Catherine de' Medici facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Catherine de' Medici |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

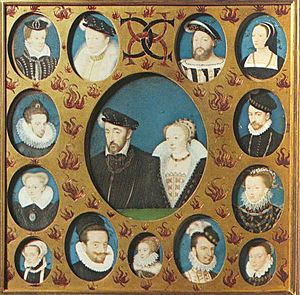

Portrait from the workshop of François Clouet, c. 1560

|

|||||

| Queen consort of France | |||||

| Tenure | 31 March 1547 – 10 July 1559 | ||||

| Coronation | 10 June 1549 | ||||

| Queen regent of France | |||||

| Regency | 5 December 1560 – 17 August 1563 | ||||

| Monarch | Charles IX | ||||

| Born | 13 April 1519 Florence, Republic of Florence |

||||

| Died | 5 January 1589 (aged 69) Château de Blois, Kingdom of France |

||||

| Burial | 4 February 1589 Saint-Sauveur, Blois 4 April 1609 Saint Denis Basilica |

||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue |

|

||||

|

|||||

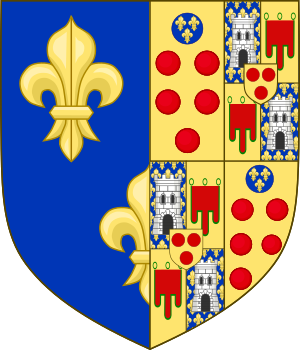

| House | Medici | ||||

| Father | Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino | ||||

| Mother | Madeleine de La Tour d'Auvergne | ||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Catherine de' Medici (born April 13, 1519 – died January 5, 1589) was a noblewoman from Florence, Italy. She belonged to the powerful House of Medici family. Catherine became Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 after marrying King Henry II.

She was also the mother of three French kings: Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III. The time when her sons ruled is often called "the age of Catherine de' Medici". This is because she had a lot of power and influence in France's politics during those years.

Catherine was born in Florence. Her parents were Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, and Madeleine de La Tour d'Auvergne. In 1533, when she was 14, Catherine married Henry. He was the second son of King Francis I of France. Henry became the next in line to the throne when his older brother, Francis, died in 1536. Catherine's marriage was arranged by her uncle, Pope Clement VII.

During his reign, King Henry didn't let Catherine get involved in government. He preferred to listen to his main mistress, Diane de Poitiers. Diane had a lot of influence over him. When Henry died in 1559, Catherine suddenly became very important. Her son, Francis II, was only 15 and not very strong.

When Francis II died in 1560, Catherine became the ruler (regent) for her 10-year-old son, King Charles IX. This gave her a lot of power. After Charles died in 1574, Catherine played a key role in the rule of her third son, Henry III. He stopped listening to her advice only near the end of her life. He died just seven months after her.

Catherine's three sons ruled France during a time of almost constant civil and religious wars. The problems the monarchy faced were very difficult. However, Catherine managed to keep the royal family and the government working, even during these tough times. At first, Catherine tried to make peace and gave some things to the rebelling Protestants, who were known as Huguenots. But she didn't fully understand why they believed what they did. Later, she became frustrated and angry, leading her to use harsh rules against them.

Because of this, she was blamed for the terrible things that happened to Protestants under her sons' rule. This included the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were killed in France. Some historians say Catherine wasn't fully to blame for the worst decisions. But her letters show she could be very tough. Her power was limited by the civil wars. So, her actions might have been desperate ways to keep the House of Valois family on the throne. She also supported the arts to make the monarchy look strong, even though its power was declining. Without Catherine, it's unlikely her sons would have stayed in power. She has been called "the most important woman in Europe" in the 1500s.

Contents

Early Life and Childhood

Catherine de' Medici was born Caterina Maria Romula de' Medici on April 13, 1519, in Florence, Italy. She was the only child of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, and his wife, Madeleine de la Tour d'Auvergne. Her parents had married the year before as part of an agreement between King Francis I of France and Lorenzo's uncle, Pope Leo X.

Sadly, within a month of Catherine's birth, both her parents died. Madeleine died on April 28 from a fever after childbirth. Lorenzo died on May 4. King Francis I wanted Catherine to grow up in the French court. But Pope Leo refused. He wanted her to marry Ippolito de' Medici.

Catherine was first cared for by her grandmother, Alfonsina Orsini. After Alfonsina died in 1520, Catherine lived with her cousins. Her aunt, Clarice de' Medici, raised her. When Pope Leo died in 1521, the Medici family briefly lost power. But then Cardinal Giulio de' Medici was elected Pope Clement VII in 1523.

Clement had Catherine live in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence. The people of Florence called her duchessina, meaning "the little duchess." This was because of her claim to the Duchy of Urbino.

In 1527, the Medici family was overthrown in Florence. Catherine was taken hostage and placed in different convents. Her last home was the Santissima Annuziata delle Murate for three years. Some say these were the happiest years of her life. Pope Clement had to crown Charles of Habsburg as Holy Roman Emperor. This was in exchange for Charles's help to retake Florence. In October 1529, Charles's troops surrounded Florence. The city finally gave up on August 12, 1530. Clement then brought Catherine from her convent to Rome. He greeted her warmly and then began to find her a husband.

Marriage to Henry

When Catherine visited Rome, a Venetian visitor described her. He said she was "small and thin, and without delicate features." He also noted her "protruding eyes," which were common in the Medici family. Still, many noblemen wanted to marry her. James V of Scotland was one of them.

In early 1533, King Francis I of France suggested his second son, Henry, Duke of Orléans, marry Catherine. Pope Clement quickly agreed. Henry was a great match for Catherine. Even though she was wealthy, she was not from a royal family.

The wedding was a very grand event. It had many fancy displays and gifts. It took place in Marseille on October 28, 1533.

Catherine did not see much of her husband in their first year of marriage. But the ladies of the court liked her. They were impressed by her intelligence and her eagerness to please. However, Catherine's standing at the French court changed when her uncle Clement died on September 25, 1534. The next pope, Paul III, did not feel he had to keep Clement's promises. He ended the alliance with France and stopped paying Catherine's large dowry.

Prince Henry showed no interest in Catherine as a wife. Instead, he openly had other women as his mistresses. For the first ten years of their marriage, they did not have any children. In 1537, Henry had a short affair with Filippa Duci. She gave birth to a daughter, whom he publicly recognized. This showed that Henry could have children. This put more pressure on Catherine to have a child.

Becoming Dauphine

In 1536, Henry's older brother, Francis, became sick after playing tennis. He died soon after. This made Henry the next in line to the throne.

As the dauphine (the wife of the heir), Catherine was expected to have a child who would become the next king. Many people suggested that the king and Henry should divorce Catherine because she had not had children. But on January 19, 1544, she finally gave birth to a son, named Francis.

After having one child, Catherine had no trouble getting pregnant again. On April 2, 1545, she had a daughter, Elisabeth. She went on to have eight more children with Henry. Seven of them lived past infancy. These included the future Charles IX (born 1550) and Henry III (born 1551). The future of the House of Valois family, which had ruled France since the 1300s, seemed secure.

However, having children did not make Catherine's marriage better. Around 1538, when Henry was 19, he started a relationship with Diane de Poitiers, who was 38. He loved her for the rest of his life. Even so, he respected Catherine's position as his wife. When King Francis I died on March 31, 1547, Catherine became the Queen of France. She was crowned on June 10, 1549.

Queen of France

As queen, Henry gave Catherine almost no political power. She sometimes acted as ruler when he was away, but her power was only on paper. Henry gave the Château de Chenonceau, which Catherine wanted, to Diane de Poitiers. Diane became very powerful, giving out favors and gifts. Diane never saw Catherine as a threat. She even encouraged Henry to spend more time with Catherine and have more children.

In 1556, Catherine almost died giving birth to twin daughters, Jeanne and Victoire. Jeanne was stillborn. Victoire died seven weeks later. Because this birth was so dangerous, the king's doctor advised Henry not to have any more children with Catherine.

Henry's reign also saw the rise of the Guise brothers: Charles and Francis. Their sister, Mary of Guise, had married James V of Scotland and was the mother of Mary, Queen of Scots. Mary, Queen of Scots, came to the French court at age five. She was promised to Henry's son, Francis. Catherine raised her with her own children.

On April 3-4, 1559, Henry signed a peace treaty with the Holy Roman Empire and England. This ended a long period of wars. The treaty was sealed by the marriage of Catherine's 13-year-old daughter, Elisabeth, to Philip II of Spain. Their wedding was celebrated with many parties, dances, and jousting for five days.

King Henry took part in the jousting. He wore Diane's black and white colors. He defeated two dukes. But then a young count, Gabriel, comte de Montgomery, hit him hard. Henry insisted on jousting Montgomery again. This time, Montgomery's lance broke in the king's face. Henry fell, bleeding, with splinters in his eye and head. Catherine, Diane, and Prince Francis all fainted.

Henry was taken to the Château de Tournelles. Doctors removed five splinters from his head. One had gone into his eye and brain. Catherine stayed by his side. Diane stayed away, fearing the Queen would send her away. For ten days, Henry's condition changed. Sometimes he felt well enough to write letters. But slowly, he lost his sight, speech, and ability to think. On July 10, 1559, he died at age 40. From that day, Catherine wore black clothes to mourn Henry. She chose a broken lance as her symbol, with the words "from this come my tears and my pain."

Queen Mother

Francis II's Rule

Francis II became king at 15 years old. The day after Henry II's death, the Cardinal of Lorraine and the Duke of Guise quickly took power. Their niece, Mary, Queen of Scots, had married Francis II the year before. They moved into the Louvre Palace with the young king and queen. The English ambassador reported that "the house of Guise ruleth and doth all about the French king."

For a while, Catherine worked with the Guises because she had to. She wasn't officially supposed to have a role in Francis's government, as he was old enough to rule. But all his official papers began with words like: "This being the good pleasure of the Queen, my lady-mother, and I also approving of every opinion that she holdeth, am content and command that...". Catherine used her new power. One of her first actions was to make Diane de Poitiers give back the crown jewels and the Château de Chenonceau.

The Guise brothers began to persecute Protestants with great enthusiasm. Catherine took a more moderate approach. She spoke against the Guise persecutions, even though she didn't agree with the Huguenots' beliefs. Protestants looked to Antoine de Bourbon, a prince, for leadership. Then they turned to his brother, Louis de Bourbon, who planned to overthrow the Guises by force. When the Guises found out, they moved the court to the fortified Château d'Amboise. The Duke of Guise attacked the rebels in the woods around the château. Many rebels were killed, including their leader.

In June 1560, Michel de l'Hôpital became the Chancellor of France. He worked with Catherine to uphold the law as the country became more chaotic. They believed that Protestants who worshipped privately and didn't fight should not be punished. On August 20, 1560, Catherine and the chancellor presented this idea to a meeting at Fontainebleau. Historians see this as an early example of Catherine's skill in ruling.

Meanwhile, Condé gathered an army and began attacking towns in the south. Catherine ordered him to court and had him imprisoned. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. But his life was saved when the king became ill and died from an infection in his ear.

When Catherine realized Francis was dying, she made a deal with Antoine de Bourbon. He would give up his right to rule for the next king, Charles IX. In return, his brother Condé would be freed. So, when Francis died on December 5, 1560, the Privy Council named Catherine as the governor of France. She had a lot of power. She wrote to her daughter Elisabeth: "My main goal is to honor God in all things and to keep my power, not for myself, but to save this kingdom and for the good of all your brothers."

Charles IX's Rule

Charles IX was nine years old when he was crowned. He even cried during the ceremony. At first, Catherine kept him very close. She even slept in his room. She led his council, made decisions, and managed government affairs. However, she could not control the whole country. It was on the edge of civil war. In many parts of France, nobles ruled instead of the king. The challenges Catherine faced were complex and hard for her to understand as a foreigner.

She called church leaders from both sides to try and solve their religious differences. Despite her hopes, the meeting ended in failure on October 13, 1561. Catherine failed because she saw the religious divide only as a political problem. She thought everything would be fine if the leaders just agreed. In January 1562, Catherine issued the Edict of Saint-Germain. This law was more tolerant of Protestants. It was another attempt to build bridges with them.

However, on March 1, 1562, the Duke of Guise and his men attacked worshipping Huguenots in a barn. This event, known as the Massacre of Vassy, killed 74 people and wounded 104. Guise called it "a regrettable accident." He was cheered as a hero in Paris. But the Huguenots demanded revenge. The massacre started the French Wars of Religion. For the next 30 years, France was either in civil war or an uneasy peace.

Within a month, Louis de Bourbon and Admiral Gaspard de Coligny had gathered an army. They allied with England and took many towns in France. Catherine met Coligny, but he refused to back down. She told him: "Since you rely on your forces, we will show you ours." The royal army quickly fought back and surrounded the Huguenot-held city of Rouen.

Catherine visited the dying Antoine de Bourbon, who was fatally wounded. Catherine insisted on visiting the battlefield herself. When warned of the dangers, she laughed, "My courage is as great as yours." The Catholics took Rouen. But their victory was short-lived. On February 18, 1563, a spy shot the Duke of Guise at the siege of Orléans. This murder started a noble feud that complicated the French civil wars for years. Catherine, however, was happy about her ally's death. She told the Venetian ambassador, "If Monsieur de Guise had perished sooner, peace would have been achieved more quickly." On March 19, 1563, the Edict of Amboise ended the war. Catherine then brought together Huguenot and Catholic forces to take back Le Havre from the English.

Dealing with Huguenots

On August 17, 1563, Charles IX was declared old enough to rule. But he was never able to rule on his own and didn't seem interested in government. Catherine decided to make sure the Edict of Amboise was followed. She also wanted to bring back loyalty to the king. To do this, she traveled with Charles and the court around France. This trip lasted from January 1564 to May 1565.

Catherine talked with Jeanne d'Albret, the Protestant queen of Navarre. She also met her daughter Elisabeth near the Spanish border. Philip II of Spain sent the Duke of Alba to tell Catherine to get rid of the Edict of Amboise. He wanted her to find ways to punish those who didn't follow the Catholic faith.

In 1566, Charles and Catherine suggested a plan to the Ottoman Empire. They wanted to move French Huguenots and German Protestants to Ottoman-controlled Moldavia. This would create a military colony and a barrier against the House of Habsburg. This plan also had the benefit of removing Huguenots from France. But the Ottomans were not interested.

On September 27, 1567, Huguenot forces tried to ambush the king. This event, known as the Surprise of Meaux, started a new civil war. The court fled to Paris in a hurry. The war ended with the Peace of Longjumeau in March 1568. But fighting and unrest continued. The Surprise of Meaux changed Catherine's policy towards the Huguenots. From then on, she stopped trying to compromise. She adopted a policy of harsh control. She told the Venetian ambassador in June 1568 that Huguenots could only be expected to deceive. She praised the Duke of Alba's harsh rule in the Netherlands, where thousands of Protestants were killed.

The Huguenots went to the fortified city of La Rochelle on the west coast. Jeanne d'Albret and her 15-year-old son, Henry of Bourbon, joined them. Jeanne wrote to Catherine: "We have decided to die, all of us, rather than abandon our God, and our religion." Catherine called Jeanne "the most shameless woman in the world." Still, the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, signed on August 8, 1570, gave Huguenots more tolerance than ever before. This was because the royal army ran out of money.

Catherine wanted to strengthen the Valois family through important marriages. In 1570, Charles IX married Elisabeth of Austria, the daughter of an emperor. Catherine also wanted one of her two youngest sons to marry Elizabeth I of England. After her daughter Elisabeth died in 1568, Catherine suggested her youngest daughter Margaret marry Philip II of Spain. Now she wanted Margaret to marry Henry III of Navarre, Jeanne's son. This would unite the Valois and Bourbon families.

However, Margaret was secretly involved with Henry of Guise. When Catherine found out, she had her daughter brought from her bed. Catherine and the king then beat her, tearing her nightclothes and pulling out her hair.

Catherine pressured Jeanne d'Albret to come to court. She wrote that she wanted to see Jeanne's children and promised not to harm them. Jeanne replied: "Pardon me if, reading that, I want to laugh, because you want to relieve me of a fear that I've never had. I've never thought that, as they say, you eat little children." When Jeanne did come to court, Catherine pushed her hard. Jeanne finally agreed to the marriage between her son and Margaret. Henry could remain a Huguenot. When Jeanne arrived in Paris to buy wedding clothes, she became ill and died on June 9, 1572, at age 43. The wedding took place on August 18, 1572, in Notre-Dame, Paris.

St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre

Three days later, Admiral Coligny was walking back to his rooms when he was shot. He was wounded in the hand and arm. A smoking gun was found in a window, but the shooter had escaped. Coligny was taken to his home, where a surgeon removed a bullet and cut off a damaged finger. Catherine, who reportedly showed no emotion at first, later visited Coligny and promised to punish his attacker. Many historians blame Catherine for the attack on Coligny. Others point to the Guise family or a Spanish plot to end Coligny's influence on the king. Whatever the truth, the terrible killings that followed quickly went out of control.

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, which began two days later, has damaged Catherine's reputation ever since. There is reason to believe she was part of the decision. On August 23, Charles IX is said to have ordered, "Then kill them all! Kill them all!" Historians suggest that Catherine and her advisors expected a Huguenot uprising to get revenge for the attack on Coligny. So, they chose to strike first and kill the Huguenot leaders while they were still in Paris after the wedding.

The killing in Paris lasted for almost a week. It spread to many parts of France and continued into the autumn. One historian called it "not a day, but a season." On September 29, when Navarre became a Roman Catholic to avoid being killed, Catherine laughed. From this time comes the story of the wicked Italian queen. Huguenot writers called Catherine a scheming Italian who used harsh methods to kill all her enemies at once.

Henry III's Rule

Two years later, Catherine faced a new crisis when Charles IX died at age 23. His last words were "oh, my mother..." The day before he died, he named Catherine as regent. This was because his brother and heir, Henry, Duke of Anjou, was in Poland, where he had been elected king the year before. However, three months after his coronation in Poland, Henry left that throne and returned to France to become King of France. Catherine wrote to Henry about Charles IX's death: "I am heartbroken to have seen such a scene and the love he showed me at the end... My only comfort is to see you here soon, as your kingdom needs, and in good health. If I were to lose you, I would have myself buried alive with you."

Henry was Catherine's favorite son. Unlike his brothers, he became king as an adult. He was also healthier, though he had weak lungs and was often tired. However, his interest in government tasks was inconsistent. He relied on Catherine and her team of secretaries until the last few weeks of her life. He often avoided state affairs, focusing instead on religious acts, like pilgrimages and self-punishment.

Henry married Louise de Lorraine-Vaudémont in February 1575, two days after his coronation. His choice ruined Catherine's plans for a political marriage to a foreign princess. Rumors that Henry could not have children were common. A papal visitor noted, "it is only with difficulty that we can imagine there will be offspring... doctors and those who know him well say that he has an extremely weak body and will not live long."

As time passed and it seemed less likely that Henry would have children, Catherine's youngest son, Francis, Duke of Alençon, played on his role as heir to the throne. He often used the chaos of the civil wars, which were now also about noble power struggles, to his advantage. Catherine did everything she could to bring Francis back in line. Once, in March 1578, she lectured him for six hours about his dangerous behavior.

In 1576, Francis allied with the Protestant princes against the king. This put Henry's throne in danger. On May 6, 1576, Catherine agreed to almost all Huguenot demands in the Edict of Beaulieu. This treaty became known as the Peace of Monsieur because people thought Francis had forced it on the king. Francis died of a lung disease in June 1584. This happened after a terrible military action where his army was defeated. Catherine wrote the next day: "I am so sad to live long enough to see so many people die before me. I know that God's will must be obeyed, that He owns everything, and that He lends us children only for as long as He likes." The death of her youngest son was a disaster for Catherine's plans for her family. By law, only males could become king. So, the Protestant Henry of Navarre now became the next in line to the French throne.

Catherine had at least taken the step of marrying Margaret, her youngest daughter, to Navarre. However, Margaret became almost as much of a problem for Catherine as Francis. In 1582, she returned to the French court without her husband. Catherine was heard yelling at her for having lovers. Catherine sent a messenger to Navarre to arrange Margaret's return. In 1585, Margaret fled Navarre again. She went to her property and begged her mother for money. Catherine sent her only enough "to put food on her table." Moving to a fortress, Margaret took a new lover. Catherine asked Henry to act before Margaret brought shame on them again. In October 1586, Henry had Margaret locked up in the Château d'Usson. Her lover was executed. Catherine removed Margaret from her will and never saw her again.

Catherine could not control Henry in the same way she had controlled Francis and Charles. Her role in his government became that of a chief manager and traveling diplomat. She traveled widely across the kingdom, enforcing his authority and trying to prevent war. In 1578, she took on the task of bringing peace to the south. At 59 years old, she began an 18-month journey around southern France to meet Huguenot leaders face to face. Her efforts earned Catherine new respect from the French people. When she returned to Paris in 1579, she was greeted by crowds. A Venetian visitor wrote: "She is an tireless princess, born to control a people as unruly as the French. They now recognize her good qualities, her concern for unity, and are sorry not to have appreciated her sooner." However, she had no illusions. On November 25, 1579, she wrote to the king, "You are on the eve of a general revolt. Anyone who tells you differently is a liar."

Catholic League

Many leading Roman Catholics were shocked by Catherine's attempts to make peace with the Huguenots. After the Edict of Beaulieu, they started forming local groups to protect their religion. The death of the heir to the throne in 1584 led the Duke of Guise to become the leader of the Catholic League. He planned to stop Henry of Navarre from becoming king. Instead, he wanted to put Henry's Catholic uncle, Cardinal Charles de Bourbon, on the throne. To do this, he gathered powerful Catholic princes and nobles. He signed a treaty with Spain and prepared for war against the Protestants. By 1585, Henry III had no choice but to go to war against the League. As Catherine said, "peace is carried on a stick." She wrote to the king, "Take care, especially about your person. There is so much betrayal about that I die of fear."

Henry could not fight both the Catholics and the Protestants at once. Both groups had stronger armies than his own. In the Treaty of Nemours, signed on July 7, 1585, he was forced to agree to all the League's demands. He even had to pay their troops. He went into hiding to fast and pray, surrounded by a bodyguard known as "the Forty-five." He left Catherine to sort out the problems. The monarchy had lost control of the country. It was not able to help England against the coming Spanish attack. The Spanish ambassador told Philip II that the problem was about to explode.

By 1587, the Catholic reaction against Protestants had become a movement across Europe. Elizabeth I of England's execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, on February 8, 1587, angered the Catholic world. Philip II of Spain prepared to invade England. The League took control of much of northern France to secure French ports for his armada.

Last Months and Death

Henry hired Swiss troops to help him defend himself in Paris. However, the people of Paris claimed the right to defend the city themselves. On May 12, 1588, they set up barricades in the streets. They refused to take orders from anyone except the Duke of Guise. When Catherine tried to go to Mass, her way was blocked. But she was allowed through the barricades. A writer reported that she cried during her lunch that day. She wrote, "Never have I seen myself in such trouble or with so little light by which to escape." As usual, Catherine advised the king, who had fled the city just in time, to make a deal and live to fight another day. On June 15, 1588, Henry signed an agreement that gave in to all the League's latest demands.

On September 8, 1588, at Blois, where the court had gathered, Henry suddenly fired all his ministers. Catherine, who was in bed with a lung infection, had not been told. The king's actions effectively ended her time in power.

On January 5, 1589, Catherine died at age 69, likely from a lung disease. A writer noted: "those close to her believed that her life had been shortened by displeasure over her son's deed."

Because Paris was controlled by enemies of the king, Catherine had to be buried temporarily at Blois. Years later, Diane, Henry II's daughter, had Catherine's remains moved to the Basilica of Saint-Denis in Paris. In 1793, during the French Revolution, a mob threw her bones into a mass grave with those of other kings and queens.

Supporter of the Arts

Catherine believed in the idea of a learned ruler who was strong in both knowledge and war. She was inspired by her father-in-law, King Francis I, who had hosted Europe's best artists. She was also inspired by her Medici ancestors. During a time of civil war and declining respect for the monarchy, she tried to boost royal prestige through grand cultural displays. Once she controlled the royal money, she started supporting the arts for 30 years. During this time, she oversaw a unique late French Renaissance culture in all areas of the arts.

A list of items found at Catherine's home after her death shows she was a keen collector. It included tapestries, hand-drawn maps, sculptures, rich fabrics, ebony furniture with ivory, sets of china, and pottery. There were also hundreds of portraits, which were very popular during her life. Many portraits in her collection were by Jean Clouet and his son François Clouet. François Clouet drew and painted portraits of all Catherine's family and many court members. After Catherine's death, the quality of French portraiture declined.

Beyond portraits, little is known about painting at Catherine de' Medici's court. In the last two decades of her life, two painters stand out: Jean Cousin the Younger and Antoine Caron. Caron became Catherine's official painter. Caron's vivid style, with its love of ceremonies and focus on massacres, shows the tense atmosphere of the French court during the Wars of Religion.

Many of Caron's paintings, like those of the Triumphs of the Seasons, are allegorical. They reflect the festivities for which Catherine's court was famous. His designs for the Valois Tapestries celebrate the parties, picnics, and mock battles of the "magnificent" entertainments Catherine hosted. They show events held at Fontainebleau in 1564, at Bayonne in 1565, and at the Tuileries in 1573.

The musical shows especially allowed Catherine to express her creative talents. They were usually about the idea of peace and based on mythological stories. To create the necessary plays, music, and scenery, Catherine hired the best artists and architects of her time. One historian called her "a great creative artist in festivals." Catherine slowly changed traditional entertainments. For example, she made dance more important in the shows. A new art form, the ballet de cour, grew from these changes. Because it combined dance, music, poetry, and setting, the Ballet Comique de la Reine in 1581 is seen as the first true ballet.

Catherine de' Medici's great love among the arts was architecture. As a Medici, she was driven by a passion to build and a desire to leave great achievements behind. After Henry II's death, Catherine wanted to honor her husband's memory. She also wanted to make the Valois monarchy look grander through costly building projects. These included work on the Château de Montceaux, Château de Saint-Maur, and Chenonceau. Catherine built two new palaces in Paris: the Tuileries and the Hôtel de la Reine. She was deeply involved in planning and supervising all her building projects.

Catherine had symbols of her love and sadness carved into her buildings. Poets praised her as the new Artemisia, after a queen who built a famous tomb for her husband. As the main part of a new chapel, she ordered a magnificent tomb for Henry at the basilica of Saint Denis. It was designed by Francesco Primaticcio, with sculptures by Germain Pilon. One art historian called this monument "the last and most brilliant of the royal tombs of the Renaissance." Catherine also asked Germain Pilon to carve a marble sculpture that holds Henry II's heart. A poem on its base says not to wonder that such a small vase can hold such a large heart, because Henry's real heart is in Catherine's chest.

Although Catherine spent huge amounts of money on the arts, most of her support did not leave a permanent legacy. The end of the Valois family soon after her death brought a change in priorities.

Culinary Legend

The story that Catherine de' Medici brought many foods, cooking methods, and utensils from Italy to France is not true. Food historians have shown that these claims are incorrect. They point out that Catherine's father-in-law, King Francis I, and other French nobles had already eaten at Italy's best tables during the king's wars there. Also, a large Italian group visited France for Catherine's father's wedding to her French mother. Catherine also had little influence at court until her husband died.

In fact, many Italians—bankers, silk-weavers, philosophers, musicians, and artists, including Leonardo da Vinci—had already moved to France. They helped the growing Renaissance movement. Still, popular culture often credits Catherine with bringing Italian cooking and forks to France.

The earliest known mention of Catherine as popularizing Italian cooking is from an encyclopedia published in 1754. It described fancy French cooking as coming from "that crowd of corrupt Italians who served at the court of Catherine de' Medici."

Children

Catherine de' Medici married Henry, Duke of Orléans, who would become Henry II of France, in Marseille on October 28, 1533. She gave birth to ten children. Four sons and three daughters lived to adulthood and married. Three of her sons became kings of France. Two of her daughters married kings, and one married a duke. Catherine outlived all her children except Henry III, who died seven months after her, and Margaret. Victoire and Jeanne were twin daughters born in 1556; Jeanne was stillborn; Victoire died less than two months later.

- Francis II, King of France (January 19, 1544 – December 5, 1560). Married Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1558.

- Elisabeth (April 2, 1545 – October 3, 1568). Married Philip II, King of Spain, in 1559.

- Claude (November 12, 1547 – February 21, 1575). Married Charles III, Duke of Lorraine, in 1559.

- Louis, Duke of Orléans (February 3, 1549 – October 24, 1550). Died as a baby.

- Charles IX, King of France (June 27, 1550 – May 30, 1574). Married Elizabeth of Austria in 1570.

- Henry III, King of France (September 19, 1551 – August 2, 1589). Married Louise of Lorraine in 1575.

- Margaret (May 14, 1553 – March 27, 1615). Married Henry, King of Navarre, who later became Henry IV of France, in 1572.

- Hercules, Duke of Anjou (March 18, 1555 – June 19, 1584). Renamed Francis when he was confirmed.

- Victoire (June 24, 1556 – August 17, 1556). Died as a baby.

- Jeanne (June 24, 1556). Stillborn.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Catalina de Médici para niños

In Spanish: Catalina de Médici para niños