Gaspard II de Coligny facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Gaspard II de Coligny |

|

|---|---|

| Seigneur de Châtillon | |

|

|

| Portrait by François Clouet, between 1565 and 1570 | |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Issue | |

|

|

| Nobility | Coligny |

| Father | Gaspard I de Coligny |

| Mother | Louise de Montmorency |

| Born | 16 February 1519 Châtillon-sur-Loing, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 24 August 1572 (aged 53) Paris, Kingdom of France |

Gaspard de Coligny, also known as the Lord of Châtillon, was an important French nobleman. He was born on February 16, 1519, and died on August 24, 1572. He held the title of Admiral of France and was a key leader of the Huguenots (French Protestants) during the French Wars of Religion.

Coligny served under King Francis I and King Henry II during the Italian Wars. He became very well-known for his military skills and because his uncle, Anne de Montmorency, was a favorite of the king. When Francis II became king, Coligny converted to Protestantism. He then became a major supporter of the Reformation among the nobles during the early reign of Charles IX.

When civil war broke out in 1562, Coligny joined the Huguenots. He fought alongside Louis, Prince of Condé in the first two civil wars. After Condé's death in the third civil war, Coligny became the main military leader of the Huguenots. In 1563, the powerful Guise family accused him of being responsible for the assassination of the Catholic leader Francis, Duke of Guise. Coligny was assassinated in 1572, at the start of the St Bartholomew's Day massacre, on the orders of Henry, Duke of Guise.

Contents

Coligny's Family and Early Life

Gaspard de Coligny came from a noble family in Burgundy, France. His family had been serving the King of France since the 11th century. Gaspard's father, Gaspard I de Coligny, was a military leader known as the 'Marshal of Châtillon'. He fought in the Italian Wars and became a Marshal of France in 1516.

Gaspard's mother was Louise de Montmorency, who was the sister of Anne de Montmorency, a future important official called the Constable. Gaspard had two brothers, Odet and François. All three brothers played important roles in the early French Wars of Religion.

Gaspard was born in Châtillon-sur-Loing in 1519. His father died in 1522, so Gaspard was raised by his mother, Louise, and his uncle, Anne de Montmorency. Louise made sure he received a good education. He studied classic subjects like those taught by Cicero and Ptolemy. Both his mother and his teacher, Nicolas Bérauld, were humanists. They were friends with Protestant thinkers, which influenced Coligny as he grew up.

Military Career under Francis I and Henri II

Coligny showed his bravery in military campaigns. In 1543, he was wounded during sieges at Montmédy and Bains. In 1544, he fought in Italy under the Count of Enghien. He commanded a regiment and was knighted after the Battle of Ceresole. He also took part in other military actions, including an expedition to England in 1545.

Rising Through the Ranks

When Henri II became king, Coligny's uncle, Montmorency, regained his influence. Coligny quickly benefited from this. He was made colonel-general of the infantry, a very important military position. He was a skilled military reformer, and the king approved his rules for keeping the infantry disciplined in 1551. Soon after, he became a Knight of the Order of St. Michel. In the same year, he married Charlotte de Laval.

Coligny became close friends with other important court figures like Francis, Duke of Guise and Piero Strozzi. He continued to gain important roles because of his uncle's close relationship with the king. In 1549, he became a leader in the Boulonnais region, and then in Boulogne-sur-Mer a year later. In 1551, he was made Governor of Paris, a highly desired position.

A year later, he became the Admiral of France, taking over from Claude d'Annebaut. This title was mostly about prestige, not just naval matters. It was the second most important title after his uncle's position as Constable.

Battles and Rivalries

When war started again in 1552, Coligny, as Colonel-General of the infantry, played a key role in the French victory at the Battle of Renty. He fought under the command of Guise. After the battle, Coligny and Guise argued over who deserved credit for the victory. Their friendship was damaged, even though the king made them make peace.

In 1555, Coligny was given a second governorship, for the important border region of Picardy. This replaced Antoine of Navarre, which made Navarre very unhappy.

Coligny also tried to establish a French colony called France Antarctique in Rio de Janeiro in 1555. His friend, Vice-Admiral Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon, led this effort. However, the Portuguese later expelled them in 1567.

In 1557, Coligny was in charge of defending Saint-Quentin when it was attacked by a Spanish army. The French relief army, led by Montmorency, was badly defeated at the Battle of Saint-Quentin. Coligny had promised the king he could hold the town for eight weeks. However, the Spanish broke through the town's defenses nine days later, and Coligny was captured. He was held prisoner for two years and became ill due to the harsh conditions. He was released after paying a large ransom.

Coligny Becomes a Calvinist

During this time, Protestantism was gaining followers among French nobles. Coligny's brother, Andelot, became a Protestant in 1556. In 1558, while Coligny was imprisoned, Andelot sent him a Protestant book to comfort him. The exact time Coligny converted to Calvinism is not clear, but by September 1558, he had received a letter about his faith from John Calvin. By 1559, people at court suspected Coligny's religious beliefs because he was not attending Catholic Mass. However, he kept his new faith quiet for a while.

Under King Francis II

After King Henri II died suddenly, Coligny attended a meeting to discuss the new government. He was on good terms with the Guise family and did not join the Conspiracy of Amboise, a plot against them. In January 1560, he resigned his governorship of Picardy because his requests for money to fortify towns were denied.

Speaking for Protestants

Coligny was among those who pushed for an Assembly of Notables in late 1560 to discuss new policies for the country. At this assembly, Coligny clashed with François de Guise. Coligny suggested that Protestants and Catholics should be allowed to live together peacefully, at least for a while. He presented a petition with 50,000 signatures supporting this idea. Guise disagreed, saying religious matters should be left to religious leaders.

Although Coligny did not win over the assembly completely, he became known as the most powerful leader of the Protestant reform party. He also argued for an Estates General, a meeting where representatives from different parts of society could advise the king.

In November 1560, King Francis II became very ill and died on December 5. With his death, the Guise family lost their strong hold on the government. Coligny was happy about this change. Soon after the king's death, Coligny and the Duke of Guise had a heated argument about an uprising in Brittany. Guise was so angry that he said he would have stabbed Coligny if they weren't in court.

Under King Charles IX

Growing Influence

The situation at court changed greatly with Charles IX as the new king. Montmorency returned to power, and the Guise family's influence decreased. Coligny became a central figure for Protestants hoping for a new government. He presented a new petition to Catherine de' Medici, the Queen Mother, asking for Protestants to be allowed to hold services in private homes. This request was denied.

Coligny became more open about his Protestant faith. In February 1561, his son was baptized in the Protestant way. He also hired a Protestant minister for his household. As he became more openly Protestant, his political standing also rose. In March 1561, he was recommended to oversee the young king's education. He was also admitted to the Conseil des Affairs, where royal policy was made.

Tensions and Toleration

On April 1, 1561, Coligny hosted a large Protestant service at his home, inviting many nobles. This angered Montmorency and Guise, who complained to Catherine. Both Catherine and Montmorency criticized Coligny for this bold move. A few days later, Montmorency and Guise were further upset when they learned a Protestant preacher would give a sermon on Easter Sunday. They left to hear a Catholic friar instead. This event led to a temporary reconciliation between the two rivals. Montmorency warned Coligny not to repeat the Palm Sunday event.

Coligny's support for Catherine's regency led to the Edict of Saint-Germain in January 1562. This important edict temporarily made public Protestant worship legal under certain conditions across France. This was the result of what Coligny had been pushing for throughout 1561. In early 1562, Coligny also supported another colonial project, the Fort Caroline colony in Spanish Florida, led by Jean Ribault. This venture also failed.

Road to Civil War

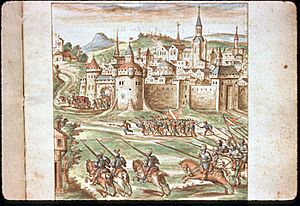

The Edict of Saint-Germain was the final straw for Antoine of Navarre, who broke with the regency and urged Guise to return to form a united front against Catherine's policy. Coligny, sensing the growing hostility, left court on February 22. On his way back to Paris, the Duke of Guise's men were responsible for a massacre at the town of Wassy.

When Guise arrived in Paris, he was welcomed as a hero. Condé, outnumbered in the city, left on March 23. He went to Orléans, where he started a rebellion on April 2, accusing the king of being held captive. Coligny had joined Condé's forces several days earlier. He wrote to Catherine, defending his actions and saying his men were armed because of 'Guise's designs against him.'

The French Wars of Religion

First War (1562-1563)

Many cities across France joined Condé's cause. Coligny defended his support for the rebellion in letters to Catherine and his uncle Montmorency. He criticized Montmorency for allying with the Guise family, who were his family's enemies.

The royal army began to attack. Condé and Coligny negotiated the Treaty of Hampton Court (1562) with Queen Elizabeth of England, offering Le Havre in return for military support. Coligny's brother, Andelot, raised an army of mercenaries in Germany. He successfully brought them into France and joined Condé and Coligny in Orléans.

The royal army captured Rouen after a long siege. The king's commander, Navarre, was wounded and died. Condé wanted to march on Paris, but Coligny suggested going to Normandy to reclaim lost towns and get money from England. Condé decided to march south. The royal army followed, leading to the Battle of Dreux.

The Battle of Dreux was very bloody. Both Condé and Montmorency were captured. Guise led the royal forces to victory, but Coligny skillfully led the Huguenot cavalry to retreat safely back to Orléans. Coligny then marched north to reclaim towns in Normandy. Soon after, peace was declared with the Edict of Amboise.

The Long Peace (1563-1567)

During the siege of Orléans, Francis, Duke of Guise was fatally wounded by a Protestant assassin named Poltrot de Méré. Under questioning, Poltrot sometimes said Coligny was involved. Coligny, who was in Normandy, demanded to question Poltrot to prove his innocence, but Poltrot was quickly executed.

The Guise family was furious and demanded revenge. They launched a lawsuit against Coligny. The king's council eventually took over the case and suspended judgment until the king was older. In January 1564, the king further delayed the judgment for three years, which was a blow to the Guise family. In 1566, the king forced Lorraine (from the Guise family) and Coligny to make peace. An edict on January 29, 1566, declared Coligny innocent.

Coligny was not happy with the Edict of Amboise because he felt it didn't give the Huguenots enough advantages. He focused on international projects, like the Florida colony and trade in the North Sea, but these didn't achieve much. He started to appear at court more often from 1566.

Second War (1567-1568)

Tensions grew again in 1567. Huguenots heard rumors that Spain and France were plotting against them. When the crown hired Swiss soldiers, Protestants feared these troops would be used against them. Coligny, after much debate, joined Condé and other Protestant nobles in a plan to seize the king at Meaux and kill Lorraine.

The plan leaked, and the court quickly fled to Paris. Condé and Coligny pursued them but couldn't break through the Swiss guard. The king was safe in Paris, but very angry.

Condé decided to try and starve Paris into submission. The rebels captured strategic points around the city. Condé demanded the repeal of taxes and free exercise of religion. The crown refused and began gathering forces. Coligny and others were sent to intercept enemy recruits, but they failed.

At the Battle of Saint Denis, Coligny commanded the right flank of Condé's army. The battle was fierce. Condé was unhorsed, and Montmorency was shot. The Swiss troops won the battle for the crown. Condé's forces were smaller, so he withdrew.

The crown followed, hoping the rebel army would fall apart. However, Condé and Coligny kept their army together and united with German mercenaries. Condé then decided to besiege Chartres. Before the siege ended, both sides agreed to a truce and then a formal peace with the Peace of Longjumeau.

Short Peace (1568)

Coligny, Andelot, and Charles de Téligny were the main negotiators for the rebels at Longjumeau. The peace terms were similar to the previous edict, but meant to be permanent. Many Catholics were angry about the peace, leading to riots. In the south, both sides continued to fight.

Coligny was frustrated because he felt the crown was not following the peace agreement. He wrote to Catherine in June, complaining about violations and even assassination plots against him. Catherine dismissed his concerns. In July, masked men shot the lieutenant of Andelot's company. Coligny wrote to the king, suspecting that Catholic groups were behind the attack.

The mood at court changed. The Queen Mother, Catherine, began to be influenced by new advisors. When the Pope offered financial help in return for a war against heresy, the decision was made to overturn the peace. In early September, leading Huguenot nobles, including Coligny, were warned of a plot to arrest them. Coligny, Condé, and others quickly fled south to the Protestant stronghold of La Rochelle. The crown then issued the Edict of Saint-Maur, outlawing Protestantism.

Third War (1568-1570)

Condé and Coligny decided on a new strategy, operating from the Huguenot strongholds in the south. In early 1569, the royal army caught their rear-guard. Condé was captured and then executed. This was a major blow, but Coligny managed to keep the rest of the army together and retreat safely. Although the young Navarre and Condé became the official leaders, Coligny was the true military commander due to their young age. In May 1569, Coligny's brother Andelot died of an illness during the campaign.

Coligny's forces joined with his German allies and defeated a smaller royal army at the Battle of La Roche-l'Abeille. With renewed confidence, Coligny besieged Poitiers. Despite heavy attacks, the garrison held out, and Coligny lifted the siege on September 7. On September 12, the Parliament of Paris declared Coligny a traitor and offered a large reward for his capture.

Soon after, the rebels suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Moncontour. Coligny was shot in the face but survived, though he had to leave the battlefield. The loss of their leader confused the army. However, most of the cavalry escaped. Coligny regrouped his remaining forces and began a long march towards Paris. He sacked the Abbey of Cluny and avoided the royal army. This march eventually led to peace being declared on favorable terms.

Peace and the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre

Negotiations for peace had been ongoing since December 1569. It was agreed that Protestantism would be tolerated, and the Huguenots would receive several towns as security for two years. Coligny had a significant influence on these terms. The bounty on his head was removed, and he was restored to his office as Admiral, with all his property returned.

Leading to the Massacre

In 1571, Coligny married Jacqueline de Montbel d'Entremont. For much of 1570 and 1571, he was careful about returning to court, not fully trusting the king's offers of safety. He stayed in La Rochelle. He was eventually persuaded to return in September 1571 to convince the court of his plan to invade the Spanish Netherlands. He wanted to unite the French against the Hapsburgs, whom he saw as the real enemy. This plan greatly appealed to the young King Charles.

Coligny did not stay at court long, as the council did not support his plans. He returned to his estates. The Duke of Guise tried to reopen the investigation into his father's assassination, but the council voted against him.

From December 1571 to May 1572, Coligny was again away from court. Catherine de' Medici pushed him to accept the marriage between Navarre and Marguerite de Valois, which was a key part of the 1570 peace. Coligny was increasingly focused on building an alliance against Spain, hoping to include German princes and even the Ottoman Empire. French friendship with England in April 1572 seemed like a big step towards this goal. However, the royal council almost unanimously opposed his plans.

Assassination Attempt

Coligny returned to Paris for the marriage of Navarre and Marguerite de Valois. His attendance was important for showing peace between Catholics and Huguenots. After the wedding, Coligny stayed in Paris to discuss violations of the peace with the king.

On August 22, 1572, Coligny was shot in the street on his way back to his home. He was likely shot by a man named Maurevert from a house. However, because Coligny bent down to tie his shoe, the bullets only injured his hand and elbow. The attacker escaped.

No investigation into who was responsible was conducted at the time due to the events that followed. Historians have different ideas about who ordered the attack. Some believe Catherine de' Medici, fearing Coligny's influence over the king and his war plans, arranged it. Others argue the Guise family, seeking revenge for their father's death, were responsible.

The King sent his own doctor to treat Coligny and even visited him. Coligny demanded that the king investigate the shooting. The king promised to find those responsible. Senior Protestant nobles began to threaten revenge. Coligny, despite advice from his allies, chose to stay in the city.

The Massacre

Catholics feared Huguenot retaliation for the attack on Coligny. This fear was made worse by the 4,000 Huguenot troops stationed outside the city. On August 23, it was decided to pre-emptively assassinate the Huguenot leaders. This event became known as the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre.

The Guise family and others drew up lists of targets. Guise was to attack Coligny. In the early hours of August 24, Guise's men attacked Coligny's residence. Coligny told his household to escape over the roof. A man named Johann von Janowitz burst into his room. Coligny was then pushed from the window.

After Coligny fell into the courtyard, what happened next is debated. Some accounts say Guise ordered his head to be cut off and sent to Catherine. However, a Protestant eyewitness said Guise did not dismount his horse but left after confirming Coligny was dead. Over the next few hours, a general massacre began, spreading through Paris and then to other cities in France.

Coligny's papers were seized and burned by the queen mother. Among them, according to a writer named Brantôme, was a history of the civil war that was "very fair and well-written."

Marriages and Children

Gaspard de Coligny had children with his first wife, Charlotte de Laval (1530–1568):

- Louise, who first married Charles de Téligny and later William the Silent, Prince of Orange.

- François, who became Admiral of Guienne. His son, Gaspard de Coligny (1584–1646), became a Marshal of France.

- Charles (1564–1632), who was a Lieutenant General.

With his second wife, Jacqueline de Montbel d'Entremont (1541–1588), Gaspard had one daughter:

- Beatrice (born 1572), who became the Countess d'Entremont.

Legacy

Several places are named after Gaspard de Coligny:

- Coligny, South Africa

- Fort Coligny, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- Châtillon-Coligny, in France

- Coligny Plaza, Hilton Head Island

- Coligni (misspelled) Avenue, New Rochelle, New York

Family tree

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sources

- Jean du Bouchet, Preuves de l'histoire généalogique de l'illustre maison de Coligny (Paris, 1661)

- François Hotman, Vita Colinii (1575), translated as La vie de messire Gaspar de Colligny Admiral de France, (1643; facsimile edition prepared by Émile-V. Telle (Geneva: Droz) 1987).

- L. J. Delaborde, Gaspard de Coligny (1879–1882)

- Erich Marcks, Gaspard von Coligny, sein Leben und das Frankreich seiner Zeit (Stuttgart, 1892)

- H. Patry, "Coligny et la Papauté," in the Bulletin du protestantisme français (1902)

- Arthur Whiston Whitehead, Gaspard de Coligny, Admiral of France (1904)

- Charles Merki, L'Amiral de Coligny (1909).

- A Paris colloquy on Admiral de Coligny and his times in 1972 resulted in a volume of essays, Actes du colloque l'Amiral de Coligny et son temps (Paris) 1974.

See also

In Spanish: Gaspar de Coligny para niños

In Spanish: Gaspar de Coligny para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |