Recapturing Boulogne

Both Montmorency and the Lorraine family agreed on the importance of recapturing Boulogne from the English. Montmorency helped plan the campaign. In 1549, he led forces to besiege English strongholds around Boulogne. His forces captured Ambleteuse and then blockaded Boulogne itself.

The English were willing to negotiate. Montmorency's brother and nephew led the French delegation for peace talks. In February 1550, a treaty was signed. The English agreed to return Boulogne to France for a payment. Montmorency's efforts were key to this success.

As a celebration of the victory, King Henri II organized a triumph in Rouen. Montmorency and the Duke of Guise (who had just become Duke after his father's death) had important places in the parade.

Becoming a Duke

In July 1551, Anne de Montmorency was elevated from a simple baron to a Duke and Peer of France. This was a very high honor, placing him among the highest nobility. This extraordinary promotion was given because of his personal qualities, his family's long history, and his recent success in recapturing Boulogne.

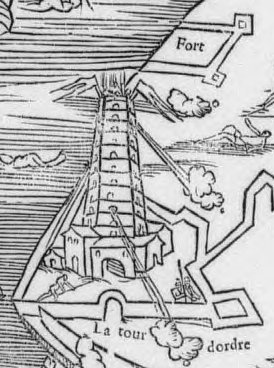

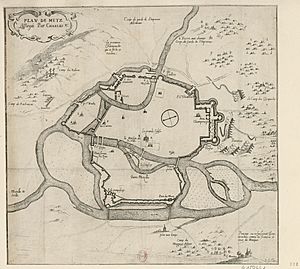

Metz Campaign

Montmorency encouraged King Henri II to support Protestant German princes who were resisting the Emperor. A treaty was signed in 1552, allowing France to occupy the Imperial cities of Cambrai, Metz, Toul, and Verdun.

In March 1552, a large French army was assembled. Montmorency was given formal command. He secured Toul and then approached Metz. He convinced the city council to allow French troops to occupy Metz, claiming it was to protect German liberties. King Henri II arrived in Metz on 17 April.

After Metz was secured, Montmorency continued campaigning, capturing other strongholds. However, the Emperor was determined to retake Metz. In November 1552, the Imperial army, led by the Emperor himself, besieged Metz. Montmorency ordered a "scorched earth" policy around Metz to starve out the Imperial army.

The siege of Metz lasted until December 1552, when the Emperor gave up, having lost many men. This successful defense made the Duke of Guise very famous, as he led the city's defense. Montmorency was pleased with the success of his strategy to starve the enemy.

Northern Campaigns

In 1553, Montmorency was partly blamed for the French defeat at Thérouanne, where his eldest son was captured. He was also criticized for not following up the victory at Metz with a decisive blow against the Emperor. Montmorency and the king raised a large army for a counter-offensive. They devastated the countryside and tried to besiege Cambrai, but the campaign was cut short due to bad weather and Montmorency falling seriously ill.

In 1554, the French army again campaigned in the north. Montmorency's army captured Mariembourg and Bouvignes. They continued to advance, burning villages, all the way to Bruxelles. They then besieged Renty, but the Imperial army was also in the area. After some fighting, Renty remained untaken. The king decided to retreat the army back to France.

Montmorency was criticized for his cautious approach during this campaign. Some accused him of being more interested in securing his son's release from captivity than in winning battles.

Seeking Peace

Montmorency was made godfather to King Henri II's youngest son in 1555, showing his continued high standing. The Île de France region became increasingly important to the Montmorency family. He secured the governorship of the province for his eldest son. However, the Lorraine family also bought lands in the region, leading to rivalry between the two powerful families.

Negotiations for Peace

Montmorency strongly desired peace with the Holy Roman Empire, especially since his son and nephew were still captives. He met with the Pope's representative to discuss peace terms. However, talks broke down because the Imperial side demanded too much from France.

At the French court, there was a sharp division between the Lorraine brothers, who wanted to continue the war in Italy, and Montmorency, who saw it as too expensive and risky. Montmorency disapproved of their "adventurism."

In October 1555, Emperor Charles V began to give up his control of his vast empire, passing it to his son Philip. This helped peace talks, as King Henri II had less personal animosity towards Philip. Montmorency pushed for peace, and his nephew Coligny led the French talks.

Truce of Vaucelles

Montmorency successfully arranged the Truce of Vaucelles, signed on 5 February 1556, between France, the Empire, and Spain. This truce was a big victory for France, allowing the king to keep control of Metz, Toul, Verdun, and other captured territories. It also helped Montmorency negotiate the release of his son from captivity.

However, Montmorency faced criticism for his role in securing peace. Some accused him of being afraid that if the war continued, more aggressive military leaders like the Duke of Guise would replace him in the king's favor.

The Truce of Vaucelles did not last its intended five years. It was broken in September 1556 when the Pope pushed King Henri II to go back to war against Spain in Italy. Montmorency argued against returning to war, but the king eventually agreed to an Italian expedition.

Persecution of Protestants

The growth of Protestantism, especially in Béarn under the Queen of Navarre, concerned Montmorency. He supported efforts to combat what he saw as "heresy."

In July 1557, an edict established the Inquisition in France. Three "inquisitors" were chosen from the leading families: Cardinal de Lorraine, Cardinal de Châtillon (Montmorency's nephew), and Cardinal de Bourbon. It's interesting that Montmorency's nephew, who was suspected of Protestant sympathies, was included.

The Duke of Guise led a disastrous campaign in Italy in 1557. At court, Cardinal de Lorraine complained that he had to spend all his time with the king to prevent Montmorency from convincing the king to end the invasion.

Disaster at Saint-Quentin

In May 1557, Montmorency was put in command of the northern frontier army. While the Duke of Guise was in Italy, a Spanish army invaded France from the Spanish Netherlands and besieged Saint-Quentin. Montmorency led an army to relieve the town, but he was outnumbered. On 10 August, he suffered a crushing defeat in front of Saint-Quentin. His army was destroyed, and Montmorency himself was captured for the third time in his career. His fourth son was killed in the battle.

This defeat was a disaster for France. King Henri II lacked troops and generals. The capital, Paris, was vulnerable. People blamed Montmorency for his incompetence. The Duke of Guise was quickly recalled from Italy and made lieutenant-general of the kingdom to manage the emergency. Montmorency's nephew, Coligny, also fell into Spanish hands during the fall of Saint-Quentin and later converted to Protestantism in prison.

Captivity and Peace Negotiations

King Henri II was very anxious about Montmorency's captivity and wanted him back at court. He was also concerned about the growing power of the Lorraine family in Montmorency's absence. Meanwhile, the Duke of Guise captured Calais from England in January 1558, making him a national hero.

Montmorency was held captive in Ghent. From prison, he tried to facilitate peace by proposing marriage alliances between the French and Spanish royal families. His efforts were aimed at reducing the influence of the Lorraine family.

His ransom was set at a very high amount. The first payment was made in late 1558, and Montmorency was released. King Henri II was overjoyed to see him, and they spent two days together, with Montmorency sleeping in the king's chamber. Montmorency complained about the ambition of the Lorraines, and the king agreed.

Return to Power and Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis

With his ransom paid, Montmorency returned to the center of political power in December 1558. He quickly re-established his dominance at court. The Duke of Guise's authority as lieutenant-general was canceled.

Montmorency, along with other key figures, began formal peace talks in October 1558. The negotiations were difficult, with the Habsburgs (Spanish and Imperial side) demanding many French territories. Montmorency argued against giving up Piemonte, but eventually, the king decided to make peace, even if it meant giving up many French conquests in Italy. Montmorency was blamed by the "war party" for this approach, but King Henri II defended him.

On 4 April 1559, the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis was signed. It was two separate treaties: one between France and Spain, and another between France and England. France kept Calais, Metz, Toul, Verdun, and some towns in Piemonte, but returned other conquests. This peace was deeply resented by many French military leaders.

Montmorency then worked to foster friendship with England. He also signed an agreement for the release of common prisoners of war.

Persecution of Heresy

On 10 June 1559, King Henri II visited the Paris Parlement (highest court) to observe its session. He was concerned about Protestants in the court. Montmorency and the Lorraine brothers accompanied him. During the session, some deputies, including Anne du Bourg, spoke out in ways that angered the king. As a result, eight deputies were arrested, and Anne du Bourg was later burned at the stake.

The king was determined to strengthen measures against Protestantism. A new edict to increase persecution was created at Montmorency's Château d'Écouen, showing his continued influence.

Loss of Power

Death of the King

On 30 June 1559, King Henri II was participating in a jousting tournament to celebrate the peace treaty. His opponent's lance pierced his visor, fatally injuring his eye. Montmorency and others rushed to his side. In the following days, Henri II slowly died. During his periods of unconsciousness, Queen Catherine kept Montmorency away, but when conscious, the king called for him.

As Grand Maître, Montmorency had an important role in the events after the king's death, including the funeral preparations.

Palace Revolution by the Lorraine Brothers

With King Henri II dead, the Lorraine family quickly took advantage of their closeness to the new, young King François II. Montmorency was busy with his duties guarding the late king's body, while the Lorraine brothers took control of the Louvre palace and the young king. Queen Catherine supported the Lorraines against Montmorency, whom she disliked.

At the king's funeral, Montmorency had the duty to declare, "The king is dead. Long live king François, second of his name, by the grace of God most Christian king of France." The Duke of Guise then raised the royal standard, showing his new power.

The Lorraines asserted control over the military, church, and finances. On 11 July 1559, Montmorency was told that the king wished for Guise to handle military affairs and Lorraine to handle finances. Montmorency was told his presence at court was unnecessary. The young king, François II, had disliked Montmorency.

Montmorency urged the King of Navarre to come to court to form a united front against the Lorraine government, but Navarre hesitated. On 17 November 1559, Montmorency was officially removed from the office of Grand Maître, which was given to the Duke of Guise. He did, however, keep his title of Constable and governor of Languedoc.

Retirement from Court

With little access to power, Montmorency withdrew to his estates. He told the king he was "old and tired." In 1560, no court appointments were made with his backing, while the Lorraine brothers were responsible for most of them.

The new government faced a financial crisis and reclaimed some royal lands that had been given away. Montmorency lost some valuable lands he had received earlier.

Conspiracy of Amboise

In March 1560, a Protestant conspiracy tried to kidnap the king. Even though Montmorency was out of power, he did not get involved in the plot. He and his son helped organize security measures in Paris to prevent the city from falling to any conspiracy.

The coup failed. Montmorency had to defend his innocence before the Parlement, where he criticized the conspiracy and subtly attacked the Lorraine government.

Return to Power (Again)

Death of François II and New Order

King François II died suddenly on 5 December 1560. Queen Catherine de' Medici became regent for her young son, Charles IX, who was only 10 years old. The King of Navarre became lieutenant-general of the kingdom, gaining overall military authority. Montmorency was also an important part of this new government.

The King of Navarre tried to assert his new authority, demanding that the Duke of Guise be removed from court and give up the office of Grand Maître. Catherine, fearing for her own position, convinced Montmorency to stay at court. In this new arrangement, Catherine, Navarre, Montmorency, and his nephew Coligny were the main decision-makers. The Lorraine family lost their power.

Montmorency returned to living in the Louvre palace. However, another important figure, Saint-André, worked to turn Montmorency against his Protestant-leaning nephews, especially Coligny.

Formation of the 'Triumvirate'

During Easter 1561, some nobles feared that the royal family was becoming Protestant. This, along with the presence of Protestant leaders like Condé and Coligny in the royal council, greatly worried Montmorency about the kingdom's religious direction.

As a result, Montmorency formed an alliance with his great rival, the Duke of Guise, and Saint-André. This alliance, known as the 'Triumvirate', was formed on 8 April 1561 to protect Catholicism and suppress "heresy." The reconciliation between Montmorency and Guise was overseen by Cardinal de Tournon. Montmorency was motivated by his resentment that he had not been fully restored as the prime courtier after François II's death, a position given to Navarre instead.

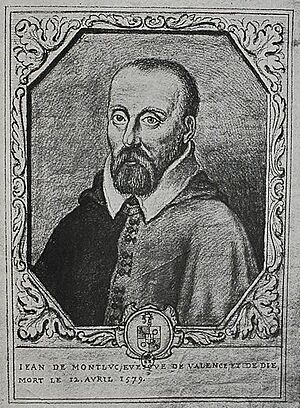

The first sign of this new Catholic alliance was when Montmorency and Guise refused to attend an Easter sermon given by Jean de Monluc, whose sermons often criticized Catholic practices. Instead, they attended a more traditional mass. They also sought support from King Philip II of Spain.

Opposition to Government and Toleration Policy

This new alliance pushed Queen Catherine closer to her Protestant advisors. Montmorency broke from his nephews, favoring the Lorraine family. He reprimanded his nephew Coligny for allowing Protestant preaching in his quarters at court. Montmorency's wife also encouraged him in this new alliance, arguing that Coligny had betrayed Montmorency's interests by promoting Protestantism.

After the failure of the Colloquy of Poissy to unite Protestants and Catholics, the "Catholic party" further distanced itself from court. Montmorency joined a mass exodus of nobles from court in October 1561, leaving the royal council mostly Protestant.

Montmorency was present at an assembly in January 1562 that tried to solve the religious question. The assembly voted against granting Protestants temples, but a majority supported allowing Protestant worship. As a result, Catherine issued the Edict of Saint-Germain on 17 January, which granted limited toleration to Protestants.

By early 1562, the King of Navarre had been won over to the Catholic opposition. When Catherine tried to remove Montmorency from court, Navarre insisted that Montmorency's Protestant nephews also be removed. Montmorency then left court himself.

French Wars of Religion

Massacre of Wassy and Securing the Royal Family

On 1 March 1562, the Duke of Guise and his men were involved in the Massacre of Wassy, where many Protestant worshippers were killed. Guise then marched to Paris, where he was met by Montmorency and Saint-André. They entered Paris in a grand procession on 16 March, joined by the King of Navarre, giving their cause legitimacy.

This entry into Paris was against Queen Catherine's wishes. The three "Triumvirs" then wrote to Catherine, explaining they would stay in Paris to prevent chaos.

Paris became very tense. The governor of Paris asked both the "Triumvirs" and Condé (the Protestant leader) to leave the city. Condé left on 23 March, and Guise, Montmorency, and Saint-André left on 24 March, heading to Fontainebleau to secure the king and Catherine.

On 27 March, the "Triumvirs" arrived at Fontainebleau with a large cavalry force and brought the king and Catherine to Paris under "their protection." Protestants saw this as making the royal family their prisoners.

Condé then raised the standard of revolt in Orléans on 2 April, starting the French Wars of Religion. Many cities rose up in favor of Condé's cause.

On 4 April 1562, Montmorency returned to Paris and led an armed force to storm Protestant temples, confiscating weapons and burning the buildings. His soldiers patrolled the streets, searching for Protestant preachers.

Condé published a manifesto blaming the "Triumvirate" of Montmorency, Guise, and Saint-André for illegal actions and forming a shadow government. Montmorency's nephew Coligny decided to join Condé's cause, rebuking his uncle for allying with the Lorraines.

First War of Religion

Both sides tried to negotiate, but no lasting peace could be reached. Montmorency proposed appealing to the Pope for money and troops to support Catholic France.

Montmorency and Guise were present at the siege of the Protestant-held city of Rouen. The King of Navarre, who was leading the siege, received a fatal wound. Command then fell to Montmorency.

After the successful siege of Rouen, the royal army, led by Guise and Montmorency, marched to confront Condé's Protestant army. Condé had advanced on Paris but then turned north towards Normandie. Montmorency intercepted the Protestant army at Dreux.

Battle of Dreux and Capture

On 19 December 1562, the royal army engaged the Protestants at the Battle of Dreux. Montmorency commanded the left side of the royal army. During the battle, his forces were attacked, and Montmorency was wounded and captured for the third time in his career. He was taken to Orléans as a prisoner.

In the initial rumors, it was reported that Montmorency had been killed. However, he was alive, though wounded. The battle was a victory for the royalists, especially since Condé was also captured. Montmorency's son was killed in the battle, as was Saint-André. The Duke of Guise intended to continue the war, but he was assassinated during the siege of Orléans. His death opened the way for negotiations.

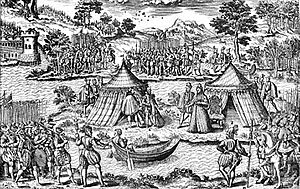

Peace of Amboise

With Montmorency in Protestant captivity and Condé in royal captivity, Queen Catherine initiated negotiations between the two men to end the civil war. They met at the Île aux Bœufs. The result was the Edict of Amboise, published on 19 March 1563. It granted limited Protestant worship, mainly for the nobility, and aimed to bring peace.

As a sign of peace, the royal court entered Orléans. Montmorency, Catherine, and Condé made a solemn entrance. Montmorency and Condé then jointly led a force to recapture Le Havre from the English, who had been supporting the Protestants.

Grand Tour of the Kingdom

In 1564, Queen Catherine decided the court would undertake a grand tour of the kingdom. This was meant to bring noble support back to the king after the civil war and ensure obedience to the Edict of Amboise. Montmorency played a very important role on this tour. It was his duty to maintain discipline in the large moving court, give orders to local governors, and ensure everything was ready for the king's arrival.

During the tour, Montmorency helped place his allies in positions of authority. In January 1565, a confrontation almost broke out in Paris between Montmorency's eldest son (the governor of Paris) and the Cardinal de Lorraine, showing the ongoing rivalry between the two families.

At Bayonne in June 1565, the court met with the Duke of Alba, representing King Philip II of Spain. Montmorency argued in favor of the crown's policy of toleration, saying the alternative was civil war.

At Moulins in January 1566, Catherine tried to reconcile the Montmorency and Lorraine families. Oaths were exchanged, but the reconciliation was not entirely sincere, as Montmorency left in anger when the young Duke of Guise arrived at court.

Montmorency's second son, Damville, was made a Marshal as a reward for his father's loyal service.

Surprise of Meaux and Final Battle

Protestant nobles became suspicious of the peace, especially with changes to the Edict of Amboise and the hiring of Swiss mercenaries by the crown. Condé tried to gain supreme command of the French army but failed. He and Montmorency's nephews, Andelot and Coligny, left court.

They planned a coup attempt similar to the one in Amboise in 1560, gathering cavalry at Meaux to kidnap the royal family. The court was warned and decided to retreat to Paris. Montmorency and the king's Swiss guard held back the Protestant cavalry while the king and Catherine made their way to Paris.

Second War of Religion

With their coup failed, the Protestant leaders decided to besiege the king in Paris. Montmorency organized the royal defense of the capital. He called for reinforcements to build an army strong enough to break the Protestant siege. Negotiations took place, but the religious demands of the Protestants were unacceptable to Montmorency, who did not want a religiously divided kingdom.

The situation in Paris was tense, with food shortages. When a key point in the city's grain supply fell to the Protestants, people blamed Montmorency and his son. Montmorency then took the offensive.

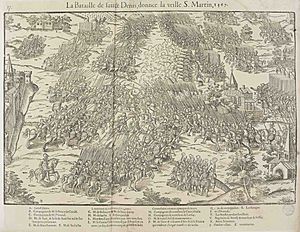

Battle of Saint-Denis and Death

Montmorency engaged the besieging Protestant army outside Paris at the Battle of Saint-Denis on 10 November 1567. He commanded an army of about 25,000 men.

During the battle, Montmorency's forces were attacked, and he became surrounded and wounded. He refused to surrender and was shot. His sons managed to reach him and extract him from the field. He was taken to his Parisian residence, where he died two days later, on 12 November 1567.

Montmorency's eldest son, Marshal Montmorency, then led the royal cavalry, which was inspired by the Constable's wounding. The royal army won the battle, but the Protestant forces managed to retreat.

Anne de Montmorency's funeral was a grand event, almost like a royal funeral. His coffin was buried at the foot of King Henri II's tomb in the Basilica of Saint-Denis. An effigy (a statue of him) was created, showing the wounds he received at Saint-Denis.

Legacy

The office of Constable was not filled after Montmorency's death. The highest military office became lieutenant-general, given to the king's eldest brother, the Duke of Anjou. This was a disappointment to Montmorency's eldest son, who had hoped to become Constable.

Years later, the man who shot Montmorency, Robert Stuart, was captured and killed in cold blood by Montmorency's brother-in-law, seeking revenge.

Reputation

Anne de Montmorency's military reputation was mixed. He lost more battles than he won. However, he was considered a "courageous soldier." People also highly regarded his political skills and prudence. Some historians described his approach to government as "autocratic," meaning he liked to be in charge.

Many people at the time saw him as the first true "favorite" in French history. This meant his power came from his close relationship with the king, rather than just from his family's lands. He was seen as a strong and capable leader who helped many other noble families rise to prominence.

See also

In Spanish: Anne de Montmorency para niños

In Spanish: Anne de Montmorency para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |